Archive for October 2018

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

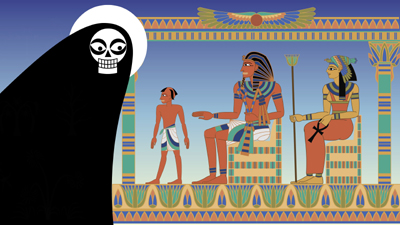

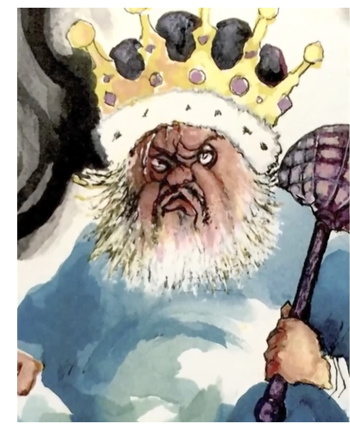

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

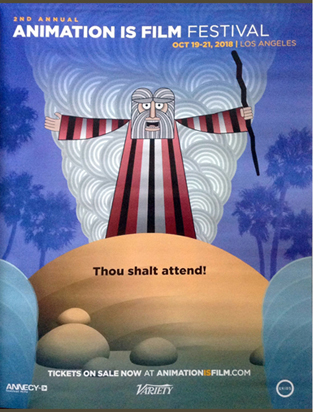

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).

Vancouver 2018: A Panorama of the Rest of the World

The Wild Pear Tree (2018).

Kristin here:

Venice, Telluride, and Toronto get a great deal of attention, since obsessive, year-round Oscar-predicting has become a way of life for some reviewers and industry commentators. In contrast, Vancouver has few premieres, but it quietly gathers up a huge international range of films, most of which have already played other festivals. It offers a chance to see fine films, many of which will never enter the radar of those who search only for Oscar bait. Venice and Vancouver, the two VIFFs, offer a perfect combination to keep us up-to-date.

There are several major threads in the program, including documentaries, socially impactful films of all sorts, Canadian films, and so on. I tend to favor the Panorama: Contemporary World Cinema thread, since it’s the one that basically breaks down the ROW (the Rest of the World) by country, and I try to see a wide range of world cinema. It’s also where familiar auteurs that I follow tend to show up.

This entry covers three films by directors whose work I have seen and admired, representing Iceland, Turkey, and Poland. More ROW films to come.

Woman at War (Benedikt Erlingsson, 2018)

Four years ago David reported on Icelandic director Erlingsson’s first feature, Of Horses and Men. This year we enjoyed his second, Woman at War. It tackles the difficult task of making a heroine who is basically a terrorist, though one might more tactfully call her an rather extreme environmental activist.

We first see her taking out the local power grid by firing a wire via bow-and-arrow over power lines in a remote rural area (above). She’s resisting a large Chinese investment in Iceland’s infrastructure, and she seems to be succeeding. The Chinese have postponed the deal, but she carries on her nearly one-woman crusade, aided only by a government official who is getting cold feet as the search for the “Mountain Woman” saboteur escalates, and an “alleged cousin,” a gruff farmer who rescues her more than once.

David praised how visually Erlingsson told his tale in Or Horses and Men. The same is true for the long scenes of Halla’s forays into the countryside for her subversive errands, as well as her preparations. She is clearly a highly adept and well-equipped saboteur, and she’s bold and skilled enough to outfox the military pursuers who send helicopters and drones after her.

Despite the serious theme, Woman at War is a lighthearted film. As Variety reviewer Jay Weissberg put it, “Is there anything rarer than an intelligent feel-good film that knows how to tackle urgent global issues with humor as well as a satisfying sense of justice?” One could called Halla a terrorist, but the audience we saw it with was clearly on her side, hoping for her to escape at each narrow brush with the law.

The whole thing is funny enough to be termed a comedy, or at least a dramedy. Halldóra Geirharðsdötter makes Halla an irresistably likeable character, and Erlingsson gives her emphatically ladylike activities in her life outside her clandestine campaign: she conducts a local choir and is in the process of adopting a Ukrainian orphan.

One daring move that Erlingssohn makes is to put the musicians playing the accompanying musical track onscreen, both a chamber group of three male instrumentalists who crop up nearly everywhere Halla goes, and a trio of female singers in Ukrainian dress who appear in scenes relating to the adoption. At first this seems like a joke simply repeating the one early in Blazing Saddles where the hero rides past Count Basie’s Orchestra playing the apparently nondiegetic sound track in the middle of a desert. Here the musicians appear through most of the film. They help avoid having Halla alone onscreen for long stretches of time, they appear sympathetic to her changing situations and hence cue us to sympathize with her, and they provide part of the film’s comedy. They took some getting used to, but I think the “onscreen nondiegetic music” device worked overall.

Shortly after its premiere in the Critics Week thread at Cannes, Woman at War was picked up for North America by Magnolia Pictures. Audiences should give it a look, since it’s a real crowd-pleaser.

The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2018)

My entire knowledge and admiration of Turkish director Ceylan’s work come thanks to VIFF. In 2011 we wrote about Once upon a Time in Anatolia and in 2014 about Winter Sleep. This year The Wild Pear Tree is being shown.

It’s a very fine film, though I doubt audiences will embrace it to the extent that they did Once upon a Time in Anatolia or even the less popular Winter Sleep. The former may have qualified as slow cinema, but it had the advantage of being a mystery centered around a murder and a lengthy search for the missing body. In the process it became a character study and a quiet satire on the police. Winter Sleep was more talky, but it featured arguments between two witty people, a crotchety ex-actor and his acerbic sister.

In The Wild Pear Tree, Ceylan tackles the challenge of another film with long conversations. But this time the plot centers around Sinan, an opinionated, bitter, argumentative recent college graduate returning to his hometown. He is, in short, an obnoxious protagonist, and we’re attached to him in nearly every scene. He argues with his father, a teacher with a serious gambling addiction that has impoverished the family, with his mother, whom he blames for putting up with his father’s problems, and with essentially with anyone else he encounters.

Sinan’s stated goals are simple: to publish a book of his own poetry and fiction and to become a teacher in the eastern part of Turkey, as his father had early in his career. He also reluctantly faces performing his required military service. Yet he doesn’t study for the teaching exam, perhaps out of laziness or perhaps because he fears following in his father’s footsteps.

The result is a film that I found more admirable than likeable. Certainly its portrait of Sinan captures a certain recognizable type of self-assured, stubborn character, and there is a certain humor in that portrayal.. The highlight for me was a lengthy conversation between Sinan and Mr. Süleyman, a successful local novelist whom he spots at work in a local bookshop. Receiving permission to ask a single question of the man, he sits down and proceeds to question him at length, in the process managing to imply that he knows more about writing than Süleyman does. Sinan even pursues him out of the store and down the street, arguing, until Süleyman finally loses his patience and berates the young man. Any professor will recognize this spot-on depiction of a tiresomely persistent, argumentative student.

I found the ending a bit too pat and easy. Sinan’s military service, rendered in one relatively brief shot, apparently purges him of much of his anger with his life, and the final reconciliation with his father seems to come far too easily.

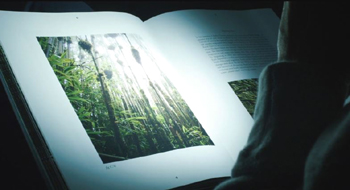

The film is beautifully photographed (see top), as always, by Gökhan Tiryaki, this time using a Red 6K digital camera.

Cinema Guild plans an early 2019 release for the film in North America.

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2018)

Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski’s first feature film since the award-winning Ida (2013) is quite a departure from that film’s austerity, despite again being beautifully filmed in black-and-white film with an Academy aspect ratio. It follows the tempestuous relationship between a young singer and the composer-pianist who mentors her and becomes her lover. The backdrop is the era from 1949 to the mid-1960s, set mostly in Poland but moving among the European cities that the pair visit, alone or together.

Cold War establishes an immediate appeal by showing a man, Wiktor, and his partner Irena (professional and perhaps personal) making ethnographic recordings of untutored peasants singing and playing traditional folk songs. The pair join the faculty of a state school for young singers, instrumentalists, and dancers. One auditioning singer, Lula, attracts Wiktor, and the two are soon involved in an affair that lasts, on and off, until the end of the era.

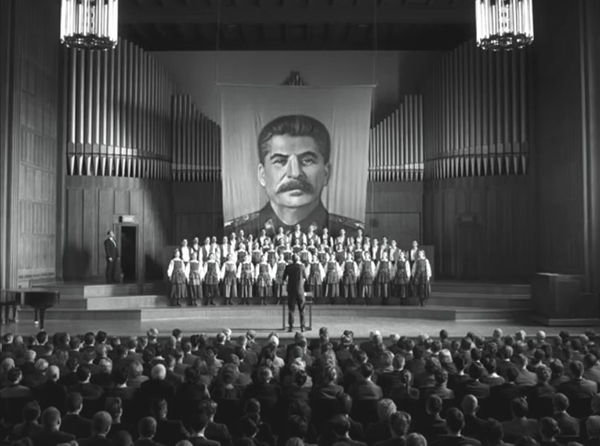

The film’s first half is fascinating, with its presentation of Polish folk-songs and dancing. The troupe formed by the school’s students becomes a success by presenting more professionally rendered versions of the folks songs and dances that had been collected. It soon attracts the attention of Communist authorities who pressure the Wiktor, Irena, and the manager, Kaczmarek, to add pro-Stalinist numbers to their program, and soon the group is singing “The Stalin Cantata” to equal success (see bottom).

Scenes fade to black at intervals, with the new scene appearing with a title giving the time and place of its action. These temporal jumps forward become more frequent as Wiktor becomes disgusted with the government’s control over the group’s program and flees to Paris. Thereafter the original troupe is left behind, and we see a series of scenes in which Lula’s path crosses Wiktor’s.

The result is that the second half of the film seems sketchier and less interesting. The action repeats, with variations, and the music that the pair perform is more familiar.

The highlight of this late part of Cold War is a scene which breaks loose briefly from the lovers’ travails. Lula and Wiktor at in a bar, and she, thoroughly drunk, initially begins to dance by herself to “Rock around the Clock.” In a remarkable long take, the camera moves among the wildly dancing couples as Lula passes from one partner to another and other couples pass by in the foreground and background (above). The moment must have been carefully choreographed, with the camera always capturing key moments of Lula’s enjoyment of the music, while simultaneously suggesting spontaneity and the crowd’s utter abandon to the music.

Cold War‘s music has been singled out by reviewers as a crucial ingredient. The film begins with craggy peasants performing genuine folk music in a muddy street and eventually takes us to Lula tarted up in a black wig and sequined dress singing a bizarre Polish version of “Baio Bongo,” a popular South American import deemed safe for audiences in the Soviet sphere. In between there are folk songs and dances, Stalinist choral propaganda, jazz, torch-song versions of the folk songs heard earlier, and rock-and-roll.

The film provides almost no background information about the two main characters or what they do in the several temporal gaps, some years long, covered by those fades. This makes it difficult to sympathize deeply with Wiktor and Lula’s long, ill-fated romance.

Pawlikowski in fact concocted some backgrounds for them, which he discusses in the film’s pressbook (posted in its entirety on Antti Alanen’s blog) .It draws upon extensive quotations from the director. There is considerable information about the historical, political context, including the fact that Wiktor and Lula are based on his parents. There is also discussion of the music, cinematography, and casting.

Pawlikowski speaks of the frequent ellipses as the film jumps forward in time:

Very often films, especially biopics, are weighed down by the need to feed information and explain; and the narrative is often reduced to causes and effects. But in life there are so many hidden causes and unpredictable effects – so much ambiguity and mystery that it’s hard to convey it as conventional cause and effect drama. It’s better to just show the strong and significant moments in the story and let the audience fill in the gaps with their own imagination and experience of life.

Reading the pressbook, I found myself wishing that at least some of the information therein could have been included in the film. There certainly would be time, since Cold War runs about 80 minutes sans its credits.

Amazon acquired Cold War for North America last year after its premiere at the Berlin Film Festival. It has announced a December 21 limited theatrical release.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Cold War (2018).

Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors

The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018).

DB here:

If you want to make a biographical documentary, you face problems of structure. Do you go chronological—start with birth, go through youth, maturity, and death? Or do you start in medias res, at the peak of fame or the depths of failure, and flash back to origins and development? Or do you do something else altogether? These are essentially the same problems of narrative that face the fiction filmmaker, but of course the documentarist also confronts gaps in the record, incompatible information, and the prospect that the story has been told before and may benefit from a fresh perspective.

Two documentaries at Vancouver tackled these problems in instructively different ways.

How to become famous: Work very, very hard

True to its title, Jane Magnusson’s Bergman: A Year in the Life picks Ingmar Bergman’s breakthrough in 1957 as its through-line. It was indeed quite a year: The Seventh Seal opened in January, Wild Strawberries in December, and Brink of Life was filmed in between (to open in early 1958). Very soon, Bergman won acclaim as one of cinema’s greatest artists. In the same annus mirabilis Bergman directed a TV drama and four theatre productions, including a monumentally successful five-hour version of Peer Gynt. All this he accomplished while suffering intense stomach pain; for part of the year he was in the hospital.

To survey only the events of January through December would leave us in the dark about the director’s full accomplishment, so the calendar format becomes a sort of clothesline on which incidents from all across his life are pinned. Since Bergman’s published memoirs are notoriously unreliable, Magnusson says that the films are more faithful records of his life and obsessions. But she also opens up many documents that fill in or correct his account, and the result becomes a fairly chronological survey.

For example, early in the documentary we learn of Bergman’s real relation to his father, his youthful admiration for Hitler during his stay in Germany (“I shouted like the others. I raised my hand like them”), and his first lover Karin Land, a spy for Finnish intelligence. As the film proceeds through 1957, it surveys his prior career and points ahead as well. Through associational links, motifs in The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, along with a survey of his childhood and his sexual partners, in effect provide flashforwards to Persona, Fanny and Alexander, and other later works.

The wellsprings of Bergman’s astonishing 1957 output are only hinted at. He was obviously a workaholic, as several commenters point out. One observer reminds us that Fassbinder had years that were as brutally productive, but he owed his stamina to drugs; for Bergman, the fuel was Swedish yogurt, Marie Biscuits, and sex.

Still, I wonder whether advancing through the Swedish film business, a rather industrially strict one, may have accustomed him to a killing pace. He started as a screenwriter at age 26, and he took up film directing two years later (not an uncommon age to begin). From 1948 on, he often signed two films a year as director and a third as a writer. You could make a case that his first breakthrough was really 1953, with the remarkable duo Summer with Monika and Sawdust and Tinsel. From the start, he was directing plays as well; in that same 1953 he mounted five. 1957 seems a landmark because the two films of that year became official international classics, winning festival prizes and wide distribution, but the man’s volcanic drive seems to have been there for a decade before.

In any case, the year-in-the-life format provides a handy point of entry into an astonishing, lengthy career. Magnusson has excavated many valuable documents and collected striking testimony, not least from coworkers whom the great man energetically humiliated. I learned a lot, not least that you can free up your documentary from the constraints of sheer chronology.

The Great Man draws

The same lesson issues more strikingly from Mark Cousins’ essayistic The Eyes of Orson Welles. Welles was of course another workaholic, moving across media freely. His energy was no less titanic than Bergman’s. For years we’ve known Welles the stage director, Welles the radio impresario, Welles the actor, and Welles the moviemaker. Now Cousins shows us Welles the graphic artist, and it’s a captivating, revelatory angle.

Welles started drawing as a child, and he later declared that painting was more important to him than filmmaking. Cousins examines hundreds of pictures archived at the University of Michigan and held by Welles’ daughter Beatrice. His film argues, with shrewd penetration, that a pictorial sensibility was central to Welles’ creative project. “You thought with lines and shapes. Your films are a sketchbook.”

How to structure this exploration? The film appears to offer trim boxes within boxes. Framing it all is a letter written and spoken by Cousins to the departed Welles. That apostrophe is in turn broken into numbered parts, some of which are in turn chopped into short topical segments. But these are engagingly digressive and untidy. For instance, part 3, devoted to Welles’s loves, skips from love of places, to love of vision itself (and Dolores Del Rio in Bird of Paradise), to love of chivalry, to omnivorous love (male friends), and finally to guilt over the death of love. A bit of Borges, a dash of Chris Marker: the swarming categories rub together in a cubistic way that Welles himself would probably have enjoyed.

In this porous, expanding design, Cousins takes us through familiar biographical terrain. The idea of Welles the graphic artist functions like 1957 in Magnusson’s film, a convenient wedge to open up episodes from family life and professional career. But Cousins brings out the pictorial side of well-covered material, such as the stage designs for the Harlem Macbeth. And he gains a lot from the frankly personal perspective. By writing a letter, he can ask rhetorical questions, mull over associations, imagine how Welles would view the modern world, and freely speculate on hidden autobiographical elements. “You wanted to be Falstaff, but you were Prince Hal.”

I came to Cousins’ film expecting a treatise on Welles’ cinematic style, and we get doses of that, but in unexpected ways. It turns out that most of his drawings don’t look a lot like his shots. Cousins floats the idea that Welles’ stay in Chicago, city of skyscrapers, may have tutored him in the low angles we see in his movies, but this seemed to me a stretch. Sketches of faces do, however, remind us of his fascination with actors, and of course his plans for sets, both on stage and on film, are very revealing.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

The obvious comparison is with the drawings of Eisenstein, perhaps more skillful than Welles’s, but equally suggestive of the filmmakers’ obsessions. Like Eisenstein as well, Welles shows a rueful humor in his sketches. Cousins acknowledges this streak in yet another section, a hypothetical posthumous reply from Welles to Cousins’ letter. Welles chastises his biographer for playing down the lighter side of his films and pictures. This is nicely illustrated by charming drawings for Christmas cards Welles sent his children. But Cousins shows the fun running down. Over the years Santa’s face droops and wobbles, the eyes grow hollow and the mouth goes slack. Santa as another ageing Welles tyrant? A teasing juxtaposition like this offers another reason to let The Eyes of Orson Welles train ours.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

For more on Bergman and Welles, see our categories devoted to the directors, on the right. A list of Bergman’s productions in film and other media is here.

Bergman: A Year in the Life (2018).

Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined

Shoplifters (Kore-eda, 2018).

DB here:

We’ve been attending the Vancouver International Film Festival since 2004. (The entries are tagged here.) It’s provided us many of our happiest viewing experiences, and this year is proving just as exciting. In particular, the festival’s long commitment to new films from Asia hasn’t flagged. Thanks to programmers Shelly Kraicer and Maggie Lee there has been plenty to showcase trends in Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, South Korea, and other lands. We won’t, unfortunately, be here for Hong Sangsoo’s Grass, but here are interim reflections on four items that we’ve seen in our first days.

Families, fraught and fragile

Shoplifters.

Girls Always Happy is a quiet but ingratiating first feature from Yang Ming Ming. Mother and daughter are both writers, and they struggle to live together in harmony while hoping for a legacy from Grandfather and for some resolution in their love lives. Yang says that she based the film on her own life, which rings true when you consider the range of emotions that well up. The two women tease each other, insult each other, ravenously devour meals together, shop partly to annoy sales staff, and sometimes burst out in screams. Reconciliations may be temporary but are still heartfelt.

With the two of them jammed together in a hutong, a neighborhood of cramped old ground-floor apartments, their jousts take on an intensity captured by Yang’s exceptionally tight framings and rapid cutting. Yang storyboarded the entire film, which allowed her quite precise control of composition and focus.

The relentless close-ups allow both psychological intimacy and subtle performances, as well as comparison of eating styles. Trips outside—Wu on her scooter or in her lover’s modern apartment, the mother at a hair salon—provide a respite from what’s essentially a series of escalating two-handed combats. The final shot is a lengthy take that carries our heroines forward into their city. Yang explained in the Q & A that after a film full of fast cutting and lots of talk she decided to end with the sort of long take Chinese filmmakers favor. In this context, with a canny use of a bus’s rearview mirror, the shot becomes an exhilarating, floating passage into the Beijing night.

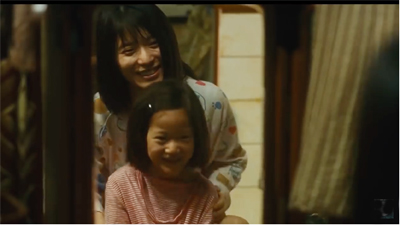

Girls Always Happy came to VIFF garlanded with awards, including prizes from both the Berlinale and the Hong Kong Film Festival. Even more honored was the latest by Kore-eda Hirozaku, The Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s another of his family dramas (we’ve discussed Still Walking, I Wish, Like Father, Like Son, Our Little Sister, and After the Storm), but here the notion of family is given an uncanny twist at the end.

Each member, as per Kore-eda’s habit, is given a specific, respectful delineation. There’s the happy-go-lucky Osamu, a day laborer who both coddles the boy Shota and leads him into petty crime. There’s the maternal Nobuyo who works at a dry-cleaning facility and pilfers what she finds in pockets. Twentysomething Aki works at a sex club flashing her breasts and bottom at men crouched behind one-way mirrors. Grandma keeps the group going with her pension, her pachinko-playing, and some secret sources of income. Into this household comes Yuri, an abused child brought home like an abandoned cat.

Like Tsai Ming-liang’s more somber Rain Dogs, this is a film about people on the margins. The kids don’t go to school; Shota teaches Yuri the tricks of shoplifting, while Aki warms to a sex-club client. As in Girls Always Happy, interiors are sharply distinguished from exteriors, but not by close framings and shifting focus. Instead, master shots fill the frame with the detritus of seven people jammed in together. (See shot above.)

In a film so concentrated on characterization, we naturally get the sort of privileged moments that Kore-eda excels in. Osamu pauses in his construction work to stand looking around an unfinished apartment—a modest one, but a home he can never have. The young kids collect cicadas. Aki cradles a lonely punter in her lap. Nobuyo consoles Yuri by comparing the girl’s scars to burns Nobuyo has accumulated from ironing clothes. Grandma, watching her charges play on the beach, pours sand to cover the age spots on her legs. The ensemble comes together in moments of shared joy at the seaside or watching the fireworks at the Sumida River festival.

But these moments don’t prepare us for the unsettling revelations about the characters’ pasts that we get in the last half hour. Even here, though, the details of behavior remain indelible. One astonishing shot turns a cinematic staple—a woman trying to wipe away tears—into a tour de force of facial performance by Ando Sakura.

The Shoplifters reminded me of Ozu’s Passing Fancy and Inn in Tokyo, obliquely but sharply condemning the economic conditions that push people into wayward lives. It’s a gently subversive film about people flung together resourcefully trying to survive and find happiness by flouting the comfortable norms of middle-class morality.

Time out of mind

A Land Imagined.

Lush Reeds, by Yang Yishu, has plenty of the long takes that Girls Always Happy avoids. In nearly abstract framings, newspaper reporter Xiayin moves through minimalist offices and country lanes, bleak apartments and dense foliage.

As in many postwar films, drama sometimes becomes subordinate to the walks taken by the protagonist into an overwhelming, mysterious environment.

Against the wishes of her politically cautious editor Xiayin inquires into complaints of rural pollution. At the same time, she’s pregnant and is growing distant from her fairly cold husband. Her visit to the countryside becomes a threatening experience that brings to light parallels between the death of a villager and the apparent suicide of a fellow reporter.

The film is less linear than I suggest. Yang breaks up the story into midsize chunks and sets them out of order, so that some images–a little girl who meets Xiayin in the village, a shoe on a riverbank, the rescue of a suitcase from a rubbish depot–could fit into one time frame or another. Yang is even so bold as to run the title credit again midway through the film, suggesting that what follows might be backstory, or imagination, or an alternative film, or something in between.

A similar ambiguity pervades A Land Imagined (2018), another prize-winner (Golden Leopard, Locarno). It centers on a migrant worker Wang working at a Singapore site devoted to extending the coastline with sand dredged up or brought from other countries. Wang has disappeared, and the investigating cop Lok soon learns that Wang’s Bengali friend Ajit has vanished as well. A flashback takes us into the backstory, showing Wang spendiing his nights at a cybercafé and getting harassed by a troll who invades his videogame screen. Wang also begins a chaste affair with the tough gamine Mindy who oversees the game parlor. Eventually the flashback turns into a parallel, dreamlike narrative, with Ajit by turns dead and alive and Lok reenacting scenes involving Wang.

Director Yeo Siew Hua has given this noirish tale an appropriately lustrous treatment, with saturated long shots of black derricks looming against a red sky or sunk in sickly orange murk. Lyrical slow-motion musical interludes enhance the dreamlike ambience, and there’s a post-Wong-Kar-wai freedom of camera placement in the candy-colored cybercafé.

In his comments after the screening, Yeo spoke of trying to provide a counter-image to “the postcard, Crazy Rich Asians” depiction of Singapore. The shifting time frames and uncertain stretches of subjectivity are connected, for Yeo, with a sleeplessness suffered not only by the main characters but also by the population at large. The “land imagined” isn’t only the sand that expands the contours of the shoreline but also the hallucination of a hypermodern city state built on the labor of workers who can conveniently go missing.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Girls Always Happy.