Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Friday | May 14, 2021 open printable version

open printable version

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

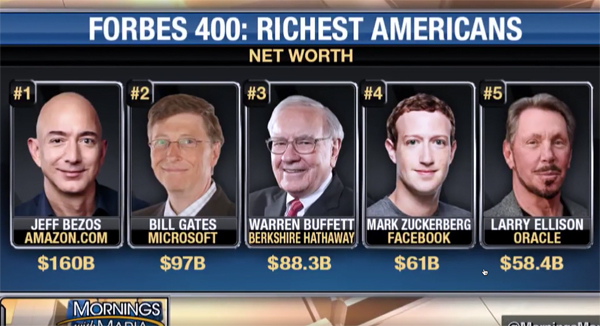

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

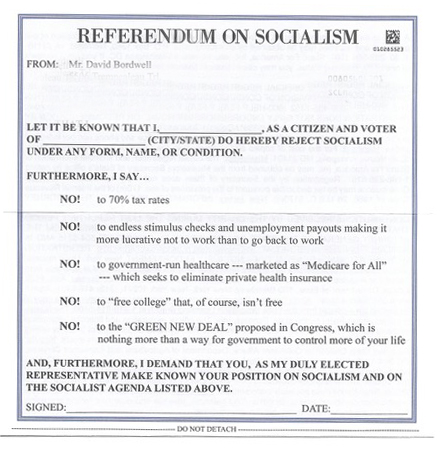

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

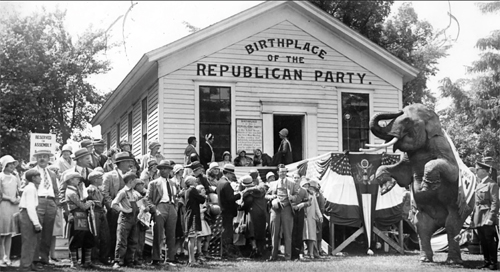

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

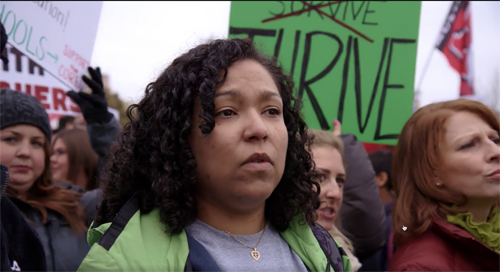

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

The Passionate Thief (1960).

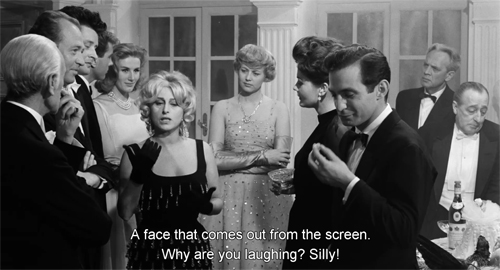

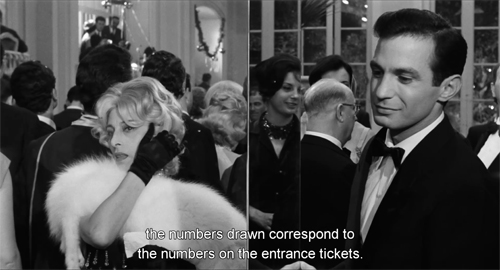

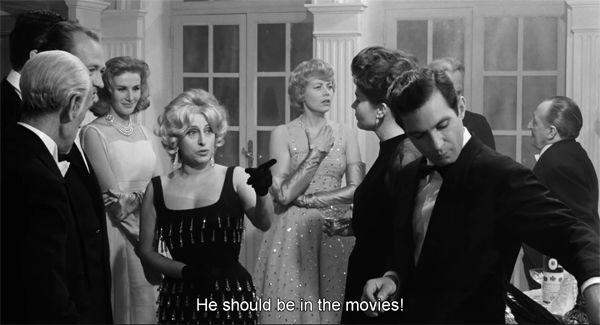

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).