The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master class

Sunday | January 13, 2019 open printable version

open printable version

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

DB here:

Craft isn’t everything in art, but it counts for a lot. Even when you’re going against tradition, you can’t just willy-nilly do whatever. You need to create a counter-craft (as Bresson, Brakhage, Ozu, and others showed us). Reviewers, in their urge to thump out quick judgments, often don’t address craft practice directly. So if we simply talk of the Coens’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs as a grim, occasionally grotesque and zany take on Western conventions, we’re apt to take for granted just what a trim, absorbing piece of sheer filmmaking it is.

It’s worth attuning ourselves to what Adam Gopnik called his collection of Robert Hughes’ writings: The Spectacle of Skill. Paying attention to that enhances our appreciation for what filmmakers accomplish, and maybe it can nudge aspiring filmmakers to consider things to try.

So, herewith a quick analysis of the very beginning of the film’s second episode. The whole piece is not as audacious as the title episode, and not as poignant as “Meal Ticket” or “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It’s more of a light interlude. But we shouldn’t let its shaggy-dog payoff (“Your first time?”) make us think there’s anything slapdash about it.

There follow spoilers.

All the meanness in the Used-To-Be

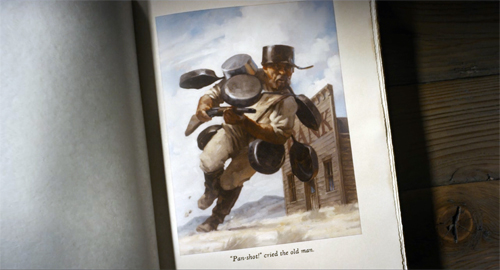

In the book that frames each tale, this one is called “Near Algodones.” As in the other episodes, an illustration prepares us for something we’ll see in the scene. The caption reads: “Pan-shot!” cried the old man.

Lesson 1: Make everything clear and simple, except what you want to suppress.

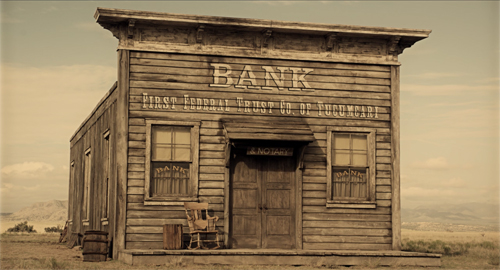

A master shot gives us the elemental situation: A bank, a well, and a lone rider with his horse.

These are the central components of the sequence. The isolation of the bank makes it a plausible target for a holdup. The geography will become important in the second stretch of the scene, while the well will provide cover to the Cowboy. His horse will prove notably reluctant to move.

Lesson 2: Attach the narration to a single character.

Throughout this episode, we’re “with” the Cowboy, not always through exact optical POV but more generally: our range of knowledge of the unfolding situation approximates his. This sort of restriction arouses curiosity (what’s going on in the bank?), as well as suspense and surprise (as we’ll see).

Lesson 3: Motivate new shots by offscreen sound.

Attachment to the Cowboy is reinforced by the play of his attention. Over the Leone-esque close-up we hear a creak. This motivates a cut to the bank’s hanging sign. As we hear a thump, he shifts his eyes; we see it’s caused by the bucket bumping against the well.

Lesson 4: Delay when you can.

Attachment doesn’t mean immersion. Instead of a shot from the Cowboy’s POV as he’s entering the bank, we get him pausing to size up the scene.

Only then do we get a shot of the bare bank and the teller’s windows, which (thanks to a wide-angle lens) seem impossibly far away.

Lesson 5: Let expectations go to work.

The holdup scenario, a convention of Westerns, is surely hovering in many viewer’s minds. When the Cowboy advances, we wait to see if our expectations pay off. You get suspense simply by having your actor move forward; what could be more economical?

Lesson 6: Prepare for later shots.

The tracking shot of the Cowboy’s boots and spurs might seem mere decoration, but it further delays his arrival at the window and sets up an important shot to come.

Lesson 7: Scale your shots according to the information they present.

Reverse shots are the workhorses of mainstream storytelling cinema. They are vehicles for character interaction, either based in dialogue or just the exchange of glances. The over-the-shoulder (OTS) version specifies the spaces the characters occupy, typically in a conversation. OTS framings also serve as a transition to closer views. Here the Cowboy’s goal in the scene is to learn how fortified the bank is against robbery.

After the opening stretch of purely visual storytelling, dialogue takes over. For us to grasp it better, the OTS framings give way to singles, which enlarge the teller’s performance and the Cowboy’s reactions.

The geezer’s chatter joins the motif of flowery monologues and eloquent bafflegab we’ll encounter throughout the film. The framing also lets us enjoy the performance, which suggests that this scatterbrain might be an easy mark. He does, however, mention that he has put down one attempted robber and “shredded the legs” of another.

The climax of the exchange is the Cowboy’s drawing his pistol and the teller’s explanation that he has to stoop to get “the large denominations.” The result is more shot-scale calibration: We need a single to see the gun looming (an OTS wouldn’t be as punchy), but the reverse shot can be OTS because we need to see how the teller’s stooping maneuver is concealed from the Cowboy. We are still attached to him and what he knows–or doesn’t know.

Another benefit: as variants of framings we’ve seen before, these let us quickly grasp what’s new in them (brandishing the pistol, ducking down).

Lesson 8: Use a cut, a crisp gesture, or a discrete sound to arrest attention.

Actually, the next shot does all three. The Cowboy tries to peer over the till, and a shot shows him taking a step forward as we hear a click. This framing pays off the shot of striding boots we saw in Lesson 6.

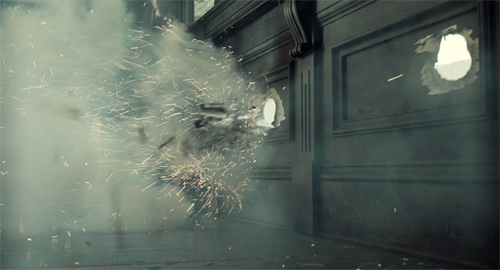

Within the same shot, the front of the teller’s window is blasted open. The Cowboy jumps sideways as another hole explodes, then another.

We’re back to visual storytelling. Now we understand why the teller has “shredded the legs” of another would-be robber. When the debris clears, a camera tilt shows that the Cowboy has sprung to the counter.

A mini-spectacle of skill: Handling the three blasts and the Cowboy’s evasion in a single percussive shot.

Lesson 9: Stagger the reveals.

Alexander Payne once remarked: “Whenever you can do a reveal, do it.” Here we have a suite of reveals, but they’re handled in a simple, cogent way.

When the Cowboy crouches on the counter, we have several questions. Is the teller going to fight? What created the blasts? And will the Cowboy get to the money?

These questions are answered, purely pictorially, in the shots to come. First, from his perch the Cowboy sees the partly open door. The teller has escaped, but because we’re restricted to the Cowboy’s perspective, we don’t know where he’s gone.

Just as one concise shot showed us the gunblasts and the Cowboy’s leap to the counter, now his descent and landing, followed in a single tilt, reveals the teller’s infernal machine: a row of shotguns poised to fire.

Another director would have devoted a POV shot to this revelation, but here it’s provided without fuss or forcing, as we follow the Cowboy’s crouch. He barely reacts and smoothly sets about finding the money. He grabs it in a single crisp close-up. And another cut takes us to the doorway, as the Cowboy hopes a view outside will reveal where the teller has gone.

Once more a POV is recruited, but it shows how much our protagonist doesn’t know.

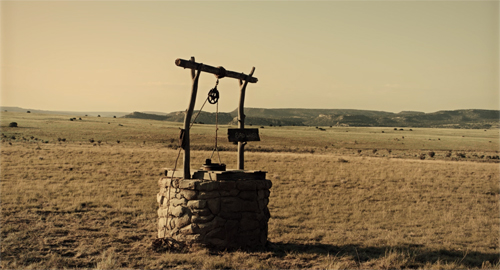

The elements we were given at the start–bank, well, horse–are laid out again, from the opposite angle. Thanks to the clarity of presentation, we fully understand that the old teller is hiding somewhere (probably with his lauded scattergun) and the Cowboy has to make a run for it. But to where?

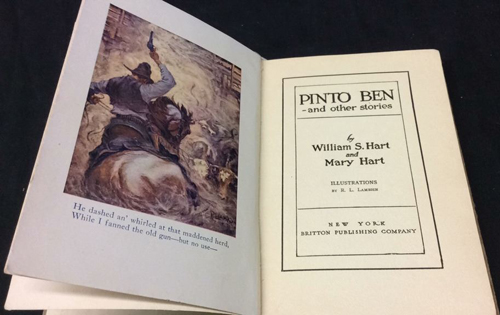

There are other things to talk about here, such as the homages to Leone (the mention of Tucumcari from For a Few Dollars More, the creaking of the sign recalling Once Upon a Time in the West‘s operatic opening). Perhaps the device of the book owes something to William S. and Mary Hart’s Pinto Ben (1919).

But we’re so used to considering the Coens pasticheurs that these allusions don’t interest me as much as the compact finesse of their style.

The rest of this scene will depend on reworking the narrative, auditory, and pictorial elements we’ve already encountered. You could go through that, and indeed the rest of the film, and trace the artisanal precision on display. (Let alone the sheer boldness of certain depth shots.) And the Coens are expert at using visual ideas for humor, as in the later scene when the Cowboy’s horse, browsing for more grass to nibble, stretches his noose-rope to the limit (see top image).

But I think I’ve said enough to indicate how rich an apparently straightforward handling can be. When we speak of careful pacing; when we think of building a scene; when we think of a movie that’s easy and graceful to follow, what Otis Ferguson called “a smooth clear line”–this is what we’re talking about.

There’s plenty of spectacle here, what with landscapes and gun blasts, but there’s another sort of spectacle as well: the quiet virtuosity of craft. You don’t see it that often these days, so when we encounter it, we should acknowledge it.

For another study of the Coens’ technique, see Jim Emerson on No Country for Old Men.

Other blog entries celebrate this sort of precision. See, for example, this analysis of Panic in the Streets, or the mind-boggling visual engineering of Fritz Lang (here and here). Otis Ferguson’s ideas about smooth cinematic storytelling are discussed in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

My first impressions of Scruggs, after seeing a magnificent big-screen presentation in Venice, are here. Netflix and Annapurna are to be congratulated for backing this movie, but it really deserves a wider theatrical release than it got. At least, please give us a Blu-Ray!

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).