Archive for October 2019

Beach blanket ballads: SUN & SEA (MARINA)

Sun & Sea (Marina) (Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, 2019).

DB here:

Excitement, shock, tension, maudlin sentiment–these and other emotional qualities are pretty common in artworks. But how often do we get what I’m forced to call anxious languor? That seems to me the dominant expressive quality of the remarkable Lithuanian opera Sun & Sea (Marina), which won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the Venice Biennale.

It’s not a film, but having read about it before going to the Mostra, I was keen to see it. Kristin and I were not disappointed. It’s the work of director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė, and composer Lina Lapelytė. You can watch extracts here and here and here.

Video clips, or indeed a full-length record, can’t capture this unique spectacle. And of course it set me thinking about film.

Duet in the sun

Sun & Sea: Marina portrays a group of people at the beach. Instead of being mounted on a stage, the action, such as it is, takes place on a ground floor of a warehouse. You view the ensemble from catwalks above. On the sand below are pastel beach blankets, personal belongings, and some litter. Thirteen singers and some civilians lie reading or snoozing or listening to cellphones. A woman deals out Tarot cards. There’s a little boy playing in the sand, dudes tossing a frisbee or playing badminton, and occasionally a couple’s dog needs walking. The dog barks from time to time.

The piece lasts about seventy minutes, recycled so you can enter at any point. At the Biennale, it was initially open only one day a week, but later you could attend on either Wednesday or Saturday. The queue wasn’t impossible; I think we waited about half an hour.

The looped nature of the presentation works against there being a plot, and there’s scarcely any characterization. The libretto identifies the Wealthy Mommy, the Volcano Couple, the Workaholic, the 3D Sisters (twins), and others, but when you’re watching it, you’re much more aware that this is about particular bodies in a specific space.

The music, in the lyrical minimalist vein, consists mostly of arias, characters’ soliloquies backed up choral passages. There’s an organ ostinato recalling Philip Glass and tunes that reminded me of the lilting faux-naīveté of Meredith Monk. The rhythm is alternately solemn and bouncy, the phrases are brief, and the mood of the whole score seems summed up in the soaring Chanson of Too Much Sun:

My eyelids are heavy,/ My head is dizzy,/ Light and empty body./ There’s no water left in the bottle.

Some of the arias, like this one, report thoughts caught in the moment. The first and last songs are Sunscreen Bossa Novas, sung by a middle-aged woman worrying about protecting her skin. Another woman complains about dogshit and spilled beer in the sand. One of the most moving passages is the Chanson of Admiration, a breathy soprano solo:

What a sky, just look, so clear!/ Not a single cloud,/ What is there?–seagulls or terns?/ I can never tell./ O la vida/ La vida…

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Sun & Sea (Marina) has been considered a commentary about our poisoning the planet, and the booklet included with the LP of the score includes essays about climate change. But the opera as staged invokes the crisis obliquely and poetically. One passage notes that the seasons are out of joint at Grandma’s farmhouse, with frost and snow in May and Easter weather during Christmas. It’s presented not as a warning but as a puzzling development. A recurring line in the songs is “Not a single climatologist predicted/ A scenario like this,” and it’s applied to love affairs as well as volcanic eruptions. The crises of the Anthropocene era are refracted through personal relationships.

Environmental degradation is registered through the sensibility of drowsy vacationers. The twin sisters are distressed to learn that coral and fish will perish, but they console themselves that a 3D printer will produce enduring copies of everything, including the girls themselves. (“3D Me lives forever.”) Even pollution right under your nose is filtered through the dazzling torpor of a day at the beach. One of the loveliest songs invites us to imagine that the sea is acquiring new beauty.

Rose-colored dresses flutter;/ Jellyfish dance along in pairs–/ With emerald-colored bags,/ Bottles and red bottle-caps./ O the sea never had so much color!

In all, though you might register some perturbations in the ecosystem, you come away from lolling on the sand feeling pretty good.

After vacation,/ Your hair shines,/ Your eyes glitter,/ Everything is fine.

Eisenstein on the beach

What about cinema? Seeing something so resolutely presentational makes you think about what film can’t do. The online videos only hint at the decentered, dispersed quality of the opera. Some of the action takes place directly under the catwalks, so you can’t take in the ensemble at a single glance. We had to move around to get a sense of what had been happening underneath us.

Just as important, nobody in the audience is significantly closer to the stage than anybody else. Cinema of course has what Noël Carroll has called variable framing, the ability to change the scale of the material in the image (through cutting, camera movement, zooming, optical effects, digital postproduction). Even in proscenium theatre, the people in the orchestra see more details than those in the balcony. But Sun & Sea (Marina) keeps everybody pretty much at the same distance from the spectacle. We can fixate on some figures rather than others, and we can enlarge them artificially via the zoom on our cellphones, but the naked eye has to take in the whole thing at once, all the time. And even that’s not really the whole thing.

The sense of dispersed action is strengthened by the surround-sound speakers. They delocalize each voice. You have to search the array of bodies to find the soloist, and when a song is tossed from singer to singer it scrambles your attention. This might remind a cinéphile of Jacques Tati’s compositional strategies, particularly in Play Time, where long shots coax us to scan the image to find a sound’s source. But at least Tati had a more restrictive frame. Sun & Sea (Marina) plants us in a three-dimensional field with only partial access to the entire scene.

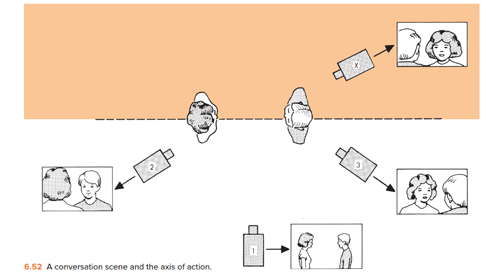

That access is, of course, a very unusual one. When I was first studying classic continuity editing, with the 180-degree rule and matches on action and all the rest, I wondered: Would that system work if the camera were pointing straight down at the actors? That is, what if we constructed a whole story from variants of the bird’s-eye view we use to diagram spatial layouts? Instead of this:

We’d have movies with shots like this.

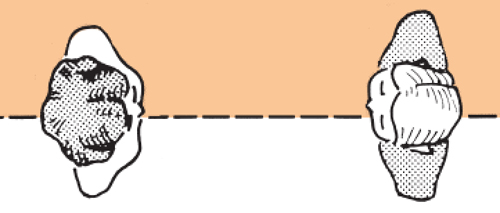

We’d apparently lose the eyeline match, at least! We’d also have to distinguish characters in unusual ways, by hats and hairstyles and maybe boutonnieres. But I was assuming a drama in which people moved around on foot and had face-to-face encounters. Sun & Sea (Marina) suggests that another way to build a vertically viewed spectacle is to show people sprawled out on belly, back, or side–postures motivated by the beach setting.

Then perhaps we could, through editing, create “reverse angles” from straight down. Or couldn’t we?

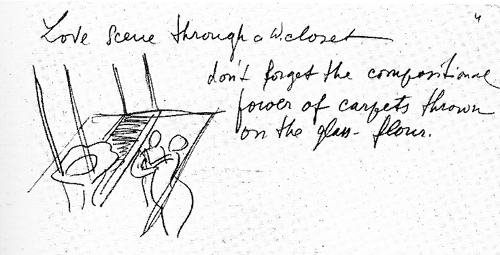

Actually, as usual, Eisenstein was there ahead of us, in his plans for The Glass House, a film set in a skyscraper made of glass. The transparent walls would let us see what’s happening next door, while the floors would create a stacked space, presenting actions from more or less straight down. Naughty as he was, he even conceived a “Love scene through a water closet.”

In one note, he called the film’s view “A Hovering Space”–not a bad description of what we see in Sun & Sea (Marina).

I’m still thinking about this remarkable piece of work, about the anxious languor it projects and its ways of building a scattered scene out of microactions. But I’m also enjoying remembering the sheer sensuous pleasure of it. I hope that somehow I get to see it again. I hope you can too.

Our visit to the Biennale was made possible by the generous invitation of Peter Cowie, Savina Neirotti, Paolo Baratta, and Alberto Barbera. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich. Michael Philips of the Chicago Tribune and Keith Simanton, Senior Film Editor and Content Manager of IMDB, accompanied us to the show and proved fine company.

There’s a very informative interview with the artists (who have been friends since childhood) here at BarbART. It includes footage from their earlier collaboration, Have a Good Day! Background on the artists can be found at Neon Realism. The score is available as an LP. It includes a custom code for downloading an mp3 file. Beware: Many earworms wriggle within.

Of course Sun & Sea (Marina) reminds you of another Tati masterpiece, M. Hulot’s Holiday. Kristin long ago wrote a careful analysis of that film with a title I might have borrowed for this: “Boredom at the Beach.” It’s in her collection Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. Also on Tati: Watch for Malcolm Turvey’s excellent forthcoming study Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism.

The diagram of the 180-degree editing system comes from Film Art: An Introduction. Photos in this entry by DB.

P.S. 15 September 2021: Sun & Sea (Marina) is coming to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019).

Vancouver 2019: Some final observations

It Must Be Heaven (2019).

We wrap up our coverage of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival with a joint entry on movies from around the world.

Kristin here:

Out of Tune (2019)

Danish director Frederikke Aspöck has created a prison film with a seamless combination of humor, social commentary, and a subtly disturbing undertone.

Markus Føns arrives in jail, awaiting trial for corporate fraud. As a result of his popular financial advice books, he is notorious for having caused many to face financial ruin. He runs into the thuggish brother of a man who has lost a huge amount through Markus’ advice. The brother insists that Markus is owes the brother the full amount he lost. He dismisses Markus’ point that all investments are a gamble and, along with his gang, beat Markus up.

Terrified of further violence, Markus voluntarily transfers to the solitary-confinement wing, joining rapists, child molesters, and others who fear being attacked by other inmates. The prisoners in this wing are not really isolated, however. They’re let out to do chores, to sing in a choir, and to earn a bit of money by making pom-poms for local schools and celebrations.

The choir members (above), led by Niels, prove an engaging bunch, and much humor is generated by their disagreements about which songs from a collection of Danish classics they should sing. Markus initially sticks to his cell but finally joins the group. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, Niels insists that Markus is not a tenor but a bass, forcing him to sing in a range that clearly is not natural to him.

One of the rules of solitary is that the prisoners are not allowed to reveal or discuss their crimes–though Markus is famous enough that all the others know what he did. Simon, a genial young black man, admires Markus and increasingly becomes his ally against the dictatorial Niels.

Gradually the tone darkens, however, as it is revealed that two of the main characters, including Niels, are pedophiles. Markus declares that his white-collar crimes are less heinous than child molestation. The others, however, including Simon, declare Markus’ crimes worse. At that point he decides to take his revenge on the group and especially Niels, by seizing the leadership of the choir.

This balancing act between humor and drama works well, with Aspöck managing to make the pedophiles somewhat sympathetic and amusing characters without excusing their crimes. The satire on how upper-class celebrity criminals like Markus manage to become objects of fascination is effective without becoming heavy-handed.

It Must Be Heaven (2019)

I am a fan of the Palestinian director Elia Suleiman, who manages to make autobiographical feature films at wide intervals. I am particularly fond of Divine Intervention (2002) and I also like The Time That Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee, which we saw in Vancouver in 2009.

It Must Be Heaven does not quite achieve the excellence of those earlier two films, being a bit uneven. Still, it contains many excellent scenes and gags, and it was among the best films I saw at this year’s festival.

The earlier portion sets up Suleiman’s sense of unease about the events that surround him in his native Nazareth. A running motif has him peeping timidly over his back wall as his neighbor’s son without permission picks lemons from his trees. Gradually the man takes over the care of the whole orchard.

Eventually Suleiman goes abroad, and we soon learn that he is seeking funding for his next film, presumably the film we are now watching.

Two of the funniest scenes take place in the offices of the producers Suleiman visits in Paris and New York. Both end in failure, but the huge number of international companies and funding agencies listed in the credits suggests that the director’s efforts must have been complex, lengthy, and, in some cases successful. The scene in New York involves a cameo by Gael García Bernal, who has an offer on a Mexican project of his own, but he obviously has little control of that project, let alone the ability to aid his friend Suleilman. The one in Paris has Vincent Maraval, of Wild Bunch (one backer of the film) playing a producer who rejects the project as not Palestinian enough.

Other than visiting producers, Suleiman wanders the streets of Paris and New York, observing incongruous events around him. Some of these are very amusing, others simply odd.

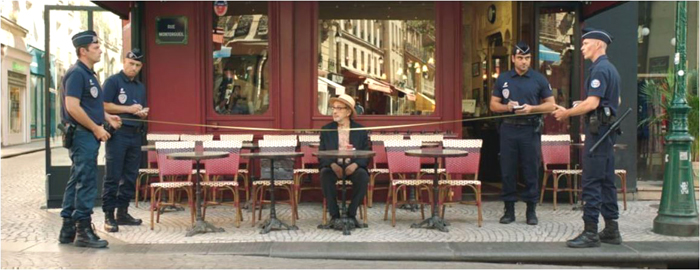

Comparing It Must Be Heaven to Suleiman’s earlier “autobiographical” films, the basic problem here becomes apparent. While Suleiman (or an actor playing him as a child) wove in and out of the action, participating in it, here many scenes involve him as a largely passive observer of events that have little or nothing to do with him. In one such scene, he sits at a cafe table, watching as four police officers carefully measure the spaces of the outdoor tables before pronouncing them compliant with regulations (see top). In Palestine he walks in the country and observes a Bedouin woman with a novel way of transporting two large vats of liquid. In Paris he observes police on Segways performing a search in the street below in perfectly choreographed loops. At times he is more affected by the action, as when a tattooed muscle-man stares at him threateningly in an otherwise empty Métro car.

Suleiman is an engaging performer, but watching him stare in bemusement at the odd behavior that he encounters in each place he visits grows a bit old. Nevertheless, there are many funny or just bizarre scenes in the film, including a lengthy tussle between Suleiman and an invading sparrow determined to perch on his keyboard. The visit to Paris, in which Suleiman somehow got the streets emptied so that he wanders completely alone through them is both impressive and somewhat disconcerting (above).

Suleiman is routinely compared to Tati and Keaton, but his work is similar to that of Roy Andersson too, is equally apt, although Andersson does not assign a single character to be an observer. Here to a considerable extent Suleiman keeps to the long-shot framings that are familiar from his other films, but there are also more close-ups, in particular of his face as his reacts to what he sees.

It Must Be Heaven suggests that wherever Suleiman goes once he leaves his Palestinian home, he sees the same sorts of odd behavior, especially the violence that has become endemic everywhere. (A particularly hilarious episode shows Suleiman shopping in New York and noticing that everyone around him, including babies, is carrying some sort of weapon, from pistol to bazooka.) I suspect, however, that most viewers would fail to catch the political points Suleiman claims in interviews to be making.

DB here:

Oh Mercy (Roubaix, une lumière)(2019)

Arnaud Desplechin regards his previous films (Esther Kahn, Kings and Queen, A Christmas Tale) as “a fireworks of fiction,” as he explained in a Q & A session. His latest, Oh Mercy, is based on fact. The screenplay dramatizes criminal cases that took place in Roubaix, the impoverished town Desplechin grew up in. The result is an unusual policier, which twists some crime-movie conventions in intriguing ways.

As we expect, the cops form a team. The emphasis is divided between the young and eager Louis Coterelle and the experienced chief Daoud. But Coterelle is an ascetic young man, reminiscent of Bresson’s country priest. Daoud, rather than being the tough boss who has to make his staff shape up, is an eerily quiet and sympathetic professional. Cast out by his family, he devotes his life to his work (and the occasional horse race). These characters keep surprising us. It’s the pious Coterelle who, pushing to make his mark, bullies suspects, while Daoud’s gentle ways eventually tease the truth out of them.

The police procedural typically shows several cases worked at once, with some minor ones and others explored in more detail. Desplechin’s film does the same, as an automobile fire and a petty robbery introduce us to the main cops. To help a friend, Daoud must also investigate a runaway teenager. Soon there’s a building fire, and then a murder on the same block. Gradually it becomes clear that these two crimes are connected–another convention of the genre.

It’s the nature of the connection, though, that reveals Desplechin’s originality. About halfway through the film the police commit their energies to questioning two women, Claude and Marie, who share an apartment. In a string of riveting interrogations, the film shows Coterelle and Daoud, each in their own way, peeling back layers of the women’s relationship. It’s a tour de force relying on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and it reveals as much about the cops as it does about the sad, confused lovers. Even the reenactment of the crime, another staple of the genre, avoids sensationalism and achieves a mournful gravity.

Most cop movies make justice a matter of vengeance (“This time it’s personal”), so it’s rare to find one about pity. The lies and mistaken memories that prolong the investigation are accepted by Daoud with quiet compassion. A gradual-revelation film like this, impeccably plotted and directed though it is, depends crucially on performances, and the principals (Roschdy Zem as the patient Daoud, Léa Seydoux as Claude, Antoine Reinartz as Coterelle) are extraordinary. Above all I will remember Sara Forestier as the skittish Marie, perpetually corrugating her forehead, always a beat behind in appraising how much the woman she loves loves her.

Once more we thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies. In addition, we appreciate the generosity of Arnaud Desplechin in answering questions about his film.

Oh Mercy (2019).

Vancouver 2019: Tales of oppression and resistance

Bacurau (2019).

Kristin here:

Examinations of social problems and portrayals of downtrodden people are fertile ground for makers of art cinema. This year’s festival saw many films from around the world tackling such subjects in original ways. Here are four impressive instances.

Castle of Dreams (2019)

Reza Mirkarimi is one of Iran’s top filmmakers, with three of his films having been put forward as Iran’s nominee for an Academy Award. In Castle of Dreams he has created a sort of nightmare version of the traditional child-quest tale so popular when Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf were at the heights of their careers. The protagonist, Jalal, has recently been in jail. The film opens as he is making some sort of a deal by telephone. His wife has just died after a protracted illness, and his sister-in-law, who had been taking care of Jalal’s two young children, is forced by her husband to turn them over to Jalal. But he clearly wants nothing to do with them.

Jalal sets out with them in his late wife’s car, picking up his Azeri fiancée on the way to Azerbaijan. He continuously snaps at the small children, Sara and Ali, and at his fiancée. It eventually comes out that he had taken his wife off life support and sold her heart for transplant, all without telling her brothers. Despite his occasional clumsy attempts to be kind to the children, any expectations that the audience may have that he will be charmed by them and transform into a responsible father are far too optimistic.

If this were a traditional child-quest plot, Sara and Ali might struggle to get back to their kindly aunt. Here, despite becoming increasingly miserable as Jalal’s full villainy is revealed, they are essentially prisoners in the back seat of the car (above). Ultimately the film takes a clear-eyed, realistic view of the future for this little family.

The acting carries much of the film. Hamed Behdad won a best-actor award at the Shanghai International Film Festival (where the film also won the best-picture prize). The child actors are charming and elicit considerable sympathy for their plight.

Song without a Name (2019)

Inspired by a real-life case that her journalist father investigated, Melina León’s first feature successfully generates sympathy for her two main characters and recalls the horrors of the past. Set in 1988, it follows Georgia, a pregnant indigenous woman living in a shack near the sea and scraping by as a street-seller of potatoes (above). Lured in by a radio ad, she visits a free clinic with a reassuring name, the “Saint Benedict.” The organization is anything but benevolent, however, spiriting her newborn daughter away for “check-ups.” Desperate to find the baby, she and her partner Leo encounter only indifferent police and other other government officials.

Eventually she finds a sympathetic helper in Pedro, a reporter who confidently promises that they will recover her baby, despite the fact that it has most likely been spirited out of the country for adoption. While Pedro pursues his investigation, Georgina finds her ability to purchase wholesale potatoes shrink in the face of rampant inflation, on top of which she discovers that Leo is apparently a member of the Shining Path terrorist group. Pedro meanwhile starts an affair with a gay actor in his apartment block, only to be threatened with exposure and death, presumably by the gang that runs the baby-stealing operation.

The film will inevitably be compared to Roma, even thought the films have nothing substantive in common. Both are black-and-white, Latin American films, and both heroines are pregnant; that’s the extent of the resemblance. León’s film has nothing of the nostalgia that permeates Roma, and Georgina is far more marginalized and downtrodden than Cuarón’s heroine.

León also is working with a far smaller budget and yet with the help of cinematographer Inti Briones she has fashioned a sophisticated and lovely film. One lengthy shot is particularly impressive. In it Pedro meets with a potential witness in a small motor boat. The camera, in another boat, catches it as a pulls away from the dock and glides around it as it turns,

The camera moves rightward with the boat but also moves in to show the woman sitting, apparently alone, in the boat.

A move further away establishes that Pedro is present, and we watch as the woman walks forward to sit beside him.

As she warns him of the danger of pursuing the kidnapping gang, the camera moves slowly in to emphasize her revelation that years before she had sold her baby to them

All the while the huge shantytown glides past in the background, emphasizes the extent of the poverty in the outskirts of Lima. The choreography of camera and action in this two-minutes-plus shot could hardly be bettered in a production with many times the budget. (A clip of this long take is currently posted on Youtube.)

The title seems to refer to the lullaby that Georgina sings, just calling her lost child “baby” because she never was given a name.

The film played in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where it received positive reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. It deserves further festival play, and we can hope that León can follow up with other films.

Sorry We Missed You (2019)

Then there is, Ken Loach, the veteran English filmmaker who continues to deal movingly with the plight of working-class people. In Sorry We Missed You–which deceptively sounds like a title for a comedy–tackles the gig economy and its grinding effect on one industrious couple and their children.

The inevitability of bad consequences seems obvious as the husband of the family, Ricky, agrees to become a driver for an express delivery service which transports packages for the likes of Amazon and other online sellers. He is not an employee but an independent agent, the supervisor emphasizes. Buying his own van supposedly will cost less than leasing, so he sells the family car for a down payment. His wife Debbie, a caregiver for home-bound elderly and handicapped people, is forced to take the bus to her widely scattered clients.

The couple’s long hours begin to tell on their teen-age son, who is turning into a school-skipping, graffiti-spraying delinquent, and their younger daughter, who is crushed by the stress of watching her family falling apart.

Loach is expert in depicting the challenges of such a job, from the pressure for drivers to load packages onto the van rapidly (bottom) to Ricky’s indecision over whether to risk a fine for illegal parking or deliver a package late (above). As he misses deadlines and skips work over family crises, the company’s sanctions and fines begin to accumulate. Ricky spirals into debt. Debbie, torn between duty to her family and the people who depend on her, faces similar problems in dealing with her helpless clients.

There is no happy ending here, though there is some suggestion that the dire situation of the family at least forces them to try and help each other out. Loach has created a plausible, gradual descent into near despair. He portrays the pressures of large companies and organizations that expect much of their “independent contractors” but offer little support in return.

Bacurau (2019)

At first glance, Bacurau represents a considerable departure from Kleber Mendoça Filho’s two previous films, both of which we saw at VIFF, Neighboring Sounds and Aquarius. Both dealt with unscrupulous methods used by real estate dealers to push people out of older neighborhoods to make way for gentrification. Now, co-directing with Juliano Dornelles (the production designer on the two previous films), Filho departs from the big city for a small village in the wilds of northern Brazil. The village, by the way, is imaginary, a fact that provides a running joke about the characters’ inability to find it on maps.

Someone in power wants the villagers to leave, again to make way for the exploitation of the land for undisclosed purposes. In a way, it’s not such a departure from the previous films as it seems. Blocked water sources and inadequate food deliveries have failed to budge the villagers, who make do on their own. The film opens with two villagers in a tanker truck full of water bound for Bacurau (above).

Having failed to uproot these determined peasants, the unseen power has brought in a group of wealthy hunters who are keen to gun down human beings and have been given carte blanche to exterminate the entire village. Delivery trucks appear with cargoes not of food but of dozens of empty coffins, a few of which are soon used for the first victims of the hunters (see top).

Despite the suspenseful and sometimes gory action, the film has considerable humor. It soon turns into a modern version of the politically charged Cinema Novo films of Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s. The peasants prove less helpless than they initially appear, and soon the hunted are hunting their hunters.

By this point members of the audience with whom we saw the film were cheering, and obviously there was a contingent of Brazilian speakers who got some jokes that we didn’t.

All in all, it’s a wild, entertaining film, though not for the faint of heart.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sorry We Missed You (2019).

The trim, tight movie: Three variants at Vancouver

Parasite (2019).

DB here:

As a student of storytelling, I recognize that we can enjoy loose, episodic plots. But I also admire the shrewd craft of constructing a movie that develops a situation in precise, logical, yet surprising ways. Things may be resolved neatly, or not, but the satisfaction comes from the way that characters pursuing goals create conflicts, overcome obstacles, and change (or not) in the course of the action. American studio cinema developed its own version of this in what Kristin and I have called “classical Hollywood” plotting. Other countries have borrowed that model, adapting it to new needs but still keeping the storytelling trim and tight.

Three films on display at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival illustrate some options. All have won acclaim at other festivals and constitute A-productions in their local industries. I enjoyed all of them, and I liked learning how broad principles of narrative construction can be treated in significantly different ways.

Storming the basilica

François Ozon’s By the Grace of God, a prizewinner at Berlin this year, turns Spotlight (2015) inside out. The American film follows the investigation of a news team bringing priestly pedophilia to light; it’s a detective story, with the victims serving as witnesses to the crime. By the Grace of God concentrates on the victims’ search for justice, and finds an unusual structure to give each one due weight.

The film is based on a real case in Lyon. The film starts with businessman Alexandre Guérin accusing Father Preynat of abusing him as a child. Surprisingly, Preynat admits he did the deed, so there’s no mystery to be solved. With the statute of limitations expired, the Church authorities decline to punish Preynat. He’s kept in service, and his duties still associate him with children. The only thing that worries Cardinal Barbarin is that Preynat didn’t apologize when Alexandre confronted him.

A pious Catholic, Alexandre trusts that if he appeals high enough in the Church hierarchy (even up to the Pope), some action will be taken. He is rudely awakened to the cynical willingness of Barbarin to stall and cast a smokescreen over the case. Alexandre decides to file a legal complaint and to find other victims to join him.

At this point, Ozon’s script takes an intriguing turn. The plot drops Alexandre and introduces us to another victim, François Debord, who is a fairly militant atheist. Investigating Alexandre’s charges, the police call on François’s parents. He told them of the abuse at the time, but they pressured him to stay quiet. Now he embarks on a crusade to find other victims to speak out. For some of them, the statute of limitations may not have expired.

Alexandre becomes a minor player in this stretch of the film, meeting François occasionally to plan strategy, but François is the motor of the action. His zeal leads him to yet another victim, Emmanuel Thomassin. We now follow him and learn how his life has been damaged quite severely by Preynat’s abuse.

Eventually the three men find more victims willing to go public, and by cooperating they confront the Church’s coverup.

With three sections each lasting 45-50 minutes, Ozon has mounted a block-construction plot (although without explicit chaptering). He has compared it to a relay race, with the story impulse passed like a baton from one character to another. And each phase of the action raises the stakes: growing proof of the Church’s malfeasance, a broader survey of the consequences of the crimes.

Ozon has also said that he tried to distinguish each of his three protagonists’ sections stylistically. Alexandre’s phase of action has highly economical narration, using the exchange of letters and emails (read in voice-over) to move the action swiftly, forcing us to keep up at every moment. When the action shifts to the flamboyant, web-savvy François, the emphasis falls on building online support for an organization. Emmanuel’s painful story is treated with more intimacy and empathy; the other men have overcome their childhood traumas and have buoyant families, but Emmanuel is adrift.

By the Grace of God has the carpentered solidity of Ozon’s Frantz (2016). If we can say that the French “Tradition of Quality” of the 1940s and 1950s persists today, it’s surely here in this taut, elegant piece of storytelling.

City on fire

Stylistically, Les Misérables doesn’t look as sleek and controlled as Ozon’s film. It’s shot in the free-camera style that’s now common throughout the world: handheld shots, fast cutting, tight framing on faces, lots of panning to follow the action. When cops brace three women on the street we get a rapid-fire exchange in the manner of Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Although we’re basically on one side of the confrontation, the cutting is somewhat freer than in classic continuity, as the above shot of Stéphane indicates. To emphasize the quasi-sexual gesture of Chris checking the young woman’s fingers for the smell of pot, the editing jumps the line before returning to the main setup.

Les Misérables, directed by Ladj Ly, is not quite as pure an example of the free-camera approach as Young Ahmed, (also shown at VIFF) because it affords a greater degree of “camera ubiquity.” It crosscuts among lines of action, and it relies on reaction shots that the Dardennes avoid. Still, the purpose is to immerse us, smashmouth fashion, in each scene’s conflict.

And there’s plenty of conflict. Stéphane Ruiz has joined a team of tough cops patrolling an impoverished Parisian suburb teeming with immigrants. To keep things under control Chris, the team leader, has formed alliances with drug gangs and the boss of the territory. Gwada, a Muslim cop, backs Chris loyally.

The main action, which consumes around 24 hours, shows Stéphane trying to bring a measure of humanity to the confrontations between his unit and the local residents. A petty crime escalates into a burst of police brutality, captured on video by a boy’s drone. The second half of the film puts the cops in conflict with one another and an increasingly outraged community ready to take on both the police and the gang leaders.

Ly has made short films and web videos, and while growing up in the banlieue projects he documented police actions.

For five years I filmed everything that went on in my neighborhood, particularly the cops. The minute they’d turn up, I’d grab my camera and film them, until the day I filmed a real police blunder.

Ly filmed the 2005 riots as well (365 Days in Montfermell), as part of the filmmaking collective Kourtrajmé. Les Misérables is called that partly because this is the district where Hugo wrote his masterpiece. “I wanted to show the incredible diversity of these neighborhoods. I still live there: it’s my life and I love filming there. It’s my set!” In 2018 Ly established a filmmaking school in Montfermell.

Although Ly comes from the world of documentary, he has a shrewd sense of fictional plotting. A prologue shows little Issa among thousands of Parisians celebrating France’s World Cup victory (above). It’s an image of diversity within national unity, but also a bit of narrative priming that makes us sympathetic to the boy. The rising tension of the action, from a childish prank through increasingly horrific scenes (one in a lion’s cage had me trembling) to a final cataclysm, is carefully constructed out of a series of misunderstandings, brutal decisions, overreactions, and desperate survival maneuvers.

There’s solid motivation and foreshadowing. The drone is established early as the all-seeing eye of the projects, steered by the withdrawn boy Buzz. Stéphane has reluctantly transferred to the Parisian police from the provinces because he wants to be near his son, in the custody of his ex-wife. This information prepares us for his sympathetic gestures toward the children of the projects. And just before the climax, Ly’s script gives us a pressurized nighttime pause, a sequence that cuts among all the adults we’ve seen trying to adjust to the day’s turmoil. Next day all hell will break loose.

Les Misérables shared the Jury Prize at Cannes last May with another VIFF entry, Bacunau. (Comments on this coming soon.) In the US it will be distributed, who knows how, by Amazon.

Class struggles

Viewers of Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Mother (2009; also here) know that Bong Joon-ho has a fine hand with mystery, suspense, and abrupt plot twists. His skill is on full display in Parasite, Palme d’or winner in Cannes and already considered one of the most striking films of 2019.

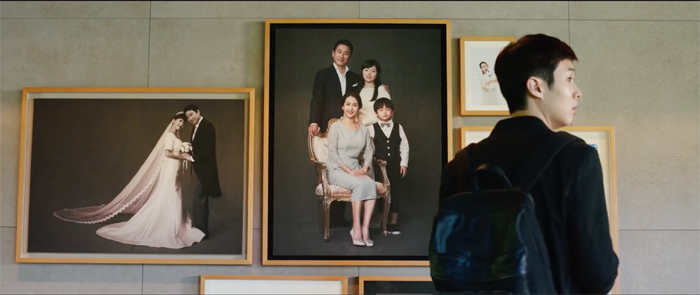

As suits the Age of Inequality, the action centers on two families. The Kims live in a crammed basement and struggle to get by. When the son Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter of the rich Park family, he schemes to insert all his family members into the household. (This recalls the stratagems of the play and film Kind Lady.) The Kims’ adroit manipulation of the Parks, especially the insecure helicopter mom, provides mordant comedy. But in a long central scene, the Kims’ scam starts to unravel. They’re shocked to discover what actually goes on in the splendid mansion they’ve taken over.

Bong’s skill in shooting, staging, and composition seems effortless. Neither as academic as Ozon or as nervous as Ly, his deliberate style makes every sequence build to a neat point. The contrast between the Park house, perched high on a hill, and the Kims’ basement apartment, is echoed in vertical camera movements that carry us up and down through locales. (Here, in more instances than one, the poor live underground.) Parasite‘s opening camera setup, a view of the street through the Kims’ window, recurs at various points to mark stages of the action. Here nighttime violence erupts in the street outside.

The Kims’ barred view contrasts with the spacious picture window at the Park mansion. Fussy as ever, Bong places a comparable shot of the Kim window at the very end.

Bong plants significant motifs through the film. He forgets nothing. Cub scouts, Morse code, peach allergies, and the smell of poverty pay off in comedy while supplying thematic resonance. The parallels between the married couples are enhanced by the introduction of another husband and wife who have launched their own desperate scheme. The climax, an orgy of rich folks’ complacency, brings all together in a shocking but not ultimately surprising confrontation.

I had almost called this entry “The well-made movie,” indicating not only my praise for the films but also their kinship with the dramatic tradition of the “well-made play” (pièce bien faite). That was one powerful set of principles for plot-building. If you construe that form narrowly (as the Wikipedia entry does), these films don’t completely fit it. I think that Ibsen, Shaw, and those who followed owe more to that form than is generally admitted.

In any case, the impulse toward tight construction, full motivation of characters’ actions (usually guided by a goal), and a rising arc of conflict leading to a decisive climax–these design features, so manifest in the well-made play, have carried over to the cinema since the rise of the feature film in the 1910s.

Today’s films have a look and feel that seem of our moment, but their underlying “engineering” principles are surprisingly indebted to a long-running tradition. Those principles can be deployed, revised, and reversed in a great many ways–as these three films show.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on the general principles of “classical” construction, see this entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema Kristin traces some literary and dramatic sources of the format.

On the “free-camera” shooting style, see our blog entry on Toni Erdmann (viewed at VIFF back in 2016). We discuss the emergence of the technique in Chapter 25 of the fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

By the Grace of God (2019).