Archive for February 2021

Historical film colors: A guest entry from Barbara Flueckiger

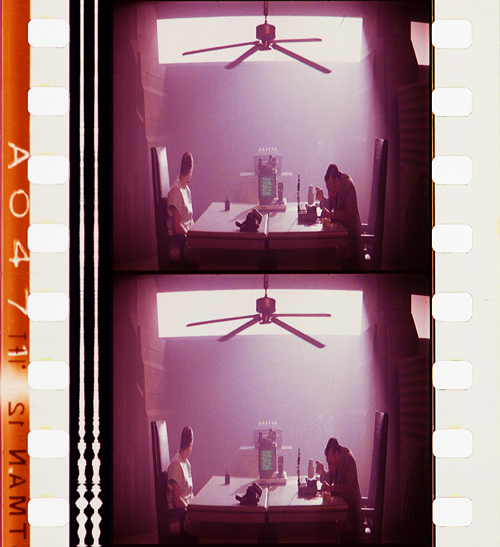

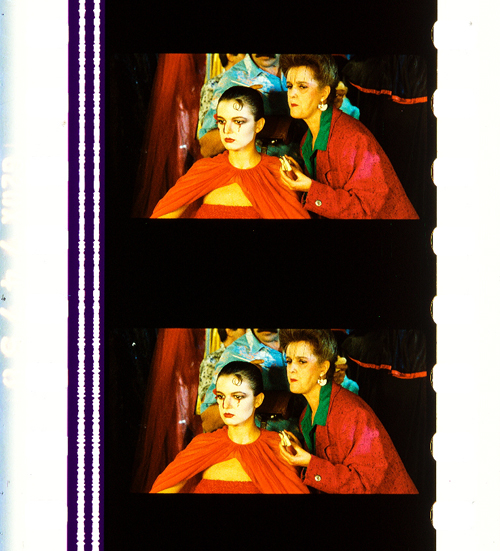

Trois couleurs: Bleu (France/Poland/Switzerland 1993, Krzysztof Kieślowski). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the Agfa Gevaert safety print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Kristin here:

To the general film-going public, old films are in black-and-white. They may be vaguely aware that before The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, color film was invented.

The history of film color, however, is vastly more complicated than that. Prof. Barbara Flueckiger, of the University of Zurich, has devoted much of her career to studying that history. With Eva Hielscher and Nadine Wieylisbach, she co-edited the 2020 collection, Color Mania: The Material of Color in Photography and Film (Zurich: Eds. Lars Müller/ Fotomuseum Winterthur). Barbara has also spent the past decade leading a team who have created a recently inaugurated and invaluable website that acts as a boundless resource for information on color processes.

We are delighted that Barbara has accepted our invitation to write a guest blog entry for us. She describes the website and gives a succinct outline of the history of film color, loaded with beautiful illustrative frames. Most of these were taken from original archival prints that reveal how seldom–especially in this age of digital home video–we see color films as they looked when they were released.

Barbara Flueckiger

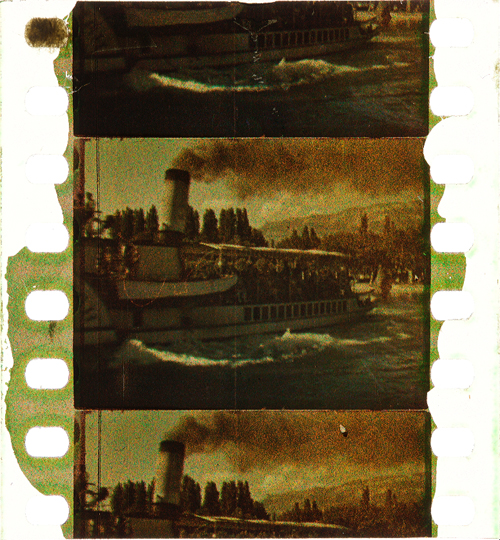

From their earliest days, films were colored. During the first three decades, most color imagery was obtained by applying dyes to black and white prints, either by hand, through stencils, or as tinting and toning of the filmstrips. From the beginning, however, many ideas emerged to capture colors directly on film as so-called mimetic colors. That could be done either by optical and mechanical means, such as colored rotary filters, or by chemical interventions, often in combination with optical configurations of cameras. Several hundred analog color processes and film stocks were invented in the first 100 years of film history. Many of them were never successful commercially.

Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs (France 1902, Ferdinand Zecca). Credit: BFI National Archive. Photograph of the stencil-colored nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

This history is largely unknown to the general audience as well as to many film scholars and historians.

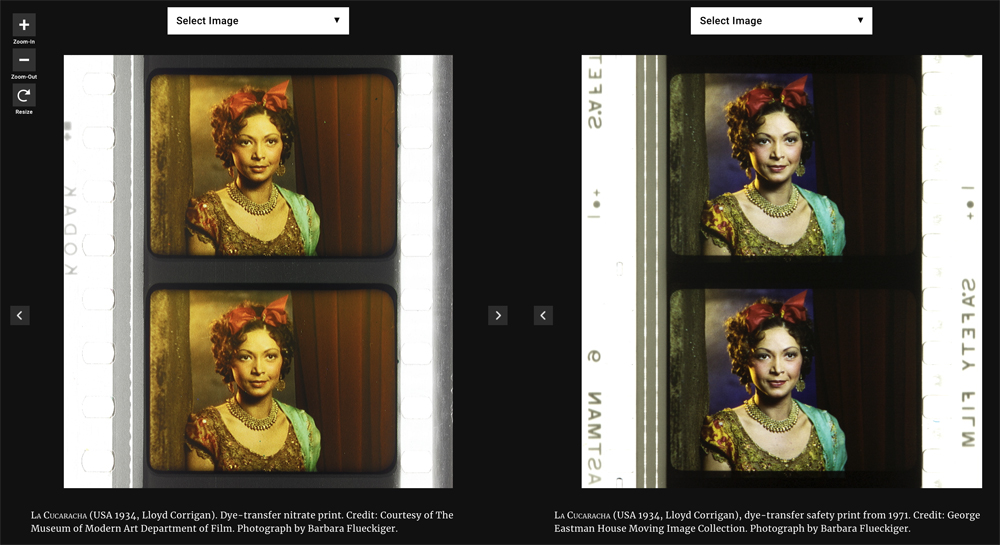

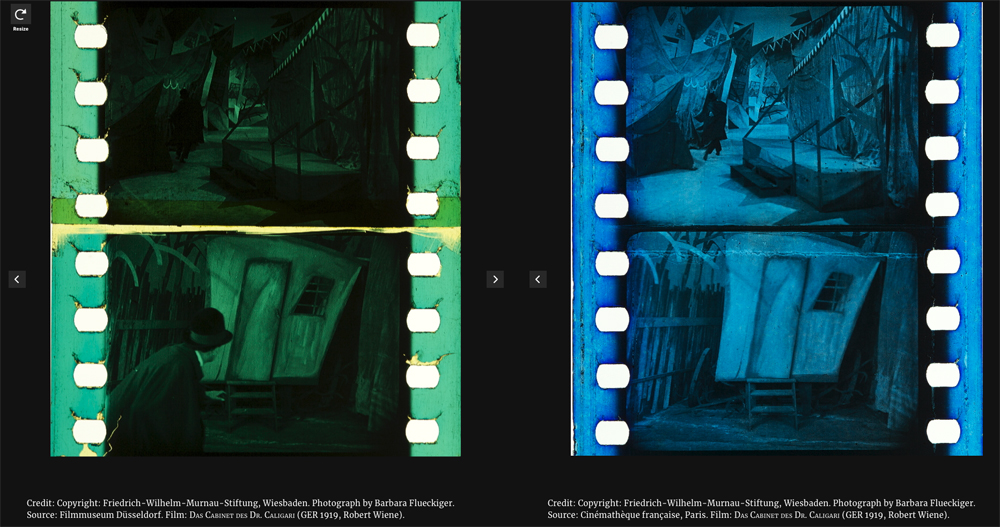

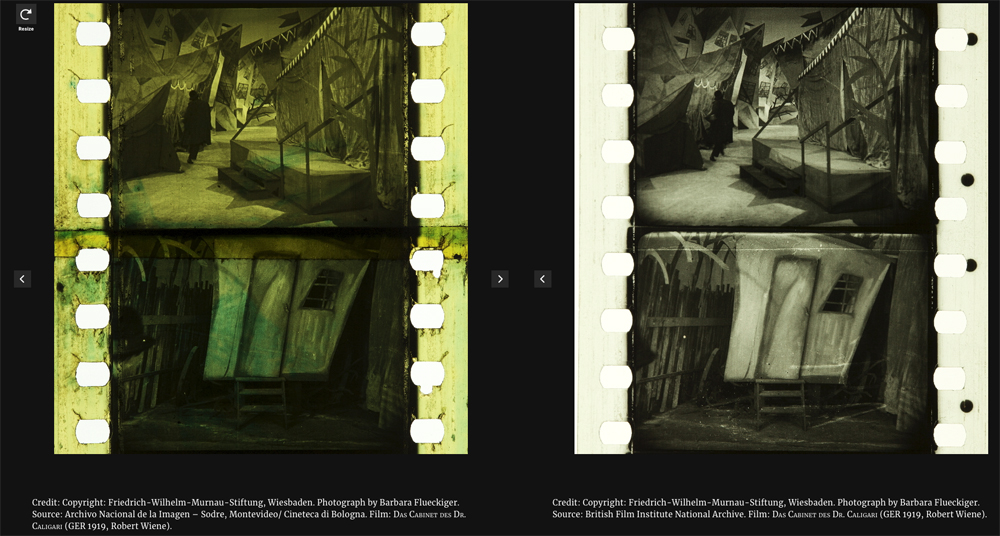

To close this gap in our knowledge, in 2011 I started to develop the Timeline of Historical Film Colors, a comprehensive web resource. I wanted to document the development of film colors from their prehistory in still photography in the 19th century to the latest developments in the analog domain. As of 2021, the platform contains hundreds of primary and secondary sources, patents, links, selected analyses, physical measurements and downloads, as well as more than 23,000 photographs of historical film prints and negatives. These items provide film historians, researchers, archivists, curators, film restorers and students easy access to a vast array of information. A tagging system connects the entries, galleries, photos and quotes to an underlying thesaurus containing certain topics, persons, aesthetic concepts, technologies, archives, genres, persons or companies. A comparison function allows side-by-side inspection of different prints of the same film.

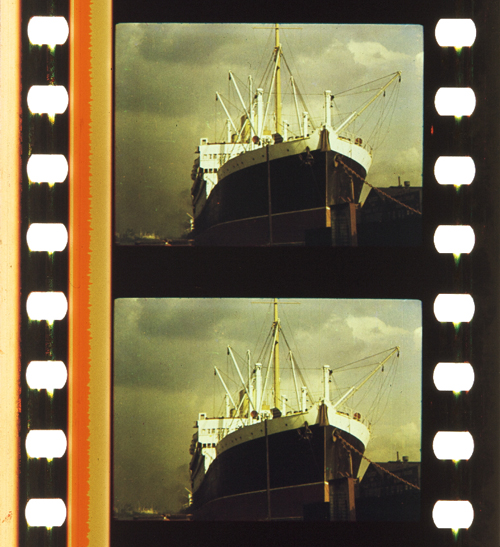

Why film color?

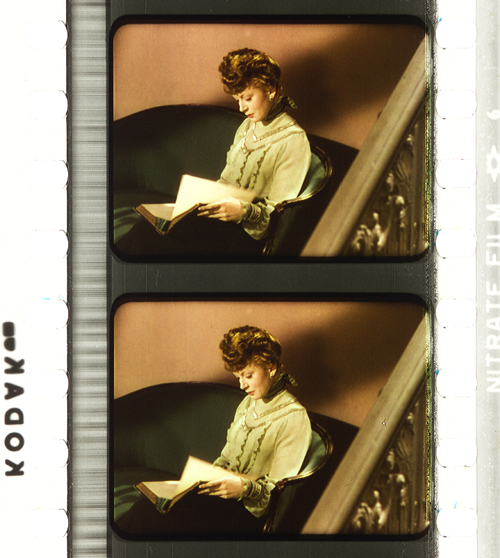

High-resolution photographs displayed in galleries are a central part of the Timeline of Historical Film Colors. Early on I developed a method to photographically capture and document historical film materials in a standardized way. It uses a modular and calibrated camera set-up based on a DSLR camera with a macro lens and remote control from the computer to adjust all the parameters. It is crucial to show the full range of color processes in an aesthetically pleasing way, one that aims at recreating the visual impression on the bench, including the edge information and color distribution in the perforation area. These elements are vital for the identification of film stocks and the genealogy of prints.

These photos allow researchers and students to examine individual historical prints, since they often have to work with less-than-ideal digitizations on DVDs and Blu-rays that are just a faint echo of the historical source material. In recent years this photographic method has been adopted by my teams in the current research projects. Some archives, such as the Academy Film Archive, have started to use the method, and the BFI National Archive and the George Eastman Museum plan to do so soon.

During the last years my teams and I visited many archives in Europe, the US and Japan to take these photographs, such as the Harvard Film Archive, EYE Filmmuseum Amsterdam, National Film Archive Prague, Deutsche Kinemathek Berlin, the Academy Film Archive, the Library of Congress, George Eastman Museum, the BFI National Archive, Cinémathèque française Paris, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv Berlin, Museum of Modern Art, DFF Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum Frankfurt, the National Film Archive of Japan and others.

On the Timeline of Historical Film Colors each contributing archive is represented with a header slide that gives access to the film elements from their collection.

The lost colors of film history

Most films produced before the mid-1930s have been passed on in black-and-white prints. It was not until the famous FIAF conference in Brighton 1978 that the colors of the first decades of film history began to attract some attention from insider circles focusing on silent film.

To this day, the lack of awareness of film’s colorful past has persisted. Early applied colors such as tinting, toning, hand-coloring, and stencil-coloring are ephemeral by nature, since each exhibition print was dyed separately, in a variety of shades and hues. Moreover, these prints were produced with highly flammable nitrate cellulose as a base. Many deadly cinema fires in the early decades of the 20th century demonstrated the dangers of nitrate stock. Therefore, many original colored film prints have been hidden in cans sitting on the shelves in archives’ nitrate vaults. These facilities are fitted with special safety measures such as break-off walls and earth dams.

Eventually in the 1950s safety celluloid film stocks replaced nitrate. From that point on, new prints of colored early films were made on safety stock from the black-and-white camera negatives, intermediate negatives, or positive distribution prints. When colored distribution prints were used, the new copies were usually made only in black-and-white.

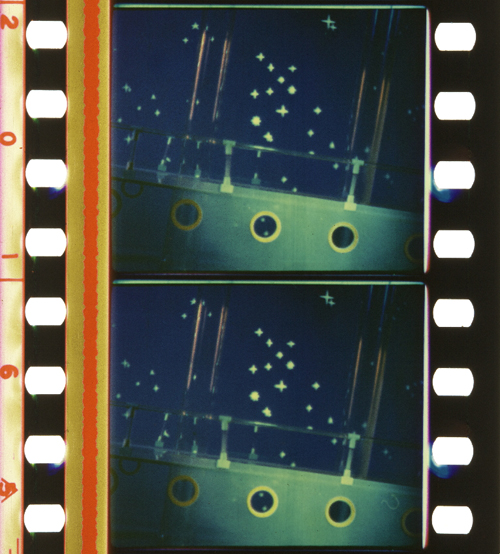

In the early 1980s a second threat to the history of colors in film became apparent. Martin Scorsese was among the prominent filmmakers and scholars who rang the alarm bell over the fading of so-called chromogenic stocks produced from the late 1930s to the 1980s. Due to the physical decay of mainly the cyan dye in these film stocks, original prints become nearly monochromatic, retaining mainly colors in the magenta to red spectrum. To this day, dye fading has remained one of the most pervasive problems for the search of authentic film colors.

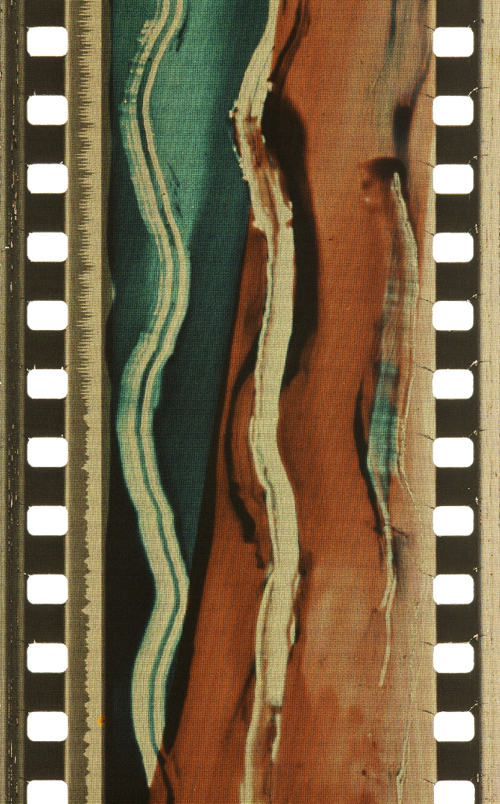

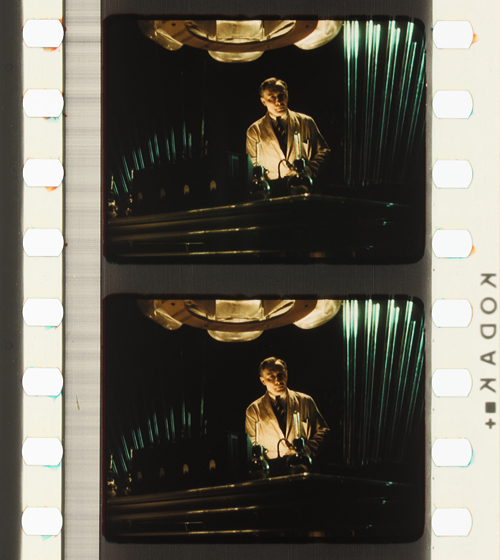

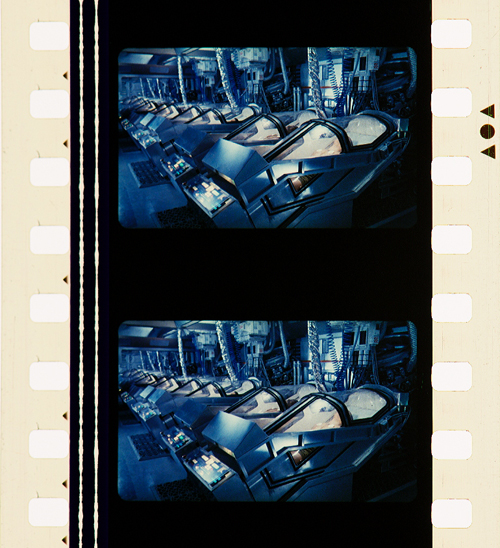

Color fading. Blade Runner (USA 1982, Ridley Scott). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the Eastman Color Print Film by Joëlle Kost.

Applied colors

During the first three decades, so-called applied colors dominated. Historians estimate that about 80% of film prints were colored by tinting, toning, or hand- and stencil-coloring.

Tinting means submerging black-and-white film positives into dye baths, so that the prints’ gelatin emulsion acquired a more or less uniform, mostly monochrome color. Tinting can be identified by the inspection of the perforation area that is also uniformly colored. Toning, on the other hand, is a complementary process whereby the silver image is replaced by colored metallic pigments (metallic toning) or dyes (mordant or dye toning). In contrast to tinting, toning leaves the perforation area mostly colorless.

Tinting. Malombra (ITA 1917, Carmine Gallone). Credit: Cineteca di Bologna. Photograph of the tinted and toned nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Toning. Voyage autour d’une étoile (France 1906, Gaston Velle). Credit: Cineteca di Bologna. Photograph of the toned nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

For these coloring processes the individual prints had to be cut into segments that were then dyed in batches and reassembled into the final distribution print. As a result, individual prints can vary considerably in their color schemes.

Comparison of four differently tinted and toned distribution prints of Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (Germany 1919, Robert Wiene). Copyright: Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation. Photographs by Barbara Flueckiger.

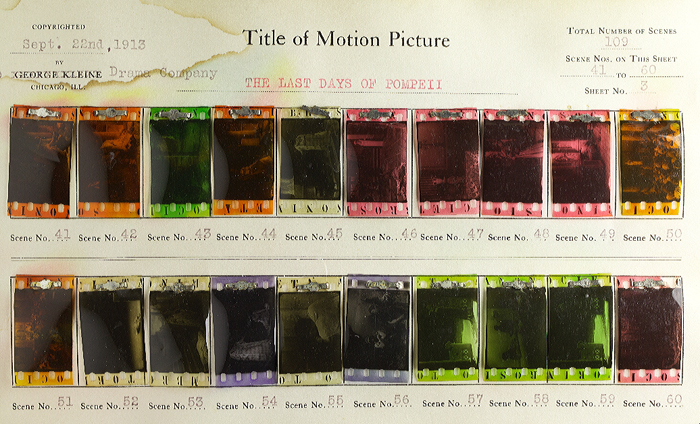

Whether tinting and toning schemes vary due to cultural norms and tastes has remained a topic of debate. To a high degree it is also uncertain who made the decisions about the coloring, except for cases where scripts, production notes, or film negatives indicate the attribution of colors. In addition to colored prints there were so-called copyright books that show the color scheme by single frames attached to the pages of the booklets, deposited at the Library of Congress by distributor George Kleine. Subtle shades emerged that often make it difficult to distinguish between the two, because the black silver image gives way to nuanced interactions with the tinting dyes in middle tones.

Copyright book from George Kleine: Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (Italy 1913, Eleuterio Rodolfi). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph Barbara Flueckiger.

In some cases, combining tinting and toning allowed for two colors to appear within a single image.

Tinting and toning combined. Sumurun (Germany 1920, Ernst Lubitsch). Credit: Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. Photograph of the tinted and toned nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

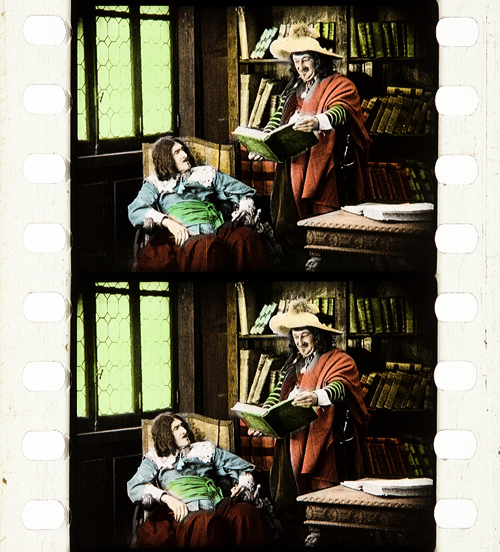

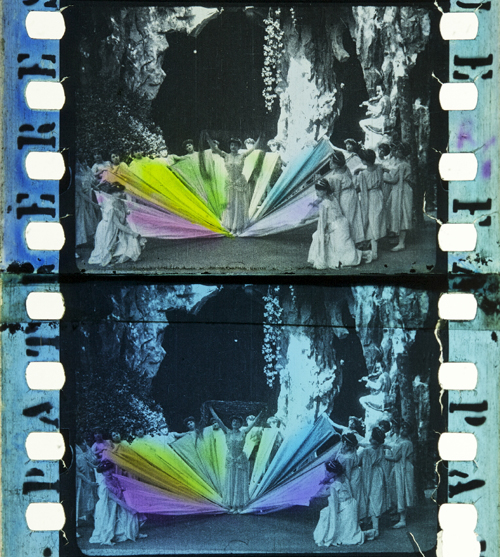

The range and variety are even greater in the case of hand and stencil coloring. These techniques generally required the application of up to six dyes on each individual frame, either by hand through tiny brushes or by cut-out stencils. These laborious processes were demanding, given the small image area and the huge number of frames, generally 16 to 18 per second of running time. Hand-colored films show an uneven application of dyes with soft transitions between individual colors. For stencil coloring, each dye necessitated a separate, colorless print from which the stencils were cut out by needles or metallic styluses. As a result, shapes appear more or less sharp-edged. It was a mechanized version of hand coloring that allowed the coloring of feature-length films and higher numbers of distribution prints. Over the years, improved techniques were introduced to transfer the shapes from projected magnifications onto the film prints with the help of pantographs.

Hand coloring: Métamorphoses du papillon (France 1904, Gaston Velle). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the hand-colored nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Stencil coloring. Cyrano de Bergerac (Italy/France 1923, Augusto Genina). Credit: EYE Filmmuseum Amsterdam. Photograph of the tinted, toned and stencil colored nitrate film by Barbara Flueckiger.

Needless to say, stencil and hand coloring were reserved for more ambitious or luxurious films. However, they also allowed for the creation of a higher reality effect in documentaries, travelogues, or fashion films by anticipating the development of mimetic colors. Exotic places, ethnicities, or historical settings were among the prevailing topics of stencil-colored films.

Documentary. La mangouste ou rat des pharaons (France 1914). Credit: Cineteca di Bologna. Photograph of the stencil-colored nitrate print by Noemi Daugaard.

Fashion film. Modeflitsen (France 1918). Credit: EYE Filmmuseum Amsterdam. Photograph of the stencil-colored nitrate print by Bregt Lameris.

Travelogue. Coiffures et types de Hollande (France 1910, Alfred Machin). Credit: Cineteca di Bologna. Photograph of the stencil-colored nitrate film by Barbara Flueckiger.

In fact, the richness and scope of stencil-colored films can be fascinating to the modern viewer. That holds true for both the bolder color in the first decade of the 20th century or the more nuanced pastel shades that became increasingly prevalent in the 1920s.

Bold colors in early film. L’Amour d’esclave (France 1907, Albert Capellani). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the stencil colored nitrate film by Barbara Flueckiger.

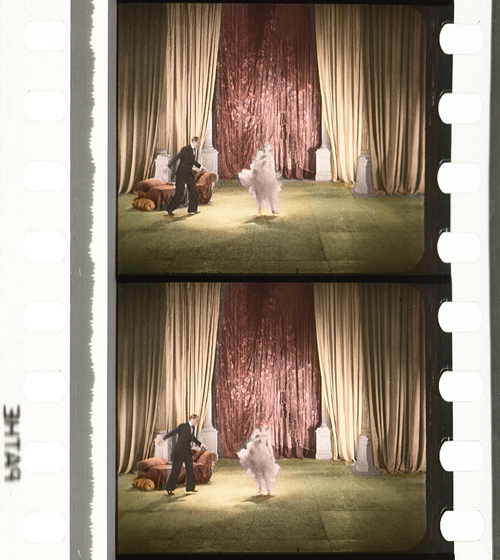

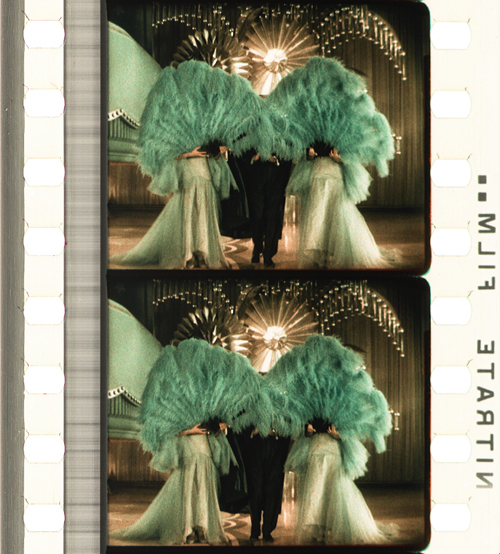

Subtle pastel shades in the 1930s. Elstree Calling (Great Britain 1930, André Charlot; Jack Hubert; Paul Murray; Alfred Hitchcock ). Credit: BFI National Archive. Photograph of the stencil colored nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

A special case of applied colors is the Handschiegl process, a printing process developed by Max Handschiegl and Alvin Wyckoff, often used in Cecil B. DeMille’s films, especially for title cards. It produces highly detailed and precise colors with stunning effects.

Handschiegl. Joan the Woman (USA 1916, Cecil B. DeMille). Credit: George Eastman Museum. Photograph of the tinted, toned and Handschiegl nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

Mimetic colors

Already in France in the 1860s, Charles Cros and Louis Ducos du Hauron separately wrote descriptions of many of the principles for achieving mimetic colors in still photography. As it turned out, however, it was a much more demanding task to develop solutions for moving pictures. Some of the problems related to the high throughput during projection of 16 or more single frames per second. Other problems resulted from much higher requirements for image size on the big cinema screen, where resolution and registration were paramount. Due to the rapid succession of frames necessary for the illusion of movement, minute deviations occurring between frames created disturbing amounts of flicker or color fringing. Contemporary commentators often labeled the result as “color bombardment” that caused “eye strain”.

To this day, mimetic colors combine two to four color components either in additive or subtractive admixtures. In the 19th century their development followed psychophysical insights into the human visual system by Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz. They showed that color impressions are the result of physiological sensors in the human retina sensitive to three different spectral ranges of the visible light.

Additive colors

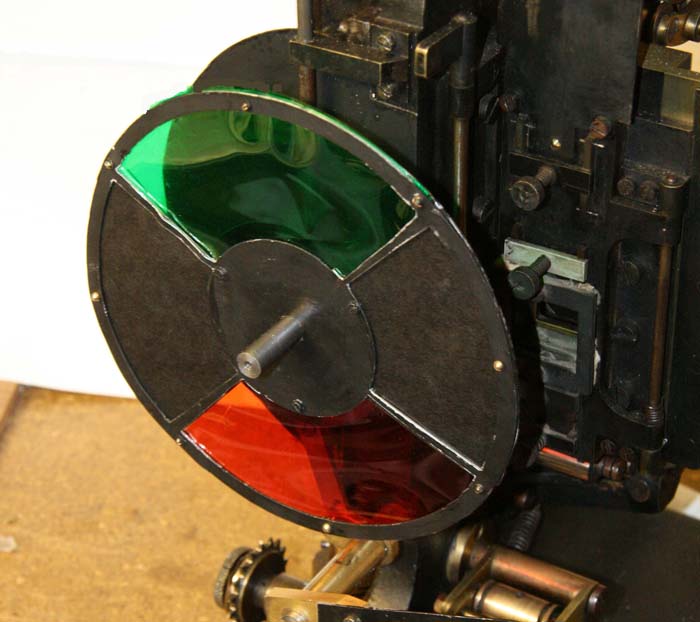

Additive admixtures operate with colored light where the sum of the three additive primaries red, green and blue results in white light. The earliest attempts to create colors on the screen by optical means employed additive principles by rotary filters in front of the camera and projector respectively. These included the three-color Turner Lee and the most successful additive two-color process Kinemacolor.

Rotary filter in front of the Kinemacolor projector used for David Cleveland’s and Brian Pritchard’s reconstruction. Credit: Brian Pritchard.

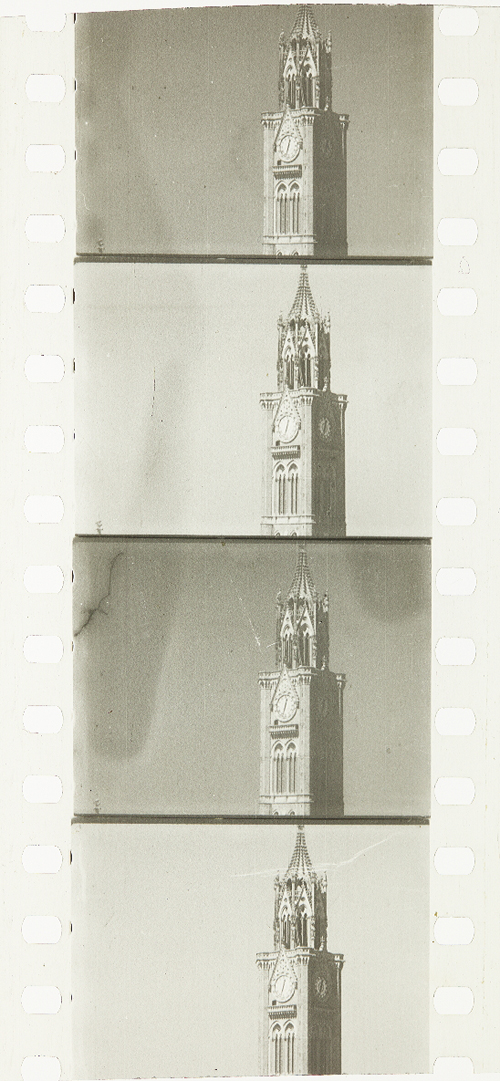

Kinemacolor positive from the Kodak Film Samples Collection. Credit: National Science and Media Museum Bradford. Photograph by Barbara Flueckiger in collaboration with Noemi Daugaard.

In Kinemacolor, rotary filters in red and green spinning in front of camera and projector recorded and transmitted the color information by temporal synthesis. The impression of color was created in the eyes of the spectators. Based on contemporary reports and digital reconstructions, the poor quality and limited color spectrum were readily apparent. Due to the temporal shift between the two successive frames with the red and green color separations, Kinemacolor and all processes operating by the same principle created color fringes and a headache-inducing amount of flicker.

Mroz Farbenfilm. Urlaubfarbenfilm F. Apfelthaler (AUT 1932, Friedrich Apfelthaler). Credit: Österreichisches Filmmuseum. Video and reconstruction by Giorgio Trumpy, David Pfluger and Martin Weiss.

Attempts with temporal synthesis were followed by additive processes that employed spatial synthesis by the application of beam splitters. In this configuration, up to three color records were taken through filters simultaneously to eliminate temporal parallax. But this approach introduced spatial parallax instead, and this arrangement could also create color fringes by poor registration. Gaumont’s Chronochrome process was certainly the most convincing attempt to combine three color separations with this principle.

Gaumont Chronochrome positive from the Kodak Film Samples Collection. Credit: National Science and Media Museum Bradford. Photograph by Barbara Flueckiger in collaboration with Noemi Daugaard.

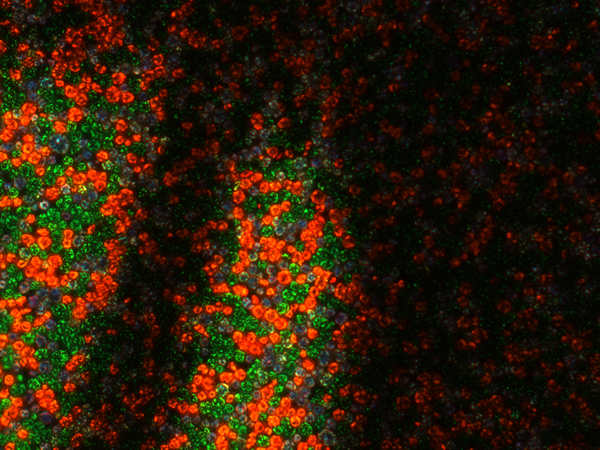

A third type operating with additive admixtures of light are the so-called screen processes. Additive colors are mixed, either by random, small-scale mosaic image elements or by organization into lines. Color impressions in these systems result from the fusion of the individual dots or lines into red, green and blue in visual perception. The effect resembles that of pointillist paintings where colors are divided into small dots.

Lenticular screen processes, by contrast, combine tiny lenses imprinted onto a black-and-white film strip with colored filters in front of the camera and projector.

Mosaic screens created by colored potato starch were popular in still photography with the Lumière brothers’ Autochromes, introduced in 1907 and widely used by professionals and advanced amateurs. The principle was later adopted in the Cinécolor process for color film but failed due to the uneven distribution of the starch particles. Among the line screen processes, Dufaycolor was the most successful one, widely used in documentaries and famously in Len Lye’s experimental films with direct animation painted directly onto the film strip and then captured and distributed on Dufaycolor film stock. Apparently, Lye was not convinced by the somewhat muted color palettes of the process.

Stereoscopic Autochrome Lumière. Exhibition Color Mania – Materiality of Color in Photography and Film, Fotomuseum Winterthur, September 7 to November 24, 2019. Photo by Barbara Flueckiger.

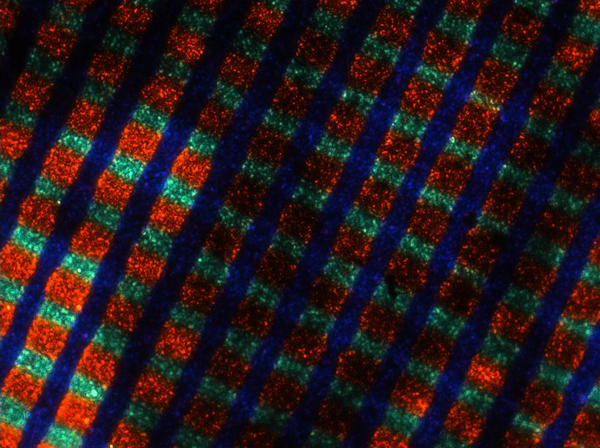

Photomicrograph of Spicer-Dufay, early Dufaycolor (20x). Credit: Photomicrograph by Silvana Konermann.

Dufaycolor. A Colour Box (Great Britain 1935, Len Lye). Credit: BFI. Photograph of the Dufaycolor di-acetate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Lenticular films such as Kodacolor were also mostly used for home movies with the exception of Thomson color for Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête (France, 1949).

None of the additive principles proved to be successful for the long term. Many of them required special installations in the cinema, and most delivered poor results, most notably dim images.

Subtractive colors

Finally, subtractive admixtures became the norm. The three primaries cyan, yellow and magenta filtered the light, with black being the sum of these three subtractive colors. Two or three differently colored emulsion layers are attached to the film base, on one side or both sides of the film.

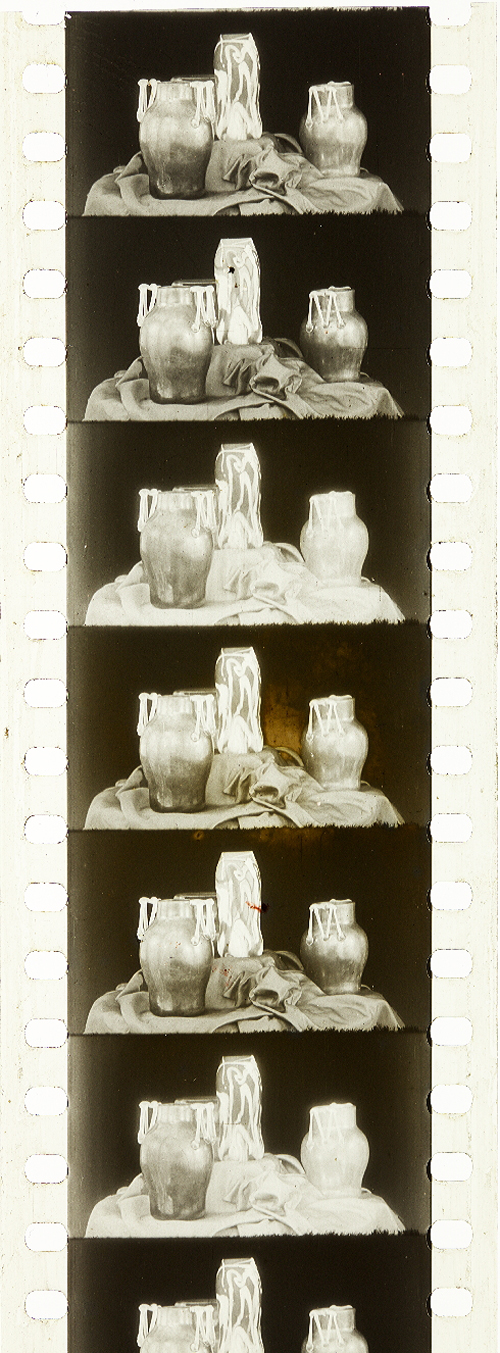

Most early two-color films were using double coated film stock. The earliest one was Kodachrome Two-color developed in 1915, presented in 1916 with the short film Concerning $1000, but mostly in use in the 1920s for fashion films, for the dance film The Flute of Krishna (USA 1926) by choreographer Martha Graham and for the experimental film [Kaleidoscope] by Loyd A. Jones. Kodachrome Two-color film was shot through a beam splitter and combined two emulsions in orange-red and bluish green on either side of the film carrier, with beige, brown and golden tones in the spectrum between the two color components.

Kodachrome Two-color Test Shoot No. III (USA 1922, Anonymous). Credit: George Eastman Museum. Photograph of the Kodachrome two-color double coated stock by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

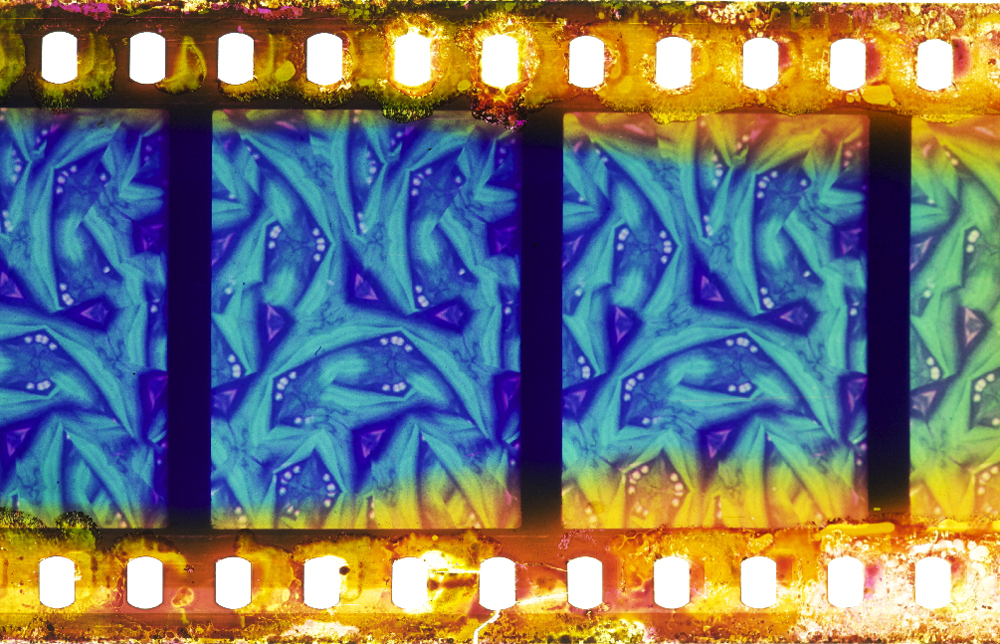

Kodachrome Two-color. [Kaleidoscope] (USA ca. 1927, Loyd A. Jones). Credit: George Eastman Museum. Photograph of the Kodachrome two-color double coated stock by Barbara Flueckiger.

Sirius Farbenfilm. [Farbfilmversuche] (Germany 1920s or 1930, Ludwig Horst; Hans Horst). Credit: Deutsches Filminstitut DFF. Photograph of the Sirius color nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Prizma II. The Glorious Adventure (Great Britain 1922, J. Stuart Blackton). Credit: BFI National Archive. Photograph of the tinted and Prizma II nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

In the 1930s subtractive processes turned to three colors, most famously with Technicolor No. IV and the subsequent Technicolor No. V, which was printed from chromogenic camera negatives. Founded in 1915, the Technicolor Company went through many failures and set-backs, with the exception of a short color rush in the late 1920s with the two-color dye-transfer process Technicolor No. III. Following the series Great Events with 12 short films produced by the Technicolor company to establish the process, mostly musicals and a few other genres exploited the two-color process during this short boom. But some of them are highly remarkable, with sophisticated camerawork by Technicolor’s own cinematographer Ray Rennahan, including the musical Whoopee! (USA 1930, Thornton Freeland) choreographed by Busby Berkeley, King of Jazz (USA 1930, John Murray Anderson, Pál Fejös), Doctor X (USA 1932, Michael Curtiz), and Mystery of the Wax Museum (USA 1933, Michael Curtiz).

Technicolor No. III. Doctor X (USA 1932, Michael Curtiz). Credit: UCLA Film & Television Archive. Photograph of the Technicolor No. III dye-tranfer nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Technicolor No. III. King of Jazz (USA 1930, John Murray Anderson; Pál Fejös). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the Technicolor No. III dye-tranfer nitrate print by Olivia Kristina Stutz.

While the technologies applied in Technicolor’s various processes changed considerably over the years, the beam splitter was one of the few constants. Both in Technicolor No. II and III, a beam splitter separated the two color records and captured them mirrored upside down on one black-and-white negative. The bulky and heavy Technicolor No. IV camera recorded the color separations on three black-and-white 35 mm negatives. From these three negatives matrices were produced as wash-off reliefs, ready for the dye-transfer of the three primaries onto the positive print. The result was a series of color images, along with the frame lines and the soundtrack as silver images.

For almost two decades Technicolor dominated the market for high-quality color films. Part of its success was due to a comprehensive package that included the camera, specialized cinematographers, and all the lab works executed exclusively in Technicolor’s own plants. One of the building blocks of Technicolor’s long-term dominance, however, was the so-called Color Advisory Service, famously led by color consultant Natalie M. Kalmus. She defined aesthetic guidelines for film productions shot with the process, informed by color norms related to concepts of “elevated taste,” located in a broader cultural context with references to the concept of “color consciousness.”

Technicolor No. IV. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (Great Britain 1943, Michael Powell; Emeric Pressburger). Credit: BFI. Photograph of the dye-transfer nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Technicolor No. IV. Blood and Sand (USA 1941, Rouben Mamoulian). Credit: BFI. Photograph of the dye-transfer nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

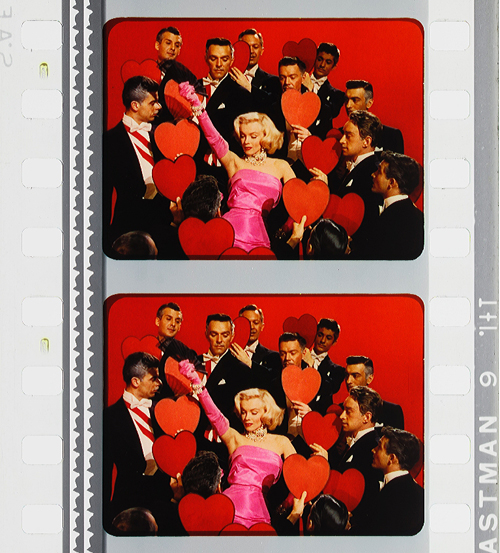

Technicolor No. IV. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (USA 1953, Howard Hawks). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the dye-transfer safety print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Despite all the efforts to control the color schemes, people often associate Technicolor with highly saturated, deep colors. On close inspection in our detailed analyses of color films, however, we have observed that many films adhere to the rules with mostly restrained color schemes and unsaturated backgrounds to guarantee optimal figure/ground separation. But there are also deviations from these self-imposed norms, surprisingly clashing hues even in films produced with Natalie M. Kalmus as color consultant.

Moreover, there is a great variability of different looks and color applications during the almost two decades. Individual color aesthetics were related to personal styles of cinematographers, directors or production companies, genres or changing preferences in fashion and design, and changing color compounds and recipes employed in the process. Technicolor’s idiosyncrasies – what we perceive as typical “Technicolor look” – are mostly due to the dye-transfer process itself. Pasty, dense colors in patchy structures create an almost opaque appearance on the screen, an effect somewhat like oil paint. When we work with the film elements on the bench in archives, we not only have to increase exposure considerably due to the density of the film stock, but we also notice the color layer’s almost sticky viscosity, often visible as a relief on the surface.

Compared to Technicolor, Gasparcolor produced much more saturated, brilliant and luminous colors. In fact, the process, developed in the early 1930s by Hungarian emigré Béla Gaspar in Germany, was possibly the most advanced and complex process at the time. In its principle–the silver dye-bleach process described by Raphaël E. Liesegang in the late 1890s – the silver acted as a catalyst for the local destruction of the dyes embedded in the three emulsion layers on the two sides of a reversal positive. It is thus a chromolytic reversal process. Due to the political circumstances during the Third Reich in Germany, Gaspar eventually had to flee.

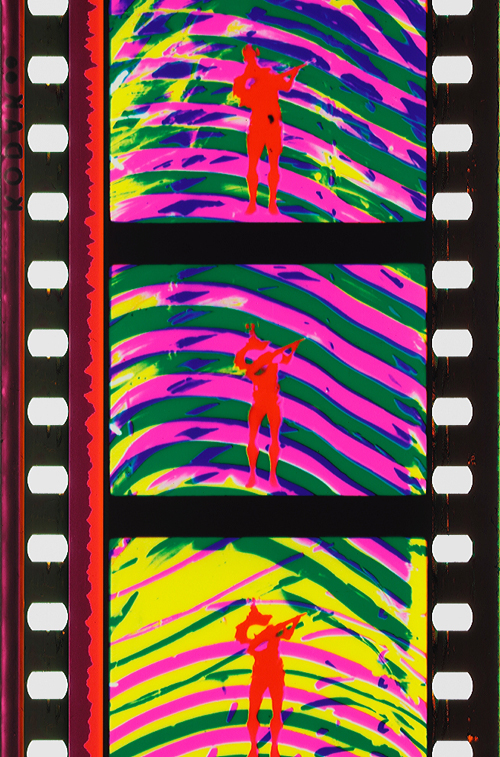

Like Technicolor Gasparcolor required the recording of three color separations on black-and-white negatives. Since most of the Gasparcolor films were animations, these separations were captured in succession on adjacent film frames but could of course also have been shot through a beam splitter similar to Technicolor No. IV. In fact, only one documentary is widely known, Colour on the Thames (Great Britain, 1936), shot by Adrian Cornwell-Clyne. Among the films produced with Gasparcolor are famous avant-garde experimental films by Oskar Fischinger, Hans Fischinger, and Len Lye. Gasparcolor prints can easily be identified by the black perforation area and the colored soundtrack.

Gasparcolor. The Ship of the Ether (Netherlands 1934, George Pal). Credit: BFI National Archive. Photograph of the Gasparcolor nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Gasparcolor. Colour on the Thames (Great Britain 1935, Adrian Klein). Credit: BFI National Film Archive. Photograph of the Gaspar color nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Gasparcolor. Rainbow Dance (Great Britain 1936, Len Lye). Credit: Museum of Modern Art. Photograph of the Gaspar color nitrate print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Both Technicolor and Gasparcolor prints stored in archives are in remarkably good shape, due to their stable colors. Ironically, chromogenic film stocks, the technical principle that ultimately won the competition and became the new standard, had the least stable dyes. Chromogenic means that the dyes need to be developed after exposure. Embedded in the emulsion of a single strip of film stock are three or more layers. These layers are sensitive to different spectra. All contain silver halides and the color-forming substances, so-called dye couplers that are subsequently developed into dyes. In a second stage the silver is bleached out and leaves the color information in the form of finely dispersed dye clouds in the three or more emulsion layers in cyan, magenta and yellow. The result is a highly translucent, glowing image whose fine-grain structure depends on the speed of the film stock. The slower the speed, the finer the grain.

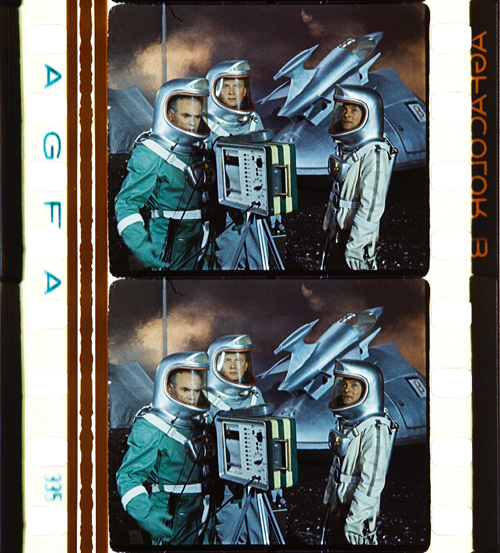

In contrast to Technicolor the shooting of the chromogenic film could be done with normal cameras on one negative or camera reversal. Chromogenic films increasingly became the norm, starting with Agfa’s first negative-positive process Agfacolor. Emerging in the late 1930s, Agfacolor was promoted by German propaganda in a bid to counteract Technicolor’s dominance. Agfacolor had particularly soft colors in the pastel range with a typical, slightly darkened orange-tomato red. Difficulties in the blue range produced turquoise shades that become quite apparent in skies. Greens had a tendency to look brownish or blackened; shadows had a greenish tinge. Chromogenic multilayer film stocks were incredibly difficult to balance and to produce, requiring a high level of knowledge in physics and chemistry.

Agfacolor. Münchhausen (Germany 1943, Josef von Báky). Credit: Copyright Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation. Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv. Photograph of the Agfacolor safety print (acetate) by Barbara Flueckiger.

Agfacolor. Opfergang (Germany 1944, Veit Harlan). Credit: Copyright Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation. Filmmuseum Düsseldorf. Photograph of the Agfacolor Safety Print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Agfacolor. Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (Germany 1944, Helmut Käutner). Credit: Copyright Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation. Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv. Photograph of the Agfacolor nitrate print by Michelle Beutler.

Agfacolor. Der schweigende Stern (German Democratic Republic 1960, Kurt Maetzig). Credit: Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv. Photograph of the Agfacolor safety print by Josephine Diecke.

After World War II ended, the Allies were able to exploit German color-film patents. The result was the appearance of Fujicolor, Eastman Color, and many derivatives, such as Ferraniacolor, Ansco Color, and Sovcolor. The worldwide adoption of color in film production soon followed.

Sovcolor. Ivan the Terrible, Part II (Russia 1958, Sergei M. Eisenstein). Credit: Museum of Modern Art. Photograph of the Sovcolor safety print by Barbara Flueckiger. (The film was shot in the 1940s on captured Agfacolor stock, but the delay in the release of the film until 1958 meant that distribution prints were on Sovcolor stock.)

Fujicolor. Matador (Spain 1986, Pedro Almodóvar). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the Fujicolor safety print by Barbara Flueckiger.

Eastman Color. Aliens (USA/Great Britain 1986, James Cameron). Credit: Academy Film Archive. Photograph of the Eastman Color Print Film Type 5384 by Joëlle Kost.

Eastman Color. Gattaca (USA 1997, Andrew Niccol). Credit: Library of Congress. Photograph of the Eastman EXR Color Print Film Type 5386 reference print by Barbara Flueckiger.

A plurality of styles emerged, less defined by technical limitations than by cultural contexts and individual preferences of filmmakers, art directors, costume designers, and cinematographers. Color aesthetics in film are not only created by hues, color schemes, and color contrasts, but also by lighting styles, by material properties of surfaces and textures, by depth of field, image composition, and by movement. The combination of these factors influences the image’s figure-ground relationships.

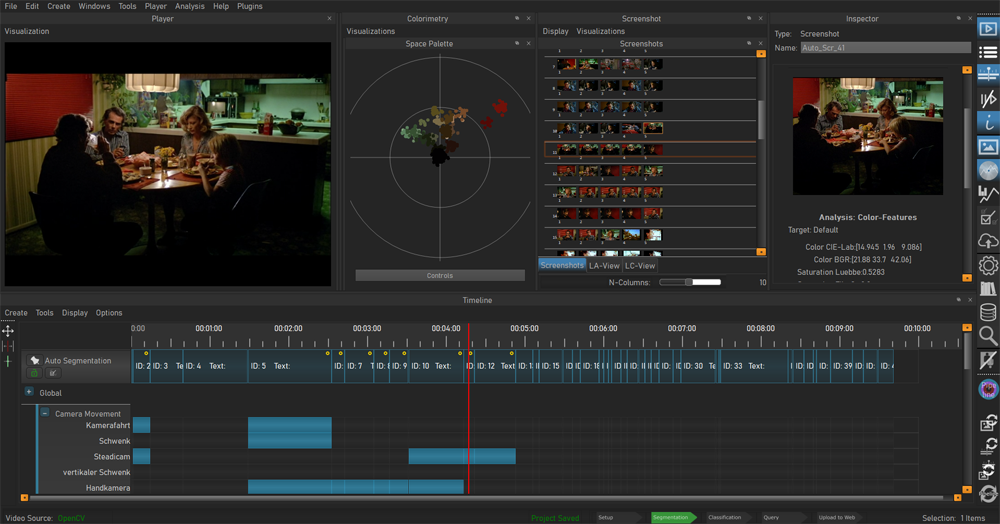

In the course of our research, we investigated a large corpus of more than 400 films – mainly from 1895 to 1995 – with a computer assisted workflow. A video annotation software has been developed based on our approach since 2017, when we figured out that tools available then were not well suited to the detailed annotation and visual analysis of film (color) aesthetics. The visual analysis and annotation software VIAN has been created by Gaudenz Halter in collaboration with the Visualization and MultiMedia Lab of the University of Zurich. The tools enable researchers to create detailed analyses including figure/ground separation and a large range of visualizations that make diachronic developments immediately evident or support the testing of new hypotheses.

A deepened understanding of color film technologies and aesthetics is an essential prerequisite for the scientifically sound digitization and restoration of color films, which is one of the most pressing topics today and therefore remains at the center of our research activities.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my immense gratitude to Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell for publishing this blog post and for all the inspiration that guided my research.

A huge thank you to my teams ERC Advanced Grant FilmColors, SNSF Film Colors. Technology, Cultures, Institutions, ERC Proof-of-Concept VeCoScan.

Special gratitude is dedicated to all the film archives with their wonderful collections.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement No 670446 FilmColors.

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

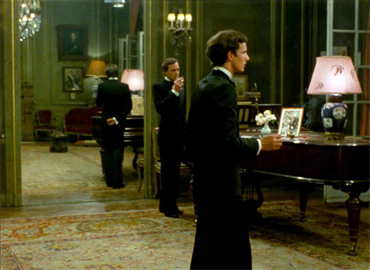

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

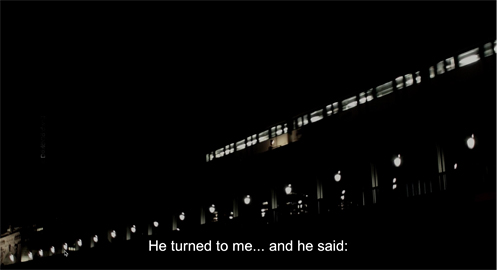

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

Rotterdam surprises

Mitra (2021)

Kristin here:

On Saturday morning (8:30 am our time), the International Film Festival Rotterdam will be screening its annual Surprise Film. We’re naturally curious to learn what it is. But Rotterdam comes so early in the year that often we go into its other offerings knowing almost nothing about them. Here are two of the very pleasant surprises from recent days.

Iranian cinema from the Netherlands

Kaweh Modiri, the director of Mitra, was born in Iran but has lived in the Netherlands since he was six years old. Still, he remains concerned with Iranian issues and clearly has been influenced by the flourishing Iranian art cinema of recent decades.

Asghar Farhadi’s success in international festivals and territories has been the most influential instance recently, at least outside of Iran. His plots are often built around conflicts, not between good and bad people, but behind people who clash because of cross-purposes. Late revelations and tortured discussions lead to reconciliations that are not the happy endings of Hollywood films but instead are resigned agreements to admit mistakes and make compromises.

Mitra is such a film, but it is based around more politically based conflicts than Farhadi has used–ones that have life and death consequences for those involved.

The film moves between two settings and eras: Tehran in 1981-82, the years shortly after the ouster of the Shah, and the Netherlands in 2019, the fortieth anniversary of that revolution. The opening is set in 1982, when the heroine, Haleh, receives an abrupt, unexpected telephone calls announcing that her daughter Mitra has been executed. We move then to 2019, when Haleh, now an academic in the Netherlands, addresses a conference on “The Islamic Revolution at Forty.” Soon she is visited by members of “The Organization,” a group aimed at bringing down the current government of Iran. They tell Haleh that Leyla, whose betrayal of Mitra caused her death, has arrived with her daughter in the Netherlands. She goes under the name Sale, having appealed for refuge status. The Organization wants Haleh’s confirmation that Sale is indeed Leyla.

The rest of the plot centers around a shifting relationship, as Haleh vows revenge on Leyla. Her goal is complicated by the fact that she has never actually seen Leyla, having only heard her voice. Nevertheless, she calls Sale and is convinced that she recognizes the woman’s voice, even after nearly forty years. Once they meet, however, Haleh seemingly bonds with Sale and her endearing daughter Nilu. Indeed, Haleh’s attraction to Nilu hints at her possible acceptance of Sale as a substitute daughter and Nilu as a granddaughter.

Interspersed with this story are flashbacks to the younger Haleh’s 1981 experiences, when Mitra, who has joined the resistance in Iran, is still alive. Scenes like a clandestine meeting with Mitra at a crowded market emphasize Haleh’s love for her daughter (top of section).

Modiri expertly lures us into sympathizing with all the characters involved. To the end we remain uncertain as to whether Sale, who after some doubts accepts Haleh as a friend and even as a substitute mother in a new land, is actually the treacherous Leyla. Even if she is, is it worth ruining young Nilu’s life to turn Sale in to the ruthless Organization?

Supporting all this is Haleh’s relationship with her brother Mohsen, who at first seems a somewhat comic, eccentric sidekick but is later revealed to be suffering the effects of torture and lengthy imprisonment in Iran. His exchanges with Haleh initially seem like sibling bickering, but he becomes the moral compass that holds her together as she pursues revenge (see top).

Mitra starts out seeming to be a conventional revenge story, but its moral and personal shifts and surprises lead to a moving and not-quite-resolved ending.

The film has had its world premiere at the IFFR and is due for a May 20 release in the Netherlands. I hope it plays other festivals and travels further, because it is a definite contribution to the continuation of world interest in Iranian cinema. Like other such Iranian films, it had to be made elsewhere (the scenes set in Iran were shot in Jordan), but it carries forward what we have loved about Iranian films.

An Australian surveillance-cam thriller

Jonathan Ogilvie’s Lone Wolf (2021) adopts the new convention of creating a story based largely on surveillance and cell-phone footage. In a frame story Kylie, a Special Crimes Sergeant, bursts into the office of an unnamed Police Commissioner and demands that he watch a video she has secretly compiled from a mass of such footage.

The inner story is seemingly set more-or-less in the present day, but it’s a slightly alternative world in which surveillance has become even more pervasive than it already is. The read-outs in the images reveal that cameras are spying on the characters from such household devices as TVs and smoke detectors. One of these is, ironically, in a bathroom where Winnie sneaks the occasional cigarette by an open window (above). How Kylie gets access to all of these is never explained, and the premise is implausible–especially in scenes built around extensive, undamaged footage which she has somehow managed to extract from a phone that has been through a bomb explosion.

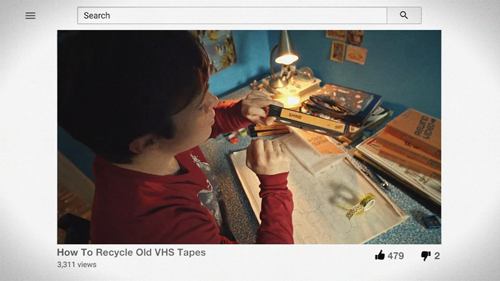

If one stifles such doubts, however, the tale Kylie’s film tells is an absorbing one, full of twists and turns. It centers on Conrad and Winnie, a couple who run a book/video-rental/sex shop and do occasional jobs for underground political groups. They are not the most appealing characters, but they gain our sympathy through their devotion to Winnie’s charming little brother Stevie, who has Down’s Syndrome and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

Australia is soon to host a G20 meeting, and a man from a radical group asks Conrad to set up a “victimless atrocity” in the form of a bomb explosion in a deserted area. At first Conrad refuses, but when offered a large sum, he gives in. Despite the grimness of this plot thread, there is quite a bit of humor in the film, provided by Stevie and by a group of Conrad’s misfit friends who gather to play cards above the shop. The combination of found footage also creates occasionally amusing moments, as when the film-within-a-film includes an instructional YouTube-style video that Stevie has posted or poor-quality footage from an old security camera in the shop that Winnie and Conrad think has been turned off (bottom).

The consequences of the bomb plot introduce a grim twist, but the return to the frame story creates a more gratifying one as Kylie reveals why she has pressed her video upon the Commissioner.

While Rotterdam provided Lone Wolf‘s world premiere, it has a distributor in Australia, though its August, 2020 release was postponed by the pandemic. Ogilvie hopes it will have wide theatrical play after a possible in-person premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival this coming August.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to discover these surprises!

Lone Wolf (2021)

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).