On the Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters

Tuesday | September 25, 2018 open printable version

open printable version

Often this scandalous or honorable story, this beautiful or ugly one, will be told you the next day or the next month, sometimes in fragments. There is nothing that is of a piece in this world, everything is a mosaic.

Balzac, Une fille d’Ève

DB here:

We’re not big fans of listicles. Our only effort in this direction is our annual review of the 10 best movies of 90 years ago. But now we have my Criterion Channel installment devoted to Hiroshima mon amour. (There’s a sample here.) The installment is focused on the film’s use of editing. That topic does allow me to touch on wider matters of storytelling and theme, but I found myself struggling to squeeze in all I wanted to say. So. . . .

If you haven’t seen the film, both this and the Criterion Channel segment will teem with spoilers. Now I’ll give a plot synopsis, but the shocks in the film’s early stretches are probably softened if you know the story’s premises. So if you haven’t seen the film yet, you’re advised to stop reading now.

Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 feature film directed by documentarist Alain Resnais, tells the story of a brief sexual affair between an unnamed man and woman. She has come to Hiroshima to make a film about the effects of the US nuclear bombing of the city in 1945. Her plane is scheduled to leave the following day, but he asks her to stay longer in Japan. As a result, what drama there is becomes psychological—pressured by her deadline, but complicated by her memories.

After their first night of lovemaking, she tries to break with him, but in the course of the day he pursues her and they meet at intervals. They go to his house for another bout of lovemaking, to a bar called the Tea Room, to the train station, and back to her hotel, where the film began. In the course of their affair, she recalls and recounts her wartime romance with a German soldier stationed in her city of Nevers. At the liberation, he was shot by a sniper. The townsfolk punished her by cropping her hair and confining her in a cellar.

In a gesture characteristic of ambitious cinema of the period, we don’t definitely learn that the woman decides to leave. The final scene, suggesting that she will always think of the man as Hiroshima, does imply that they’re parting. More important, in the course of their affair she has realized that her memories of her first love are fading, and she fears that makes her deeply disloyal to him. Worse, she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

Hiroshima is one of the most important films ever made, summing up many tendencies of modern cinema but also indicating new directions for later filmmakers. Its implications and possibilities radiate out in several directions, like the spidery silhouette (in negative?) under the opening credits. So a listicle format seems, for once, justified.

(1) The opening

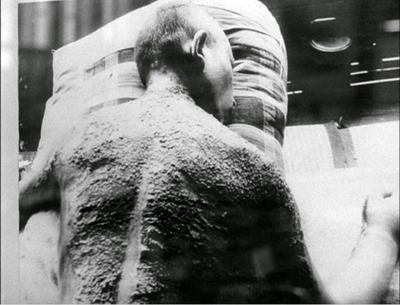

Two bodies, from the waist up, are locked in an embrace. The faces aren’t visible. At first, the bodies are powdered with dust but as the images dissolve into one another, the limbs are glittering and then oily with sweat.

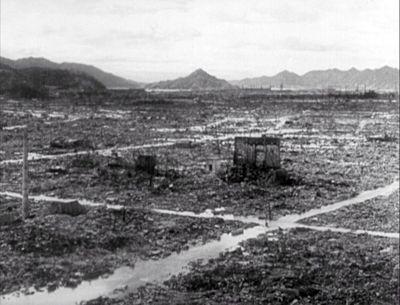

These images give way to documentary-style shots of Hiroshima, both in the present and in newsreel footage. We see modern architecture, a hospital, museum exhibits, city streets, a cheerful lady bus conductor, victims of the nuclear blast, and even restaged scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, taken from fiction films.

Over all the footage float a male voice and a female voice: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima–nothing.” “I saw it all…” She describes what can be seen and understood, while he contradicts her. We return intermittently to their bodies. The sequence concludes with her voice: “I met you here.”

Thus ends one of the most daring sequences in film history, a dense thirteen minutes of imagery, music, and dialogue. I think it’s hard for us today to grasp just how jolting this opening felt in 1959. Ten years after its premiere, when I first saw it (and without much foreknowledge), I was overwhelmed. For me, and I think for many others, cinema wasn’t quite the same after this.

For one thing, there’s the sex. Although it’s portrayed abstractly, the voluptuous skin tones and clutching, twisting arms are powerfully erotic–and poetic. The oily skin might be considered realistic, but the dust particles can’t be justified as anything but metaphorical, perhaps nuclear fallout or the ashes of a city in flames. (Is this like the embracing couples discovered in Pompeii by the heroine of Voyage to Italy?) Later the sexual angle will become more socially specified; it’s an “interracial” coupling, involving a French woman with a Japanese man. An entire “social problem” movie could be made about this situation, which this film takes utterly for granted.

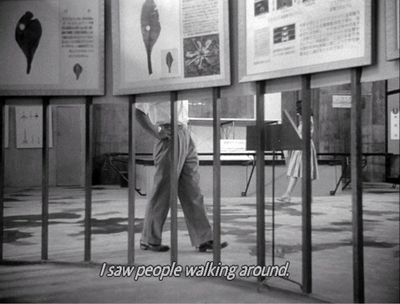

Then there’s the juxtaposition of this stylized intercourse with the bombing of Hiroshima–and naked bodies very different from the ones we see in bed. We’re given smooth tracking shots through a hospital and a museum. In some of his documentaries Resnais had presented locales in solemn, slightly disquieting traveling shots, mimicking a tourist-eye view into a library (Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956) or a concentration camp (Nuit et brouillard/ Night and Fog, 1956). Here, similar traveling shots are more or less anchored to the unseen woman reporting on her impressions.

I say more or less because, in a slippage characteristic of the film, sometimes the camera height is lower than an adult’s eye level, as in the second shot above. And often the camera is withdrawing along the line of the museum exhibits, as if looking backward.

Already the imagery is rendered a little detached from a human perspective. More generally, by suppressing the woman’s face and eliminating diegetic sound, the shots for all their concreteness seem unreal, as if pulled up from memory or imagination.

When the shots segue to found footage (“I saw the newsreels”) and then to strident reenactments, those too seem less historical records or blatant fictionalizing than part of a phantasmagoric vision.

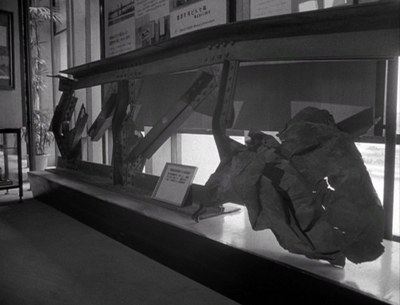

Maps and twisted relics, faces and stones, kitsch and authentic suffering are all put on the same plane, with a disturbing neutrality.

Perhaps this is the tragedy of Hiroshima as absorbed by a consciousness unequal to it. But what consciousness could comprehend it? Night and Fog openly proposed that our minds couldn’t grasp the enormity of the Holocaust. Not that this was a counsel of despair; our very helplessness was a warning to remain vigilant against the next glimpse we might get of human monstrousness. Here another voice challenges the limits of our sympathetic imagination: “You saw nothing.”

What about the opening’s soundtrack? Plaintive piano music, Debussy-ish, passes to strings and woodwinds–slow and brooding, but sometimes disarmingly bouncy. Nothing could be farther from the Mahleresque scores of Hollywood cinema or most documentaries than this chamber-music intimacy. The score pulls a bit away from the images, we might say, seldom emphasizing them even at their most horrific.

In his documentaries, Resnais had pioneered a lyrical, somewhat dry voice-over quite different from the conventional nudging or hectoring Voice-of-God commentary. Like the tracking shots, though, this vocal technique takes on a new effect in a fictional cinema. For one thing, when and where is the conversation occurring? Not evidently during the lovemaking. Before? After? Maybe never? Is it a sort of telepathic exchange, expressing the essence of her tourist-level days in the city and then his assured sense that such an experience blinded her to the real Hiroshima? Interestingly, we’ll learn that he wasn’t in Hiroshima during the attack. So perhaps he, like the narrator of Night and Fog, is warning her against premature confidence in understanding any historical event on this scale.

The woman’s voice dominates the soundtrack, meditating on her lover and her surroundings. Again, it might be a monologue addressed to the man at some point, but thanks to rushing shots through Hiroshima streets, it equates his body with his city. This motif will culminate at the climax, when she compresses her memories of 1944 down to landscapes in Nevers and she decides to give her lover a name: Hiroshima.

Since the mid-1940s, André Bazin had argued that the future lay with long take-filming that respected the continuum of reality–the continuum that Soviet filmmakers had freely splintered in order to make rhetorical and poetic points. Yet with this overture, Hiroshima revived and revamped the Soviet tradition of montage-based moviemaking. The sequence averages a little more than six seconds per shot, a rate seldom seen in European fictional film of the 1950s. The result somewhat recalls the free editing of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but it anchors the visual disjunctions in psychology and a personal drama yet to be specified.

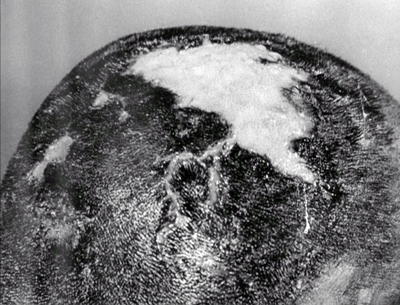

Bazin had worried that by chopping the world into little fragments, editing by its nature ruled out ambiguity of expression. Yet here was a film that showed, as avant-garde filmmakers had done, that montage could generate poetic ambiguity. Editing patterns could create analogies and associations. The spatter on a rock could evoke the scars on a victim’s head, and the dusted couple of the opening could become ghostly doubles of a victim of radiation.

One could even intercut staged footage and documentary material without hiding the filmmaker’s artifice (as Citizen Kane does with the faked footage in “News on the March”). Free montage and collage-like mixing of documentary and fiction would be hallmarks of 1960s and 1970s films by Alexander Kluge, Dušan Makavejev, and of course Jean-Luc Godard.

Something similar happened with the soundtrack. Detached, unemphatic scores would become part of the repertoire of modern cinema, as would floating voice-overs. Films like Chungking Express and Wings of Desire, to say nothing of the work of (again) Godard, would show the expressive power of voices cut free from story time and space. Montage, as Eisenstein prophesied juxtaposed not only image to image but image to sound.

No later passage of Hiroshima mon amour is as aggressively disorienting as this overture. It’s as if Psycho started with the shower sequence. This opening not only introduces a lot of cinematic and thematic material. It also seeks to sensitize us to images and sounds, as a poem at the start of a novel might sensitize us to language. My discussion of editing in the Criterion installment points out that most of the ensuing film is cut in a pretty orthodox way, respecting the rules of continuity construction. But the sheer disjunctiveness of this prologue prepares us to notice whatever abruptness and juxtapositions do arrive. Assailed by this opening, at once jagged and eerily smooth, we’re set to register some even finer-grained shifts in time and sequence to come.

(2) Flashbacks that aren’t flashbacks

Hiroshima’s script by Marguerite Duras was, Resnais claimed, based on “parallel editing” that would link wartime France and contemporary Japan. But Resnais insisted that this editing didn’t create flashbacks.

Here is another movie, one that Resnais and Duras didn’t make. A French woman visiting Hiroshima on a film shoot turns tourist. She then meets a Japanese man and they have sex. Next day she avoids him, but he pursues her and eventually she agrees to spend the evening with him. In a bar we get the big reveal: the woman explains her wartime love affair and the punishment that drove her out of Nevers. Her past episodes are given in large blocks, perhaps one long flashback. The plot concludes with the man and the woman forced to choose their future.

We’ve already seen that the woman’s tourist-eye view has been fragmented, scrambled, and stylized in the opening montage. We might be tempted to call those images flashbacks, were they not so firmly part of an overall collage including purely documentary material. But once the story proper begins, we, or at least I, am inclined to call the bursts of images from 1944 Nevers flashbacks–brief ones, but flashbacks.

I say this because I take the primary purpose of a flashback is to present story material out of chronological order. A secondary purpose, not always in force, is to represent a character’s memories. Some films, especially after Pulp Fiction, rearrange story order without appeal to character memory. In classical studio cinema, though, flashbacks are usually motivated by a character recalling or recounting an event that she remembers. More often than not the scenes we see in the past aren’t restricted to what she witnesses or even knows about. Memory provides a rationale for the main purpose–revealing action in the past.

But there’s a contrary line of thought that says that a character’s memory ought not to count as a flashback because memories exist in the present. Arthur Miller took this line with respect to the time-shifts in his play Death of a Salesman, as I discuss in Reinventing Hollywood. Resnais, it turns out, felt the same way. For him, the fragments of the past that interrupt the present-time scenes of Hiroshima exist in the present because they’re being remembered. He wrote to Duras during shooting: “The past won’t be expressed by true flashbacks, but will be felt to be present throughout.” In 1968 he reiterated: “In Hiroshima there is not a second’s worth of flashbacks.”

There’s no point in quibbling about terms, but we should note that Resnais thought his interruptive images of the past were capturing something important about how memory works. Memory is fragmentary and jumbled, not operating in the big chronological blocks given us in 1940s Hollywood flashbacks. When asked by his producer if Citizen Kane hadn’t already shifted chronology, Resnais replied: “Yes, but with me, it’s all disordered.”

Moreover, memory is abrupt and fragmentary: Resnais uses cuts, not dissolves, to deliver his memory images. The first instance in the film has become a locus classicus. The woman sees her Japanese lover’s hand twitch, and that leads to another hand, a quick pan to a dead man being kissed, and then the Japanese lover again. This time-shift is literally a flash, lasting only a few frames.

And to insist that memory operates in the present moment, Resnais uses present-time diegetic noise–a train whistle in the scene above, a pop tune on a jukebox later–providing something that literature can’t: the absolutely simultaneous presence of now and then.

Again, Resnais brings into sound cinema narrative strategies that had emerged in silent film. Gance in La Roue, Fredrikh Ermler in Fragments of an Empire, and others had provided rapid-fire memory montages. In most commercial sound cinema, this sort of mental imagery was largely confined to one-off sequences depicting dreams, hallucinations, or mental illness. Resnais and Duras boldly made an entire film in which recollected moments unexpectedly erupt into present-tense action.

Again, though, the filmmakers introduce ambiguity. It’s hard to plausibly assign some of the “memories” of Nevers to the female protagonist. Bare landscapes and abrupt tracking shots of empty streets seem more like Eliot’s “objective correlative,” more oblique representations of feelings, than traces of what the woman has witnessed. Even the invasive images from the past aren’t free of the uncertainties that hover over the opening sequence. This strategy of hovering between subjectivity and “authorial commentary” would become central to 1960s art cinema–perhaps most obviously in Red Desert, where the unrealistic color can be taken as both an expression of the protagonist’s alienation or a more detached, stylized presentation of a modern wasteland.

(3) Talkies and walkies

Griping about Antonioni’s longueurs, Dwight Macdonald remarked that “the talkies have become the walkies.” His complaint captures something important. From Bicycle Thieves through La Strada and L’Avventura up to Linklater’s Before/After trilogy, the idea of building a plot around two characters’ more or less mundane traipsing became a salient option for filmmakers who wanted to stray from classical narrative organization.

But settling down in one place to talk became important too. Serious European cinema often featured dialogue scenes of a length that would have been discouraged in American cinema. Play adaptations like Sjöberg’s Miss Julie (1951) naturally featured such protracted conversations, but so did works by Bergman such as Waiting Women (1952), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Brink of Life (1958). Having revived silent-film montage in Hiroshima‘s early stretches, Resnais and Duras makes peace with their contemporaries in the second part by settling their characters down for two good chats broken by a long stroll.

It all starts when the man declares, after a second bout of lovemaking, that they have sixteen hours to kill before her departure. By Hollywood standards, this period should be handled with dramatic crises leading to the deadline. Instead, we get a quick montage of the city at dusk (with figures unnaturally still, as if rehearsing for walk-on parts in Last Year at Marienbad) and the two of them at a table in the Tea Room bar.

It’s in this lengthy scene that the woman’s memories become most coherent for us and the man. What was private in earlier parts of the film–flashes like the hand on the bed–become externalized in her confession. Again, though, we get Resnais’s version of “disorder.” For one thing, her Nevers story isn’t given in a block, but rather as a burst of fragments. After their second lovemaking, she had already begun to tell her lover about her affair with the German, and the editing was rather choppy: six alternations of past and present in about seven minutes. Now at the Tea Room she’s more explicit about his fate and her punishment. Over twenty-four minutes, the action alternates between Hiroshima and Nevers seventeen times. Often a single shot breaks into her confession.

For another thing, the incidents remembered tumble out of order. Glimpses of her imprisoned in a basement are followed by her ritual haircutting before being sent there. Image and sound fall out of true: we see her pedaling to Paris, we hear her telling us what she read in the newspapers upon arriving. We need to integrate what she’s recounting now with what she’s recalled earlier.

By the time the couple leave the Tea Room, we have a fairly coherent account of the woman’s Nevers trauma. In our alternative film, we’d now have a climax in which she decides to leave Hiroshima or stay. Instead, she and the man separate. She returns to her hotel, washes her face, accuses herself of betraying her German lover with the Japanese, and. . . wanders back outside.

She returns to the Tea Room, now closed. The plot’s irresolution is prolonged. Her lover materializes, as if summoned by her voice-over. The woman, now distraught, tells him she’ll stay. Immediately she tells him to leave. He says he could never leave her. Then he leaves her.

What follows is a string of further evasions and encounters, almost a suite of variations on how a couple can seek to connect and avoid connecting. The film becomes a walkie. Resnais planned the street scenes, he explained in a letter to Duras, by listening to a tape of her reading the commentary and blocking the actors’ movements with wooden dolls.

The woman moves down the street, trailed by her lover. He follows her to a train station, and then to a bar called–you must remember this–Casablanca. She eludes him by letting a slick stranger join her for a drink. The night goes on. Dawn arrives.

In the course of these stop-and-start ramblings, memories return, but images of her lover dwindle, to be replaced by those of Nevers; he has faded into the landscape. As I indicated, these might as well be narrational commentary rather than her memories, with the film’s overarching form juxtaposing the French city with the Japanese one in ways she doesn’t yet grasp.

Now you know why people say art movies seem never to end: They tease us with closure and then deny it. Extended talk scenes and walk scenes, however realistic they may seem in contrast with busy Hollywood plots, are also conventions of this mode of filmmaking. It’s up to the filmmakers to shape them to their immediate purposes.

(4) At the limit

In a plot centered on action–goals, blockages, clashes among characters, struggles to accomplish some feat–you typically have a clear-cut climax and resolution. The protagonist either succeeds or fails. But when you deny that sort of arc, you have to find other ways to inject drama. In Hiroshima, we have a classic instance of the undecided protagonist, who can’t settle on a goal and so drifts from situation to situation, each one of which dramatizes a facet of her character, or of her indecision.

Sooner or later, the plot has to stop, so if there’s no decisive way to end the action, how do you conclude? The most favored option, borrowed from serious literature, involves what literary theorist Horst Ruthrof calls a “boundary situation.” Instead of creating a resolution by what the protagonist accomplishes, the plot confronts the character with something that forces a reevaluation of his or her life. The drama is psychological, not physical; the resolution involves insight, not action of the normal sort. As Ruthrof puts it, the character “in a flash of insight become[s] aware of meaningful as against meaningless existence.” The boundary situation is existential, consisting of “a final vision or revelation, rejection of false moral premises, and the gain of a state of authenticity.”

James Joyce called such bursts of recognition “epiphanies,” and he employed them in his Dubliners short stories. Ruthrof argues persuasively that they can be found throughout modern European literature, from Flaubert and Tolstoy to Conrad and Thomas Mann. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I proposed that many films in the European tradition had recourse to boundary-situation plots. Guido’s acceptance of all the contradictions of his life in 8 ½ and Isak Borg’s reconciliation with his past in Wild Strawberries are fairly clear examples.

Instances of boundary situations are central to two Marguerite Duras novels of the period. The Square (1955) consists of routine encounters on a park bench between an unnamed man and woman. They talk at length each time, and the climax comes when the man declares suddenly, “I’m a coward.” Moderato Cantabile (1956) is set in a cafe, and the conversations are broken by time shifts to piano lessons and a party. Again we get laconic exchanges between a man and woman who don’t know each other, culminating in confession and tears. (“I wish you were dead.”/ “I am.”) Resnais said that he wanted to work with Duras after reading Moderato Cantabile.

In Hiroshima, what, finally, provides closure for the plot? Not the woman’s decision to stay or not; we never know what she chooses. Instead, her affair has forced her to psychological crisis. She realizes that her memories of her first love are partial and impermanent. This shocks her as an act of disloyalty. And she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

The film’s climax is a personal epiphany, not a clear-cut showdown. The woman has come to accept that her past and present are ephemeral, that even the memories she’s making now–of the lover whose skin she adores–will wane. What remains? The late sequences that take her wandering through his city cement the relation between his body and the town: her voice-over repeats the exultant incantation that opened the film, but now we hear it over shots of neon signs and empty streets. So she can name the man: “Hiroshima.” And although we have never had privileged access to his mind, the fact that he rejoiced in hearing her story of her past, in being the only person she had told of it, he may well have achieved a similar epiphany. He reciprocates, calling her “Nevers. Nevers in France.”

This is of course just one interpretation. Whatever thematic implications a critic constructs from the film, though, I think that those will depend on acknowledging the transformative boundary situation that functions as a climax. The woman’s confrontation with the man and the city has forced her to a self-recognition, putting her life in a new light.

Cinema of character rather than plot, we sometimes call it. I’d rather say it’s a particular breed of plot, one that replaces achievement of external goals with achievement of partial, tentative, but still life-transforming insight. A different dramaturgy for a different tradition.

(5) Consolidating innovations

Voyage to Italy; La Pointe Courte.

Hiroshima mon amour changed the way movies told their stories, not least because it revised some trends that had emerged in two other European films of the 1950s.

One was Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (released late 1954). Despite featuring two major American stars, Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders, it was far from an ordinary Hollywood picture. It pushed further that conception of “plotless,” anecdotal narrative on display in Neorealist films like Paisá and Umberto D. The center of the tale is a couple whose marriage is quietly dying. Having inherited a villa in Naples, the characters must decide to sell it. But instead of building a conflict out of this goal, the film fills itself with episodes of the husband’s philandering and the wife’s touring of the region. It settles its plot by an epiphany in which man and wife are mysteriously reconciled.

Voyage to Italy, wrote Jacques Rivette, “opens a breach. . . . All cinema, on pain of death, must pass through it.” “The story is loose, free, full of breaks,” said Eric Rohmer, “and yet nothing could be further from the amateur. I confess my incapacity to define adequately the merits of a style so new that it defies all definition.” Rivette again: “Here is our cinema, those of us who in our turn are preparing to make films (did I tell you, it may be soon).”

The Cahiers du cinéma critics weren’t so eager to welcome Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1956). A married couple drifts through a fishing village, and their meditations on their life together are woven into documentary recording of the locals’ work and relaxation. André Bazin championed the film, but others in the Cahiers team were cool, objecting to the stylized photography and performances. The fact that it was made by a woman probably didn’t help. Against Varda’s wishes Cahiers ran a photo of her as a martyred angel, and it’s hard not to see it as mockery, especially since the caption revels in Henri Agel’s “wicked manhandling” of the film in his review.

Because La Pointe Courte was produced by a company registered to make only short films, it couldn’t achieve commercial distribution and so circulated mostly to ciné-clubs. But most reviews were praising, and today it’s recognized as a bold anticipation of the Nouvelle Vague.

Among those films that La Pointe Courte anticipates is Hiroshima. Resnais, was editor on La Pointe Courte. He initially resisted the job, telling Varda: “Your explorations are too close to mine,” but he wound up working for free.

Three films about couples, then, rendered in a strikingly episodic way. All use long walks and extended talks. All three display a dual structure as well. Rossellini intercuts the activities of husband and wife. Varda, influenced by the parallel structure of Faulkner’s novel Wild Palms, alternates scenes of village life with the couple’s wanderings. And as we’ve seen, Resnais asked Varda to build Hiroshima upon an editing strategy that set the past against the present.

There are probably other antecedents of the film (Resnais was reminded of Il Grido when cutting La Pointe Courte), but I hope I’ve said enough to indicate how Resnais recasts an emerging tradition of ambitious European cinema. He goes beyond it in all the ways I’ve mentioned and more I haven’t, but like all art works it owes part of its power to its reworking of techniques it inherits.

We could list more reasons that this film endures, certainly. Not least: Its unforgettably enigmatic title. Even that offers us ambiguous fragments, in something like an abrupt cut. “Hiroshima mon amour” might suggest “I love the city of Hiroshima.” But there’s no punctuation, no comma or dash that would equate the two terms. Instead, we might take it as a splice. It might be a contrast: “Hiroshima” versus “my love, the German soldier.” But then, since the Japanese comes to stand in for the German, the title would equate “Hiroshima” to him. This would be consistent with the final dialogue: “Hiroshima, that’s your name.” The film’s very title implies the ambivalent juxtapositions that Resnais will build up through cutting.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson and to Kelley Conway for discussion of Resnais and Varda. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

Bazin’s worries that montage lacked ambiguity are set forth in various essays in What Is Cinema? vol. I, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (University of California Press, 1967), particularly “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” 36.

Resnais’s comments about Hiroshima‘s avoidance of flashbacks are quoted in Jean-Louis Leutrat, Hiroshima mon amour, 2nd ed. (Armand Colin, 2006), p. 84. He describes his film’s “disorder” in conversation with Anatole Dauman, quoted in Jacques Gerber, Souvenir-Écran: Anatole Dauman, Argos Films (Pompidou, 1989), 86-87. He mentions his use of puppets to plan his staging in a letter reprinted in Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima, ed. Marie-Christine de Navacelle (Gallimard, 2009), 66. This lovely edition shouldn’t be confused with Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima!, ed. Raymond Ravar (Brussels: Institut de Sociologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1962). This remarkable volume is a detailed book-length analysis of the film and includes interviews with Resnais.

Horst Ruthrof’s discussion of boundary situations appears in The Reader’s Construction of Narrative (Routledge, 1981), 101-108.

See Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 192-208, for Rivette and Rohmer on Voyage to Italy. The macho mockery of Varda occurs in Cahiers no. 56 (February 1956), 29. For a comprehensive discussion of La Pointe Courte, see Kelley Conway, Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press, 2015), 9-26. We consider Kelley’s book and Varda’s film here

In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argue that the ambiguous interplay of objective realism, subjective projection, and external narrational commentary is a major strategy of “modernist” cinema or “art cinema.” That argument is sketched in an earlier essay available here, with an update. See also the blog entry, “How to watch an art movie, reel 1.”

I played awhile with the idea that the floating voice-overs in the opening sequence might have been Duras’s efforts to capture what Nathalie Sarraute described as sous-conversation, the unarticulated subtexts that shape what we actually say. The historical timing fits, as Sarraute’s essay positing the possibility, “Conversation and sous-conversation,” appeared in early 1956. (See Sarraute, The Age of Suspicion: Essays on the Novel, trans. Maria Jolas, Braziller, 1963). But I’m not fully convinced of a direct debt. More generally, though, Sarraute’s insistence that the contemporary novel must replace external action with dialogue that hints at internal states seems in accord with the way Duras and Resnais conceived Hiroshima. Maybe here the image track does duty for Sarraute’s “subterranean conversation”? And perhaps the idea of sous-conversation is more relevant to Duras’s own films, particularly the masterpiece India Song (1975).

Hiroshima mon amour.