Archive for June 2020

Talking pictures: Wisconsin Cinematheque screenings and podcasts

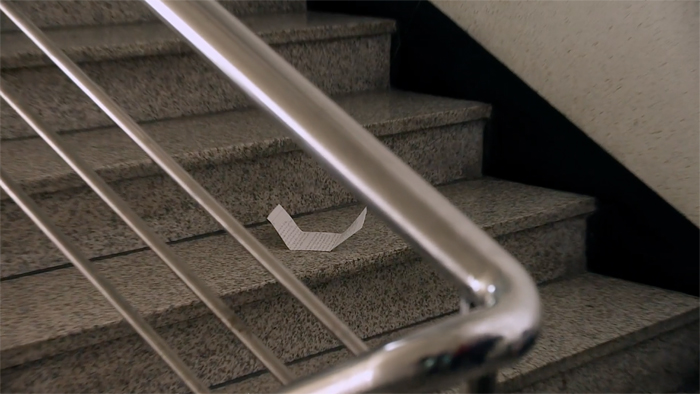

Hill of Freedom (2014).

DB here:

Crises make people resourceful, and the Covid-19 virus has spurred workers in film culture to try new ways to feed movie appetites. The tactics include making films available virtually. Our Wisconsin Cinematheque has joined this movement by offering titles on a weekly basis in cooperation with friendly distributors.

Along with the virtual screenings, the crew of Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King have created podcasts discussing the movies available for viewing. This week’s program is Hong Sangsoo’s Hill of Freedom. You can see it by going here. This ingratiating movie is one of my favorite Hong titles; I reviewed it at Vancouver here.

You can hear Mike King and me discussing Hill of Freedom in our Cinematheque podcast. The series has already hosted discussions with New York Times critic Manohla Dargis and Twentieth Century Fox archivist Schawn Belston. The team has also corralled filmmakers James Runde, Dan Sallitt, Mark Goldblatt, Peter O’Brian, Mary Sweeney, and not least the wonderful Bill Forsyth. Go here for the complete list.

Thanks to Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Jim Healy for setting up this pleasant encounter. Keep in touch with our Cinematheque!

Bill Forsyth has been one of our blog’s best friends, so do check in on our encounters with him: at Ebertfest in 2008 and at Antwerp in 2015. The Antwerp visit led to a fine interview as well.

Tom Paulus interviews Bill Forsyth in the Antwerp Summer Film College of 2015.

“Student film,” exploitation film, indie classic

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley continues to bring out an eclectic and unpredictable series of restored films, from French Impressionist classics to Cinerama films to obscure film noir Bs to early films directed by women, and the list goes on. (Search this blog for “Flicker Alley” and you’ll find many more.)

On May 19, the company released a Blu-ray/DVD dual-format set of Spring Night Summer Night (1967), directed by J. L. Anderson. Anderson is known to film academics primarily as Joseph L. Anderson, the co-author with Donald Richie of The Japanese Cinema: Art and Industry (1959, rev. ed. 1983), the first substantial English-language survey of that national cinema.

In the mid-1960s Anderson was teaching filmmaking at the Ohio University in Athens. He and his students made some 16mm short films for the university. He wanted, however, to give them experience making a professional-level feature on 35mm, shot in the part of Appalachia located in southeastern Ohio, near Athens. Apart from teaching film technique, Anderson showed his students art films, many of them from Europe. He was particularly fond of Italian Neorealism and wanted to apply its aesthetic approach to a story set in the poverty-stricken milieu of Appalachia in the wake of the closing of the area’s coalmines.

Students undertook the cinematography and other tasks. The main roles were cast with experienced actors, while local people filled the minor roles and worked as extras. One of the students, Franklin Miller, was deeply involved in the filmmaking: he co-produced, co-wrote, and co-edited the film. The pair even did sound-effects recording, combining their name as “Joe Franklin” in the credits.

Local color galore

The film deals with a farming family. The father, Virgil, has a son, Carl, by his previous wife, who died in childbirth. Virgil and his current wife Mae are raising their daughter, Jessie, along with four younger children. Carl and Jessie have fallen in love and despite being half-siblings, yield to temptation, leaving her pregnant. Virgil causes strife in the family by trying to find out who the father is and to force him to marry Jessie. Eventually the couple begin to wonder if they are indeed blood relations, given that Mae is obviously having a long-term affair with another man.

Although the story is involving, the main strength of the film is the remarkably rich depiction of life in an impoverished, largely rural area. Absolutely everything, exteriors and interiors alike, was shot on location. A remarkable pair of scenes in a crowded bar was shot in Athens rather than the main tiny town, Shawnee, but the difference is unnoticeable.

The supplements to Spring Night Summer Night reveal that the bar scene extras were gathered by advertising that anyone attending the bar would be given five dollars’ worth of fake money good only at the bar. Given that bottles of beer were twenty-five cents, the unexpectedly large crowd became quite lively. The filmmakers were able to insert staged bits of action–mainly a fight between the jealous Carl and a boy who dances with Jessie–among the spontaneous activities of the local people without any of the extras seeming to take notice.

The cinematography in all the locations is beautiful, as the images above and at the bottom of the entry show. While the cameras were run by filmmaking majors, the result looks quite professional. As Larue Hall, who played Jessie, says in the Cleveland Cinematheque Q&A supplement, “I never call it a ‘student film’ when I talk about it.” Anderson obviously was a good teacher.

One memorable scene displays the filmmakers’ skill. It’s a single take, four minutes and ten seconds, that takes place in a bar. The camera begins behind a man whose face we never see, then arcs around him to focus on Virgil.

Virgil summarizes his life, including its more prosperous days when the coal mines were the main local employer: “Better believe it was different when the mines was working. Made some good money in the pits.” He describes his two marriages and his life in the military and concludes sadly, “You try to live your life right, but it just don’t work out.” The other man, offscreen for most of the shot, never replies. (The scene as scripted would have lasted longer, but the limitation of the camera’s capacities forced a condensation.)

This release was of particular interest to David and me, since we knew the two people most involved in the various phases of making the film. Anderson himself visited the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the 1980s, in his capacity as an historian of Japanese cinema. He did a benshi performance to a silent Japanese film, which was a rare treat. After his studies finished, Franklin Miller got a job teaching production in the University of Iowa’s budding film division. There David and I met him a few years later when we were both graduate students. Neither of us took a course with him, but it was a small division and we got to be friends. He’s now a professor emeritus, living in Ohio with his wife Judy, who served as the “continuity girl” on Spring Night, and did other jobs as well. Indeed, as Franklin emphasizes in the supplements, everyone in the cast and crew pitched in wherever they were needed.

The Making-of

To me, almost as fascinating as the film is a making-of documentary included as a supplement: Behind-the-Scenes of SPRING NIGHT SUMMER NIGHT. (This is listed in the menu as 16mm Behind-the-Scenes Footage.) It includes a commentary track that is a basically a long conversation between one of the people most responsible for the restoration, Peter Conheim, who also edited the 16mm footage from 1965 into this roughly hour-long film, and Franklin.

This is a very recent interview indeed, since Franklin’s part had to be recorded remotely due to the current pandemic. In it, despite the roughly 55-year interval since the completion of the film, he remembers the names of all the people involved and gives a great deal of information about the filmmaking procedures seen being used in the footage.

(In preparing this entry, I got in touch with Franklin after having had no contact for years, and I am grateful to him for providing some additional technical details that I’ve included parenthetically here.)

The footage and still photos were shot by several members of the cast and crew. As Franklin remarks in the commentary, “If nothing else, if you’re making a film in Athens, Ohio, and everyone on the crew is a photographer, one of the things you’re going to get is lots of documentation.” Indeed, there were so many people hovering around filming the filming that often part of what you see is them doing so.

Having been a jack-of-all-trades on this project, Franklin is seen in the film nearly as much as is Anderson. At 25 during the shooting in 1965, he looks very young indeed. Here he is with the owner of the farm which was used as the location (interior and exterior) for the main family’s house.

One reason the film looks so professionally made is the equipment used. The production was able to rent some Arriflex 35mm cameras which were outdated and sitting around the equipment supplier’s shop. (According to Franklin, these were model 2C, and needed a large blimp; they also required AC motors to shoot sync sound: “Anything that looks handheld and sync was dubbed.”) The black-and-white 35mm results look great.

Some shots do look very handheld, particularly a frenetic chase for an escaped rooster inside the farmhouse and the lively barroom scenes. Much of the sound was indeed post-dubbed.

Often, though, the camera was on a tripod or a dolly rolling on platforms made of plywood. See, for example, the frame at the top of this section. That’s Anderson in the short-sleeved white shirt and dark pants, walking along behind John Crawford as Virgil. Anderson often directed in this fashion, staying close to the actors. In the same frame above, that’s Franklin in the white T-shirt pitching in as usual by pushing the dolly (improvised from “a prototype sports car that the King Midget Company (Athens, Oh) had abandoned,” again according to Franklin.) Judy, in a dark sweater, sits on the dolly with her continuity notebook.

There are also some impressive tracking shots alongside a speeding motorcycle, done with the camera on a platform sticking out the side of an open van.

At one point we see the filming of a night scene of Carl and Jessie in the woods, with Carl scuffling with his father Virgil. Franklin remarks on the commentary that they had only one or occasionally two small units for night shoots. He would have preferred to have more of these to cast some fill light on the surrounding trees. (According to Franklin, “The light that the couple walk toward at the end was a 5-minute magnesium flare. Three feet long and four inches in diameter. Just like the silent days. Plus it adds smoke.”) As this frame from Behind-the-Scenes shows, the result was very stark indeed, with the glaring light, ostensibly coming from the headlights of Virgil’s car, placing the characters against a dark void.

The result could be said to be more realistic, as woods at night do tend to be very dark. In some shots, though, the low lighting is artistically impressive as well, notably in an extreme long shot of the couple walking in the distance in a patch of dim light that silhouettes some trees, again surrounded by darkness. (See image at top.)

All in all it’s a lovely film, and a major early example of the low-budget regional cinema that later became a staple of the Sundance Film Festival.

A scuppered release

So why have virtually none of us heard of Spring Night Summer Night, which seemed so destined to become a classic when it was finished and ready for release in the late 1960s? Its world premiere was at the Pesaro Film Festival in 1967, and all seemed well. It was scheduled to show at the 1968 New York Film Festival, but for reasons unknown it was bumped in favor of John Cassavetes’ Faces.

As a result, it found no distributor until Joseph Brenner Associates, which specialized in exploitation films, bought it on the condition that some soft-core sex scenes be added. To save the project, Anderson shot these, and the result was released in 1970 as Miss Jessica Is Pregnant. I won’t go into the details of that apparent ignominious end to a project that had been the result of so much enthusiastic, devoted effort by students and local people. It is dealt with in the program booklet accompanying the Flicker Alley release, as well as a supplement, In the Middle of the Nights: From Arthouse to Grindhouse and Back Again, on the discs. After that, the original negative sat in Franklin Miller’s office, and the film was essentially forgotten.

After decades, an effort to restore and reconstruct the original film was undertaken. Again, the full stories of this difficult endeavor are provided in the booklet notes. Anderson and Franklin both approved two small changes that were made to the original film, making this a director’s cut of sorts. (The changes are described on p. 24 of the booklet.) Anderson is now quietly retired in Florida. He was able to participate in the two supplements, Spring Night Summer Night: 50 Years Later and Cleveland Cinematheque Q&A. Unfortunately his health did not permit him to attend when the film finally received its screening, exactly fifty years delayed, at the New York Film Festival in 2018. (For coverage of that event, as well as a good summary of the film’s history, see Chris O’Falt’s piece on Indiewire–which adds a comma, not in the original, to the film’s title.)

The restoration certainly shows no signs of the film’s troubled history and different versions. It’s a beautiful job, and this release should at last elevate Spring Night Summer Night to the status of classic that it deserved from the beginning.

Peter Conheim was co-restorer of the film, along with Ross Lipman, via the Cinema Preservation Alliance. Peter has sent me information on a second planned restoration: “Joe only made one other feature after SNSN, AMERICA FIRST (1972), but it was never released. I actually hold all the original materials on the film and hope to do preservation on it … assuming I can find the funding. It’s a sort-of follow up to SNSN, though very different in tone. Filmed in color, in the same area, but more like ZABRISKIE POINT than SNSN!” Eminent cinematographer Ed Lachman (True Stories, The Limey, A Prairie Home Companion, Carol, Dark Waters, and many more) began his film career by shooting America First, and he has agreed to participate in the color correction.

Peter also tells me that there was a first pass at preservation by by the UCLA Film and Television Archive back in 2014.

Thanks to Franklin Miller, Jeffery Masino, and Peter Conheim for assistance in preparing this entry.

Little stabs at happiness 2: Short and sweet, in a city on fire

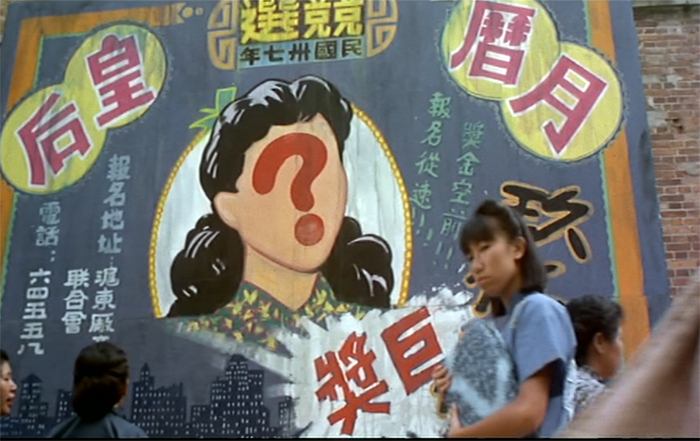

Shanghai Blues (1984).

While US streets pulse with protests against racism and police violence and a fascistic presidential regime, it’s worth remembering that we aren’t alone. Hong Kong has been through this many times, and there the people’s struggle is growing ever more acute. The idea of “burning together” (laam chau) is starting to seem the only option when civil remedies are met by oppression. Hong Kong identity, a palpable force of history, is at stake. As one of my HK correspondents writes: “When it comes it comes. I am sure we won’t just stand here . . . . We will keep fighting for our rights.”

It’s hard to find consolation in these times, but again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs for swiping his title, I offer you a pause to let film art take over. It’s especially poignant in that film, one of Hong Kong’s great contributions to world culture, can seize and hold moments of rapture. All the more ironic that this film, Shanghai Blues, is about ordinary people fleeing the mainland for the British colony to the south.

It’s as goofy a comedy as Tsui Hark ever made, but as usual with Tsui in his prime, it brims with energy. At the end of World War II, Doremi (Kenny Bee), an aspiring composer, is searching for the woman (Shu-shu, Sylvia Chang Ai-chia) he met and lost in a 1937 bombardment. But he’s living unwittingly in the same building she’s in. Meanwhile, a naive young woman (Sally Yeh Chia-wen) arrives from the country trying to make her way in the city. Over all hover two contests: a Calendar Queen prize, and a song competition.

Here’s the sequence that always makes me grin. Doremi comes out at night to play his composition. I really admire how Tsui synchronizes the rhythm of the visuals (especially Sally’s pop-up frame entrance) with the music.

Unfortunately, the film isn’t easily available. There’s a goodish French DVD, but no streaming source I know of. (My clips come from the laserdisc.) If you want more, and at the risk of a supreme spoiler, I offer you the climax, a reprise of the balcony moment that yields a happy ending and a bittersweet time loop.

This virtuoso scene is another example of Tsui’s skillful use of music, cutting, and composition. The movie may be set in Shanghai, but its shameless vivacity is pure Hong Kong.

Here are some resources if you want to help the people of Hong Kong. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for this link. Yvonne blogs, captivatingly, at Webs of Significance.

I write about Tsui, and Shanghai Blues, in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment.

Shanghai Blues (1984).