Archive for March 2020

Flicker Alley fills the Pudovkin gap

The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley continues its editions of classic silent films previously unavailable on disc or available only in inferior copies. Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features, Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927), and The Heir of Genghis Khan (commonly known in English as Storm over Asia, 1928), are packaged here as “The Bolshevik Trilogy.” (As of now, the discounted price at Flicker Alley’s own site is considerably cheaper than what Amazon is charging.) All three films have appeared in my annual survey of the ten best films of ninety years ago; see the entries for 1926, 1927, and 1928.

The only restoration in the set is Storm over Asia, done in connection with Lobster Film in Paris.

Mother

Pudovkin’s trilogy is a sort of survey of key events in Russia’s move toward becoming the Soviet Union. Mother, based on Maxim Gorki’s novel of the same name, deals with the failed Revolution of 1905. That revolt was viewed as an important precursor to the Communist Revolution of 1917. Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) was an anniversary film for the same struggle.

Pudovkin is known for centering his films around individual protagonists rather than the group protagonists favored by Eisenstein in his first three silent features. Here the hero is Pavel, a young worker and clandestine revolutionary who lives with his drunken father and downtrodden mother. When guns that Pavel has hidden in the house are discovered, the mother naively betrays her son to the police. He is imprisoned. After a prison break, Pavel joins a protest march, and his mother, now converted to the rebellion, sees him mowed down but carries the flag onward.

Pudovkin’s style is already fully formed here. It’s very flashy, employing the usual fast cutting and depending on highly unconventional ways of framing shots. Pavel’s escape from prison, for example, contains a bird’s eye view as he climbs down some railings to help his comrade put a guard out of commission (above) and a shot during Pavel’s trial uses one of the director’s favorite compositions, shots of police or soldiers seen past their horses heads.

Pudovkin also tends to use imagery of nature to symbolize the revolutionary impulse, as in the famous breaking up of ice on a river during the prison break and protest march. Rivers and lonely trees against low horizons appear in all three films, and the escape over ice floes returns in Storm over Asia (see bottom image). Such techniques perhaps help explain why Pudovkin was the most popular of the major Montage directors.

Given the importance of having these three films available, I hate to find fault. This print of Mother is simply the old Blackhawk/Image. It’s certainly acceptable, but a restoration of Mother, and as we shall see below, The End of St. Petersburg remains to be done. That better prints exist is shown by the illustrations I used in the 1926 entry linked above, which were taken from a 35mm archival copy.

The End of St. Petersburg

For many film fans, The End of St. Petersburg is perhaps the least emotionally involving of these three films. Pavel in Mother and the unnamed Mongolian hunter in Storm over Asia are appealing characters, friendly, brave, and ready to stand up to imperialists, soldiers, and police–and both the victims of flagrant injustices. The unnamed peasant who is at the center of The End of St. Petersburg is initially an ignorant, selfish young man. In a time of famine shortly before World War I, he goes to the city in search of work and becomes a scab, working at a large factory during a strike.

The peasant is friends with one of the workers who fomented the strike, and, echoing the actions of the mother in the earlier film, naively betrays the man to the management of the factory. Once the war breaks out, the peasant stolidly suffers through the entire conflict at the front. Only late in the film does he realize his folly and join the Bolsheviks in the 1917 attack on the Winter Palace. This ends the period when the city was named St. Petersburg.

The peasant is also not in the film nearly as much as the central characters of the two other films. Instead of a compact dramatic narrative, Pudovkin takes us from an era in which the stock market rules society through the war–also waged for the benefit of capitalists–to the Winter Palace attack of October, 1917. The peasant weaves through this, but there is no real point-of-view figure.

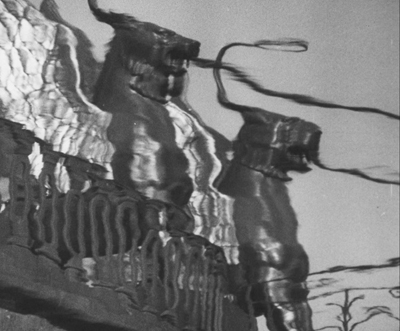

The End of St. Petersburg is a marvelous film nonetheless. In his survey of revolutionary progress, Pudovkin’s flashy style is even more self-assured. In a sense, the city becomes the central symbolic source, with the statues for which St. Petersburg (as it is now again known) is famous representing the power against which the Bolsheviks revolt. The opening scene includes a remarkable series of shots, not of the famous landmarks, but of their reflections in the city’s canals, filmed and then shown upside down, as if the city is shimmering with the weakness that will soon bring down its rulers. The image above shows the griffins holding the cables for the well-known suspension pedestrian bridge, the Bank Bridge.

There are fascinating parallels to Eisenstein’s October, which came out a year later. Both films were among three made to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Revolution. The End of St. Petersburg and Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October were finished and released in the anniversary year, but Eisenstein’s was not. Pudovkin and Eisenstein shared a fascination for the rich Tsarist trappings of the Winter Palace, which were, according to them, enjoyed by the short-lived Provisional Government and its supporters. Certainly The End of St. Petersburg contains some beautifully composed and lit shots of decadent luxuries surprisingly similar to those Eisenstein filmed. (See top.)

The print shares the cropping problems that I pointed out in my 1927 post including The End of St. Petersburg. Since this version is, like earlier releases, based on a 1960s Gosfilmofond “restoration” that sliced off the left of the frame to make room for a recorded soundtrack, all of the shots are too square. I was frequently aware that the frame was simply too close, eliminating part of the image. (The lady in the image at the top was originally more centered in the composition.)

As if to compensate for this problem, the visual quality of this print is startlingly good, as the images immediately above and at the top show. The clarity of the images is actually better than that of the restoration of Storm over Asia. I cannot resist showing another example. Here, in the final attack on the Winter Palace, there is an amazing precision of the lighting in picking out each member of the group of soldiers waiting for the signal to launch the offensive.

We still need a restoration of this film with the full width of the original. In the meantime, however, this version is a substantial improvement over earlier video releases.

Storm over Asia

Pudovkin completed his survey of the creation of the revolutionary struggle with an unusual choice: to set his story in one of the countries that would become close allies of the USSR. It takes place in the early 1920s in Mongolia, where White Russian forces were battling the Chinese for domination. The Bolsheviks formed an army in Mongolia and ultimately helped the country win its freedom. (Pudovkin distorts history by making the imperialist government British.)

The Mongolian hunter is played by Valerii Inkhizinov, a Mongolian citizen who had studied under Lev Kuleshov alongside Pudovkin. His character is cheated by British agents who cheat him out of the fair price for a rare, valuable fox fur (above). His retaliatory attack makes him a fugitive, and he joins a partisan group of Bolsheviks in the mountains simply in order to survive. He is eventually arrested and shot, but a document he carries seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. Nursing him back to health, the British officials exploit this connection to their own advantage. Ultimately he rebels. A final fantasy sequence has him leading at attack by partisans as a huge tempest symbolically sweeps away the British army

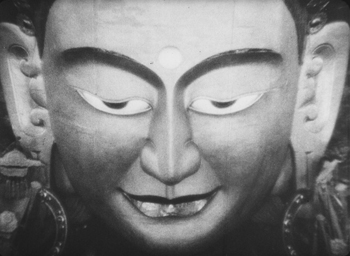

There are virtuoso passages of editing. One comes when he rebels against being cheated over the price of his rare fox fur. Another comes at the end, during the symbolic tempest. In between, Pudovkin often follows a convention of Montage filmmaking, breaking scenes into multiple shots. When a British official and his wife visit a local temple, Pudovkin strings together five increasingly close views of the face of a large statue.

Although the three films have no overlapping characters or social situations, they play very well as a trilogy.

This Blu-ray pair of discs is not a perfect restoration of the three films, but it is so much better than what was available before that this becomes a vital addition to any collection that purports to covers the basic historical classics of the silent cinema.

The set includes several informative extras, including a booklet essay by Amy Sargeant, author of two books on Pudovkin, and two commentaries by present and past curators at George Eastman House: Peter Bagrov on Mother and Jan-Christopher Horak on Storm over Asia. Some short videos analyzing Pudovkin’s editing and showing 1920s footage of St. Petersburg are also included.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley authored an in-depth book-length study, The End of St. Petersburg (I. B. Tauris, 2003).

Storm over Asia (1928)

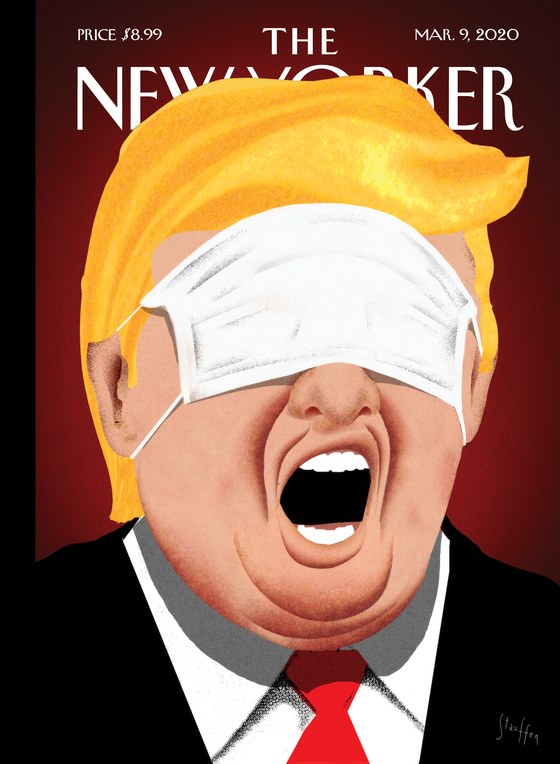

Republican motto: “Government doesn’t work. Elect us and we’ll prove it.”

From today’s New York Times story: “Trump Resists Pressure to Force Companies to Make New Coronavirus Supplies,” by Katie Rogers, Maggie Haberman, and Ana Swanson (20 March 2020).

Some of Mr. Trump’s advisers have privately said they are adhering to longstanding conservative opposition to big government, a view that reflects the administration’s conflicted view of how it should handle a crisis unlike any a modern president has faced.

“First of all, governors are supposed to be doing a lot of this work, and they are doing a lot of this work,” Mr. Trump said to reporters on Thursday. “The federal government is not supposed to be out there buying vast amounts of items and then shipping. You know, we’re not a shipping clerk.”. . .

Not all of Mr. Trump’s advisers subscribe to the theory that the federal government should be as hands-off as possible. Some of his aides believe there needs to be a shift toward using the law and have suggested this to the president.

As the threat of the coronavirus has worsened, officials leading the Trump administration’s response have resisted setting priorities in favor of letting private companies determine their own roles, a stance that has confounded Mr. Trump’s critics but which officials say is a small-government approach that the president’s advisers prefer.

But people familiar with the administration’s actions say the administration is still trying to figure how industry supply chains operate, which companies could produce additional products, and what kind of subsidies they may need to offer . . . .

In a call held with Mr. Trump at the Federal Emergency Management Agency headquarters on Thursday, a group of governors stressed to him that they were struggling to address the staggering demand for equipment and supplies.

At one point, Gov. Kristi Noem, Republican of South Dakota, grew frustrated as she expressed to the president and members of the task force that state officials had been working unsuccessfully with private suppliers.

“I need to understand how you’re triaging supplies,” Ms. Noem said. “We, for two weeks, were requesting reagents for our public health lab from C.D.C., who pushed us to private suppliers who kept canceling orders on us. And we kept making requests, placing orders.”

She added: “I don’t want to be less of a priority because we’re a smaller state or less populated.”

Mr. Trump promised her that would “never” happen before Ms. Noem’s telephone line was disconnected.

When Hollywood ruminates: Calm after THE MORTAL STORM

The Mortal Storm (1940).

DB here:

We don’t usually think of classic studio cinema as particularly contemplative. But many films open up spaces for quiet reflection on what we’re seeing, or have seen. In the 1940s, that tendency owed a good deal to the ways that Hollywood became, to put it roughly, more novelistic.

Movies had been based on novels for many decades, but in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, I claimed something more specific. I think that many 1940s filmmakers became more acutely aware of sound film’s capacities for manipulating time and point of view. These are novelistic techniques par excellence, distinctly different from the largely “theatrical” conceptions of presentation that we find in most studio cinema of the 1930s. Films turned inward, probing perceptions, memories, and dreams. If you need a storytelling twist, one journalist cracked, just call it psychology, and it will get by.

Of course, there are plenty of precedents for time and POV shifts in early decades. Still, I wanted to show that between 1939 and 1952 many major options emerged and were developed in ambitious directions. The results left a legacy. Today, when flashbacks are common and we easily grasp elaborate shifts in viewpoint, our films rework the possibilities refined and consolidated in the 1940s.

One stretch of the book considered some films from early-to-mid 1940 that offered glimpses of innovations we’d see in later years. Married and in Love, One Crowded Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, and Edison, the Man previewed techniques that would dominate the next decade. Particularly chock-full of storytelling ideas, I argued, was Our Town, a daring transposition of 1930s theatrical devices into the key of cinema.

Missing from my roster, though, is The Mortal Storm, a film that went into release in June of 1940. I had neglected to rewatch it when writing the book. A couple of weeks back I caught up with it during a screening at our Cinematheque. Restored by UCLA, it fairly shimmered off the screen.

How could I not have remembered the stunning closing sequence? It’s a bundle of narrative strategies that would get elaborated in the years to come. And it achieves its effect from being somber, slow, and based on human absence. In this epilogue, the movie pauses to think.

To talk about this passage and its counterparts, I have to parade plenty of spoilers. Sorry. But at least you get video.

Emptying the nest

The Mortal Storm.

The plot starts in Germany at the moment of Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Elderly Viktor Roth is a much-loved Jewish professor of medicine. His household includes his stepsons Otto and Erich, his wife Emilia, and their daughter Freya. Two other young men are close to the family: Fritz, who aspires to marry Freya, and Martin, a farm boy training to be a veterinarian.

Otto, Erich, and Fritz become enthusiastic Nazis, but Freya draws closer to Martin, who quietly resists the growing bigotry in their small town. Professor Roth is arrested and killed. Martin and Freya, now deeply in love, try to escape by ski to Austria. A squad of soldiers, under Fritz’s direction, fires on them. Freya is killed.

In the crucial scene, Fritz returns to the family home to tell Otto and Erich.

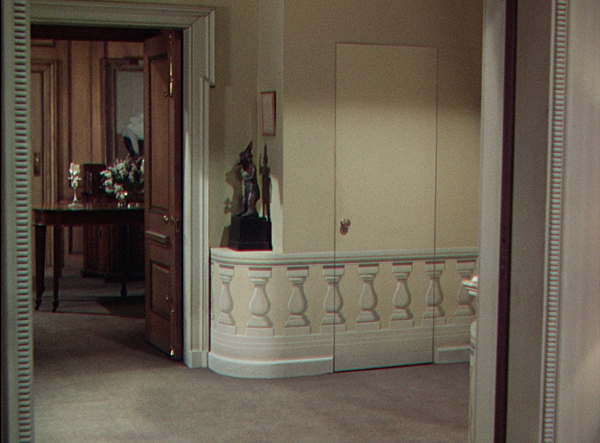

The sequence blends several narrational choices. Most obvious is the camera movement that seems to drift off on its own. It is, we might say, semi-subjective. It suggests Otto’s slow walk through the now-empty home, but it isn’t clearly marked as his optical POV. The opening stretch of the shot shows him pacing more or less obliquely to us, before the camera pans and tracks to the table and beyond.

The framing insistently keeps Otto offscreen. Only the sound of his footsteps and pauses suggest that he’s present, off left or behind us, at each station of the shot.

As the camera drifts along, we get auditory flashbacks to earlier scenes, three at the table, and one echoing the Professor at his lectern. Flashbacks are characteristic features of 1940s cinema, and purely auditory ones will come into prominence, as in The Fallen Sparrow (1943). Since we’ve seen the action these flashbacks evoke, they’re as much flashbacks for us as for Otto. Indeed, Otto has been a minor character in the story. His walk triggers them, but his absence from the frame makes it easier for us to project our memories onto these spaces.

The transition among the flashbacks prepares for Otto’s defection. The voice shifts from Freya, whose death Otto is grieving, to the men challenging authority. We hear Professor Roth urge youth forward, and Martin advocating peace and free thought. These later moments seem to crystallize Otto’s change of heart. Dwelling a bit on the statuette of Youth carrying the torch of knowledge suggests that Otto may become inspired to take up his father’s commitment to humanism.

At the climax of the shot, the camera frames the staircase (another icon of 1940s cinema) and starts to back up. This can hardly be Otto’s optical viewpoint. The rapid footsteps suggest that he has left the house by striding out, as it were, behind us. The sound of a closing door confirms our inference. He has left us behind.

As he does in the final moments, when Otto’s flight is depicted as footprints in the snow. Perhaps, now that he has become revolted by the cruelty of Fritz and the Nazi regime, he will take up resistance in Martin’s spirit.

Accompanying the shots of the footprints is the voice-over narrator whom we heard at the film’s start. (Such narrators proliferate in 1940s movies.) His speech, from a poem called “The Gate of the Year,” echoes the visuals: a man “at the gate,” the prospect that one may “tread safely into the unknown.” In giving up Nazism, Otto is giving up home.

The camera tilts up to show the empty house. The snow-encased home is quite different from the bustling view we saw at the film’s start, when the postman delivered gifts for Professor Roth.

Hitler has destroyed the family. Still, as the snow buries the footprints, the narrator urges that divine guidance can provide safety for Otto’s escape, and perhaps a decision to fight Nazism.

We don’t normally think of MGM as a hotbed of cinematic innovation in the studio years. But the company had its moments (here and there), and this is one of them. The Mortal Storm‘s play with time (flashbacks, the solemn duration of the house tour) and viewpoint (Otto triggering some bits of remembered dialogue) resembles what we might get in a psychologically slanted novel of the time. We’re given a few minutes to breathe deeply and think about what we’ve seen, and to build up expectations about what Otto may do.

The house as memory vessel

The Miniver Story (1950).

One section of Reinventing Hollywood analyzes Enchantment (1948), a film narrated by a house. The house presents itself as a cozy repository of the memories of several generations. More generally, houses are powerful images in 40s films; think of Tara, Manderly, the estate in Dragonwyck, and the Gothic mansions of Jane Eyre, Gaslight, and The Spiral Staircase. Often they’re presided over by ominous portraits, as Steven Jacobs and Lisa Colpaert have shown.

One lesser-known example is House of Strangers (1949), directed by Joseph Mankiewicz. This story of an Italian immigrant who has become the head of a big bank is framed by his son Max returning to their massive home. The bulk of the film is given in flashback, but the flashback is launched by a wandering camera accompanied by “M’apparti tutt’amor” (from the opera Martha) playing on the phonograph. After a trip up the stairs we are taken via dissolve to the patriarch singing it in his bath.

The plot’s central section treats the lyric (“You all seem to love me”) with doubled implication: Gino’s reckless loans endear him to his customers, but his sons resent his power over them. The long flashback ends at Gino’s funeral, passing from the portrait in the past to the phonograph and to his son Max, brooding under the looming picture.

The huge Minafer mansion is practically a character itself in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). One of Welles’ late script versions envisioned a climax in which George, distraught by the shabbiness of their neighborhood, would pass numbly through the house, and our sense of it would be given through his eyes.

145 FULL SHOT of the Amberson Mansion, seen from behind George who is standing in front of camera. He starts walking toward the mansion. CAMERA FOLLOWS, moving faster than he does and soon is so close to him that his body creates a dark screen for a DISSOLVE TO:

146 CAMERA is on the steps of the Amberson Mansion, MOVING up to the door and STOPPING. George’s hands enter the scene, insert a key in the lock, turn it —

147 On the Narrator’s words, “move out” the door opens and CAMERA MOVES thru it into the house.

MOVING SHOT as CAMERA WANDERS SLOWLY about the dismantled house — past the bare reception room; the dining room which contains only a kitchen table and two kitchen chairs, up the stairs, close to the smooth walnut railing of the balustrade. Here CAMERA STOPS for a moment, then PANS down to the heavy doors which mask the dark, empty library. HOLD on this for a short pause, then CAMERA PANS back and CONTINUES, even more slowly, up the stairs to the second floor hall where it MOVES up to the closed door of Isabel’s room. The door swings open and we see Isabel’s room is still as it always has been; nothing has been changed. FADE OUT

This passage is strikingly similar to what we see in The Mortal Storm. True, the cues for George’s optical viewpoint are more explicit than what Borzage gives us for Otto. But Welles is subtler along another dimension. He counts on our remembering earlier scenes without benefit of auditory flashbacks. The camera revisits the reception area we saw during the ball, the dining room where George challenged Eugene Morgan, and the staircase where George and Fanny quarreled, before coming to rest in Isabel’s room, where we saw her waste away and die. We are asked to supply our own flashbacks.

Some of this POV passage might have been filmed, but it wasn’t retained in Welles’ final version, even before RKO’s mangling. In the film as we have it, only Welles’ lead-in and conclusion remain. The narrator supplies a moving-camera montage, as George registers the changes in Amberson Avenue.

The street sequence ends in darkness and tracks back from George kneeling at the bed begging forgiveness. The fact that the shot starts from his darkened head reinforces the subjectivity of the montage.

Welles’s handling is novelistic in the sense of wrapping a character’s flowing impressions inside an omniscient verbal commentary using free indirect discourse (“Tomorrow they were to move out”). George’s moments of rueful meditation are moments for us as well.

Like the narrator that closes The Mortal Storm, this voice is external to the story world. But the same house-haunting effect can be achieved by a narrator who lives in that world. Coupled with the wandering camera, this can turn our view of a scene in the present into a view of the past–or of an eternal future.

The example I have in mind is from The Miniver Story (MGM again, 1950). In Reinventing, I analyze a sequence that creates layers of time: Clem Miniver’s voice-over in our present, an image of he and Kay in the past, and references in the commentary to periods still earlier than what we see. (The clip of this sequence is online here.) At the end of the film, after the Minivers have married off their daughter Judy to Tom, they must face Kay’s impending death from cancer.

The final sequence shifts from the day of the wedding to a kind of timeless realm in which Kay’s spirit lives on. Again, camera movement suggests an invisible presence.

By 1950, we’ve had several permutations. The camera wanders without verbal narration (music alone in House of Strangers). It does so with auditory flashbacks (The Mortal Storm). It does so with a nondiegetic (external) narrator (The Magnificent Ambersons). And it does so with a diegetic (story-world) narrator (The Miniver Story). I try to show in the book that 1940s filmmakers swiftly expanded, even exhausted, menu options involving many storytelling techniques.

Trust Hitchcock to give us yet another variant, and in a tour de force at that.

Enough rope

In the eleven shots of Rope (1948), set almost completely in an apartment, the camera’s peregrinations are usually motivated by character movement or simple track-ins and track-outs. At the climax, though, the camera cuts loose. Sort of.

Brandon and Phillip have strangled their friend David and hidden his body in a chest in their living room. They’ve ghoulishly used the chest as a buffet table for their afternoon party. After the party, one guest, their prep school teacher Rupert Cadell, has returned. He suspects that something bad has happened to David. Rupert challenges the pair and sketches out how they might have murdered their friend.

His reconstruction isn’t wholly correct. David wasn’t bludgeoned, and apparently the armchair played no role. What’s fascinating is that the camera supplies a hypothetical, virtual flashback. As in our earlier examples, David becomes an invisible guest, summoned up by the mobile frame.

The camera traces out the action Rupert posits, emphasizing the hall closet (where Rupert earlier discovered David’s hat) and edging eventually toward the chest. At that point Brandon steps in, with his hand tensing around the pistol in his pocket. He stands in front of the drinks table.

That’s the climax of the shot. Cut to a shot of Rupert. He seems to intuit that he should avoid mentioning the chest, so he proposes that they might have carried the body out of the building. As the camera traces out that possibility, Brandon steps back into the frame to confront Rupert.

Here I think Hitchcock made a mistake. At the end of the first shot, Brandon and his pistol are quite close to Rupert, near the drinks table. But in the followup shot, he’s not visible when the camera pans left past the table to enact the scenario Rupert is considering. Brandon would have had to skip backward like the Road Runner to get as far away as he is when he steps back into the frame in the second shot.

Still, the important effect is the representation of Rupert’s thinking. Goaded by Brandon, he ponders how the crime might have been committed, and the camera carves into space to reveal the scheme he conjures up. A sort of flashback? Yes, but an unreliable replay, left largely to our imagination. Semi-subjective? Yes, since when we cut to Rupert he seems to be staring down at the chest. Yet the camera is too free-ranging to be purely Rupert’s optical POV. He’s not moving around, as Otto is in the Mortal Storm sequence.

In this most “theatrical” of movies, Hitchcock manages to give us a verbal-visual flow that is something like a cinematic equivalent of the novelist’s conditional perfect tense. If Brandon and Phillip had killed David, they could have done it this way. The camera enacts a speculative train of thought. Call it psychology.

One thing I shouldn’t ever forget: Hollywood in the Forties is a booming rush of visual, auditory, and narrative ideas. In the approximately 5,655 features released in the period I marked off, there are surely many other startling instances of creative craft. I’ll keep looking.

Thanks as ever to our Wisconsin Cinematheque for fine programming under the auspices of Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser and excellent projectionist Roch Gersbach. Thanks as well to Joe McBride for sharing material on The Magnificent Ambersons. More on Ambersons can be found here and here.

The Mortal Storm‘s “novelistic” final moments owe nothing to its source, Phillis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938). An earlier version of my ideas about Enchantment are here.

Chapters 4 through 6 of Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood offer a careful survey of creative choices facing filmmakers of the period, along with explications of their “practical theories” about cinematography. After writing this entry, I learned that Patrick has also made a fine video essay on the Ambersons sequence.

For earlier blogs on related subjects, see the category 1940s Hollywood.

PS 2 March 2020: Patrick Keating reminds me of another 1940 release I should have mentioned: Hitchcock’s Rebecca. When Maxim narrates his confrontation with Rebecca, the camera moves autonomously to “replay” the scene. It anticipates my Rope example, except that Maxim is recounting what really happened, while Rupert is sketching out his (partially inaccurate) reconstruction of David’s death. Still, though, it’s another variant on an emerging pictorial convention. Thanks, Patrick!

PS 2 March 2020, later: Thanks also to John Belton, who writes to remind me not only of the Rebecca scene but a comparable camera movement in Under Capricorn. Crowdsourcing works.

Rope (1948).