Archive for June 2020

Nero, Archie, and me: Preface to a new web essay

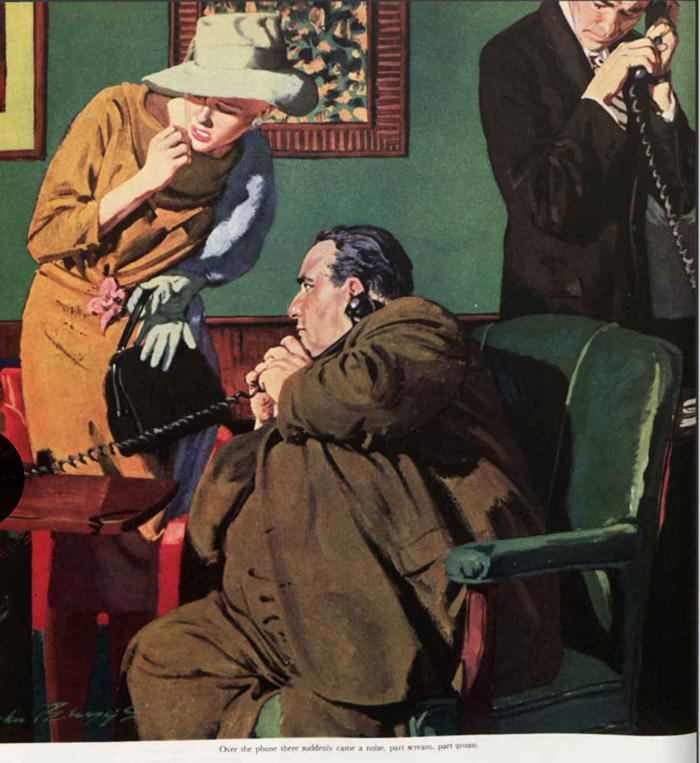

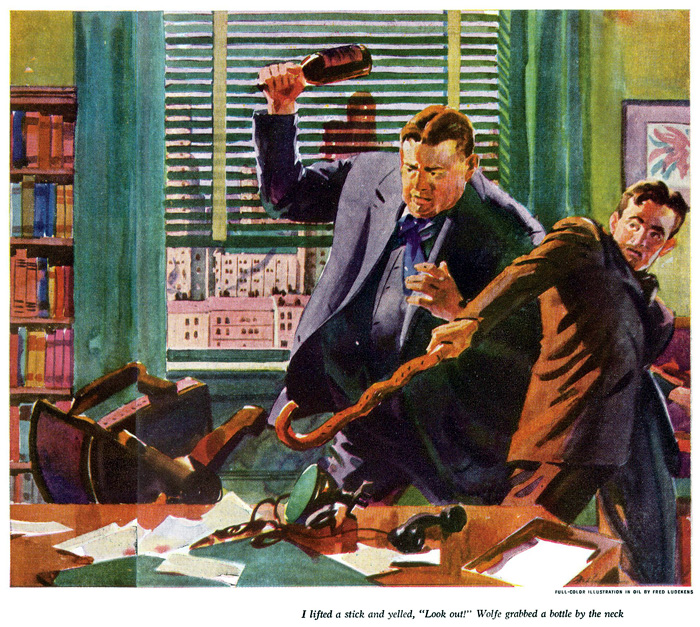

“Frame-Up for Murder” (“Murder Is No Joke”), Saturday Evening Post (21 June 1958).

DB here:

“It is impossible to say which is the more interesting and admirable of the two.” Thus Jacques Barzun on Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, the characters created by Rex Stout. I’d go farther. For me they are among the outstanding figures of American fiction, and Stout is one of the finest American writers of the twentieth century.

Wolfe and Archie are detectives, and Stout wrote mystery fiction. But that just goes to prove that genre work isn’t just good “of its kind.” It’s often good, period.

Stout started as a pulp novelist. He moved to what we now call literary fiction before pursuing a variety of more mainstream genres. He wrote quasi-experimental novels (one is told backward), comic romances, lost-world sagas, and a political thriller, The President Vanishes. (Stout admitted that Wellman’s film version was better than the book.) He introduced several other detective protagonists, but he wisely concentrated on Wolfe and Archie, whom he launched in 1934 and traced through dozens of adventures until his death in 1975.

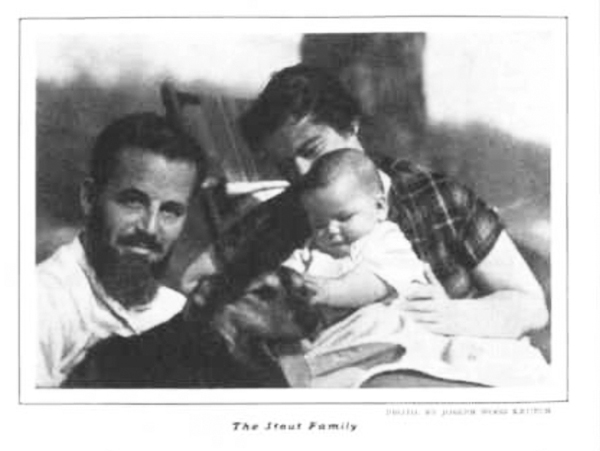

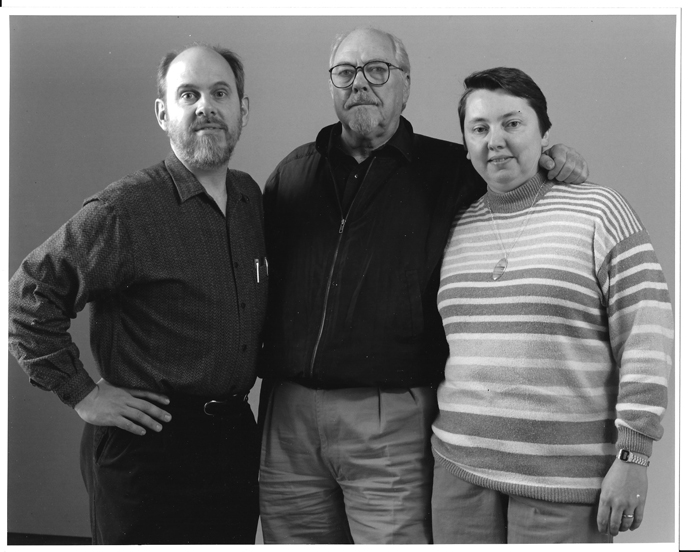

Here is Stout with his wife Pola and daughter Barbara in 1935.

Are these stories still read? I hope so. When I quizzed the grad students in my seminar this spring, most seemed unaware of what for me–and, I think, other baby boomers–were major figures in popular culture. It’s partly because the ancillary media never did a good job spreading the word. The film Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) was weak, in keeping with the general failure of 1930s films to capture the strengths of supersleuths like Philo Vance and Ellery Queen. (Better were the Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan vehicles.) During the late 1990s, Bantam reprinted the books in quality paperback editions, with introductions by other writers (Westlake, Lippman et al.). There was a solid cable-TV series (A Nero Wolfe Mystery) back in the early 2000s, with a trying-a-bit-too-hard Timothy Hutton as Archie but a near-definitive Wolfe in the form of Maury Chaykin. But that’s all pretty far back now.

O well . . . . If Perry Mason can come back, maybe Wolfe and Archie can too. And they won’t be scruffy and unshaven. Archie explains: “I was born neat.” So was his prose.

Today, I’m posting a long (22,000 words!) essay on Wolfe and Archie in an effort to show some reasons they and their creator matter. Background follows below.

Research? Say rather, obsession

Like most academics, I try to pour my obsessions into my research. My interest in mystery stories (fiction, film, even theatre and TV) is surfacing in my current project, a book studying principles of popular narrative as they emerge in thrillers and detective stories. In a way, the book turns inside out what I tried to do in Reinventing Hollywood. There I traced film techniques to sources in adjacent media. Now I’m looking directly at those media to consider their formal and stylistic strategies, with some consideration of how film shaped and was shaped by them.

My survey covers familiar ground. I consider the classic detective story (the so-called “Golden Age” of Christie, Sayers, Queen, Carr et al.), the hardboiled writers, the suspense thriller, and the crystallization of major techniques in the 1940s (a polemical point with me). Later chapters analyze the heist plot, the police procedural, and particular writers (e.g., Cornell Woolrich, Ed McBain, Richard Stark, Patricia Highsmith). As presently planned, the book ends with an odd-couple pair of chapters: the “puzzle film” trend of the 1990s, and the domestic thriller of recent years (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train). Some chips from the workbench have littered this blog, as the links indicate.

One of my key questions is: What has enabled readers and viewers to welcome the sort of extreme complexity that we find in movies like Pulp Fiction or Memento? We’re all now connoisseurs of narrative intricacy, in not only crime plots but science-fiction and fantasy ones (which actually often rest on mysery premises; see Devs).

Another theme of the book is one I pitched in Reinventing Hollywood. I argued that very quickly “modernist” innovations in fictional technique were channeled into something more moderate and middlebrow. It’s there that wider audiences gained proficiency in handling flashbacks, ellipses, plunges into subjectivity, opaque exposition, and other challenges to linear storytelling. At the end of the 1920s, while Joyce and Woolf and Faulkner were pushing modernism into ever more recondite byways (Finnegans Wake, The Waves, The Sound and the Fury), other writers were adapting advanced techniques to traditional ends.

Another theme of the book is one I pitched in Reinventing Hollywood. I argued that very quickly “modernist” innovations in fictional technique were channeled into something more moderate and middlebrow. It’s there that wider audiences gained proficiency in handling flashbacks, ellipses, plunges into subjectivity, opaque exposition, and other challenges to linear storytelling. At the end of the 1920s, while Joyce and Woolf and Faulkner were pushing modernism into ever more recondite byways (Finnegans Wake, The Waves, The Sound and the Fury), other writers were adapting advanced techniques to traditional ends.

And traditional genres. I’ll argue that modernist experiments provided some strategies that mystery writers could recast within the bounds of their tradition. Stout’s first two serious novels, How Like a God (1929) and Seed on the Wind (1930) joined the trend toward mainstreaming modernism. By 1930 he had fully absorbed what the 1910s-1920s writers had achieved. What’s less obvious is the mark of modernist writing on his reader-friendly detective stories. Yet one lesson of modernism, I think, is the need to play with language, to “defamiliarize” literary texture. That, I think, is one of the tasks Stout took on in the Wolfe saga.

I had planned to include a chapter on the Wolfe/Archie series, but what resulted was far too long in comparison with its mates. So I’m posting it online as an essay. A shorter version will show up, somehow, in the finished book.

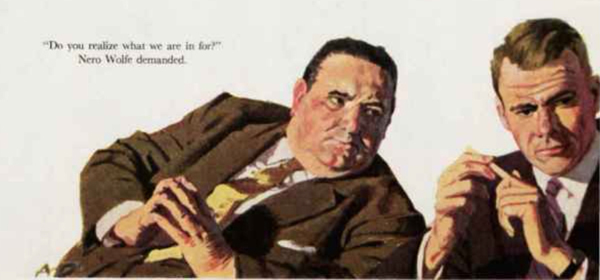

Luckily, thanks to the Internetz, the essay’s web incarnation can include some illustrations from magazine publication of the stories. Since most of the books’ drama takes place in Wolfe’s office, artists are challenged to find nifty ways to show people grouped around a desk.

I hope, then, that fans of the series will find some ideas and information of interest. Above all, I hope what I’ve said here and there will stimulate novices to venture on one of the great exercises in American popular storytelling. If you don’t care for it, all I have to say is: Pfui.

There are many good websites devoted to mystery fiction. The most comprehensive is Mike Grost’s. You should also look into Martin Edwards’ fine blog Do You Write Under Your Own Name? See also the official Wolfe Pack site, full of links and assorted Stoutiana. John McAleer’s biography Rex Stout (Little, Brown, 1977) is vastly informative. Stout was not only a great writer but also a fascinating man.

P.S. 8 July 2020: I’ve just learned that jazz pianist Ethan Iverson has posted on his site “Comfort Food,” a superb appreciation of Nero and Archie’s world. He discusses all the books, and even includes a page of Stout’s FBI file!

Fer-de-Lance, serialized as “Point of Death” in American Magazine (November 1934).

Auteurs by the hour: The Walker Art Center Dialogues

DB:

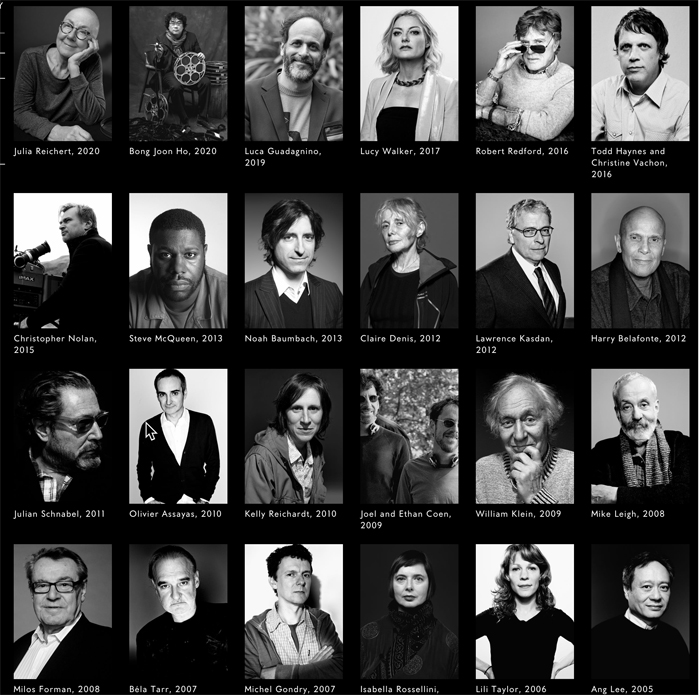

For decades, the world’s top filmmakers have made pilgrimages to the splendid Walker Art Center of Minneapolis. A series of astute curators of film provided a keen public with in-depth conversations about cinema. Now, suitable for a podcast-friendly era, the Center has given the world precious recordings of those discussions. The talent on display is overwhelming. Here’s just the half of it.

Some dialogues are audio only, but many are carefully mounted videos, with stills and clips. The questioners have been chosen from the ranks of archivists, programmers, critics, and academics. (I did one with Altman in 1992.) There are also written transcripts available for download.

In all, this should provide cinephiles with a rich array of ideas and information for years to come: Film history on the hoof. Thank you, Walker demi-gods, for reminding us that the Internet can be benign.

DB and KT with Robert Altman, Walker Art Center 1992.

Another degree of Kevin Bacon: David Koepp’s YOU SHOULD HAVE LEFT

You Should Have Left (2020).

DB here:

Friend of The Blog David Koepp has written and directed a new movie that is premiering online this week. You Should Have Left is in the vein of his earlier, locked-in exercises in psychological horror, Stir of Echoes (1999) and Secret Window (2004). Both a haunted-house story and a disquieting probe into male anxiety, it’s another strong entry from Blumhouse–for me, the most interesting film company out there.

Critics sometimes say that Clint Eastwood is the last really “classical” director working now. Actually, in my view almost everybody remains a classical director to some extent. Still, the term holds especially good here. David’s handling of this scary chamber drama reminds me of the unfussy precision of Polanski in The Ghost Writer. In fact, one shot recalls the famous partial view of Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby. (Doorways are always good spots for tricky framing.)

More generally, David isn’t ashamed to invoke all the creepy conventions of the Old Dark House, suitably updated. He lays out the house’s space tidily and then disorients us about exactly where we just were. I think the Dreyer of Vampyr would appreciate the ways in which this PoMo mansion becomes a maze.

Of the other films David has directed, I’m especially fond of Ghost Town (2008) and Premium Rush (2012). And of course his scripts for Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds, and other megapix are models of construction. I also admire his superbly crafted screenplays for Panic Room (another claustrophobic exercise), for the still-too-little-appreciated The Paper, and for the bravura item that is Carlito’s Way.

You Should Have Left is currently available on demand from many cable and streaming services and will eventually show up as part of the offerings of NBC Universal/Peacock.

For more on David’s work, go here, which will lead you elsewhere.

You Should Have Left (2020).

Little stabs at happiness 3: You know, for kids

Iron Monkey (1993).

DB here:

Another entry (apologies to Ken Jacobs) of little things that cheer up lockdown. Previous entries are here and here. This one, unlike a couple to come, is suitable for all ages.

Why do I get a thrill from watching an apparently frail little boy beat the bejeezus out of unkempt bullies? More to the point, why weren’t there movies like Iron Monkey (1993) when I was a tad?

It’s a wing of the Tsui Hark Wong Fei-hung reboot saga that began with Once Upon a Time in China (1991), putting Jet Li on the world map. This installment is directed by Yuen Wo Ping, master choreographer of Crouching Tiger and The Matrix and no mean director himself. It’s a prequel, showing us the young Fei-hung learning his craft from his apothecary father and the mysterious robinhoodish Iron Monkey.

Before the main course, here’s a snack.

This one minute of graceful movement is one minute more than you find in most of our movies today. Do something short, smart, and crisp, and the camera loves it.

To see Young Wong finding his groove, here’s the scene in which he practices some fancy evasion and defense against heavily armed but fatally dumb thugs.

The subtitles provide a whole other level of diversion.

The whole film, featuring Donnie Yen and other Hong Kong stalwarts, is good dirty fun. Versions are available on streaming, but you should avoid the sanitized Miramax release. There’s also a 1977 kung-fu film bearing this English-language title, but its plot is quite different.

Note: The boy Wong is played by a girl martial artist, Angie Tsang Sze-man, who went on to become a wushu champion.

For an update on the situation in Hong Kong, here is a story in the Washington Post.

I write about the art and craft of Hong Kong martial arts movies in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It explains, among other things, why the subtitles are so weird (p. 78).

P.S. 15 June 2020: Thanks to Radomir Kokes (Douglas) for correcting my misattribution of The Transporter to Yuen Wo Ping. It was of course directed by the great Corey Yuen Kwai.