Archive for May 2019

Could Hollywood possibly be in a box-office slump? Yet again?

Kristin here:

Speculative articles are presumably a lot cheaper for a news publication to run than are those pieces that involve travel, time-consuming research, and tracking down experts to weigh in on important events. The reporter need just sit at a computer, look at whatever evidence is at hand or a phone-call away, and opine on what one might expect to happen in the future. In part, of course, the opinion will be based on what happened in the past. The question is, what sort of information from the past would be most helpful in speculating with some likelihood of being right.

Not that it matters too much, since it’s pretty rare that months after events happen anyone goes back and checks on predictions made about them. That goes for prognosticators of award winners and of future hits and flops.

What might happen?

Facebook profile image for The Numbers research service

In this era of shrinking news media and burgeoning everything-else media, speculation has run rampant. It sustains the 24-hour news channels between breaking stories and a lot of print publications as well. Politics can generation all sorts of guesses and opinions, especially now, since there are so many players who can’t be expected to behave rationally. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter (both of which have advertising-supporting online versions) were once full of useful, hard-news articles that we film historians could snip and file away for, oh, say, cyclical revisions of a film-history textbook. Now David and I still subscribe to both and consider ourselves lucky if an issue has one or two truly informative pieces.

Not that these venerable publications are overwhelmingly full of speculative pieces. There’s the gossip, the real-estate section, the fashion section, the ten or twenty-five or one hundred most-powerful [fill in the blank] in show business, and so on.

But speculation seems to dominate in trade journals devoted to entertainment and film. There are obviously the predictions for Oscars and Emmys and other awards, which have become a year-round occupation. (The Oscars were given out in February, and almost ever since we’ve been getting lists of possible nominees for 2019, many for films not coming out for months.) Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other trades indulge in awards-prediction coverage far more extensively than they used to, since it presumably extends the period during which film studios and distributors take out expensive “For your consideration” ads.

Box-office trends are often interesting and even useful to read after the fact, in the year-end analyses. They are, however, pretty vapid when presented piecemeal, month by month. There are a great many clichés that writers trying to fill page-inches with speculation can treat as if they are news. One particularly persistent and illogical one is that the industry must be in a slump when total grosses go down after a record-breaking year. We’re now at that stage in 2019 when enough films have come out to allow comparison with last year’s figures by this date.

Pamela McClintock recently wrote such an article for The Hollywood Reporter: “Will Red-Hot Avengers Blaze the Path to a Sizzling Summer?” in the April 30 print edition, and, with the strange habit that these trade papers have of changing articles’ titles for the online version, “‘Avengers: Endgame’ Will Need More Help to Save Summer Box Office”. Just after Avengers: Endgame opened, McClintock wrote that

North American revenue is still down 13.3 percent year-over-year during the January-to-April corridor, throwing cold water on predictions that 2019 could eclipse the best-ever $11.9 billion of 2018. (Before Disney’s Endgame unfurled April 26, revenue year-to-date was running nearly 17 percent behind last year, its lowest clip in at least six years.)

Nonetheless, analysts remain cautiously optimistic that Hollywood can at least match, if not best, 2018’s mark by Dec. 31, with predictions for the global haul settling a new benchmark of north of $41 billion.

These predictions are based on optimism about the plethora of upcoming sequel items and reboots: Aladdin, The Lion King, Toy Story 4, The Secret Life of Pets 2, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Spider-Man, and Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Let me point out three things.

First, in virtually all cases of year-to-year comparison are based on dollars unadjusted for inflation. Inflation is different in different countries, so trying to achieve a total global figure for any given year would involve a separate calculation for every country where movies are shown—which is close to, if not totally, impossible to do. Adjusted figures are helpful for some purposes, especially for comparing domestic grosses within the USA. For example, virtually everyone was claiming that the three Hobbit films outgrossed the original three Lord of the Rings films. In adjusted dollars, though, LotR is still the champ.

Here’s a helpful hint. Box Office Mojo has an inflation adjuster in its upper-right corner. If someone were to want to compare the domestic gross of Avengers: Endgame to that of some older film, say, Avatar, it would be informative to use the figure shown below instead of, or at least alongside, its gross in 2009 dollars: $749,766,139. (All figures in this entry stated to be in adjusted dollars were done using this feature, and all charts are from BoxOffice Mojo as well.)

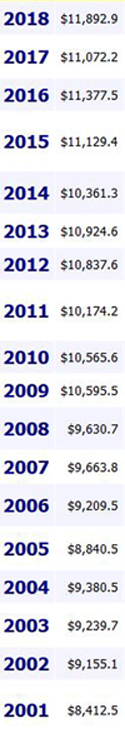

Seeing film grosses go up year after year can give the impression that the industry can go on expanding its earnings forever. Even after a record year like 2002 or 2009 or 2018, pundits seem to assume a slump if the following year sees lower box-office results. But every year can’t be a record year (except in movie executives’ dreams). The list at the left gives the total domestic gross of each year from 2001 to 2018 in millions of unadjusted dollars. Part of the rise is due to inflation. Part of it comes from ticket prices  being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

Second, usually a very few high-grossing films determine when there are record years. Avatar was the big film of 2009–but it had some help. More on this below.

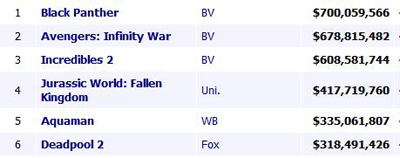

Third, those high-grossing films are usually released in the summer and in the Thanksgiving-Christmas seasons. True, that cycle is breaking down in the current attempts by studios to avoid releasing the biggest films opposite or even near each other. Black Panther, the top grossing film of 2018, came out in February 16. The studio probably didn’t expect it to do as well as it did, but the very fact that a traditionally “summer”-type film came out that early and topped the charts will just reinforce the industry decision-makers’ believe that there can be big hits at any time of year.

The point, though, is that if really big films come out late in the year, their grosses earned after the New Year are counted for the following year’s total. So for example, Avatar came out on December 18, 2009, and well over half of its domestic earnings came in 2010: $466,141,929 out of the $749,766,139 total. As the list shows, total domestic earnings across the industry jumped by close to a billion dollars between 2008 and 2009, but there was almost no decline in 2010, partly because all but the first two weeks of Avatar’s run came then and partly because Toy Story 3 came out. As for 2009, it may have been the year of (two weeks of) Avatar, but it was also the year of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, and The Twilight Saga: Full Moon.

Thus in talking about record BO years and why they happened, it helps to look at when the top earners of the previous year were released.

Take another example, 2002, which for years was considered the target to shoot for when it came to setting new records for grosses. That was the first year that the domestic gross was over $8 billion, and 2001 had been the first year over $7 billion.

The year 2002 was cited as the benchmark for the industry because it had four really major films come out–a relatively rare event, or at least it was then. Three of them were from some of the top franchises of all time, and one established what is now the top franchise of all time: Spider-Man, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

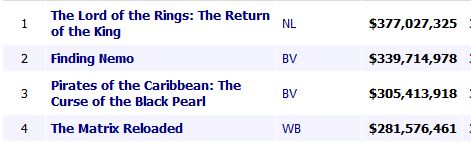

The last two titles were released on December 19 and November 15, so they helped make the 2003 total even slightly higher than the 2002 one—helped out by the top four of that year: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Finding Nemo (is Pixar itself a franchise?), Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, and The Matrix Reloaded.

In fact, no year between 2002 and 2009 went below the 2002 gross except 2005. In 2003, three films had grossed over $300 million domestically (below right), while in 2005 only one, Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Beyond that, however, was the fact that there was relatively little continuing box-office income being generated by 2004 films in early 2005. The top three films had all been released early in 2004: Shrek (May 19), Spider-Man 2 (June 30), and The Passion of the Christ (Feb 25). The number four film, Meet the Fockers (Dec 22), contributed a healthy $103,501,600 to the 2005 grosses, but number five, The Incredibles (Nov 5) was largely played out by the end of 2004 and gave only $8,760,254 to the 2005 total.

Consider the calendar

I’m not going to say whether 2019’s gross domestic box office will surpass that of 2018, because it doesn’t matter that much. Annual figures fluctuate but have been remarkably steady over the years (adjusting for inflation). The industry will make a lot of money as a whole, and Disney will do extremely well. There will be the occasional modestly budgeted film that becomes a hit. Every year has its A Quiet Place or Crazy Rich Asians, numbers 16 and 17 among box-office leaders last year.

I can, however, point out some relevant contributing factors.

First, as in 2005, there’s an unusually small amount of money carried over from films released late last year and still playing early into 2019.

The top four films for 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom all came out in the summer or earlier. The fifth, Aquaman, is the exception,  released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

Given this rare disadvantage, can this year’s blockbusters make up the difference and match or top 2018’s total grosses? Let’s do what Box Office Mojo does: look at what the last film of the franchises made. Let’s do that in adjusted 2019 dollars.

I should note that now more big tentpole films are grossing a very large amount of the total box-office. The three top films that helped create last year’s record made over $600 million domestically: Black Panther at $700.1 million, Avengers: Infinity War at $678.8 million, and Incredibles 2 at $608.6 million. Compare this to the 2003 chart above, where the top earners were making in the $300+ million range. That shift can’t be wholly accounted for by inflation, which isn’t that high.

How many films this year can do that, or at least get over $500 million? Even as I post this, Avengers: Endgame is hovering on the brink of passing $800 million. How about Toy Story 4 (which deserves to, if only for its incredibly clever and funny trailers)? Toy Story 3 made, in 2019 dollars, $480.6 million. Beauty and the Beast made $511.8 million, and The Jungle Book $375.8 million. Disney has two of these remakes coming out this year, Aladdin and especially The Lion King. These three seem the likeliest possibilities.

Beyond that, The Secret Life of Pets made $389.0 in 2019 dollars. On the lower side, The Fate of the Furious made $227.5 and Godzilla $217.2.

The weirdest thing about the current speculation is that the prognosticators aren’t even talking about the entire year. Despite McClintock’s mention of total grosses for 2019 at least matching those of 2018 by December 31, the latest film that she mentions is Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbes & Shaw, due out August 2. But why are we worrying about a slump when it’s plausible that just the films released up to that point could by themselves bring the total at least close to last year’s? We’re witnessing a film that will make as much as two ordinary blockbusters and possibly become the top grosser of all time (in unadjusted dollars, at least). We’ve already seen one low-budget film become a hit. Us grossed $174,580,800–oddly enough, very close to the total for Crazy Rich Asians, which did the same last year. As I’ve suggested, we could anticipate at least two or three summer blockbusters grossing in the $500-600 million range.

But more importantly, there are, after all, films to come after August 2. Big films. Most notably, Frozen 2 on November 22. Frozen made $441.8 in adjusted dollars. There’s the untitled Jumanji sequel; the previous Jumanji entry made $404,515,480. (The BoxOffice Mojo adjuster isn’t adjusting 2017 or 2018 to 2019 dollars yet.) There’s Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The last Star Wars movie, Solo, was an exception to the saga’s fortunes, making only $213,767,512; so let’s take the previous one, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which made $620,181,382 domestically. Beyond these there is a bunch of somewhat more modest sequels (Terminator: Dark Fate, It Chapter Two), as well as some potentially big stand-alones (Cats, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Rocketman). I personally am rooting for Jojo Rabbit (below) to become an unexpected hit. We’ll see.

The lack of attention to films coming out late in the year does make some sense. Right now the industry is concerned to promote its summer films. That’s what marketing people want to talk about with trade-media journalists. November is a long way off. Plenty of time to start speculating about holiday box-office and the awards season come August.

All in all, taking the factors that I’ve laid out into account, it looks like a pretty safe year for Hollywood. I can’t quite help feeling that the hand-wringing over this putative slump just makes for a more dramatic story than one declaring that the 2019 box office is doing fine, thanks. Of course, it’s especially fine for Disney. The heads of other studios might be doing some justifiable hand-wringing.

Update, July 3, 2019: Now we’re into the summer season, and the pundits are still worried because this year hasn’t caught up with last year, where the high-grossing films came earlier in the year than usual. That said, I tried watching The Secret Life of Pets 2 on a transatlantic flight and was so bored I turned it off after about half an hour. That part of Rebecca Rubin and Brent Lang’s Variety article I can believe.

David has written an entry about a related ongoing trope in trade-journal coverage of the movie business. The box-office coverage during “slumps,” real or imagined, often gets linked to the “death of cinema” notion, which David discusses here.

Jojo Rabbit.

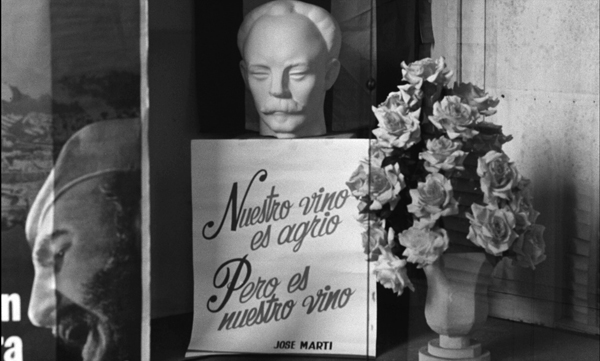

Politics and subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on the Criterion Channel

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Jeff Smith here:

Early last week, the Criterion Channel posted the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art.” It was my turn at the plate with a video essay on Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. The film has long been a personal favorite due to its formal and political complexity. If the aphorism “the personal is political” rings true for you, then you owe it yourself to watch Memories of Underdevelopment. It is a post-revolutionary culture’s most fully realized depictions of the survival of apre-revolutionary mentality.

A Third Way for Third Cinema

Hour of the Furnaces (1968).

“Toward a Third Cinema,” the 1969 manifesto written by filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, remains an important touchstone in the history of global film culture. It captures the militant spirit that characterized post-colonial activism in the late sixties and early seventies. At one point, Solanas and Getino describe the camera as an “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons” and the projector as a “gun that can shoot 24 frames per second…” (For the record, that less than a quarter of the speed of an M134 MInigun, which fires at a rate of 100 rounds per second.)

As advocates for the vital role guerrilla filmmaking could play in anti-imperialist struggles, Solanas and Gettino explicitly opposed “third cinema” to more established modes of film production. Of course, the big enemy was Hollywood. It represented a form of commercial cinema that was inextricably linked to the ideology of American capitalism.

More surprisingly, though, Solanas and Getino also condemned European art cinema and its attendant emphasis on individual personal expression. Although art cinema represented a step forward in terms of its attempt to create a non-standard language, it remained “trapped inside the fortress” in Jean-Luc Godard’s words. For Solanas and Getino, the French New Wave and Brazil’s Cinema Novo opened up new aesthetic possibilities. They offered the brio and rebelliousness of youth, yet fit neatly into established commercial distribution networks as the “angry wing” of a capitalist, bourgeois society.

Solanas and Getino practiced what they preached, however. Their ambitious 4-hour agit-prop documentary The Hour of the Furnaces remains a prototype of third cinema practice. The film is a collage of contrasting images and sounds. These juxtapositions often involve the kinds of associational editing and montage principles that Soviet directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein used in their work. At one point, Solanas and Gettino intercut cattle and sheep being slaughtered on the killing floor of a meatpacking plant with ads for various products originating in Western capitalist societies. (See below and above.)

The comparison was about as subtle as the sledgehammer used to kill the cattle. But the message was clear. The global success of American products, like Chevrolets, depended upon the violent suppression of “underdeveloped” populations.

Memories of Underdevelopment’s critique of post-colonialism is no less incisive, but it’s much less didactic. At first blush, Alea’s film seems to be the kind of European-influenced art cinema that Solanas and Getino explicitly reject. Indeed, Alea even self-consciously gestures toward this tradition through his explicit citation of French New Wave films, like Hiroshima Mon Amour. These allusions are reminiscent of the kinds of cinematic quotations that Godard and Francois Truffaut embedded in their own films.

Moreover, Alea also creates the kind of depth of narration in Memories of Underdevelopment that became strongly associated with art cinema’s emphasis on subjective realism. Throughout the film, Sergio’s thoughts and feelings on the current state of Cuba are given to us via voiceover narration. Many of Sergio’s observations function as ongoing commentary on the symptoms of “underdevelopment” that define contemporary Cuban society. For instance, over shots of downtown shops and boutiques, Sergio notes that Havana is often called the “Paris of the Caribbean.”

Such a descriptor seems a double-edged sword. The comparison to Paris is a way of praising the vibrancy of Havana’s cultural life, its bookstores, museums, cinemas, and modern department stores. Yet the qualification “…of the Caribbean” highlights its isolation from true taste-makers and fashionistas in New York, London, and Paris. For anyone who doesn’t live there, Havana is, at best, a playground for rich tourists from Europe and America.

As a member of the Cuban intelligentsia, Sergio often seems an unusually perceptive social critic. Yet Alea’s creation of such a strong alignment with Sergio seems designed to test the viewer’s moral and political allegiance. As a repository of pre-revolutionary attitudes, Alea’s characterization of Sergio encourages us to ask why Havana should aspire to be Paris in the first place. In a society that seeks to eliminate class distinction, why would one strive for such elitism no matter how rich and storied its culture may be?

In employing a device that often fosters sympathetic engagement with characters, is Alea just as “trapped inside the fortress” as French New Wave directors are? Actually, Alea also seems determined to turn the purpose of character alignment on its head.

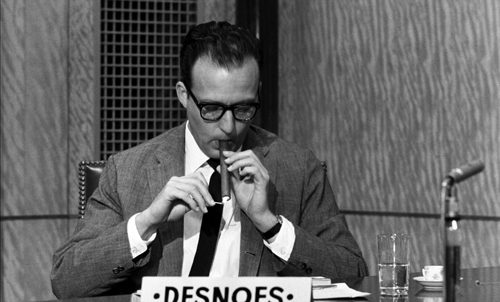

As an intellectual, Sergio possesses a great understanding of Cuba’s relation to the rest of the world, but he seems determined to ask the wrong questions about its future. Therein lies the character’s great tragedy. As novelist Edmundo Desnoes observes, “His irony, his intelligence, is a defense mechanism which prevents him from being involved in the reality.” There is no place outside the palace gates for those like Sergio. Yet in probing his place “inside the fortress” Alea also shows how it rots from within.

By turning the camera’s gaze inward, Alea navigates a path between the agit-prop documentary of Solanas and Getino and the formal adventurousness of an art cinema director like Chile’s Raúl Ruiz. He set out to examine the vestiges of bourgeois thinking in Castro’s Cuba, using Sergio as a “litmus test” for Cuban audience’s political sensibilities. If you find yourself sympathizing with Sergio, seeing him as a victim of the revolution…. Well, then you better check yourself before you wreck yourself. In posing such a challenge, Alea pulls off a pretty neat trick. He manages to create a “third way” in third cinema by merging the polemical aims of agit-prop with devices and formal structures of the art film.

The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cad

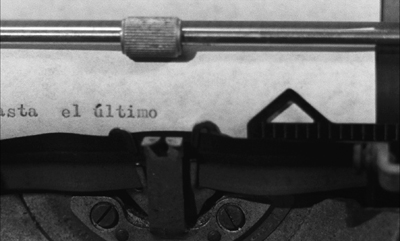

In a gesture that displays both self-consciousness and hubris, Edmundo Desnoes, the author of the novel that served as the source of the film, cast his hero as a writer. Although Alea changed much of Desnoes’ original story, this one small detail was something he preserved in his adaptation of the book. Indeed, just after Sergio has said goodbye to his wife and parents at the airport, we see him sitting at a typewriter. The sentence he writes – “All those who have loved and fucked me over up to the last moment have already gone.” – indicates both his anger in the moment and that his writing has more than a trace of autobiography.

Sergio’s status as a writer encourages the viewer to see him as a surrogate for both Desnoes and Alea. This possibility is even reinforced in a scene where Sergio attends a roundtable discussion of “Literature and Underdevelopment” where Desnoes is featured as one of the panelists.

If Sergio truly is a surrogate for the filmmakers, then Alea shows some real guts in centering his film on an alter ego that is both politically reactionary and sexually predatory.

It is a mark of the film’s complexity that Sergio has certain very attractive traits even though he emerges as a thoroughly unlikeable cad. He is smart, cultured, and good-looking, for example. But he is also passive, cynical, and snobbish.

The dimension of Memories of Underdevelopment, however, that most clearly reveals Sergio’s corruption and moral rot involves his various relationships with women. Alea develops this idea throughout the film in terms of a Pygmalion motif: Sergio seeks to remake his romantic partners in the image of his first love, a German girl named Hanna.

In flashbacks, we learn that Sergio taught his first wife how to talk and dress, how to approximate a downmarket version of European elegance. Similarly, when Sergio initiates a romance with Elena, we see him taking her to bookstores and museums, trying to instill in her some appreciation for art and literature.

Sergios’ European ideals even pervade his sexual fantasies. After looking at an image of Botticelli’s Venus, Sergio imagines his housekeeper, Noemi, lying naked on his bed in a similar pose.

Similarly, when Noemi describes her Christian baptism to Sergio, he imagines it in images that seem culled from a hack romance novel. They embrace in a swoon, with their eyes locked, all wet clinging fabric and raging hormones.

Shot in slow motion, the episode is also accompanied by Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, a concert piece so familiar to most audiences that its inclusion borders on cliché.

It would be one thing, however, if Sergio’s sexual peccadilloes remained in the realm of harmless fantasy. More often than not, Alea depicts Sergio’s relations with women as episodes of exploitation and mental cruelty. A flashback to Sergio’s adolescence implies that the psychological roots of this misogyny lies in his first sexual experience as he and a school chum visit a brothel.

The transactional nature of the encounter is replicated in Sergio’s relationships later in life. After Sergio splits with Hanna, he marries Laura and is given a cushy job in the family business. He also lures Elena up to his penthouse with the promise of his ex-wife’s old clothes. In each instance, Sergio’s sexual or romantic relations with women are based on some notion of recompense: cold hard cash with the prostitute, the reward of a job with his wife, and haute couture with Elena, his new conquest.

As before, the exploitative undertones of Sergio’s relationships with women are reinforced by the film’s style. Sergio’s initial meeting with Elena is handled in a series of long tracking shots representing his optical point of view.

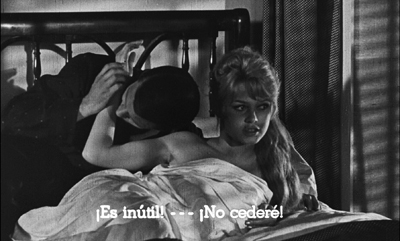

With his creepy pickup line, Sergio seems more of a stalker than a paramour. The troubling implications of this first encounter become more explicit midway through the film when Sergio literally chases Elena around his bedroom. The narrative rhyme with the earlier scene is made evident in Alea’s mobile long take, which once again represents Sergio’s visual perspective. Elena flirts coquettishly, sticking out her tongue at the camera.

But her discomfort in the situation becomes evident in her attempts to rebuff Sergio’s advances. Like the film’s use of voice-over, the moving pov shots spatially align the viewer with Alea’s unlikeable protagonist even as it implicates the audience in his victimization of Elena.

Later, when Sergio is put on trial for sexually assaulting Elena, he becomes the object of the camera’s unrelenting look along with the other petitioners. Here Alea uses a variant of the previous style. The longish takes remain. But where the previous shots used movement to suggest Sergio’s brazen advances toward Elena, the camera’s stasis within the courtroom reflects the perspective of the tribunal hearing the case. Alea cuts quite freely around the space. Still, he always returns to static close-ups of Sergio, Elena, her mother, her father, and her brother as they respond to the questions of offscreen interlocutors.

The scene proves to be the biggest challenge to the viewer’s allegiance with Sergio. He affects the demeanor of someone wrongfully accused. Yet, although the act itself is elided, Elena’s protestations beforehand and her tears afterward suggest that Sergio is probably guilty of the crimes for which he is accused. His voice-over, however, reveals his resentment toward the entire proceedings. The matter of his guilt or innocence is immaterial. What truly angers Sergio is the fact that someone of his lofty station endures treatment more suited to a common crook. He claims that he would never have faced charges during the Batista era. Sergio blames his ordeal on Cuba’s new political landscape. The judgment of his actions is more a matter of proletarian revenge rather than anything he has done.

It is easy to imagine some viewers feeling a pang of sympathy for Sergio. Jurisprudence often includes the presumption of innocence and Alea’s handling of the incident with Elena is ambiguous enough to have certain doubts. Moreover, Sergio has been impoverished by the government’s seizure of his property, something that makes his anger at Elena and her family seem more reasonable.

But what is especially striking in Sergio’s voice-over is the sense of entitlement he displays based on his previous social position. Alea seems to count on the fact that Cuban audiences in 1968 will recognize Sergio’s condescension as a symptom of pre-revolutionary ideology. His previous wealth, his education and culture, his status as an artist all sanction his satisfaction of his desires, even if that means taking the virginity of an 18-year old girl. In his characterization of Sergio, Alea not only reflects the broader influence of the French New Wave. He also revives a classic character type of French literature and cinema: the Parisian roué.

Mr. Schwitters Meets Mr. Alea: Mixing Modalities in Memories

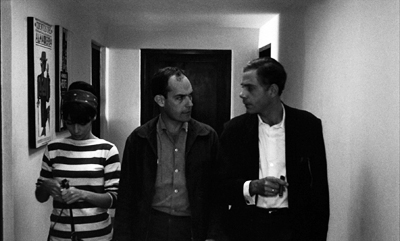

The most oft-quoted line in Memories of Underdevelopment is not something said by Sergio, Elena, or even Sergio’s brusque friend, Pablo. Instead it is uttered by Alea in a director cameo. He appears in a scene where Elena performs in a screen test at ICAIC, Cuba’s central institute of film production. Alea (center, below) shows Sergio and Elena some of his work in progress, saying, “It’s a collage. A bit of this and a bit of that.”

Most critics have noted both the self-consciousness of the moment and its layers of meaning. The footage that Alea screens is made up of scenes cut out by Cuban censors under the Batista regime. It offers a fairly dismal portrait of Cuban film history as something mostly comprised of titles imported from other colonial empires, like the Brigitte Bardot vehicle Une parisienne. This is precisely the kind of cinematic legacy that Alea and other Third Cinema directors set out to counter.

Alea’s description of his film as a collage also has been interpreted as a clue as to how one should view Memories of Underdevelopment itself. More specifically, his comment captures some sense of the film’s complex visual texture, its mix of still photographs, television clips, newspaper headlines, and even comic strip panels.

It also describes the way Alea embeds documentary footage within his portrait of Sergio as a disaffected intellectual. To some extent, this strategy is simply a continuation of Alea’s digressive approach to narration. These interpolated documentary passages fit a larger scheme that also shows fragments of Sergio’s consciousness in fleeting fantasy images and elliptical flashback sequences. Yet these segments of Memories of Underdevelopment also sharpen its political edge. In effect, Alea injects the agit-prop spirit of The Hours of the Furnaces into his “second cinema” character study.

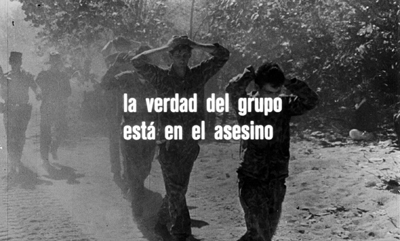

Consider the segment entitled “The Truth of the Group is in the Murderer.”

It is motivated as Sergio’s description to Pablo of the book he is currently reading. But it uses photographs and newsreel footage to explore the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the system of political repression and torture that existed under Batista. The title hints at the larger ideological point of the sequence, namely that the regime’s institutional framework served as a means of displacing and shifting criminal culpability away from its individual members. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Sergio is implicated in this dialectical arrangement between the individual and the group insofar as each part of it gives meaning to the whole.

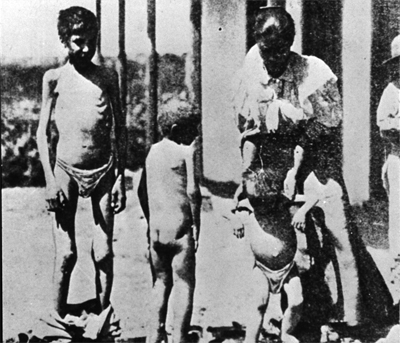

In a scene where Pablo gets his car ready for inventory, Sergio’s mind begins to wander. Alea then cuts to a series of still photos depicting hunger and starvation in Latin America.

In his voiceover, Sergio notes that the death toll from malnutrition exceeds the combat deaths of World War II. The sequence suggests Sergio’s insight into the problems of underdevelopment under capitalism. Alea’s imagery poignantly illustrates the disproportionate impact of such deprivations on society’s most vulnerable members, its children. This mini-documentary in Memories pointedly rebukes the colonialist regimes still present in Latin America by highlighting the cruel effects of such economic exploitation by First World powers.

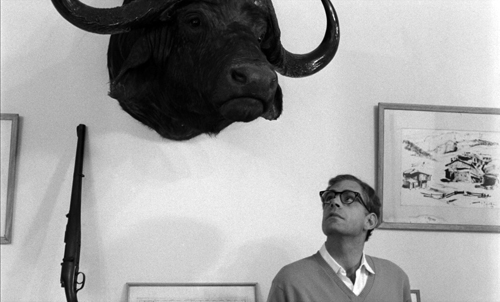

Similar sequences pop up in the episode labelled, “A Tropical Adventure.” The title refers to Sergio and Elena’s visit to Ernest Hemingway’s former home in Havana, which had been turned into a museum.

A series of photos shows Hemingway’s involvement in Spanish politics, particularly the civil war of the 1930s. A second series of photos depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his longtime servant Rene Villarreal. In his voiceover, Sergio hints that their master-servant relationship captured some of the vagaries of American imperialism. Sergio concludes that Hemingway must have been unbearable.

Sergio’s voice-over during these sequences offers one of the clearest statements of his character’s dualism. He conveys sympathy with Villarreal as a fellow Cuban and recognizes that Hemingway’s paternalism is itself an expression of colonialist ideology. Yet Sergio also seems to identify with Hemingway’s social position given his elite status as a rentier and aspiring writer. His trenchant observations about Hemingway’s relationship with his servant is an unwitting acknowledgement of how easily he could slip into the shoes of the great American author and adventurer.

In the battle for Sergio’s soul the “great white hunter” wins out as we see him hiding from Elena until she just gives up and walks away. Sergio’s condescending treatment of Elena is merely the flip side of the imperialist dialectic expressed by “the faithful servant and the great Lord. The colonialist and Gunga Din.”

Memories’ political sophistication largely derives from Alea’s sensitive treatment of his protagonist’s inner conflict. As a remnant of a previous historical moment, Sergio’s jaundiced perspective suggests that life under the Castro regime has simply substituted a new set of problems for life under the Batista regime. Indeed, for many viewers circa 1968, Alea’s look back at the era between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis might seem an endorsement of his hero’s nihilism and fatalism. Such was the case for several U.S. film critics who Alea disparaged later, claiming that their identification with Sergio caused them to mistakenly privilege the depiction of the artist’s self-interest over the needs of Revolution.

As Alea wrote more than a decade after Memories of Underdevelopment was released, “In Cuba, the Revolution is in power. This means that the conditions of struggle have changed.” Sergio’s struggle to find his place within post-Revolutionary Cuba becomes a metaphor for struggle itself. It is easy to celebrate the moment of triumph when a nation overthrows its oppressors. But a society’s problems don’t just disappear when you have regime change. Memories is the rare film that confronts the challenges faced in the aftermath of any revolution. It takes a hard look at the difficulties in remaking both a society and culture caught in the shadows of two global superpowers: the US and the USSR. In Alea himself put it:

It is to the spectator that the film should reveal the symptoms of possible contradictions and incongruities between good revolutionary intentions – in the abstract – and a spontaneous and unconscious adherence to certain – concrete – values belonging to bourgeois ideology.

Sergio simply becomes the vehicle through which Cuban audiences were encouraged to consciously grasp their own contradictions.

Alea’s insights here attest to his remarkable achievement in Memories of Underdevelopment. By exploring Cuba’s travails after Castro’s seizure of power, Alea knew that First World audiences might misinterpret the film. They might even use Memories to affirm their own imperialist identity. Yet this was not a design flaw. Instead, the film’s vulnerability would also turn out to be its greatest strength among domestic Cuban audiences. Alea’s use of cinematic devices to convey subjectivity imparts a simple but powerful lesson: the Revolution may be over, but revolutionary struggle never ends.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work. Also thanks to our colleague Erik Gunneson.

The text of “Toward a Third Cinema” is widely available on the Internet, as here.

The most useful resource for information on Memories of Underdevelopment remains the volume in Rutgers Films in Print series. The book contains a reproduction of the continuity script, a reprint of Edmund Desnoes’ original novella, contemporaneous reviews, and Alea’s own reflections on the film some twelve years after it was released.

The film was rereleased in 2018 after undergoing a 4k restoration. Reviews can be found here, here, here, and here. An interview with director Tomas Gutiérrez Alea can be found here. An excellent overview of Alea’s career in its entirety can be found here.

Here’s a complete listing of our Observations series on the Criterion Channel. Our installment on Hiroshima mon amour provides an intriguing comparison to this entry.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Some highlights of Venice appear at last

Sunset (2018).

Kristin here:

Going to the Venice International Film Festival in 2017 and 2018 has been a joy. Still, there’s a downside for our readers. We write about the films that premiere there in early September, but the films themselves appear months–sometimes many months–after the festival ends.

Of course, two titles, Roma and The Ballad of Buster Scrugges, appeared fairly soon on Netflix, and First Man had an October opening. After a delay, one of David’s recommended films, Dragged Across Concrete, had a quick, spotty theatrical release and is now available on several streaming platforms, as well as DVD and Blu-ray.

Two others of our Venice favorites are in narrow theatrical release only now, and we think you should seek them out.

The other Manson film to see this year

One film is Mary Harron’s Charlie Says, about the lead-up to and aftermath of the Manson killings. David wrote about it in a report on crime-related films at the festival. We both liked it very much, as a very original approach to the subject. Now Manohla Dargis has published an enthusiastic review, calling the film “powerful and deeply affecting.” Critics have split in their opinions, but we’re with Manohla on this one.

In all the complaints last year over Venice only having one female-directed film in competition, the many women whose films premiered in other threads were largely overlooked. I saw several of them, and I was very glad I put Harron’s film on my viewing schedule.

Seeking out Sunset

My favorite film from the festival was Lázló Nemes’s Sunset. Yes, I loved First Man, Roma, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, but Sunset was an instant classic, a film I wanted to see again while I was only a third of the way through the initial viewing.

Usually at festivals we have to include groups of films in each blog entry, even though they deserve more attention. In Sunset‘s case, I waited until I could see a screener and read the interviews with the filmmakers in the special Hungarian journal issue devoted to the film. I devoted a single analytical post to it (which links to an online version of that journal issue).

Without serious spoilers, since it’s a film of mystery and suspense, I tried to convey its unconventional approach to extremely restricted point of view and its brilliant camerawork and design. Many reviewers, however, have dismissed it as baffling or incomprehensible. I obviously disagree. It’s a challenging film, there’s no question about that. But aren’t there great artworks that are challenging in various ways? Works that mystified their original audiences? In order to appreciate them, don’t we expect that we’ll need to experience them more than once or twice? Of course, most reviewers don’t have that option before publishing their responses, but all the more reason to be cautious about condemning something because it’s thoroughly unconventional.

We looked forward to another chance to see Sunset on the big screen, and now it is in release. Its only local venue was at the AMC Classic Desert Star 15 just north of Baraboo, on the edge of the Wisconsin Dells. About 40 minutes of driving brought us to an impressive multiplex from 1999 with a desert theme. The Desert Star name comes from the fact that the theater is located in a much larger Kalihari entertainment complex, with indoor miniature golf, an amusement park with Ferris wheel, and other attractions. An odd venue, but a pleasant one.

For me, on third viewing, the film held up entirely, and I think I figured out a few of the things that had been unclear to me before. I’m sure another viewing will be illuminating as well, though there are clearly ambiguities that can never be resolved, intendedly so. David, seeing it for the second time, was even more impressed than at Venice.

Sunset is not coming out in the UK until May 31. Nemes himself is currently touring theaters showing the film on 35mm (schedule here). It was shot in 35mm and looked great on the huge screen of the Lido’s Sala Grande. Artificial Eye has announced that a Blu-ray will be released in the UK later this year.

Thanks as ever to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics for his help with this and our earlier entry.

AMC Classic Desert Star 15, Baraboo Wisconsin.

Accident forgiveness: J.J. Murphy’s REWRITING INDIE CINEMA

Maidstone (1970).

DB here:

Did you ever want to beat up Norman Mailer? The impulse must have flitted through the minds of many who paged through his work, saw him on TV, or encountered him swaying pugnaciously at a party. Rip Torn took the opportunity. One day in 1968, he whacked Mailer with a hammer and started to strangle him. As the distinguished author tried to bite off Torn’s ear, Mailer’s wife leaped into the fray and his children shrieked with fear.

This scene, totally unscripted, appears in Mailer’s film Maidstone (1970) and opens J. J. Murphy’s new book Rewriting Indie Cinema: Improvisation, Psychodrama, and the Screenplay. Nothing could better prepare us for his exploration of the traditions–and sometimes jarring consequences–of spontaneous performance in modern American movies.

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

At the same time, he was teaching both production and screenwriting. His books reflect his deepening interest in the creative process of making a film outside the Hollywood system. His initial study, Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work (2007), focused on the principles of screenplay construction that emerged with US indie cinema. Then, in The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012), J. J. offered the most complete analysis of this superb body of work. In the process, he opened up a new vein of exploration. The idea of psychodrama proved an exciting way of explaining the fascinating, awkward performances in films like Kitchen (1965), Vinyl (1965), and Bike Boy (1967).

Now the concept of psychodrama gets full play in an ambitious account of the changing role of improvisation in off-Hollywood cinema. What happens, J, J. asks, when filmmakers give up the screenplay? How do they construct a story, define characters, build performances? Rewriting Indie Cinema sweeps from the 1950s to recent films like The Rider and The Florida Project. By looking for alternatives to the fully prepared screenplay, it posits a fresh way of thinking about American film artistry.

Human life isn’t necessarily well-written

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968).

To start off, J. J. proposes that we think of improvisation in a systematic way. Of course, the concept can be treated broadly. Even Hitchcock, we learn from Bill Krohn, improvised on the set much more than he claimed. But J. J. suggests that improvisation can be considered as a basic creative concept, a founding choice for art-making.

In the 1950s, many American artists began to embrace chance, accident, and personal expression. Abstract Expressionism, bebop, the Judson Dance Theater, Robert Frank’s snapshot aesthetic, and other tendencies valued spontaneity as both authentic self-expression and a challenge to conformist culture. The idea of spontaneity was carried into cinema by Jonas Mekas and fueled what became the New American Cinema of John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, and other filmmakers.

But the idea had deeper sources in another trend that J. J. painstakingly brings to light. The Austrian theater director Jacob L. Moreno developed in the 1920s what he called the Theatre of Spontaneity (Das Stegreiftheater). Performances consisted of purely improvised dialogue. When Moreno emigrated to America, he founded “Impromptu Theatre” in the same vein. His 1931 performance at Carnegie Hall was greeted by the New York Times with some disdain:

The first play, like the ones that followed, turned out to be a dab of dialogue uneasily rendered by its hapless players. . . . It became more and more evident that heavy boredom, rather than “forms, moods and visions,” were [sic] the product of the actors. Demanding wit above all else, the Moreno players lacked that essential as fully as the premeditation upon which they frown so heartily. The legitimate theatre, it can be reported this morning, is just about where it was.

Of course improvisation had already proven its worth in vaudeville and in jazz and other musical idioms. Today versions of Moreno’s “spontaneous theatre” flourish in comedy clubs.

Before coming to America, Moreno had discovered that improvisation had therapeautic functions as well. When a couple enacted the frustrations of their marriage, the audience was moved and Moreno was convinced that this “psychodrama” harbored artistic possibilities. Moreno’s wife Zerka called psychodrama “a form of improvisational theatre of your own life.”

J. J. shows Moreno’s pervasive influence on the postwar American scene. Psychodrama became one trend in social psychology, used to help prisoners, narcotics addicts, and even business executives. Woody Allen, Arthur Miller, and other artists were aware of Moreno’s work as well.

Drawing on Moreno but recasting him for film-related purposes, J. J. proposes a spectrum of improvisational options. There’s the completely improvised, ad-lib option, seen in Maidstone and much of Warhol’s work. Here the performers just make it up as they go, though with minimal framing of a situation. Then there’s the possibility of “planned” improvisation, in which there’s a story outline and more or less pre-set scenes. Sean Baker’s Tangerine (2015), for example, was made from a seven-page treatment that included only a couple of lines of dialogue. Then there’s the “rehearsed” option, in which the players collaborate to prepare the scenes and develop the characters, workshop fashion. In production the performers mostly stick to the “script” they’ve created. J. J. points to the films of Cassavetes as a clear case.

Any given film can mix these options, so that some scenes are planned roughly while others are purely ad-lib. And a filmmaker can explore the spectrum across several films, as Joe Swanberg has done.

Where does psychodrama come in? J. J. shows that any of the three points on the improvisation spectrum–pure, planned, and rehearsed–can yield performances that are based in the actual mental states and personal histories of the players. In our Cinematheque screening devoted to his book, Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game (1993) served as an example. Harvey Keitel invested his character, an intransigent film director, with the still simmering emotions he felt after his breakup with Lorraine Bracco. Meanwhile Ferrara set up scenes that would provoke Madonna, playing Keitel’s actress, to break character and reveal her immediate responses.

Ferrara wanted to attack Madonna’s celebrity image, and J. J. reads the aftermath to a rape scene in the film being made as projecting the star’s own stammering outrage at having been exploited.

Throughout the book, when improvisation becomes psychodrama, fiction moves closer to documentary. The last chapter examines how certain films considered documentaries, like Robert Greene’s Actress (2014) and James Solomon’s The Witness (2015), cross over into psychodrama from the other side, so to speak.

A detailed study of William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) shows how Greaves used psychodramatic techniques to create an even more complicated film-within-a-film than Dangerous Game. Two characters, Freddie and Alice, are played by five different pairs of actors, with all their scenes recorded by a bevy of camera and sound staff.

Greaves also incorporates self-criticism. When crew members object to the script, another participant remarks: “Human life isn’t necessarily well-written, you know.”

Given these conceptual tools, J. J. goes on to trace the production methods employed by a wide range of filmmakers, from Morris Engel in The Little Fugitive (1953) and Cassavetes in Shadows (1959) to Mumblecore and after. Through a mixture of film analysis and background research, he brings to light a vast variety of creative options that can bypass fully-scripted cinema.

Rewriting the unwritten

Paranoid Park (2007).

J. J.’s survey of production methods is embedded in a new historical argument about the shape of off-Hollywood filmmaking. The New American Cinema of the 1950s, which Mekas called “plotless cinema,” was wedded to a sense of realism. But it operated within limits. Cassavetes serves as a benchmark: “I believe in improvising on the basis of the written work and not on undisciplined creativity.” By balancing the planned with the impromptu, his films allowed for the actors to surprise one another. At the same time, Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967) showed how psychodrama could pass easily into documentary, exemplifying Erving Goffman’s theory that everyone is playing theatrical roles in everyday life.

This open approach to screenwriting and screen acting was explored by many filmmakers in the 1960s and a little after: not only the well-known Warhol and Mailer but also Kent Mackenzie, Barbara Loden, William Greaves, and Charles Burnett. J. J. examines all this work in admirable detail. I was especially happy to see that he includes Jonas Mekas’ The Brig (1964), the harrowing film that showed me, in my undergrad days, what the New American Cinema could do in filming a play.

By the time Ferrara made Dangerous Game, most independent filmmaking had moved away from improvisation toward more tightly scripted expression. J.J. traces the institutional pressures operating here. The Sundance Film Festival and PBS’s American Playhouse favored fully-planned projects compatible with the Hollywood standard. The Sundance Institute, launched in 1981, explicitly aimed to correct what was considered the two faults of independent production: screenplays and performances.

The success of polished work like sex, lies, and videotape (1989) and Pulp Fiction (1994) created new norms for American indie cinema. Director-screenwriters like Soderbergh, Tarantino, David Lynch, Hal Hartley, Todd Haynes, the Coens, and Todd Solondz were models for younger filmmakers. As J. J. points out, their screenplays were often published as part of the marketing of the films. Framing the new trend as dominated by the screenplay helped me understand why Bryan Singer, Doug Liman, Karyn Kusama, and other indie filmmakers who came up in the wake of this generation moved so easily to mainstream genres and big-budget projects.

But history plays strange tricks. In the 2000s, filmmakers who felt constrained by the demands of tight scripting began to try something else. J. J. pays special attention to Gus Van Sant, who after proving his commercial craft, made some films with varying degrees of improvisation: Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), Last Days (2005), and Paranoid Park (2007). Some of the Mumblecore directors relied on screenplays, but the prolific Joe Swanberg adopted a free-form approach, to which J. J. devotes a chapter.

J. J. goes on to survey the work of Sean Baker, the Safdie brothers, Ronald Bronstein, and other directors who have revived the New American Cinema’s impulses in the digital age. He concludes:

Digital technology in effect, democratized the medium, allowing young filmmakers to revive cinematic realism precisely at a time when indie cinema was at risk of losing its identity. In the new century, the use of improvisation and psychodrama provided a sense of continuity with indie cinema’s roots.

J. J. retired from UW–Madison at the end of 2018, and last Saturday night he was honored at our annual screening of student projects. He has been a constant force for good in our department, and we owe him more than we can say. Among those debts is this outstanding contribution to US film studies.

The book’s title carries a double meaning. American independent cinema has been, at crucial periods, “rewritten” by filmmakers who relied on spontaneity rather than a cast-iron screenplay. At the same time, J. J.’s panoramic research in effect rewrites that history. I’m sure that other researchers will build on his wide-ranging arguments, which put the creativity of artists–filmmakers, performers–at the center of our concerns.

J. J.’s books join a cascade of recent work by other colleagues here at Wisconsin. This blog has highlighted Jeff Smith’s Film Criticism, the Cold War and the Blacklist (2014), Kelley Conway’s Agnès Varda (2015), Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound (2015), Lea’s and Ben Brewster’s enhanced e-book of Theatre to Cinema (2016), and Maria Belodubrovskya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin (2018).

P.S. 9 May 2018: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correction of a misspelled name!

Kelley Conway awards J. J. Murphy a gilded Badger at the Communication Arts Showcase, 4 May 2019.