Politics and subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on the Criterion Channel

Sunday | May 19, 2019 open printable version

open printable version

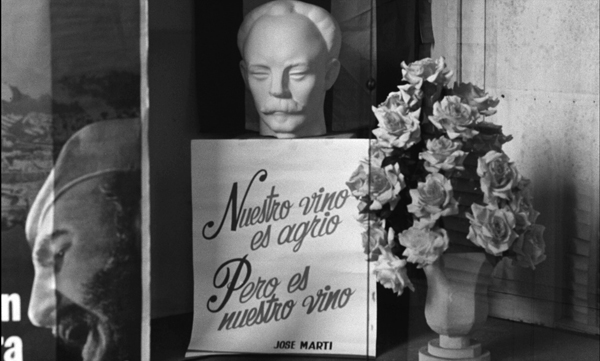

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Jeff Smith here:

Early last week, the Criterion Channel posted the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art.” It was my turn at the plate with a video essay on Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. The film has long been a personal favorite due to its formal and political complexity. If the aphorism “the personal is political” rings true for you, then you owe it yourself to watch Memories of Underdevelopment. It is a post-revolutionary culture’s most fully realized depictions of the survival of apre-revolutionary mentality.

A Third Way for Third Cinema

Hour of the Furnaces (1968).

“Toward a Third Cinema,” the 1969 manifesto written by filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, remains an important touchstone in the history of global film culture. It captures the militant spirit that characterized post-colonial activism in the late sixties and early seventies. At one point, Solanas and Getino describe the camera as an “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons” and the projector as a “gun that can shoot 24 frames per second…” (For the record, that less than a quarter of the speed of an M134 MInigun, which fires at a rate of 100 rounds per second.)

As advocates for the vital role guerrilla filmmaking could play in anti-imperialist struggles, Solanas and Gettino explicitly opposed “third cinema” to more established modes of film production. Of course, the big enemy was Hollywood. It represented a form of commercial cinema that was inextricably linked to the ideology of American capitalism.

More surprisingly, though, Solanas and Getino also condemned European art cinema and its attendant emphasis on individual personal expression. Although art cinema represented a step forward in terms of its attempt to create a non-standard language, it remained “trapped inside the fortress” in Jean-Luc Godard’s words. For Solanas and Getino, the French New Wave and Brazil’s Cinema Novo opened up new aesthetic possibilities. They offered the brio and rebelliousness of youth, yet fit neatly into established commercial distribution networks as the “angry wing” of a capitalist, bourgeois society.

Solanas and Getino practiced what they preached, however. Their ambitious 4-hour agit-prop documentary The Hour of the Furnaces remains a prototype of third cinema practice. The film is a collage of contrasting images and sounds. These juxtapositions often involve the kinds of associational editing and montage principles that Soviet directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein used in their work. At one point, Solanas and Gettino intercut cattle and sheep being slaughtered on the killing floor of a meatpacking plant with ads for various products originating in Western capitalist societies. (See below and above.)

The comparison was about as subtle as the sledgehammer used to kill the cattle. But the message was clear. The global success of American products, like Chevrolets, depended upon the violent suppression of “underdeveloped” populations.

Memories of Underdevelopment’s critique of post-colonialism is no less incisive, but it’s much less didactic. At first blush, Alea’s film seems to be the kind of European-influenced art cinema that Solanas and Getino explicitly reject. Indeed, Alea even self-consciously gestures toward this tradition through his explicit citation of French New Wave films, like Hiroshima Mon Amour. These allusions are reminiscent of the kinds of cinematic quotations that Godard and Francois Truffaut embedded in their own films.

Moreover, Alea also creates the kind of depth of narration in Memories of Underdevelopment that became strongly associated with art cinema’s emphasis on subjective realism. Throughout the film, Sergio’s thoughts and feelings on the current state of Cuba are given to us via voiceover narration. Many of Sergio’s observations function as ongoing commentary on the symptoms of “underdevelopment” that define contemporary Cuban society. For instance, over shots of downtown shops and boutiques, Sergio notes that Havana is often called the “Paris of the Caribbean.”

Such a descriptor seems a double-edged sword. The comparison to Paris is a way of praising the vibrancy of Havana’s cultural life, its bookstores, museums, cinemas, and modern department stores. Yet the qualification “…of the Caribbean” highlights its isolation from true taste-makers and fashionistas in New York, London, and Paris. For anyone who doesn’t live there, Havana is, at best, a playground for rich tourists from Europe and America.

As a member of the Cuban intelligentsia, Sergio often seems an unusually perceptive social critic. Yet Alea’s creation of such a strong alignment with Sergio seems designed to test the viewer’s moral and political allegiance. As a repository of pre-revolutionary attitudes, Alea’s characterization of Sergio encourages us to ask why Havana should aspire to be Paris in the first place. In a society that seeks to eliminate class distinction, why would one strive for such elitism no matter how rich and storied its culture may be?

In employing a device that often fosters sympathetic engagement with characters, is Alea just as “trapped inside the fortress” as French New Wave directors are? Actually, Alea also seems determined to turn the purpose of character alignment on its head.

As an intellectual, Sergio possesses a great understanding of Cuba’s relation to the rest of the world, but he seems determined to ask the wrong questions about its future. Therein lies the character’s great tragedy. As novelist Edmundo Desnoes observes, “His irony, his intelligence, is a defense mechanism which prevents him from being involved in the reality.” There is no place outside the palace gates for those like Sergio. Yet in probing his place “inside the fortress” Alea also shows how it rots from within.

By turning the camera’s gaze inward, Alea navigates a path between the agit-prop documentary of Solanas and Getino and the formal adventurousness of an art cinema director like Chile’s Raúl Ruiz. He set out to examine the vestiges of bourgeois thinking in Castro’s Cuba, using Sergio as a “litmus test” for Cuban audience’s political sensibilities. If you find yourself sympathizing with Sergio, seeing him as a victim of the revolution…. Well, then you better check yourself before you wreck yourself. In posing such a challenge, Alea pulls off a pretty neat trick. He manages to create a “third way” in third cinema by merging the polemical aims of agit-prop with devices and formal structures of the art film.

The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cad

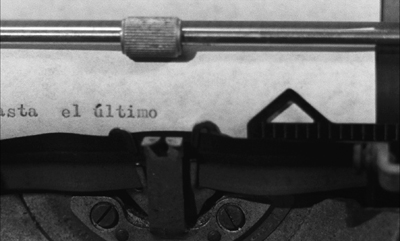

In a gesture that displays both self-consciousness and hubris, Edmundo Desnoes, the author of the novel that served as the source of the film, cast his hero as a writer. Although Alea changed much of Desnoes’ original story, this one small detail was something he preserved in his adaptation of the book. Indeed, just after Sergio has said goodbye to his wife and parents at the airport, we see him sitting at a typewriter. The sentence he writes – “All those who have loved and fucked me over up to the last moment have already gone.” – indicates both his anger in the moment and that his writing has more than a trace of autobiography.

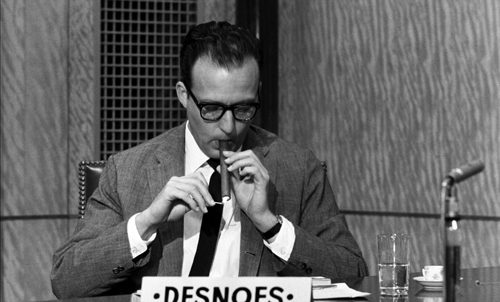

Sergio’s status as a writer encourages the viewer to see him as a surrogate for both Desnoes and Alea. This possibility is even reinforced in a scene where Sergio attends a roundtable discussion of “Literature and Underdevelopment” where Desnoes is featured as one of the panelists.

If Sergio truly is a surrogate for the filmmakers, then Alea shows some real guts in centering his film on an alter ego that is both politically reactionary and sexually predatory.

It is a mark of the film’s complexity that Sergio has certain very attractive traits even though he emerges as a thoroughly unlikeable cad. He is smart, cultured, and good-looking, for example. But he is also passive, cynical, and snobbish.

The dimension of Memories of Underdevelopment, however, that most clearly reveals Sergio’s corruption and moral rot involves his various relationships with women. Alea develops this idea throughout the film in terms of a Pygmalion motif: Sergio seeks to remake his romantic partners in the image of his first love, a German girl named Hanna.

In flashbacks, we learn that Sergio taught his first wife how to talk and dress, how to approximate a downmarket version of European elegance. Similarly, when Sergio initiates a romance with Elena, we see him taking her to bookstores and museums, trying to instill in her some appreciation for art and literature.

Sergios’ European ideals even pervade his sexual fantasies. After looking at an image of Botticelli’s Venus, Sergio imagines his housekeeper, Noemi, lying naked on his bed in a similar pose.

Similarly, when Noemi describes her Christian baptism to Sergio, he imagines it in images that seem culled from a hack romance novel. They embrace in a swoon, with their eyes locked, all wet clinging fabric and raging hormones.

Shot in slow motion, the episode is also accompanied by Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, a concert piece so familiar to most audiences that its inclusion borders on cliché.

It would be one thing, however, if Sergio’s sexual peccadilloes remained in the realm of harmless fantasy. More often than not, Alea depicts Sergio’s relations with women as episodes of exploitation and mental cruelty. A flashback to Sergio’s adolescence implies that the psychological roots of this misogyny lies in his first sexual experience as he and a school chum visit a brothel.

The transactional nature of the encounter is replicated in Sergio’s relationships later in life. After Sergio splits with Hanna, he marries Laura and is given a cushy job in the family business. He also lures Elena up to his penthouse with the promise of his ex-wife’s old clothes. In each instance, Sergio’s sexual or romantic relations with women are based on some notion of recompense: cold hard cash with the prostitute, the reward of a job with his wife, and haute couture with Elena, his new conquest.

As before, the exploitative undertones of Sergio’s relationships with women are reinforced by the film’s style. Sergio’s initial meeting with Elena is handled in a series of long tracking shots representing his optical point of view.

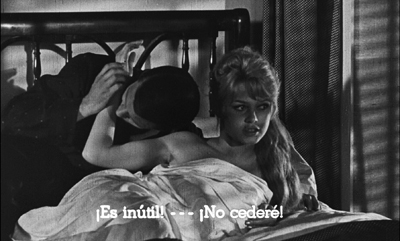

With his creepy pickup line, Sergio seems more of a stalker than a paramour. The troubling implications of this first encounter become more explicit midway through the film when Sergio literally chases Elena around his bedroom. The narrative rhyme with the earlier scene is made evident in Alea’s mobile long take, which once again represents Sergio’s visual perspective. Elena flirts coquettishly, sticking out her tongue at the camera.

But her discomfort in the situation becomes evident in her attempts to rebuff Sergio’s advances. Like the film’s use of voice-over, the moving pov shots spatially align the viewer with Alea’s unlikeable protagonist even as it implicates the audience in his victimization of Elena.

Later, when Sergio is put on trial for sexually assaulting Elena, he becomes the object of the camera’s unrelenting look along with the other petitioners. Here Alea uses a variant of the previous style. The longish takes remain. But where the previous shots used movement to suggest Sergio’s brazen advances toward Elena, the camera’s stasis within the courtroom reflects the perspective of the tribunal hearing the case. Alea cuts quite freely around the space. Still, he always returns to static close-ups of Sergio, Elena, her mother, her father, and her brother as they respond to the questions of offscreen interlocutors.

The scene proves to be the biggest challenge to the viewer’s allegiance with Sergio. He affects the demeanor of someone wrongfully accused. Yet, although the act itself is elided, Elena’s protestations beforehand and her tears afterward suggest that Sergio is probably guilty of the crimes for which he is accused. His voice-over, however, reveals his resentment toward the entire proceedings. The matter of his guilt or innocence is immaterial. What truly angers Sergio is the fact that someone of his lofty station endures treatment more suited to a common crook. He claims that he would never have faced charges during the Batista era. Sergio blames his ordeal on Cuba’s new political landscape. The judgment of his actions is more a matter of proletarian revenge rather than anything he has done.

It is easy to imagine some viewers feeling a pang of sympathy for Sergio. Jurisprudence often includes the presumption of innocence and Alea’s handling of the incident with Elena is ambiguous enough to have certain doubts. Moreover, Sergio has been impoverished by the government’s seizure of his property, something that makes his anger at Elena and her family seem more reasonable.

But what is especially striking in Sergio’s voice-over is the sense of entitlement he displays based on his previous social position. Alea seems to count on the fact that Cuban audiences in 1968 will recognize Sergio’s condescension as a symptom of pre-revolutionary ideology. His previous wealth, his education and culture, his status as an artist all sanction his satisfaction of his desires, even if that means taking the virginity of an 18-year old girl. In his characterization of Sergio, Alea not only reflects the broader influence of the French New Wave. He also revives a classic character type of French literature and cinema: the Parisian roué.

Mr. Schwitters Meets Mr. Alea: Mixing Modalities in Memories

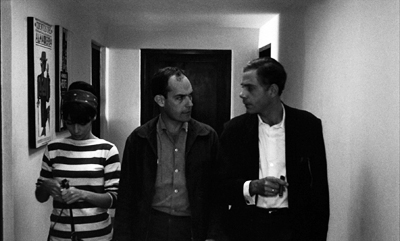

The most oft-quoted line in Memories of Underdevelopment is not something said by Sergio, Elena, or even Sergio’s brusque friend, Pablo. Instead it is uttered by Alea in a director cameo. He appears in a scene where Elena performs in a screen test at ICAIC, Cuba’s central institute of film production. Alea (center, below) shows Sergio and Elena some of his work in progress, saying, “It’s a collage. A bit of this and a bit of that.”

Most critics have noted both the self-consciousness of the moment and its layers of meaning. The footage that Alea screens is made up of scenes cut out by Cuban censors under the Batista regime. It offers a fairly dismal portrait of Cuban film history as something mostly comprised of titles imported from other colonial empires, like the Brigitte Bardot vehicle Une parisienne. This is precisely the kind of cinematic legacy that Alea and other Third Cinema directors set out to counter.

Alea’s description of his film as a collage also has been interpreted as a clue as to how one should view Memories of Underdevelopment itself. More specifically, his comment captures some sense of the film’s complex visual texture, its mix of still photographs, television clips, newspaper headlines, and even comic strip panels.

It also describes the way Alea embeds documentary footage within his portrait of Sergio as a disaffected intellectual. To some extent, this strategy is simply a continuation of Alea’s digressive approach to narration. These interpolated documentary passages fit a larger scheme that also shows fragments of Sergio’s consciousness in fleeting fantasy images and elliptical flashback sequences. Yet these segments of Memories of Underdevelopment also sharpen its political edge. In effect, Alea injects the agit-prop spirit of The Hours of the Furnaces into his “second cinema” character study.

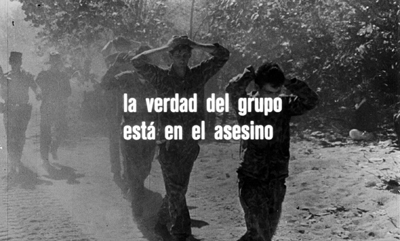

Consider the segment entitled “The Truth of the Group is in the Murderer.”

It is motivated as Sergio’s description to Pablo of the book he is currently reading. But it uses photographs and newsreel footage to explore the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the system of political repression and torture that existed under Batista. The title hints at the larger ideological point of the sequence, namely that the regime’s institutional framework served as a means of displacing and shifting criminal culpability away from its individual members. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Sergio is implicated in this dialectical arrangement between the individual and the group insofar as each part of it gives meaning to the whole.

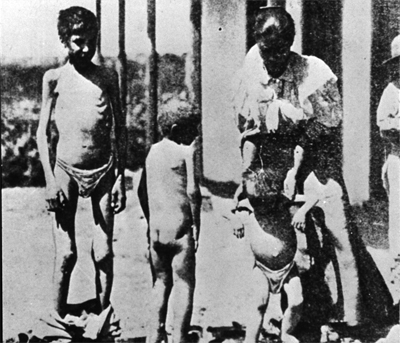

In a scene where Pablo gets his car ready for inventory, Sergio’s mind begins to wander. Alea then cuts to a series of still photos depicting hunger and starvation in Latin America.

In his voiceover, Sergio notes that the death toll from malnutrition exceeds the combat deaths of World War II. The sequence suggests Sergio’s insight into the problems of underdevelopment under capitalism. Alea’s imagery poignantly illustrates the disproportionate impact of such deprivations on society’s most vulnerable members, its children. This mini-documentary in Memories pointedly rebukes the colonialist regimes still present in Latin America by highlighting the cruel effects of such economic exploitation by First World powers.

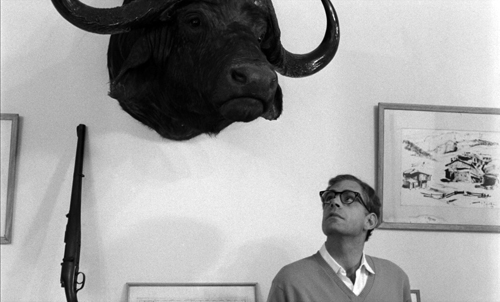

Similar sequences pop up in the episode labelled, “A Tropical Adventure.” The title refers to Sergio and Elena’s visit to Ernest Hemingway’s former home in Havana, which had been turned into a museum.

A series of photos shows Hemingway’s involvement in Spanish politics, particularly the civil war of the 1930s. A second series of photos depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his longtime servant Rene Villarreal. In his voiceover, Sergio hints that their master-servant relationship captured some of the vagaries of American imperialism. Sergio concludes that Hemingway must have been unbearable.

Sergio’s voice-over during these sequences offers one of the clearest statements of his character’s dualism. He conveys sympathy with Villarreal as a fellow Cuban and recognizes that Hemingway’s paternalism is itself an expression of colonialist ideology. Yet Sergio also seems to identify with Hemingway’s social position given his elite status as a rentier and aspiring writer. His trenchant observations about Hemingway’s relationship with his servant is an unwitting acknowledgement of how easily he could slip into the shoes of the great American author and adventurer.

In the battle for Sergio’s soul the “great white hunter” wins out as we see him hiding from Elena until she just gives up and walks away. Sergio’s condescending treatment of Elena is merely the flip side of the imperialist dialectic expressed by “the faithful servant and the great Lord. The colonialist and Gunga Din.”

Memories’ political sophistication largely derives from Alea’s sensitive treatment of his protagonist’s inner conflict. As a remnant of a previous historical moment, Sergio’s jaundiced perspective suggests that life under the Castro regime has simply substituted a new set of problems for life under the Batista regime. Indeed, for many viewers circa 1968, Alea’s look back at the era between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis might seem an endorsement of his hero’s nihilism and fatalism. Such was the case for several U.S. film critics who Alea disparaged later, claiming that their identification with Sergio caused them to mistakenly privilege the depiction of the artist’s self-interest over the needs of Revolution.

As Alea wrote more than a decade after Memories of Underdevelopment was released, “In Cuba, the Revolution is in power. This means that the conditions of struggle have changed.” Sergio’s struggle to find his place within post-Revolutionary Cuba becomes a metaphor for struggle itself. It is easy to celebrate the moment of triumph when a nation overthrows its oppressors. But a society’s problems don’t just disappear when you have regime change. Memories is the rare film that confronts the challenges faced in the aftermath of any revolution. It takes a hard look at the difficulties in remaking both a society and culture caught in the shadows of two global superpowers: the US and the USSR. In Alea himself put it:

It is to the spectator that the film should reveal the symptoms of possible contradictions and incongruities between good revolutionary intentions – in the abstract – and a spontaneous and unconscious adherence to certain – concrete – values belonging to bourgeois ideology.

Sergio simply becomes the vehicle through which Cuban audiences were encouraged to consciously grasp their own contradictions.

Alea’s insights here attest to his remarkable achievement in Memories of Underdevelopment. By exploring Cuba’s travails after Castro’s seizure of power, Alea knew that First World audiences might misinterpret the film. They might even use Memories to affirm their own imperialist identity. Yet this was not a design flaw. Instead, the film’s vulnerability would also turn out to be its greatest strength among domestic Cuban audiences. Alea’s use of cinematic devices to convey subjectivity imparts a simple but powerful lesson: the Revolution may be over, but revolutionary struggle never ends.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work. Also thanks to our colleague Erik Gunneson.

The text of “Toward a Third Cinema” is widely available on the Internet, as here.

The most useful resource for information on Memories of Underdevelopment remains the volume in Rutgers Films in Print series. The book contains a reproduction of the continuity script, a reprint of Edmund Desnoes’ original novella, contemporaneous reviews, and Alea’s own reflections on the film some twelve years after it was released.

The film was rereleased in 2018 after undergoing a 4k restoration. Reviews can be found here, here, here, and here. An interview with director Tomas Gutiérrez Alea can be found here. An excellent overview of Alea’s career in its entirety can be found here.

Here’s a complete listing of our Observations series on the Criterion Channel. Our installment on Hiroshima mon amour provides an intriguing comparison to this entry.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).