Archive for January 2019

Nolan book 2.0: Cerebral blockbusters meet blunt-force cinephilia

You want to go see a film that surprises you in some way. Not for the sake of it, but because the people making the film are really trying to do something they haven’t seen a thousand times before themselves. . . I give a film a lot of credit for trying to do something fresh—even if it doesn’t work.

Christopher Nolan

DB here:

Christopher Nolan has scheduled a new film for summer 2020. That’s all we know at this point. It’s a nifty coincidence that this week we’re releasing the second edition of our little e-book, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. It’s now available for purchase at $3.99.

Kristin and I have rewritten and expanded the 2013 edition to include discussions of Interstellar and Dunkirk. In addition, I’ve taken the opportunity to develop some new arguments about Nolan’s career. In particular, I claim that he has developed a consistent and fairly adventurous “formal project” revolving around the treatment of cinematic time. I also consider his efforts to make what the industry calls “event films” and The Hollywood Reporter calls “cerebral blockbusters.”

My online exploration of those ideas got me into trouble some while back. A well-known critic vehemently criticized my blog entry on Dunkirk while announcing that he refused to read it. His Facebook fulminations taught me a few things about internet culture and film reviewing, and I’ll try to spell some of them out shortly. First, though, let me introduce the new version of our book.

Preview

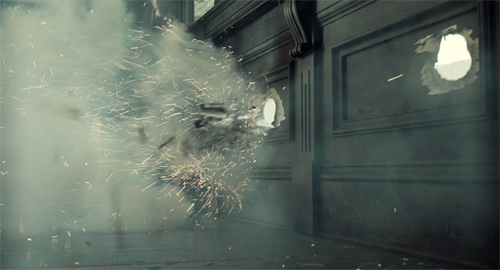

Dunkirk (2017).

The earlier edition was in portrait format and contained embedded video clips. The new version is squeezed into the more grateful landscape format and contains links to online clips. This makes the file less bulky to download. As you’d expect, we’ve added more clips, from The Prestige, Interstellar, and Dunkirk.

The book’s argument has four strands.

(1) Nolan is best understood as working with traditions and trends in contemporary American cinema. Following and Memento blend classic studio conventions (chiefly of film noir) with independent cinema’s tendency toward “complex storytelling” at the end of the 1990s (partly due to Tarantino’s influence). His Dark Knight trilogy aimed to bring serious themes to the emerging comics-superhero model. Our book has little to say about the Batman franchise, except insofar as it encouraged Nolan to try various stand-alone experiments.

A trend toward “intellectual” genre cinema, seen especially in The Matrix (1999), gave Nolan the opportunity to make his “cerebral blockbusters”; the Wachowskis’ film became a model for Inception. Important as well was the impulse toward richly realized story worlds (“worldmaking”) pioneered by Lucas’s Star Wars franchise and carried along in the fantasy and SF genres.

(2) Contemporary American cinema has enabled a few directors to launch “formal projects.” A filmmaker can develop a signature style or method recognizable from film to film. Wes Anderson is perhaps the clearest example in the US, although Hong Sangsoo is a good overseas instance. I argue that Nolan quite self-consciously launched a distinctive formal project in his work, applying it to a variety of subjects and genres. A new chapter develops this idea.

What is this formal project? I’d say it consists of experiments with cinematic time by means of techniques of subjective viewpoint and crosscutting. From Following to Dunkirk, Nolan has explored various ways of manipulating story time and the viewer’s experience of it. I devote a new chapter to spelling out the idea, taking seriously his emerging idea of a “rule set.” The rule set not only governs the film’s construction but becomes a guidance device that spectators must learn to understand the story.

After using Following and Memento to illustrate Nolan’s overall project, the book devotes later chapters to showing how rule sets shape The Prestige’s dual-protagonist plot, Inception’s nested-dream device, Interstellar’s time-travel agenda, and Dunkirk’s three levels of story duration. In the course of these chapters, I try to show how Nolan addresses criticisms that his work is emotionally cold (one chapter is called “Pathos and the Puzzle Box”) and how he has managed to develop his project in the framework of genres and studio “event pictures.” The biggest challenge is clarity: keeping the audience up to speed with story action when plotting and narration are fulfilling the sometimes arcane rules.

(3) The first edition of our book began by acknowledging that Nolan’s work divides audiences. Many film viewers like his films, some consider them masterpieces, and others consider them worthless. Here’s the new book’s opening, slightly modified from the first edition.

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other American directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

As of fall 2018, his films have earned over $4.7 billion at the global box office, and at least as much from cable television, DVD, and other ancillary platforms. On IMDB’s list of the top 250 movies, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) currently ranks number 4 with nearly two million votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned over 1.7 million. Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Peter Jackson each have three films in the poll’s top 50. Nolan is the only director to have five.

Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s blockbusters and his more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006). From Following (1998) onward, his films have won between 76% and 94% “fresh” ratings on the aggregating website Rotten Tomatoes. Even Insomnia (2002), probably his least-discussed film, earned 92% “fresh.” Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet some critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. People who shrug off patchy plots and continuity errors in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The vehemence of the attack is probably in part a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

More on the critical controversy below. At this point, it’s enough to say that our book argues that Nolan’s formal project illuminates certain capacities of cinema. He shows us some new things that cinema can do.

Innovation, then, is another strand in the argument. We pick up on Nolan’s suggestion that all other things being equal, innovation is worthwhile. (“I give a film a lot of credit for trying to do something fresh….”) Our opening chapter (“How to Innovate”), retained from the first edition, continues:

I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear. I have some reservations about them too. Yet I think that all parties will agree that Nolan seeks to be an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and originality in popular cinema.

After decades of trying to trace the bounds of novelty in popular cinema, I think that Nolan’s work shows that the conventions of popular cinema are intriguingly flexible. As in the silent era (see many of our entries, especially those on the 1910s), as in the 1940s (see Reinventing Hollywood), as in the 1990s (see The Way Hollywood Tells It)—today’s American cinema can accommodate intriguing experiments in storytelling. There are limits, of course, but they aren’t as rigid or strict as some think.

Put more theoretically, the capacity of classical storytelling to exhibit “trended change” allows classical principles to be instantiated in various unforeseeable ways. This entry explains the argument a bit more.

4) Where does this leave the critics who despise Nolan’s work? The book argues that critics should be more open to the cinematic implications of the movies they encounter. They shouldn’t consider a film they may dislike merely as something to be dismissed or another nail in a despised director’s coffin or an occasion for displays of writerly cleverness. (The recent victim is Serenity. Maybe the umbrage is deserved, but it makes me want to take a look.)

Critics concentrating on evaluation can miss how even films they don’t consider good or likable can shed light on the possibilities of cinema. As our introduction puts it:

Taking this stance suggests that it can be useful to look at the artistic history of films apart from our urge to rate goodness and badness.

Once again, I find myself agreeing with Nolan’s remark quoted at the top of this entry. Even though something fails, it can be worth trying if it opens up some creative possibilities. Critics could signal these, if they chose.

These four ideas, along with detailed analyses of Nolan’s films, form the substance of the book. You can buy a copy on our order page, which contains more information and a table of contents.

The follies of Facebook

After the internet, nothing seems weird. Still, the August 2017 email from an overseas friend took me by surprise. It was headed “Re: Rosenbaum” and began: “What a turd!” before continuing in a similar vein.

Jonathan Rosenbaum has my permission to stop reading this now.

I don’t do Facebook or any other social media myself, so I had no idea what my friend was referring to. Using Kristin’s account, I learned that on a Facebook page JR had posted the remark you see above in response to my blog entry on Dunkirk. (That entry has developed into a chapter in our book.)

I was mostly bemused by the Facebookery. Actually, I didn’t understand it.

I didn’t understand the reference to Lars von Trier, whom JR has praised many times.

I didn’t understand what was desperate about my effort to grasp Nolan’s latest release as part of a larger trend toward event films as “personal” projects, typified in earlier times by Kubrick’s work.

I didn’t understand the objection to my use of “our,” which the entry clearly indicates as referring to mainstream US film culture today.

I didn’t understand how I could stagger someone by comparing two notable filmmakers. Nothing I said in what followed suggested I was comparing them on grounds of quality. Indeed, had JR checked our blog or read our book, he’d learn that I’ve written about both flaws and strengths of Nolan’s work.

Above all, I couldn’t understand why someone would refuse to read further, and then proudly tell his Facebook Friends™ he did it. This seems curiously close-minded, especially when six minutes of Googling dredges up many passages in which JR castigates critics for refusing to see movies they comment on.

Wolcott’s deepest scorn was reserved for those “sullen Village Voice reviewers” who “praise movies so obscure that simply getting to the theater counts as a quest for the authentic.” One of them, he pointed out, had the nerve to write hyperbolically about a recent Godard video — something that Wolcott presumably couldn’t be bothered to see himself.

“[Godard’s] most recent films,” I concluded, “are simultaneously investigations into and lessons about how to see, hear and understand our everyday existence. Regardless of how one ultimately judges them, it is irresponsible to call them frivolous; far more frivolous is the critical intelligence which refuses to grapple with them.”

I saw as well that some of his Friends™, who also had not read the piece, had joined the chorus. Still, Facebook isn’t exactly an arena of Ciceronian subtlety. So I shrugged. Why not let JR and his Friends™ blow off steam?

But a few of his Friends™ bothered to read my piece and pointed out that his reaction misunderstood my points. And some who hadn’t read the piece began treating my first sentence as an essay question in Contemporary Movies 101 by speculating on what evidence might warrant it. Indeed, some of his readers arrived at claims akin to mine.

JR responded by escalating. He had to go and compare me, on obscure grounds to Trump–a figure I’ve castigated on more than one occasion. To this I demanded an apology.

JR replied on Facebook with an excuse masquerading as an apology. As I’d predicted, he shifted the grounds of the original objection. Turns out it was my fault: he claims that my first sentence misled him because it was so poorly written. (Sorry to report, it remains in the Nolan book.) The whole thing–starting silly, turning a bit nasty, and ending with the critic scuttling off trailing a cloud of muttered gripes–exemplified yet again the superficiality that Facebook encourages.

My email correspondent might call it a close encounter of the turd kind. Still, I think I learned things. I began to think again about how criticism that depends heavily on evaluation can lead to a dogmatism about taste and a close-mindedness that blocks intellectual inquiry.

Call it blunt-force cinephilia.

A brief guide to militant cinephilia

Petulia (1968).

In an earlier entry, I argued that critics do lots of things with language. They describe artworks; they analyze them; they interpret them; and they evaluate them. Typically, academic critics concentrate on description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation usually takes the back seat.

By contrast, journalistic critics, aka reviewers, heavily weight evaluation. After minimally describing the film, they offer consumer recommendations. They guide us to recent releases that they favor and steer us away from ones they don’t. But evaluation, I claimed, can appeal to two standards: more or less objective criteria of judgment and more or less subjective tastes. The reviewer may appeal to criteria that readers share (a thriller shouldn’t have plot holes, a comedy should induce laughter), or to tastes.

Tastes are subjective, but they’re also shared with others. I like even somewhat cheesy kung-fu films, and maybe you do too. I’m not prepared to call them excellent on objective criteria, but they give me pleasure. A reviewer often signals a film’s taste dimension with “If you like this sort of thing, you’ll probably like this new film.”

But some reviewers, as they acquire knowledge of films and film history and film culture, build up a cluster of distinctive tastes. And some reviewers become well-known, and they gather followers. Soon the critic’s preferences and hatreds become part of the critic’s public identity, and the followers align their tastes, to one degree or another, with the critic’s.

And when a critic becomes a celebrity, he or she may be tempted to make tastes part of the brand, to minimize judgment based on criteria and exaggerate the importance of tastes. And to whale away on films aimed at alien tastes.

One branding option, popularized I think by Pauline Kael, was a sort of weaponized evaluation. Bad films weren’t simply slipshod or shallow, but they were outrages, profound insults to cinema and humanity. “Is there any art in this obscenely self-important movie?” Kael asked of Petulia.

Militant cinephilia of this sort offers all sorts of rhetorical advantages. It paints the possessor as a pure guardian of what’s valuable. It allows the critic to write wildly, spraying bullets at many targets, so it has a jittery readability. It encourages hatchet-wielding, since most films won’t measure up. Demolition jobs, like Godzilla movies, are fun.

Dogmatic cinephilia also favors the narcissistic personality who disdains dialogue or common pursuit of ideas. And it glamorizes the critic’s brand. Who would want to be sane, reasonable Stanley Kauffmann if you can cheer Kael wrestling with the demons of commerce? This is how cults of personality grow.

Militant cinephilia rests largely on the critic’s taste arsenal. Deployed carefully, it can yield good results–stimulating conversation, pointing out faults and beauties in films. But cinephilia turns dogmatic when the tastes keep you from considering evidence or alternative arguments. Ironically, the dogmatic cinephile winds up limiting cinephilia, and cinema itself.

As a sketch, I’d offer this list of symptoms of blunt-force cinephilia.

You see it or you don’t. The critic makes sweeping claims, usually in the form of piled-up adjectives, without much evidence.

Differ if you dare. The critic simply negates any opposing views by attributing disagreement to base motives or a blinkered assimilation to dominant tastes. You cashed in, sold out, unthinkingly accepted what you were told.

Fondness for the sideswipe. If dogmatic cinephiles were forced to justify their claims in some detail , they might nuance them. But reviews, like Facebook postings and tweets, have to be brief. (No time or space to go deep.) They favor short, sharp bursts of dislike, zingers, what in another context Matt Taibbi calls “anger chiclets.” The same scattershot approach can be found in longer pieces as well, where a celebrity critic can pile up strings of pans or panegyrics.

My cinephilia can lick your cinephilia. When you overstate (or “overreact,” as JR puts it in his Facebook apology), as you inevitably will, it’s because you just love cinema so much. Your passion is so volcanic that of course sometimes it will burst the bounds of reason. Never say “It’s only a movie!” Movies matter tremendously! See how much I care? My vehemence is righteous, and I smite the sinful.

The mutation of militant cinephilia into dogma brings us back to JR’s outbursts. If you’re a critic defining yourself largely by tastes, my fairly bland sentence about Dunkirk can look like an armed provocation. Dogmatic cinephilia can operate on a hair-trigger.

More basically, I suspect that JR doesn’t welcome film criticism that suspends or just ignores evaluation. But I think it’s not only possible but desirable to hold evaluation in check if we want to know how films work and work on us.

The writing we do on this blog and in our publications is of course fueled by love–of the medium, of filmmakers, and of films. Evaluation mostly enters as a choice of what to talk about. We tend to write about films we think are good by some criteria. Usually, we like them as well. Sometimes we try to convince you to rank them high and come to like them.

Still, many of our points should hold good independent of evaluation. Often we try to see films as affording glimpses into cinema’s artistic practices (conventions, strategies) and, when we encounter novelty, its fresh possibilities. This is at bottom the premise of the Nolan book.

Both journalistic reviewers and high-end critics often lack curiosity. They don’t seem to think that films can teach them anything about cinema they don’t already know. We, like Nolan in our opening quotation, want to be surprised by something, even if it doesn’t quite come off. At the limit, we try to learn things about cinema from films that others, or even we ourselves, might not like. That’s another valid way, we think, of being a cinephile.

For more on our Nolan book, see this entry.

An older blog entry considers other games cinephiles play.

Besides the Nolan book, what would criticism that plays down evaluation look like? Many of our blog entries and books try to hold judgment and tastes in abeyance in order to answer research questions about form and style. See, for an example of a film that has ardent supporters and skeptics, our entries (here and here) on La La Land. For a wider effort to compare several films without emphasizing value judgments, try my roundups of narrative strategies in releases of 2015 and 2017. Then there are the older essays on Mission: Impossible III and staging in 1910s Nordisk films. For more extended examples see the book Poetics of Cinema.

Interstellar (2014).

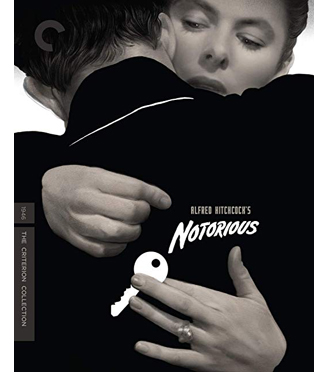

NOTORIOUSly yours, from Criterion

DB here:

Notorious was the subject of the first piece of criticism I published. The venue was Film Heritage, one of those little cinephile magazines that flourished, if that’s the word, in the 1960s. My appreciative essay came out in 1969, as I was finishing my senior year in college.

I haven’t dared to look back at it. Actually, I’m not sure I have a copy. The soft-focus imagery of memory tells me that some things that would preoccupy me in the future–interest in narrative structure, style, point-of-view, the spectator’s engagement with mystery and suspense–are there, though in ploddingly naive shape.

Since those days Hitchcock has always been with me. He’s been the subject of articles and blogs and many, many classroom sessions. Now, thanks to the Criterion collection, I’ve had a chance to revisit Notorious.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

Hitchcock is the most teachable of classic directors. His strategies are just obvious enough for beginners to notice them, but they always open up new directions for more experienced viewers.

I reconfirmed all this when I decided to devote a chapter of Reinventing Hollywood to Hitchcock and Welles. These two masters decisively influenced the 1940s, the period I was considering. But they were in turn influenced by the crosscurrents in their filmmaking community. And they came to epitomize, for me, the artistic richness of what Hollywood could do in this golden age.

In addition, I tried to make the case that they carried storytelling strategies typical of the period into later eras. I declared, in a burst of geek recklessness:

Vertigo constitutes a thoroughgoing compilation/revision of 1940s subjective devices. The obsessive optical POV shots of Scottie trailing Madeleine give way to a dream tricked out with pulsating color, abstract rear projetion, stark geometric patterns, and animated flowers. . . . Along with all the other echoes–portraits, therapy for a traumatized man, voice-over confession, point-of-view switches, the hint of a reincarnated or time-traveling woman–the powerful probes of subjectivity make Vertigo, though released in 1958, one of the most typical forties movies.

But then so is Notorious, a film I had little to say about in the book. So I’m glad that Criterion’s invitation to contribute a 30-minute short on this new release led me back to a film I’ve loved for over fifty years.

Darned sophisticated, or dead

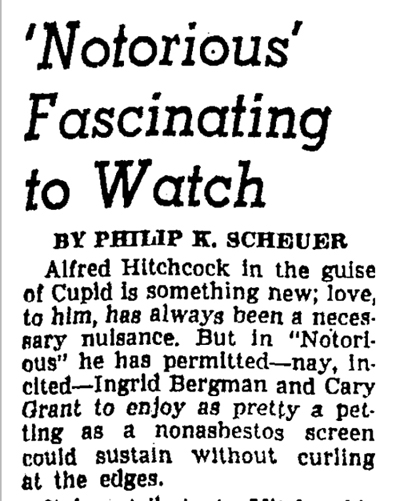

My supplement concentrates on the climax in Alicia’s bedroom and on the staircase of Sebastian’s mansion. Spiraling out from that sequence, I try to show how it’s the culmination of many storytelling strategies, from point-of-view editing to long takes. I also trace out something I didn’t fully realize until I researched the film’s reception: It was considered very sexy.

For one thing, Ingrid Bergman was associated with innocents, and her playing a promiscuous party girl (“notorious”) was a bit of spice. For another, Hitchcock’s earlier films, though they always had erotic overtones, didn’t really center on a passionate romance. His heroines didn’t convey much smoldering passion, despite all his prattle about glacial blondes thawing out fast. His darkly handsome protagonists (Maxim in Rebecca, Johnnie in Suspicion, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt) are more steely than steamy. As for Joel McCrae in Foreign Correspondent and Bob Cummings in Saboteur, they seem virtual Boy Scouts. Only Spellbound, which introduces a psychoanalyst to ecstasy in the rangy form of Gregory Peck, seems a first stab at the sexual complications of Notorious. And the analyst is played, of course, by Bergman, radiant as soon as she takes off her glasses.

The 1940s had a well-established convention that a handsome friend of the family could rescue a wife from the predations of her husband (Gaslight, Sleep My Love) or other tormentor (Shadow of a Doubt). Film scholar Diane Waldman called this figure the helper male. In the second half of Notorious Devlin plays this role. The basic situation–a man stealing another man’s lawfully wedded wife–is pretty edgy in itself, especially since Sebastian is far more frankly in love with Alicia than Devlin is. I try to show that Hitchcock wrings new emotion from the convention by making the husband, trapped between his Nazi gang and his ruthless mother, sympathetic. Meanwhile, the helper male comes off unusually cruel, needling Alicia about the carnal bargain he plunged her into.

And then there’s all that snogging. The romance in Notorious is one long tease–between the characters, and between the screen and the viewer. The Los Angeles Times critic made it the basis of his lead:

Devlin and Alicia are all over each other, notably in the famous scene in her apartment. (Have they done The Deed? Obviously yes.) Their tight embrace, their constant pecking and nibbling and nuzzling as they float across the room, provoked a lot of notice. In the supplement I quote Dorothy Kilgallen, whom my oldest readers will remember from “What’s My Line?” on TV. She wrote this in Modern Screen:

So it makes a certain amount of sense for a power company to assume that incandescent stars can sell electricity, as below. In Toledo, too.

For this and other reasons, I’m happy to have a chance to revisit one of my very favorite Hitchcock films. I bet that you’ll enjoy seeing this stunning copy and immersing yourself in all the bonuses. Hitch is endlessly fascinating, and he’s one of the main reasons we love movies.

Thanks to Curtis Tsui, who produced the disc, as well as Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison, and all the New York postproduction team. Thanks as well to Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson for all they do to keep Criterion at the top of its game.

Greg Ruth, designer of cover art for Criterion, explains his creative process on their site. More details on the release, with clip, are here.

The Los Angeles Times review comes from the issue of 23 August 1946, p. A7. The Kilgallen Modern Screen piece is available via Lantern, here. If you youngsters didn’t get her reference to Helen Hokinson, go here.

For another in-depth analysis of a single sequence, see Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin’s Filmkrant video essay, “Place and Space in a Scene from Notorious.” They showed me things I had never noticed–more proof of the richness of Hitchcock World.

Cary Grant’s image was used to sell oil a few years before, as illustrated in this entry.

P.S. 21 January 2019: For more on the steamy side of Notorious, there’s “The Clinch That Filled 1,200 Seats,” at the redoubtable Greenbriar Picture Shows. Thanks to John McElwee for bringing it to my notice!

Better Theatres (24 August 1946).

The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master class

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

DB here:

Craft isn’t everything in art, but it counts for a lot. Even when you’re going against tradition, you can’t just willy-nilly do whatever. You need to create a counter-craft (as Bresson, Brakhage, Ozu, and others showed us). Reviewers, in their urge to thump out quick judgments, often don’t address craft practice directly. So if we simply talk of the Coens’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs as a grim, occasionally grotesque and zany take on Western conventions, we’re apt to take for granted just what a trim, absorbing piece of sheer filmmaking it is.

It’s worth attuning ourselves to what Adam Gopnik called his collection of Robert Hughes’ writings: The Spectacle of Skill. Paying attention to that enhances our appreciation for what filmmakers accomplish, and maybe it can nudge aspiring filmmakers to consider things to try.

So, herewith a quick analysis of the very beginning of the film’s second episode. The whole piece is not as audacious as the title episode, and not as poignant as “Meal Ticket” or “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It’s more of a light interlude. But we shouldn’t let its shaggy-dog payoff (“Your first time?”) make us think there’s anything slapdash about it.

There follow spoilers.

All the meanness in the Used-To-Be

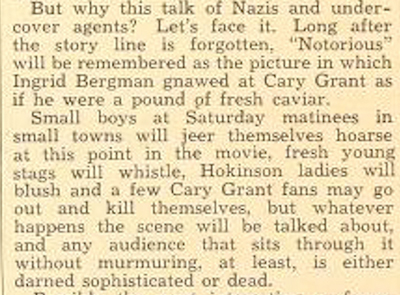

In the book that frames each tale, this one is called “Near Algodones.” As in the other episodes, an illustration prepares us for something we’ll see in the scene. The caption reads: “Pan-shot!” cried the old man.

Lesson 1: Make everything clear and simple, except what you want to suppress.

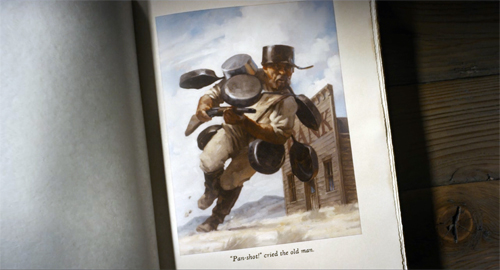

A master shot gives us the elemental situation: A bank, a well, and a lone rider with his horse.

These are the central components of the sequence. The isolation of the bank makes it a plausible target for a holdup. The geography will become important in the second stretch of the scene, while the well will provide cover to the Cowboy. His horse will prove notably reluctant to move.

Lesson 2: Attach the narration to a single character.

Throughout this episode, we’re “with” the Cowboy, not always through exact optical POV but more generally: our range of knowledge of the unfolding situation approximates his. This sort of restriction arouses curiosity (what’s going on in the bank?), as well as suspense and surprise (as we’ll see).

Lesson 3: Motivate new shots by offscreen sound.

Attachment to the Cowboy is reinforced by the play of his attention. Over the Leone-esque close-up we hear a creak. This motivates a cut to the bank’s hanging sign. As we hear a thump, he shifts his eyes; we see it’s caused by the bucket bumping against the well.

Lesson 4: Delay when you can.

Attachment doesn’t mean immersion. Instead of a shot from the Cowboy’s POV as he’s entering the bank, we get him pausing to size up the scene.

Only then do we get a shot of the bare bank and the teller’s windows, which (thanks to a wide-angle lens) seem impossibly far away.

Lesson 5: Let expectations go to work.

The holdup scenario, a convention of Westerns, is surely hovering in many viewer’s minds. When the Cowboy advances, we wait to see if our expectations pay off. You get suspense simply by having your actor move forward; what could be more economical?

Lesson 6: Prepare for later shots.

The tracking shot of the Cowboy’s boots and spurs might seem mere decoration, but it further delays his arrival at the window and sets up an important shot to come.

Lesson 7: Scale your shots according to the information they present.

Reverse shots are the workhorses of mainstream storytelling cinema. They are vehicles for character interaction, either based in dialogue or just the exchange of glances. The over-the-shoulder (OTS) version specifies the spaces the characters occupy, typically in a conversation. OTS framings also serve as a transition to closer views. Here the Cowboy’s goal in the scene is to learn how fortified the bank is against robbery.

After the opening stretch of purely visual storytelling, dialogue takes over. For us to grasp it better, the OTS framings give way to singles, which enlarge the teller’s performance and the Cowboy’s reactions.

The geezer’s chatter joins the motif of flowery monologues and eloquent bafflegab we’ll encounter throughout the film. The framing also lets us enjoy the performance, which suggests that this scatterbrain might be an easy mark. He does, however, mention that he has put down one attempted robber and “shredded the legs” of another.

The climax of the exchange is the Cowboy’s drawing his pistol and the teller’s explanation that he has to stoop to get “the large denominations.” The result is more shot-scale calibration: We need a single to see the gun looming (an OTS wouldn’t be as punchy), but the reverse shot can be OTS because we need to see how the teller’s stooping maneuver is concealed from the Cowboy. We are still attached to him and what he knows–or doesn’t know.

Another benefit: as variants of framings we’ve seen before, these let us quickly grasp what’s new in them (brandishing the pistol, ducking down).

Lesson 8: Use a cut, a crisp gesture, or a discrete sound to arrest attention.

Actually, the next shot does all three. The Cowboy tries to peer over the till, and a shot shows him taking a step forward as we hear a click. This framing pays off the shot of striding boots we saw in Lesson 6.

Within the same shot, the front of the teller’s window is blasted open. The Cowboy jumps sideways as another hole explodes, then another.

We’re back to visual storytelling. Now we understand why the teller has “shredded the legs” of another would-be robber. When the debris clears, a camera tilt shows that the Cowboy has sprung to the counter.

A mini-spectacle of skill: Handling the three blasts and the Cowboy’s evasion in a single percussive shot.

Lesson 9: Stagger the reveals.

Alexander Payne once remarked: “Whenever you can do a reveal, do it.” Here we have a suite of reveals, but they’re handled in a simple, cogent way.

When the Cowboy crouches on the counter, we have several questions. Is the teller going to fight? What created the blasts? And will the Cowboy get to the money?

These questions are answered, purely pictorially, in the shots to come. First, from his perch the Cowboy sees the partly open door. The teller has escaped, but because we’re restricted to the Cowboy’s perspective, we don’t know where he’s gone.

Just as one concise shot showed us the gunblasts and the Cowboy’s leap to the counter, now his descent and landing, followed in a single tilt, reveals the teller’s infernal machine: a row of shotguns poised to fire.

Another director would have devoted a POV shot to this revelation, but here it’s provided without fuss or forcing, as we follow the Cowboy’s crouch. He barely reacts and smoothly sets about finding the money. He grabs it in a single crisp close-up. And another cut takes us to the doorway, as the Cowboy hopes a view outside will reveal where the teller has gone.

Once more a POV is recruited, but it shows how much our protagonist doesn’t know.

The elements we were given at the start–bank, well, horse–are laid out again, from the opposite angle. Thanks to the clarity of presentation, we fully understand that the old teller is hiding somewhere (probably with his lauded scattergun) and the Cowboy has to make a run for it. But to where?

There are other things to talk about here, such as the homages to Leone (the mention of Tucumcari from For a Few Dollars More, the creaking of the sign recalling Once Upon a Time in the West‘s operatic opening). Perhaps the device of the book owes something to William S. and Mary Hart’s Pinto Ben (1919).

But we’re so used to considering the Coens pasticheurs that these allusions don’t interest me as much as the compact finesse of their style.

The rest of this scene will depend on reworking the narrative, auditory, and pictorial elements we’ve already encountered. You could go through that, and indeed the rest of the film, and trace the artisanal precision on display. (Let alone the sheer boldness of certain depth shots.) And the Coens are expert at using visual ideas for humor, as in the later scene when the Cowboy’s horse, browsing for more grass to nibble, stretches his noose-rope to the limit (see top image).

But I think I’ve said enough to indicate how rich an apparently straightforward handling can be. When we speak of careful pacing; when we think of building a scene; when we think of a movie that’s easy and graceful to follow, what Otis Ferguson called “a smooth clear line”–this is what we’re talking about.

There’s plenty of spectacle here, what with landscapes and gun blasts, but there’s another sort of spectacle as well: the quiet virtuosity of craft. You don’t see it that often these days, so when we encounter it, we should acknowledge it.

For another study of the Coens’ technique, see Jim Emerson on No Country for Old Men.

Other blog entries celebrate this sort of precision. See, for example, this analysis of Panic in the Streets, or the mind-boggling visual engineering of Fritz Lang (here and here). Otis Ferguson’s ideas about smooth cinematic storytelling are discussed in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

My first impressions of Scruggs, after seeing a magnificent big-screen presentation in Venice, are here. Netflix and Annapurna are to be congratulated for backing this movie, but it really deserves a wider theatrical release than it got. At least, please give us a Blu-Ray!

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).