PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

Sunday | August 9, 2020 open printable version

open printable version

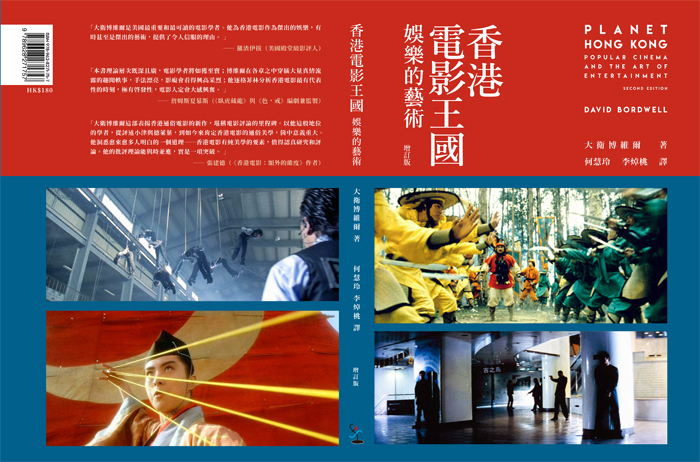

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.