Venice 2018: The Middle East

Monday | September 10, 2018 open printable version

open printable version

As I Lay Dying (2018)

Kristin here:

As Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli pointed out earlier this week, Arab cinema is well represented here at the Venice International Film Festival. The same is true of Middle Eastern films in general. I couldn’t catch all them, but here are some thoughts on those I saw.

The Palestine question as sit-com

Comedies about ethnic hostility in Ramallah are understandably rare. For a long time the only one I knew of was Elia Sulieman’s masterly Divine Intervention (2002), though there may be others. Now we have Sameh Zoabi’s Tel Aviv on Fire, a real crowd-pleaser playing in the competitive Horizons section of the festival, a section designed to showcase promising early-career filmmakers.

Despite the title, which might suggest a grim tale of conflict, perhaps involving terrorism, the film is very funny. “Tel Aviv Is Burning” is the name of a daily melodramatic TV series made in Ramallah by a group of Palestinians but enjoyedby both Jewish Israelis and Palestinians–mostly women. (All citizens of Israel are considered Israeli. This means that, ironically, the Israeli Film Fund is required to provide funding to Palestinian projects; it is one of Tel Aviv on Fire’s backers.) The story arc is at a point where a Palestinian woman is assigned to disguise herself as Jewish in order to seduce an important Israeli general and get a key to a hiding place for military plans.

Salam, the protagonist (played by Kais Nashif, who won the best actor award in the Horizons competition), is the lowly nephew of the show’s producer, fetching coffee and helping keep the Hebrew dialogue authentic. Suggesting a bit of action one day, he is promoted to be a writer, despite having no experience or skill. When Saam is stopped for no reason at an Israeli checkpoint (above), he meets a general, Assi. Salam boasts about being a writer on the show, which happens to be a favorite of Assi’s wife. Hoping to impressive his shrewish spouse, Assi puts pressure on Salam to slant the story: the heroine should fall in love with and marry the Israeli general she has seduced. Eager to get away, Salam agrees.

The rest of the story is a cleverly scripted series of twists as Assi makes further demands to make the Israeli general more sympathetic and Salam tries to foist these on his reluctant collaborators. One might argue that the final surprise revelation does in fact make the film lean toward the Israeli side. On the whole, though, Zoabi’s film balances the two factions and manages to convey that the ongoing conflict is absurd, given the many similarities between the two main characters and the universal appeal of “Tel Aviv on Fire” across Israel’s population.

One strength of the film is the stylistic contrast between the main story’s conventional lighting and location shooting and the tacky sets, garish colors, improbable dialogue, and over-the-top performances in the scenes from the TV series.

A microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Veteran Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai contributed a program of two films to the festival. The first was a short, A Letter to a Friend in Gaza, the second the feature A Tramway in Jerusalem, both playing Out of Competition.

A Letter to a Friend in Gaza is a evocation of the bitter disagreement between people, even within families, using a text by Albert Camus to sum up the issues in poetic form. I suspect one would need to know a great deal about the Palestinian occupation to fully grasp this oblique work.

The issues are readily apparent, however, in A Tramway in Jerusalem. Set aboard a tram, with occasional shots on platforms where it stops, the action consists of a series of short scenes between a wide variety of citizens. The episodes are separated by titles announcing the time of day, but these skip about, suggesting that this is not a day-in-the-life-of a tram tale but a series of random encounters. The vignettes are not connected, though a few characters recur, most notably a French tourist introducing his beloved Jerusalem to his son. The participants in these short scenes are played by actors, though the only one likely to be recognizable to a broad audience is Mathieu Amalric as the tourist (above).

The scenes suggest a range of possibilities for successful or failed coexistence. For no reason but prejudice a woman accuses a Palestinian man standing next to her of sexual harrassment, and the guards on board immediately throw him to the floor. Two sophisticated young women, one Palestinian with a Dutch passport, the other an Israeli, are standing side by side. They chat casually, clearly very much alike, and when, again for no reason, an aggressive guard demands the Palestian’s passport, the Israeli stands up for her. In an overly long episode, a Catholic priest soliloquizes about the death of the three religions struggling for dominance in their mutually sacred city. The French tourist, determined to idealize Jerusalem, fails to realize that a local couple is poking fun at him by enthusiastically advocating the violent suppression of Palestinians.

The Iranian search narrative endures

Not all Iranian films involve searches by any means, and yet searches, whether they involve a journey or not, provide the structure of many familiar classics like Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Mirror. By chance, two films at this year’s festival show searches involving in one the beginning of life and in the other its end.

Mostafa Sayari’s first feature, As I Lay Dying (Hamchenan ke Mimordam), also played in the Horizons competition. It begins after the death of an old man. One of his sons, Majid, who has cared for him recently, admits to the doctor that he had provided the sleeping pills that apparently killed his father, but the doctor agrees not to mention this on the death certificate. A hint that the time of death is not known provides the first clue in a subtle mystery. Further clues surface in the course of a psychological drama among the four siblings who assemble to drive their father’s body to a small, distant village for burial.

As the journey continues and quarrels develop, the siblings question Majid as to why he chose this remote village for the burial. The length of time that the father has been dead emerges further as a significant factor. By the end, the answers to the three siblings’ questions becomes apparent to them.

Speaking with others who had seen the film, I heard complaints that the story was difficult to understand. I think that As I Lay Dying is something of a mystery story, without being strongly signaled as such, and that sufficient clues are dropped along the way that the viewer should be able to understand the situation by the time the story ends, rather abruptly and perhaps seeming not to offer a resolution. (It would help to know that Muslim burials are supposed to take place as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours.) Certainly nothing is made explicit at the end, though again, an attentive viewer should figure out the implied outcome.

The film takes place largely on a bleak desert road, including some beautiful widescreen compositions reminiscent of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, perhaps coincidentally also involving a search in the desert, in that case for an already buried body. (See top.)

The search narrative goes back at least as early as Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht O Ayeneh, made 1963-64, released 1966). It was one of the historically important films shown in the “Venice Classics” series of recent restorations.

Brick and Mirror is generally considered the first Iranian art film, having come out three years before Dariush Mehrjui’s classic, The Cow (1969). Golestan was an experienced filmmaker, mostly of documentaries, but Brick and Mirror was his first fiction feature.

The title has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film but is more evocative, being, as Golestan has revealed, derived from a Thirteenth Century Persian poem: “What the Youth sees in the mirror, the Aged sees in the raw brick.” The word “brick” here does not refer to the familiar fired brick, which costs money to buy, but to the simple mud brick, widely used by the poor across the Middle East, since anyone with access to silt and a simple wooden frame can make them.

The story begins one night as the taxi-driver protagonist, Hashem, discovers that a woman passenger has left a baby in the back seat of his car. In a famous scene, he wanders the desolate neighborhood searching for her (see below). Eventually his girlfriend joins him in his apartment to help care for the child. The experience leads her to hope that they can marry and raise the child themselves, turning their so-far aimless affair into a family. The quest to find a practical, humane way to dispose of the baby–or not–takes up the rest of the film. Near the end, a lengthy scene of babies and young children in an orphanage reflects Golestan’s documentary experience.

The new print recalls the rough, often dark look of black-and-white widescreen films of the 1960s, especially those of the French New Wave. Golestan’s story of fruitless wandering and unresolved relationships has been compared by some critics to the films of Antonioni, and it seems clear that Antonioni’s work and other European films of the 1950s and 1960s influenced him. There are, however, distinct differences. While Antonioni deals with the psychology of bourgeois characters (except in Il Grido), the couple in Brick and Mirror are working-class, and their problems are caused as much by their social situation as by any general ennui.

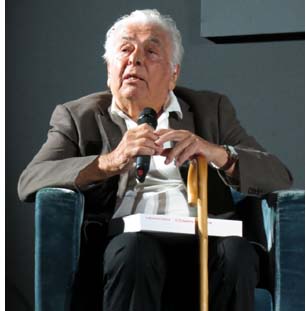

Remarkably, Golestan was present to introduce the film. At 97, he remains articulate and charming. He primarily sketched out his early career and the inspirations for Brick and Mirror. The most interesting point concerned a startling moment during the early scene of Hashem searching the dark neighborhood for the elusive mother of the baby. A close composition of him at the top of a long stairway suddenly leads to a quick series of axial cuts, each shifting further back until he is seen in extreme long shot. The moment reveals the empty staircase and emphasizes the hopelessness of the chase. Golestan emphasized jump-cut quality of the passage and mentioned that he had not seen Breathless at the time Perhaps the moment harks back further, to the axial cuts of static figures used in Soviet films of the 1920s and the work of Kurosawa.

Previously only incomplete, worn prints of Brick and Mirror were available, and then only in rare screenings. The importance of this restoration was emphasized by the festival’s publication of a short book, Brick and Mirror, which brings together a number of essays by Golestan and others. It also describes the restoration, done with the director’s cooperation and accomplished at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in Bologna. My thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with a copy and more generally for his important work in reviving Iran’s film heritage, including programing the Iranian season at Bologna that I reported on in 2015.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more photos from this years Mostra, see our Instagram page.

[September 12: Thanks to Steve Elsworth for some corrections.]

Brick and Mirror (1966).