Venice 2018 College cinema: Landscapes, portraits

Friday | September 7, 2018 open printable version

open printable version

Press conference for Biennale College Cinema and VR.

DB here:

As happened last year, I was invited to participate in the Biennale College Cinema Panel. This was the seventh year of the program, which supports the making of low-budget feature films by young people. Proposals, numbering in the hundreds, are reviewed, and out of those several projects are developed in workshops. After development, three projects are chosen for funding, to the tune of 150,000 euros each. You can read details of the program here.

It’s remarkable how much these filmmakers manage to do on this budget. Both last year and this year, I was impressed by the ambition and panache displayed in the films. None of the directors or producers are novices; many have extensive experience in media. Still, to make a feature is a massive accomplishment, and the flair and professionalism on display in the trio of films was heartening.

I was lucky to join a team of pros. Under the direction of Peter Cowie and Savina Neirotti, our group included Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, Chris Vognar, and Stephanie Zacharek. Our task was, refreshingly, not to award prizes but simply to offer responses to the finished works. All these writers are steeped in modern and classic cinema, and they’re eager to share their experience with new talent.

One theme that emerged from our public session was the idea that all three films emphasized the slow revelation of character over rapid, audience-engaging plots. Very much in the tradition of European “art cinema,” they aim to entice us with intriguing, sometimes mysterious and contradictory individuals. We watch those individuals confront situations in which their personalities can be revealed or can undergo change. So the filmmaker’s problem becomes: How to create drama out of character?

Into the woods

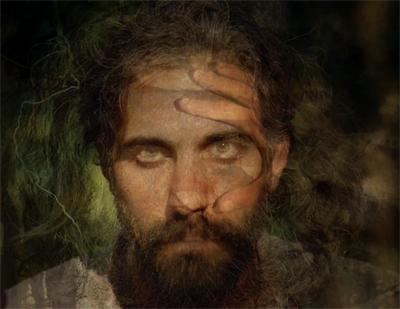

The most mythlike film was Yuva, by Emre Yeksan of Turkey. We’re plunged into a lush forest landscape, and in extreme long shot we glimpse a shaggy figure bearing a carcass (pig? dog?) into an opening guarded by fallen branches. Is it a shelter, or a passageway to another realm? Both, as it turns out.

Without the familiar signposts–no backstory, no titles identifying time or place–and confronting a wordless protagonist, we’re obliged to pay attention to details of what we see and hear. As in many character-centered films, dramatic buildup is replaced by details of daily routines. In this case, our protagonist Veysel explores the forest, finds a stricken bird he tries to revive, and–now traditional drama starts–spies uniformed guards on patrol.

Another film would have started by showing logging companies slashing their way through the forest, immediately establishing a conflict. Here, we’re given the guards, the whine of a woodchipper offscreen, the thrashing of helicopters above, and anonymous hands painting red X’s on trees to be felled. We have to conjure up a drama out of fragments. Even the closer shots tend to keep the landscape on our minds, not least in hallucinatory images.

As the film goes on, we see Veysel slapping mud over the red crosses while evading the patrols. We meet new characters: a stricken woman Veysel carries to the secret shelter, and his brother Hasan, who has come to take him away because the mysterious patrolmen say “they’ll kill you if you don’t leave.” So suspense eventually emerges, but always subordinate to the concrete spectacle of mysterious behavior on the part of our protagonist. The climactic revelation of where that burrow leads pushes the film to a more mystical level. Yuva‘s enigmas of characterization are in the service of broader themes about sanctuary and rebirth.

Born in a cemetery

If Yuva is a landscape-based film, Deva, by Hungarian director Petra Szöcs, is more of a portrait. True, the title refers to the town in Romania where the action occurs, but it concentrates on Kato, a teenager with albinism who is adjusting to life in an orphanage.

Again, character emerges from routines. On her “free day,” Kato shops and smokes and experiments with harsh makeup. She also surprises us. “I was born in a cemetery.” “I killed a boy because he mocked me.” We assume she’s displaying bravado, but either way she engages us as a person before any highly dramatic action is launched.

Still, a plot does develop, centering on Kato’s relationships with her caregivers, infused by her belief in her magical powers. When the attractive and sympathetic Bogi joins the orphanage staff, Kato is drawn to her, and Bogi befriends her–to the point of allowing an indiscretion that will jeopardize their relationship and Bogi’s job. Kato also helps mastermind a piece of mischief that will discredit Anna, a less popular teacher.

Yuva favors distant shots and long takes, but in Deva, Szöcs relies on tight framings and layers of depth (often out of focus) to fragment her scenes. Faces and dialogue are often kept offscreen, the better to concentrate on Kato’s fascinating face and gestures.

Deva‘s laconic style itself becomes a source of curiosity for us, as bits of connective tissue are left out and we’re obliged to appraise the changes in Kato’s character. Our curiosity is enhanced by the performance of Csengelle Nagy as Kato, which is riveting in its sobriety and contrasts with the warm and extroverted Boglárka Komán in the role of Bogi. Again, narrative engagement emerges from the mysteries of personality rather than the pressures of an external situation.

On ice

I know it sounds too neat, but to some extent the landscape and portrait impulses find a balance in Zen in the Ice Rift, directed by Margherita Ferri. The action takes place in the majestic, somewhat menacing Italian Apennines, where Maia, nicknamed Zen, lives with her mother. As the only girl on the ice hockey team, Zen is mocked as a lesbian, and she has become hardened to the bullying she encounters. With her butch-flip hairdo and perpetual frown, she has a hair-trigger temper and all but begs people to fight with her.

One screenplay stratagem for gaining audience sympathy is to have your protagonist treated unfairly. This happens early on, when Zen is slammed by a player on the ice. She reacts by firing a BB pistoal at her loitering teammates. They get payback by locking her neck to a railing. Voilà: a sympathetic but imperfect protagonist, someone we can watch with keen interest as she must make decisions, bad or good.

Those decisions include accepting overtures of intimacy from Vanessa, the prototype of the beautiful, popular teenager. Zen’s sexual identity, confused from the outset, becomes the focus of the drama. This process develops in unexpected directions and leads to a climax that exhibits how teenagers’ use of social media can take bullying to a brutal level.

When Zen’s coach tells her at the beginning that she had a chance to try out for the national woman’s hockey team, I briefly thought we were going to get a sports film, in which the protagonist undergoes the rigors of training and the test of competition. No such thing. The focus is on Zen’s place in the world of teenagers. Her hockey talent is one part of her personality, not the source of goals and conflicts and ultimate triumphs, let alone “life lessons.”

Yet the sports element isn’t gratuitous. Ice becomes a metaphor in the course of the film, as insert shots show glaciers cracking while Zen is forced to confront her still-developing identity. At the end, when she takes to the rink in a burst of solitary confidence, we realize that her defiance hasn’t diminished. Zen in the Ice Rift shows how the drama of character can unfold in both a social setting and the larger milieu.

In addition to the feature films at the Biennale College, there were four Virtual Reality projects associated with the program. The three I saw explored aspects of VR as a medium: awkward intimacy in Metro Veinte, the sense of sinister enclosure in Elegy (aka VRtigo), and the possibility of sampling an eerie landscape in Flood Plain, which extends the narrative situation and imagery of Yuva. At the same time, I thought that they would have made interesting films–which probably indicates that I see rather close affinities between VR and cinema.

Major differences, of course, include VR’s absence of a frame and the possibility of self-willed exploration. As members of our panel suggested, VR creators will need to find ways to motivate the presence of an onlooker in the virtual space, and, if storytelling is the goal of a project, to guide the viewer to salient elements. Narrative, we’ve known since forever, depends on controlling attention.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale. Thanks also to my colleagues on the panel for lively movie talk throughout our stay.

Last year’s College visit is discussed here, and my earlier journey into VR here.

Make the world go away: Venice Biennale VR theatre at Lazzaretto Vecchio.