Archive for March 2022

Oscar’s siren song: The revenge

King Richard

The Oscars are upon us again. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may have decided that “Music (Original Score)” is one of the categories not important enough to show live along with the rest of the awarding of the golden statuettes. We, of course, think this is absurd. (Will the Oscar ceremony gain a single extra TV viewer through this tactic?)

We welcome back our friend and colleague Jeff Smith to continue his annual comments and predictions concerning the nominees in both musical categories: song and original score. This year he has, if anything, outdone himself in providing insights into the historical contexts and the formal qualities of the ten nominees.

‘Tis the season to pass out little gold men to people in gowns and tuxedos. This year’s Oscar ceremony is scheduled to take place on Sunday night, March 27th. And this is about the time when I offer my annual assessment of the nominees in the music categories.

The title I’ve given this blog post might appear to represent a failure of imagination. After posting the first of these surveys, I opted for a sequelitis motif by using Roman numerals and corny words like “Return.” Yet this year’s sequel title seems all too apt. The producers of the Academy Awards have been winnowing away the amount of airtime given to the music awards in the past two years. They no longer present all five of the Best Original Song nominees as part of the broadcast. This year the award for Original Score will be prerecorded before the broadcast and the winner announced in between other, presumably more important awards.

If the Academy Awards doesn’t seem to care about these categories, then why should I? Well, because as a scholar and educator, this is what I do. Consider this blog post the petty revenge of someone who believes these categories still matter, even if the organization sponsoring the awards doesn’t seem to think so.

In the case of the award for Best Original Score, there will be some bitter irony in the fact that we’ll never see the faces of the composers on the big five-way split screen used to show nominees. But we’ll hear their scores played as walk-up music if Penelope Cruz wins for Best Actress. Or if Greig Fraser wins for Best Cinematography. Or Encanto wins for Best Animated Film. Or Jane Campion wins for Best Director. Or Adam McKay wins for Best Original Screenplay.

At the end of each award preview, I’ll make an educated guess as to who the winner of the category will be. All the usual caveats apply. These predictions are not intended for wagering purposes, I offer the usual disclosure that my predictions over the years typically yield one right and one wrong. (It’s up to you to figure out which is which.)

Lastly, a warning of some spoilers. I do my best to try to avoid giving away too much information about a film. But sometimes it is unavoidable if you want to get into the nitty gritty of the choices composers make in how they score their films.

The Susan Lucci of songwriting

Last month, Diane Warren earned her 13th Oscar nomination for Best Original Song, the most by a woman in any category without a win. This isn’t the most, though, in the music categories as composers Thomas Newman and Alex North both earned 15 nominations for Best Score without ever taking home Oscar. Last April, Warren told Billboard that she the old saw about it being “nice to be nominated” was true, but that she really would like to finally win an Oscar. Said Warren, “I’m like a sports team that has lost the World Series for decades. This is 33 years since my first nomination.” Warren’s record begs comparison with soap opera star Susan Lucci, who earned 18 Daytime Emmy nominations for her role as Erica Kane on All My Children before finally winning the award in 1999.

Warren’s current nomination is for her song, “Somehow You Do,” which is featured in Rodrigo Garcia’s drama about opioid addiction, Four Good Days. Sung by Reba McEntire, Warren’s number is a countrified version of the sort of power ballad that the tunesmith has specialized in for decades. The first verse is modestly arranged for two guitars, one an acoustic and the other pedal steel. The song gradually adds more texture as it nears the chorus, with the bass adding some bottom end and a chorus punching up McEntire’s lead vocal.

The second verse continues to build with the addition of a drum kit that firmly establishes the song’s 6/8 meter and slow tempo. The song’s bridge introduces a contrasting melody and roughens up the sweetness of McEntire’s voice with some pulsating power chords played by an electric guitar. This prepares for the requisite key change as the song shifts to the final verse and chorus. The tune reaches its emotional peak here and then gradually tapers down. A brief coda returns us to the spare sound of McEntire’s voice accompanied by an acoustic guitar.

The song is very well-crafted if a bit by the numbers. It is a testament to Warren’s mastery of her craft that she finds new ways to enliven the venerable AABA structure of classic songs and fit them to the dramatic needs of the films she works on.

Yet Warren’s chances of winning seem to be hampered by a couple of factors. If you asked yourself, “What is Four Good Days?”, you are not alone. The film garnered little attention from critics and fans, earning less than $900,000 during its theatrical release. Moreover, although McEntire is a huge star in the world of country music, that probably won’t cut much ice for voters in the Academy music branch who represent a different industry demographic.

There seems little doubt that Warren has a dedicated following within the music branch. However, although it is big enough to consistently yield nominations, it isn’t large enough to deliver the big prize. Warren likely will have to content herself with “It’s nice to be nominated.” If she starts to feel too downhearted, Warren can console herself by looking at her royalty statements for “Rhythm of the Night.” Or “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing.” Or “How Do I Live.” (You get the idea…)

The Legends (and I don’t mean John, Chrissy, Luna, and Miles)

The next two nominees are among pop music’s biggest icons, representing more than ninety years of combined experience in the biz. A bit surprisingly, though, both artists also are first-time Oscar nominees.

First up is the man who epitomizes Northern Soul: Irish singer and songwriter Van Morrison. Morrison is nominated for “Down to Joy” from Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast. Like Branagh, Morrison was born and raised in Belfast. He also has been closely associated with the city throughout his career, receiving the monikers of “the Belfast Cowboy” and “the Belfast Lion.” The early peak of Morrison’s career also coincides with the onset in 1969 of “the Troubles” depicted in Belfast. Besides “Down to Joy,” Branagh selected eight other Morrison tracks for the film’s soundtrack, many of them lesser-known tracks like “Caledonia Swing” and “Carrickfergus.” By digging deep into Morrison’s catalog, Branagh is not only able to provide a musical biography of his childhood, but also indicates how deeply Van the Man’s music was woven into the fabric of everyday life in Belfast.

Morrison’s “Down to Joy” also shows the durability of AABA form, albeit in this case channeling the sound of his early mid-tempo rockers like “Caravan” and “Domino.” The latter recordings are among the songs that would cement Morrison’s status as a Celtic interpreter of the revue style of sixties soul music, especially the Stax sound epitomized by singers such as Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. Morrison based his entire career on melding those influences with more native elements of Irish folk music. For nearly sixty years, Morrison has demonstrated that the idiom of sixties soul seems almost timeless, an impression confirmed by even more modern practitioners, like Sharon Jones & the Dap Kings or Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats.

Appearing over the end credits, “Down to Joy” neatly encapsulates the overall tone of Belfast and its mix of nostalgia, melancholy, and hope. At the end of Belfast, young Buddy and his family have been displaced by “the Troubles,” forced to relocate by threats of IRA retaliation. Their journey to England is colored by the pain of family separation. Yet it also represents a horizon of new possibilities. “Down to Joy” reflects that latter sentiment with lyrics describing a new morning after a dark night, and the glory and gratitude expressed through Buddy’s child-like naivete.

So, what are the chances that Van the Man wraps his hands around a small golden dude? Not very good, if you ask me.

Don’t get me wrong! Morrison albums of the late sixties and seventies – Astral Weeks, Moondance, Tupelo Honey, Saint Dominic’s Preview – are stone cold classics. It’s Too Late to Stop Now is among the finest live albums ever recorded. Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” is my wife’s very favorite song ever!

I’m a Van fan, but his public statements about the United Kingdom’s Coronavirus restrictions have probably killed his chances of winning an Oscar. If younger members of the Academy know Morrison at all, it is likely as a conspiracy crank who is now recording with equally obnoxious anti-vaxxer Eric Clapton. I just can’t see Academy voters giving Morrison a platform to air his views on social distancing and lockdowns. If they did, it would produce the kinds of news clips and headlines that the Academy would like to avoid. Just imagine the public response to an acceptance speech in which the boos from the crowd rain down on the winner. I imagine that a lot of folks in the music branch just can’t bring themselves to vote for Morrison in the current political landscape. And, even as a lifelong fan, I can’t really blame them.

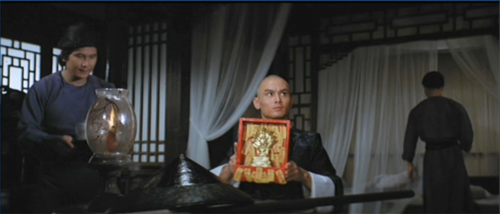

The third nominee for Best Original Song is “Be Alive” by DIXSON and Beyoncé Knowles Carter. The song appears in the end credits of King Richard, the biopic about Richard Williams, the father of tennis phenoms Serena and Venus. The tone of the music and lyrics succeed in doing something the film itself struggles to do, namely give voice to the two women who end up rewriting the record books of professional tennis.

In contrast, King Richard casts Williams the elder as a Svengali figure shepherding his young prodigies into the world of big-time sports. He acts as the girls’ agent, manager, coach, and protector, shielding Serena and Venus from the sorts of predations that characterize an industry with a bad reputation for chewing up and spitting out young talent. The lyrics of “Be Alive” speak to the family’s sense of fierce independence and Williams’ own “bootstrap” mentality. This is evident in couplets like:

Couldn’t wipe this black off if I tried

That’s why I lift my head with pride

Later, Beyoncé sings the praises of sisterhood, a theme that can be heard in some of her biggest hits, such as “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” or “Independent Women Part I,” the latter recorded as a member of Destiny’s Child.

With its steady marching tempo borrowed from the Doors’ “Five to One” and Beyoncé’s soaring vocals, “Be Alive” bespeaks a mood of strength and defiance. Yet, it isn’t as well placed as some of the other songs in the category and, unlike many of Beyoncé’s popular records, it also isn’t the kind of earworm that lights up record charts. “Be Alive” peaked at #40 in Billboard’s Hot 100, likely a disappointment considering how well King Richard has performed in other audience metrics.

Come Sunday, I suspect that Beyoncé will likely go home empty handed. Like Diane Warren, she’ll need to console herself with the mantra “It’s nice to be nominated” and the many other Grammys, ASCAP, Billboard, BET, MTV, and American Music Awards that line her trophy case.

The Young Bloods

The final two nominees had big years in the world of entertainment in 2021. An Oscar would put a capper on a period of creative ferment that’s the envy of most singers and songwriters. Yet, for these two performers, it just seems like another day at the office.

Lin-Manuel Miranda received his second Oscar nomination for “Dos Oruguitas,” one of several songs he wrote for the Disney animated musical Encanto. The song is performed by Columbian singer Sebastián Yatra and appears in a flashback that dramatizes Abuela Alma’s tragic backstory. As a young woman, Alma, her husband Pedro, and their triplets attempt to escape their village after war breaks out. During their journey, they are beset by armed horsemen. The refugees scatter, but Pedro is killed when he halts the charging caballeros, presumably to ask for mercy for himself and his family. A candle Alma is holding protects the rest of the group, and its magical properties transform their future home into the “Casita,” a fantastic space where its denizens are revealed to have supernatural abilities and the house has a mind of its own.

The sequence itself is reminiscent of similar moments from films made by Disney’s friendly rival, Pixar. The montage that encapsulates an entire life in a couple of minutes of screen time recalls the opening of Up (2008) which depicts the long, happy marriage of Carl and Ellie until her illness and untimely death. The song that accompanies a flashback explaining the source of a character’s trauma and grief is also seen in Toy Story 2. Cowgirl Jessie relates how she once was her owner Emily’s favorite doll, but ends up forgotten and left behind when Emily grows up. This is all set to the strains of Sarah McLachlan’s “When She Loved Me.” The montage from Encanto nicely fuses together both these narrative devices but gives them a Latin pop spin.

Like “Somehow You Do,” “Dos Oruguitas” begins quietly with a brief introduction played on an acoustic guitar. The slight syncopation of the guitar figure, though, gives it a bit of Hispanic flair. As Yatra’s voice enters, the song’s chord structure follows a chromatically descending bass line, a device that heightens the harmonic tension until it circles back to the tonic. The tune pauses briefly as Abuela confesses her guilt for forgetting what the purpose of the magic was for. Mirabel reassures her that the Madrigal family’s entire livelihood is due to the earlier sacrifices the Abuela made and the suffering she endured. When they embrace, “Dos Oruguitas” kicks back in with a slightly faster tempo and with fuller orchestration that includes strings, percussion, a chorus, and a harp. With the rift between Alma and Mirabel healed, the Madrigals band together to rebuild the “Casita.” The harmony created by the restored family bonds allows it to regain its sentient properties.

As an Oscar nominee, “Dos Oruguitas” has a lot going for it. It accompanies a very emotional scene of intergenerational reconciliation. It is a featured track on the Encanto soundtrack, which has spent the past nine weeks atop Billboard’s Top 200 album chart. And Lin-Manuel Miranda is on a roll having served as the director of Tick, Tick…Boom!, the musical biopic of Rent composer Jonathan Larson, and as the producer of In the Heights, the screen adaptation of Miranda’s own hit Broadway play.

Perhaps the only thing working against it is the fact that it’s been overshadowed by another song from Encanto. “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” is a certified pop culture sensation, spending five weeks as the #1 song on Billboard’s Hot 100, accumulating more than 300 million views on Vevo, and featured in 21 different languages on Instagram. Did Disney submit the wrong song for nomination? Maybe, but “Dos Oruguitas” still might been benefit from the reflected glory of its more popular sibling. This and the fact that Encanto is up for some other major awards have kept Miranda among the frontrunners.

The last nominee is the title song from the most recent entry in the venerable James Bond series, No Time to Die. The tune is performed by Billie Eilish and written by Eilish and her frequent songwriting partner, brother Finneas. Like Miranda, 2021 has been a good year for Eilish. Her new album Happier Than Ever topped the charts in 26 countries across the globe, including the US. It also earned two Grammy awards and landed on several year-end “best of” lists. In addition to her music, Eilish also appeared in two films: a concert film featuring songs from Happier Than Ever and a “behind the scenes” documentary distributed by Neon and Apple TV+ called Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry.

In some respects, Eilish seems like an exemplary contributor to the amazing catalog of songs written for the Bond canon. She is an immensely popular artist. She is also someone who could update the template for the series by adding emo, dream-pop, and electro-pop touches to the usual Bond formula.

In other respects, though, Eilish represents something of a departure from previous Bond songstresses. When one thinks of iconic Bond songs, one thinks of tunes like “Goldfinger,” “Diamonds Are Forever,” “Licence to Kill,” “Goldeneye,” “The World is Not Enough,” “Skyfall,” and “Another Way to Die.” What do these songs all have in common? They are all sung by women with big voices, belters like Gladys Knight, Tina Turner, Adele, Alicia Keys, and the two Shirleys: Bassey and Manson. In contrast, Eilish is known for a much softer style of singing: hushed, sensitive, and intimate. That seems fitting for a performer whose best-known album was inspired by lucid dreaming and night terrors. Yet it seems less well-suited for an almost mythic film character defined by his swagger, toughness, and even a streak of cruelty.

Yet, if there was moment to rethink the traits of the typical Bond song, this was certainly it. In retrospect, the selection of Eilish was a masterstroke by the Bond brain trust led by Barbara Broccoli, the current head of Eon Productions. As the last film to feature Daniel Craig as James Bond, No Time to Die not only caps off his five-film arc, but also serves as a reflexive meditation on the series as a whole. At one level, the explicit meaning of No Time to Die is both simple and banal: everyone dies. Yet, by making references to several earlier films in the series, the accumulated weight of intertextual resonances invests the many deaths that occur in No Time to Die with an unusual sense of depth and gravity.

No Time to Die begins with a scene where Bond visits the tomb of Vesper Lynd, the fellow agent featured in Casino Royale who helps Bond defeat the evil Le Chiffre. Lynd and Bond fall in love, but she proves to be a double agent working for a rival operative. At film’s end, Lynd sacrifices herself when she drowns in a locked elevator car that has submerged.

M then reveals that she was an unwilling accomplice, a victim of blackmail after her previous boyfriend was abducted and threatened.

Bond’s pilgrimage to Lynd’s grave presages several additional deaths in the film. Bond’s best friend, CIA Agent Felix Leiter, and his mortal enemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, are killed in separate incidents. Even Bond himself perishes in the climax of No Time to Die. He sacrifices himself to foil a scheme by Lyutsifer Safin to unleash a bioweapon upon the world that is transmitted by touch and kills its victims based upon their DNA. After a missile strike is launched against Safin’s compound, Bond stays behind to assure that the silo’s blast-proof doors stay open. Bond’s gesture that not only saves the world but allows his current paramour, Madeleine Swann, and the young daughter he never knew he had, to safely escape the island.

Given how much of No Time to Die is pervaded by a sense of grief and sorrow, the decision to include a title song reflective of the film’s solemnity and melancholy makes perfect sense. Like some of the other nominees, Eilish’s tune begins slowly and quietly with a piano plunking out a repeated four note motif accompanied by strings and low brass. Eilish intones the first lyric, “I should have known” in a sung whisper. The serpentine melody unwinds through the verse and chorus, eventually taking Eilish into the upper range of her soprano on the lines:

Fool me once, fool me twice

Are you death or paradise?

You’ll never see me cry

There’s just no time to die

Just as the chorus ends, a thunderous bass chord enters, and the opening four note motif returns. The song continues to build, and more instruments are added as the song reaches its second chorus. Our four-note motif returns once more, but this time played in full orchestral splendor by the strings and the full brass section. The musical bombast ultimately fulfills the remit of other classic Bond songs. Eilish even follows suit by loudly belting out the chorus, revealing a power and huskiness to her voice that most of her fans probably hadn’t heard before.

“No Time to Die” finishes with a coda that returns to the sparse arrangement of the tune heard at the start. Eilish also goes back to the shivery murmur that is her stock in trade for one last iteration of the chorus’ last two lines.

No Time to Die larger themes of love, death, grief, and martyrdom presented a special challenge. Billie and Finneas rise to it beautifully. Moreover, the Eilishes also cleverly incorporate musical elements that evoke the harmonies and tonalities of John Barry’s best-known scores in the series. The four-note motif that serves as a spine for the song sounds like it could have easily been drawn from From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, or Thunderball. They also conclude the song with an electric guitar strumming an EmMaj9 chord, the so-called spy chord that Vic Flick plays at the end of the famous James Bond theme that started it all.

Does this mean that “No Time to Die” is the odds-on favorite to win? Perhaps, but it also seems to be overshadowed by another song, much as “Dos Oruguitas” was. In this case, the song was written for a completely different Bond film and mostly functions as an Easter Egg for die-hard fans of the series. It is “We Have All the Time in the World,” which was written by John Barry and Hal David and performed by Louis Armstrong over the end credits of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1968). Notably, the song appears just after Bond’s new bride, Tracy, has been killed in a drive-by shooting by Blofeld and his assistant, Irma Bunt. It is yet another evocation of death in No Time to Die with Tracy, like Vesper Lynd, implicitly included in the film’s mounting body count. Notably Hans Zimmer’s score for No Time to Die incorporates the melody to “We Have All the Time in the World” in three of the cues he wrote for the film. Indeed, long-time fans like me might well recognize the older Bond song in Zimmer’s score much more readily than the new one specifically written for it.

Prediction for Best Original Song

An Oscar would confer EGOT status on Lin-Manuel Miranda, a distinction held by just a handful of other entertainment luminaries. In fact, because Miranda also won a Pulitzer Prize for Hamilton and a MacArthur Genius Award, an Oscar would place him in entirely unique category. Say hello to the MacPEGOT.

Yet, although an award for “Dos Oruguitas” would make history, recent Oscar ceremonies have favored Bond songs. Adele won for “Skyfall” in 2013. Sam Smith repeated the feat with “Writing’s on the Wall” in 2016. “No Time to Die” also has already won a Grammy, a Golden Globe, and more than a dozen awards from prominent critics’ societies. Eilish is also a newly minted pop star, whose personal story is the kind of underdog narrative that Oscar voters seem to like.

If you are looking for a dark horse in the field, you might consider “Be Alive.” (Although when would you ever consider Beyoncé a dark horse for anything?) But I am sticking with the favorite. On Sunday, I expect Eilish to win. It is the clubhouse leader in terms of the betting markets and also my personal favorite among the field.

An ode to the new cleffer

One of the first things you might notice about this year’s slate of nominees for Best Original Score is the relative absence of the “usual suspects” in the music branch, such as Thomas Newman, Alexandre Desplat, or John Williams. Between them, these three composers have received a total of 78 nominations. Admittedly, only one of the five nominees this year – Germaine Franco – is a first timer. However, aside from Hans Zimmer’s twelve previous nominations, none of the other composers has received more than four.

Franco’s nomination is significant for other reasons. In February, she became the sixth woman nominated for Best Original Score and the first Latina. The field has a decided international flair with nominees from Britain, Germany, and Spain joining two Americans.

Of the five nominees, Alberto Iglesias’ music for Parallel Mothers (above and at bottom) comes closest to the style of a classical score. Yet it also presents a slight departure from those norms in its use of a chamber orchestra with most cues arranged for strings, piano, and the occasional wind instrument. Some feature the strident bowing style associated with Bernard Herrmann’s famous score for Psycho (1960). Others create lush combinations of strings and solo piano, an approach reminiscent of Frank Skinner’s music for older Universal melodramas like All That Heaven Allows (1956).

If that sounds a bit odd, it shouldn’t. Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk have been prominent influences on Pedro Almodovar’s cinema over the years. Parallel Mothers is the thirteenth film that Iglesias has scored for the great Spanish auteur. The composer admits that Almodovar’s films are always rooted in melodrama. But Parallel Mothers also had the generic trappings of a thriller, and his music strived to infuse scenes of psychological intimacy such that they crackled “with energy and light.” Iglesias also sought to accentuate the protagonists’ intertwined lives at a macro-level, using parallel musical structures to underscore how Ana enters and exits Janis’ life at several points in the film.

Iglesias is a four-time nominee and his score for Parallel Mothers is among his best. But I fear this is not his year. Parallel Mothers is among the biggest longshots in the Oscar betting markets not only for Iglesias in the Best Score category but also for Penelope Cruz as Best Actress. Moreover, the fact that Spain snubbed Parallel Mothers when submitting its nominee for Best International Feature Film also doesn’t bode well. Iglesias is once again a very deserving nominee whose work is likely to be overlooked in a highly competitive field.

Stretching the classical style: Incorporating novel idioms

Nicholas Britell earned his third Oscar nomination for Don’t Look Up, Adam McKay’s acrid satire of contemporary politics and media. The film’s dark humor and its apocalyptic conclusion undoubtedly posed a conceptual challenge for Britell. How do you preserve the comedic qualities of the story while still respecting the existential crisis that hints at larger issues around climate change, COVID, and the increasing distrust of science and medicine? As Britell acknowledges, he was “unprepared for the wild ride” that viewers experience over the course of the film. Britell’s solution? A hyperbolic paean to science, a smattering of wacky electronic sounds, some rollicking big band jazz, and garage-band style Farfisa organ.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Britell notes that two cues were especially important in articulating the overall concept for the score. Even before production had wrapped, Britell created a demo cue entitled “Overture to Logic and Knowledge” that McKay played on set to enable the cast to get in the right frame of mind.

The piece unfolds as a canon performed on a piano that’s been recorded with heavy reverb. After the statement of the initial theme, Britell interweaves additional voices in contrapuntal harmony, approximating the sort of mathematical precision one associates with Bach fugues. Afterward, Britell then tried to suss out what the opposite of that compositional style might be, eventually landing on big band jazz. The idiom is evident in the film’s main title, which features walking bass, a simple brass and bass saxophone riff, and a soaring trumpet obligato. Another cue – “It’s a Strange Glorious World” – reprises that big band style, yet further estranges the viewer from the serious global crisis dramatized in Don’t Look Up with the use of banjo and toy piano for instrumental color.

Britell saves his most savage musical satire for a theme written for Peter Isherwell, the billionaire tech genius played by Mark Rylance.

The composer arranges the theme for celestas, toy pianos, Farfisa organ, and bass synthesizers. These instrumental colors suggest Isherwell’s childlike faith that new technology can solve all of humankind’s biggest problems. Of course, Isherwell exudes this relentless optimism to mask his real intentions. Isherwell proposes a foolhardy mission to try and capture the streaking comet rather than deflecting or destroying it. He does so to feed his corporate greed as the comet possesses rare minerals that Isherwell hopes to harvest for use in his production of microchips.

Britell’s score displays incredible musical sophistication even as it is asked to underscore scenes that occasionally seem silly or in which the satire seems all too crude. That being said, I have some doubts that it will win for Best Original Score. This is not to gainsay Britell’s extraordinary ingenuity in devising his music. Rather, it is just the brute reality that other films have better odds in what seems to be a close race.

Germaine Franco’s music for Encanto also pushes the bounds of the classical score. In this case, though, it does so by incorporating various styles of Latin pop music rather than using big band jazz. To be sure, there was a strain of this type of composition in earlier eras, Think, for example, of the music written by Henry Mancini, Nelson Riddle, and Quincy Jones for films of the 1960s. That music, though, reflected the predominant Latin pop styles of the period, which included congas, rhumbas, cha-chas, sambas, and bossa novas.

In contrast, Franco drew upon a different repertoire of Latin rhythms to fashion her score for Encanto, including some folk music styles specific to the film’s Colombian setting. These not only include more familiar idioms like salsa, but also more modern developments like reggaeton. The latter is a style that originated in Panama in the 1990s and mixes hip-hop beats with Jamaican riddims. It rapidly spread through Spanish-speaking countries in the Caribbean.

In Encanto, reggaeton can be heard in Luisa Madrigal’s big number, “Surface Pressure.” The song, of course, was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Franco then incorporated the style into certain cues to ensure a strong sense of unity between the mood and vibe of the songs and those of the score.

Other cues, however, are written in folk styles native to Colombia with Franco once again taking her cues from the rhythms of Miranda’s songs. Encanto’s opener, “The Family Madrigal,” is an up-tempo vallenato song played in standard 2/4 meter. It features marimba, three-button accordion, and guachara, a Colombian percussion instrument played by rubbing a fork over a wooden, ribbed stick. Mirabel’s “I want” song, “Waiting on a Miracle,” uses bambuco rhythms. It unfolds in a fast triple meter characteristic of the idiom. As the only song featuring this rhythm, Miranda used it to further underline how Mirabel feels separated from her family due to her lack of a special gift for magic.

Perhaps Franco’s most important gesture, though, was using cumbia rhythms to underscore Mirabel’s movement. Cumbia is popular style throughout South America but has its origins among enslaved African populations on the coasts of Colombia and different Caribbean nations. It uses a clave rhythm common in Afro-Cuban music. As the style spread throughout Colombia in the early 1900s, musicians incorporated indigenous drums and wind instruments, including tambora, llamador, and gaitas. As Franco has noted in interviews, she uses the cumbia to accompany Mirabel’s first entrance into the “Casita.” From that point on, according to Franco, “The rhythm of the cumbia becomes the forward motion of her trying to find a solution to the problem.”

I suspect Franco’s fellow composers in the music branch are as impressed as I am by her attention to details of rhythm and orchestration. To get the precise tone color needed for some of these Latin pop and folk styles, Franco had a special marimba native to the Choco rainforest region of Colombia disassembled and shipped to her in parts. After it was put back together, Franco played the marimba herself, two mallets in each hand.

Encanto isn’t the favorite to take home the prize for Original Score. But if you’re looking for a potential surprise on Sunday night, Franco seems to be in the best position to pull an upset.

Rock of the Westies

Many pop music fans know Jonny Greenwood from his work as a songwriter and lead guitarist in the British rock band, Radiohead. Greenwood, though, has also established a considerable reputation as a film composer. He is perhaps best known for his work with director Paul Thomas Anderson, who has collaborated with Greenwood on his past five projects. Beginning with There Will Be Blood (2007), Greenwood went on to score The Master (2012), Inherent Vice (2014), Phantom Thread (2018), and Licorice Pizza (2021).

In February, Greenwood earned his second Oscar nomination for Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog. Much like the rest of the film, Greenwood’s score works against many of the conventions of the classic Hollywood Western. Many studio-era oaters developed their scores around orchestrated versions of tunes in the cowboy songbook or around Coplandesque rhythms and harmonies. Both these approaches strived to evoke the majesty of the films’ visuals, which often featured mountain vistas, endless prairies, and sunlit horizons.

Instead of looking to the “sweeping strings” style used in older Westerns, Greenwood was inspired by the atonal brass music that was used in old Star Trek episodes to underscore the exploration of unknown planets. When Peter ventures into the mountains and discovers a dead cow, Greenwood accompanies these scenes with a dissonant French horn duet to highlight the strange and forbidding quality this has on the impressionable teenager.

Similarly, instead of a big string sound, Greenwood opted for smaller ensembles, occasionally writing things for six cellos or four violas. Greenwood also plucked strings of a cello as a correlate for Phil’s onscreen banjo playing. Here again, the goal was to create a tone color that seemed just slightly off, emphasizing microtonal inflections to create a sound that was somber yet sinister.

Phil’s banjo playing also furnishes one of the most memorable scenes in The Power of the Dog. Peter’s mother, Rose, initially seems ill at ease after coming to live with George and Phil on the brothers’ ranch. At one point, she seats herself at the piano and proceeds to struggle through a piano reduction of Johann Strauss Sr.’s “Radetzky March.” Campion then cuts to Phil sitting in his bedroom offscreen. Phil then picks up the melody of the Strauss piece on his banjo, playing it almost effortlessly and improvising his own coda. In a test of wills, Phil’s virtuosity humiliates Rose, who increasingly turns to alcohol to soothe her emotional wounds.

Because of this scene, Greenwood used a detuned mechanical piano as a musical timbre associated with Rose.

To produce this effect, Greenwood used computer software to create the sound of a piano roll for his pianola. Then, as the music was played back, Greenwood used a tuning wrench to slightly alter the pitches to create a sound akin to the honkytonk pianos scene in the saloons of older Westerns. For Greenwood, the sound proved perfect for Rose’s character arc. As he states in an interview for Variety, “Not only is her story wrapped up in the instrument, but it was also a good texture for her gradual mental unraveling. I recorded hours of this stuff – poor Jane (Campion) had to hear quite a lot of it.”

Greenwood’s modernist take on the typical Western score makes him one of the top contenders in this year’s Oscars. Of course, it doesn’t hurt that Greenwood wrote music for two other nominated films: Licorice Pizza and Pablo Larraín’s Princess Diana biopic, Spencer. The betting markets have Greenwood as a longshot. However, since The Power of the Dog leads the field with a dozen nominations in all, Greenwood could prevail in the event of a Dog sweep.

Today’s sounds for tomorrow’s people

The last nominee for Original Score is the current favorite. Hans Zimmer earned his thirteenth Oscar nomination for Dune, Denis Villeneuve’s big budget adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic science-fiction novel. As Zimmer notes in a New York Times profile, he self-consciously rejected the musical style associated with the Star Wars series and its many imitators. Those scores looked to the past for inspiration, finding it in Gustav Holst, Igor Stravinsky, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and even Benny Goodman. Instead, Zimmer set himself an almost impossible task, trying to create sounds that no one had ever heard before.

The result is a score that Darryn King calls “one of Zimmer’s most unorthodox and most provocative.” The composer reports that he spent days contriving new sounds, sometimes commissioning the construction of new instruments or using conventional instruments in extremely unusual ways to get the effect he desired. Although synthesizers keep the score rooted in Zimmer’s pop music past, he combines these with several unusual sonorities that include Irish whistles, Indian bamboo flutes, and metallic scraping noises.

Many of these instrumental choices are keyed to aspects of Dune’s intergalactic setting. The rumble of distorted electric guitars evokes the seismic shifts occurring beneath the desert sands on the planet’s surface. Zimmer even used some of the environmental details to communicate what he wanted from the musicians performing on the soundtrack. Slide guitarist David Fleming reports that Zimmer told him for one cue, “This needs to sound like sand.”

Zimmer performed similar wonders in his use of other instruments. For the scene where the House of Atreides arrives on Arrakis, Zimmer recorded thirty bagpipes playing in a Scottish church. The added reverberance raised the volume of the ensemble to ear-splitting levels of 130 decibels. The highland players needed to wear earplugs to avoiding damaging their hearing. But Zimmer got the sound he wanted, the musical equivalent of a blaring air raid siren.

Zimmer’s desire to find new sounds not only altered the usual timbres of instruments but also of the voice as well. For Dune, Zimmer engaged the services of music therapist and singer Loire Cotler. To create the qualities Zimmer was seeking, Cotler drew on several non-Western singing styles. Her syncretic method combined Jewish niggun, South Indian vocal percussion, Celtic lamentation, and Tuvan throat-singing. The end result was a hybridized style that sounded wholly unique: a war cry expressed as though it were an ancient antecedent of Esperanto. Cotler tried to find a name for the new vocal technique, ultimately settling for the person responsible; she called it the “Hans Zimmer.”

Perhaps Zimmer’s most audacious gesture involved hiring winds player Pedro Eustache to build new instruments from scratch. Eustache created a 21-foot horn, a sort of modern version of the old animal horns fashioned into shofars and zinks during the Middle Ages. He also produced a contrabass version of the duduk, which King described as a “supersize version of the ancient Armenian woodwind instrument.”

What does it all add up to? A score that hits all the right notes in transposing Herbert’s imposing epic to the big screen. Zimmer’s music is at times quietly menacing, somber and pensive at other moments, and brooding but anthemic for Dune’s big action scenes. Zimmer’s score for Dune does not depict the kind of triumphalism found in Star Wars or other space operas. Rather, it opts to capture the elements of dark mysticism and doleful psychedelia that made Herbert’s novel a literary head trip in the 1960s. To be sure, Zimmer’s music doesn’t concoct earworms to evoke the sandworms. Yet it succeeds admirably where others have failed nobly. (If you think this is easy, just watch and listen to David Lynch’s misbegotten adaptation from 1984.)

Prediction

One could easily make the case for Germaine Franco to win for Encanto. The score and the album have dominated the popular music scene ever since the film was released in late November. Yet Dune stands a good chance at claiming several other craft awards, such as those for Sound and Production Design, which bodes well for Zimmer’s chances on Sunday.

In the world of film music today, the Burgomeister of Bleeding Fingers Music casts a shadow over the field as large as any of the luminaries who preceded him like Ennio Morricone, Jerry Goldsmith, or Dimitri Tiomkin. When I contemplate the sheer number of innovations Zimmer made in the music he composed for Dune, I can’t bring myself to bet against him. I think Hans takes home the Oscar on Sunday. He’ll walk away with another hunk of metal to scrape for the Dune sequel.

Once again, I want to give a shout-out to Jon Burlingame for his excellent coverage of Hollywood and international film music for Variety. As a subscriber, I always enjoy reading his work for the venerable trade journal, not just during awards season but year-round.

The Diane Warren interview with USA Today that I referenced can be found here. Additional interviews with Deadline and Gold Derby are found here and here.

Interviews with Lin-Manuel Miranda discussing the songs he wrote for Encanto can be found here , here, and here.

Vulture published a nice piece on the process of writing the title song for No Time to Die, which can be found here.

Alberto Iglesias discusses with work with director Pedro Almodovar here .

Nicholas Britell talks about his work Don’t Look Up with Indiewire and Variety here and here . One can find several interviews with Germaine Franco about her process on creating the score for Encanto. A sample can be found here, here, here, and here. A movie score suite featuring Franco’s themes for Encanto can be found here.

Jonny Greenwood talks with Variety about his collaboration with Jane Campion here and here.

The indie-music website provides an interesting review of Greenwood’s soundtrack for The Power of the Dog here.

Finally, Darryn King’s superb overview of Hans Zimmer’s score for Dune can be found here.

Parallel Mothers

Lau Kar-leung: The dragon still dances

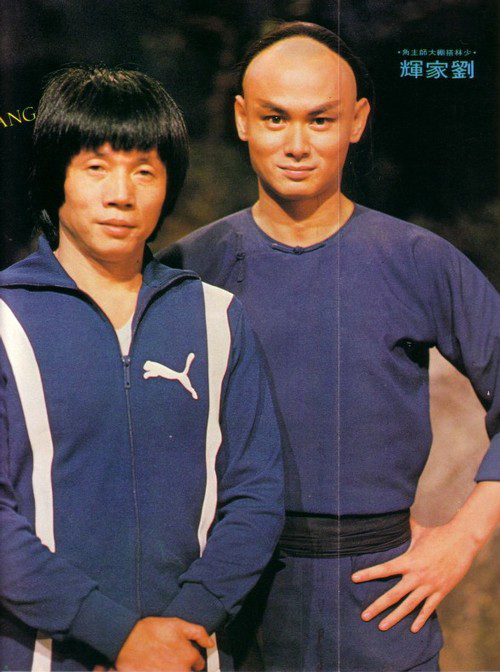

Lau Kar Leung (aka Liu Chia-liang, 1936-2013); Gordon Liu Chia-hui (aka Lau Kar-fei, 1955-).

DB here:

Back in 2020, I was asked to prepare a video lecture on the Hong Kong filmmaker Lau Kar-leung. Under the auspices of the Fresh Wave festival of young Hong Kong cinema, a retrospective and panel discussions were sponsored by Johnnie To Kei-fung and Shu Kei. The event took place in summer 2021. Tony Rayns also participated, offering a deeply informative talk that’s available here, but mine was not included. At a time when I hope people will continue to remember all that Hong Kong popular culture has given us, I’ve recast it as a blog entry.

For some years I’ve been arguing that the martial arts cinema of East Asia constitutes as distinctive a contribution to film artistry as did more widely recognized “schools and movements” of European cinema like Soviet Montage and Italian Neorealism. The action films from Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have revealed new resources of cinematic technique, and the filmmakers have influenced other national cinemas. The power of this tradition is particularly evident in Hong Kong cinema’s wuxia pian (films of martial chivalry), kung-fu films, and urban action thrillers from the 1960s into the 2000s.

Chinese martial arts are well-suited to the movie screen. The performance discipline, seen both in the martial arts and in theatrical traditions borrowing from them, yields a patterned movement that lends itself to choreography. The staccato quality of motion yields a pronounced pause/burst/pause rhythm that can be displayed and enhanced by film technique, as we’ll see.

These aspects of martial arts were captured by filmmakers working for the Shaw Brothers studios between 1965 and 1986. They cultivated a local style that yielded films that looked unlike any others. Thanks to the immense resources of the Shaw Movietown studio, complete with big sets and collections of costumes, the new filmmaking style was given a unique force. With The Temple of the Red Lotus (1965) and Come Drink with Me (1966), what Shaws called its “action era” began, and thanks to international distribution Shaws’ swordplay films gained audiences around the world.

Shaws’ Big 3

Shaw Movietown main office, 1997. Photo by DB.

The new trend benefited from Chinese opera traditions and the martial arts novels of Jin Yong, pen name of Louis Cha Leung-yung. They also owed a debt to Japanese swordplay films, many of which Shaws distributed and urged their directors to study. There was as well the influence of Italian Westerns. Just as important was Shaws’ investment in color and widescreen processes. Updating technology not only allowed the films to compete on the world market; it offered rich opportunities for artistic expression. (See the essay “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic adventures in Hong Kong.”)

Shaws directors quickly established conventions of the new swordplay film. Conflicts, of course, were expressed through combat, at least three major ones per film. One source of friction was the rivalry between martial arts schools run by masters; there might also be competition among traditions, regions (northern/southern), or nations (China vs. Japan). Typically there would be a hierarchy of villains, with our protagonists fighting them in turn. Plots would be more episodic than is typical in Western films. A looser structure favored including extensive set pieces of training or combat that were the appeal of the genre. And the plot would culminate in a long climactic fight, often to the death. These conventions, consolidated in the wuxia pian, carried over into the kung-fu films of the 1970s.

Two directors played central roles in shaping these conventions, and each had a distinctive approach to them. The vastly prolific Chang Cheh (Zhang Che) dominated the Shaws lot. He favored violent plots turning on revenge and intense male camaraderie, in which the martial arts served as a drama of loyalty or betrayal, friendship or deadly enmity. At the same period King Hu Chin-Chuan created one of the breakthrough “action era” works, Come Drink with Me, which immediately established a very different authorial vision. Hu was interested in historical and political intrigue, women warriors no less than male ones, and the martial arts as a spectacle of cinematic grace. Most of his major works, including A Touch of Zen (1971) were produced after he emigrated to Taiwan, although some were distributed by Shaw Brothers.

Neither Chang Cheh nor King Hu was trained in the martial arts, so they relied on choreographers to supply their action scenes. By contrast, Lau Kar-leung was a martial arts director who came to Shaws in the 1960s and choreographed many films for Chang and others. He took over directing duties in 1976 with The Spiritual Boxer and directed over twenty-five films for Shaws until 1985, when the company ceased producing theatrical features. He went on to direct several one-off projects until 2002.

Lau took the uniqueness of martial arts traditions more seriously than other directors, building entire films around one school or another, or among the contrast of rival traditions. He often opens the film with an abstract prologue showing off characteristic moves and tactics of the style that the film will treat. Unlike Chang, he is less concerned with male loyalty and violent revenge and is more inclined toward redemption and forgiveness. He shares Hu’s refined conception of film technique, but he is less overtly innovative. He refined stylistic conventions that were already in place at Shaws and many of which were basic to world cinema storytelling.

For example, Lau accepted the elevated production values demanded by the Shaw product. His films are filled with elaborate sets, both interiors and exteriors, and rich color values. He also recognized the power of editing, something that King Hu had brought to the fore. In the rest of this entry, I’ll concentrate on four of Lau’s distinctive innovations in the Shaws style.

Filling the wide frame

All widescreen filmmakers faced the problem of filling the spacious frame. (See CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses” for discussion of American solutions.) The big Shaws sets enabled filmmakers to pack the frame with figures and settings. We therefore find plenty of dense long-shot compositions.

We also find flashy closer views. Chang Cheh was particularly fond of low-angle medium shots, which he considered “warmer” than straight-on or high angles (The Assassin, 1967; choreographed by Lau).

Hong Kong directors relied on “segment shooting” for action scenes. Instead of overall coverage, with repetitions for different camera angles (the US norm), they plotted the fighting moves for specific camera angles and shot them separately. By calibrating the performers’ actions to the camera setup, they created a unique blend of martial arts techniques with film techniques. Rather than simply record martial-arts movements, filmmakers “cinematized” them.

Lau seems to have taken particular pleasure in filling his frames in ingenious, fluid ways. He enjoyed the challenge of staging combat scenes in confined spaces, so that he couldn’t rely on expansive vistas. Partly, this tactic enabled him to show how different moves were required in close quarters. One of his favorite sequences was in Martial Club (1981). He explained:

Gordon Liu is fighting Johnny Wong in an alley that narrows from 7-foot to 2-foot wide. The physical limits of the alley actually make the best showcase for the different boxing schools. How do you fight in a seven-foot-wide alley? You use big arm and leg movements. Going down to five-foot wide, you keep your elbows close to your body because you don’t want to expose yourself. Further down to three-or-four foot wide, you use Iron String Fist. Finally when you get down to two-foot wide, you engage the “sheep trapping pose.” The results were sensational.

At the same time, the narrowing alley offered rich opportunities to fill the frame with body parts and abstract slices of walls.

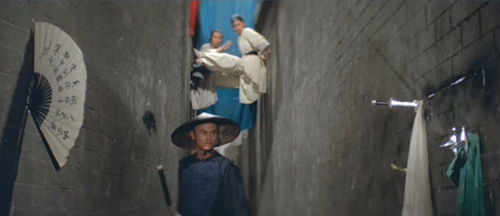

Something similar occurs in Legendary Weapons of China (1982), where two assassins must hide in an alley above a third. This time Lau uses some props to fill out the wall areas.

Lau delights in the possibilities of close fighting in any space. Sometimes the confinement isn’t a matter of setting; it’s dependent on letting the film frame itself constrain the action. Take a portion of a sequence from Dirty Ho (1979). The Prince (in disguise) calls on Mr. Fan, who tries to attack him, all the while pretending to play the host by offering wine.

Establishing shots lay out the zones of action to come, the chairs the men will occupy. Even a momentarily unbalanced framing is compensated for by movement in the empty area.

The first phase of the scene takes place in much closer framings, often tight two-shots. It’s here we see Lau’s virtuosity in finding constantly fresh ways to fill the frame, with compositions always picked for maximum clarity: that is, in showing Fan’s aggression and the Prince’s resourceful blocking, sometimes with comic symmetry.

The pause/burst/pause rhythm gets played out in low angles, with slight camera movements to adjust to the gestures.

The two major props, the fan and cups, get a real workout as they participate in the constant ballet of arms, faces, and fingers. All areas of the screen get activated: top, bottom, corners and sides.

Later in the scene, in a passage I haven’t included in the clip, the servant gets to take part, so now even more body parts are spread across the frame–and a cup even comes out at the viewer.

The scene ends with a comic commentary on the props: master and servant collapse at the table as a cup overturns.

This “close-up action scene” is as fully designed for the widescreen as any expansive long-shot sequence might be, but there’s a particular enjoyment to be had in seeing how a director can do so much with simple components.

Editing: Analytical cutting

Contrary to what many think, Chinese action pictures rely heavily on editing. At Shaws, King Hu pioneered extremely rapid cutting, reducing shots to half a second or less. Lau became a rapid cutter as well; his films from the 1970s and 1980s typically average three to five seconds per shot, with some films containing over 1000 shots.

It’s commonly said that Hong Kong martial arts films favored full shots and long takes, the better to respect the overall dynamic of the combat. Full shots, yes; but not necessarily long takes. While Western directors tended to believe that long shots had to be held quite a bit longer than closer ones, Hong Kong directors realized that long shots could be cut fast if they were carefully composed for quick uptake. Lau’s mastery of composition stands him in good stead when he starts putting shots together: every combat, even the fast-cut ones, are crystal-clear in their execution.

Directors across the world had settled on two major editing resources: analytical cutting and constructive cutting. The first type shows the overall spatial layout of a scene and then analyzes it into partial views. Our Dirty Ho sequence is an example. Constructive cutting deletes the establishing shot and relies on other cues to help the viewer build up the scene mentally. Hong Kong filmmakers made extensive use of both types, and as you’d expect Lau is a master of each.

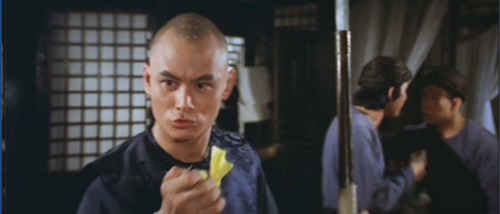

Most Hong Kong directors used analytical editing to favor the actors, to pick out their reactions to the ongoing action. Lau does this as well, as is seen in Dirty Ho. As you’d expect, Lau also uses cuts-in close views to emphasize combat tactics. In Challenge of the Masters (1976), after a villain (played by Lau) has felled his opponent, analytical cuts build to a revelation of a metal attachment to his shoe.

Executioners from Shaolin (1977) illustrates how Lau uses analytical editing during a large-scale fight scene. It’s far less constrained than the tabletop action of Dirty Ho, but he does find ways to narrow the action to particular zones. This is done through cuts to closer views–sometimes very close ones. And the editing is swift, with the average shot lasting only four seconds.

The scene’s opening establishes the hero Hung Hsi-kuan arriving at Pai Mei’s temple. There are two establishing shots, one a pan-and-zoom that presents the temple as Hung arrives, while the other (below) is a zoom back keeping the temple and Hung in the same frame. Both compositions stress the steep stairs leading up the hillside.

Once Hung starts up the stairs, more establishing shots reveal him surrounded. Lau indulges in a feast of different angles, stressing Hung’s vulnerability.

The scene’s second phase follows Hung’s progress up the steps. His encounters with many defenders are captured in a variety of angles, all of them orienting us to the changing situation. (At the top, he’ll encounter Lau himself, wielding a jointed staff.)

Camera setups on the steps themselves keep us aware of the forces arrayed around him. And the steps function a bit like the alleys in other films to limit the range of action.

The camera really penetrates the action, picking out details in the sort of tightly packed framings we saw in Dirty Ho.

Lau remarks: “You can get wonderful scenes of two pairs of hands folding and sliding in and out of each other’s grip.” This sort of tangible physical action is central to Lau’s scene analysis.

Analytical editing can include matches on action, cuts that let movement carry over across shots. Lau gives a virtuoso example in a match-on-action between extreme long-shots of a man in blue sent sprawling. The second shot ends with a zoom back.

It’s possible that Lau used two cameras for coverage of this, but that was a rare option in Hong Kong. It’s just as likely he managed the cut by repeating the fall, a movement stressed by a zoom back.

Again, you get a sense of a filmmaker challenging himself by setting up problems he will need to solve through mastery of his craft.

Editing: Constructive cutting

Trampolines and mattresses in shed on Shaw Movietown lot. Photo by DB.

The wuxia tradition features exponents of the “weightless leap,” the ability to spring very high into space. Before the advent of wirework and CGI, these soaring warriors were treated through editing that shows the leap in a series of shots. For instance, constructive cutting in Chang Cheh’s Golden Swallow (1968, choreographed by Lau) shows Silver Roc launching himself, soaring, and descending on his victim.

The jump was probably facilitated by a trampoline. On the screen, though, we see portions of the action that we assemble in our heads.

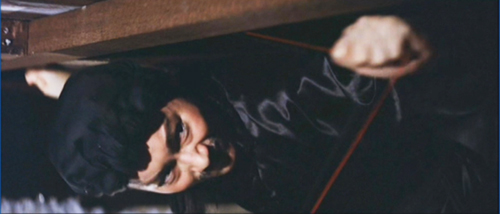

With his usual ingenuity, Lau sought out situations where he could test his skill with constructive editing–not just weightless leaps but combats among fighters at some distance from each other. My example is a brilliant sequence from Legendary Weapons of China (1982). (It takes place in semidarkness, so you may wish to adjust the brightness of your monitor.) Two rival assassins clash in a loft as they try to kill a third in the bedroom below. There ensues a three-way fight, pursued mostly through careful constructive editing.

There are a few establishing shots situating Ti Hau and Fan Shao Ching (disguised as a man) in the loft, but once they change their locations, most of the combat is given through constructive editing. That technique relies on cues of setting and character behavior (body position, facial expression, eyelines), and these are all mobilized early in the scene.

Details of props help us understand the action as well: the two threads bearing hooks and especially the gag with gas.

Once the assassin Ti Tan arrives on the floor below, pure constructive editing takes over. There’s no framing that includes him and his two attackers.

So Lau proceeds to cut together an ongoing fight upstairs (complete with fake meows) with Ti Tan’s suspicions downstairs.

The scene culminates in Fan and Ti Hau fleeing as Ti Tan, still suspicious, doubts that all the noise above him was created by a cat–and even the cat is presented through constructive editing.

In a sequence of 126 shots, the average is about two seconds, but each one is legible at a glance and carries the scene forward with utter smoothness. Lau’s precision in shot design serves him well when we have to assemble the action in our minds.

The smash zoom

Hong Kong action films of the 1960s are notorious for their use–some would say, over-use–of zoom shots. Yet at the time directors throughout the world were exploring the artistic possibilities of zooms. Most notable was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who coordinated the zoom with complex movements of actors and the camera. So we ought to consider the possibility that the zoom in Hong Kong was more than a technical gimmick to spice up action scenes.

For example, a smash zoom can accentuates the pause/burst/pause pattern of the fight. During one combat in Chang Cheh’s The Blood Brothers (choreographed by Lau), the zoom emphasizes sudden bursts of action by whipping back from a fighter.

Alternatively, the zoom can play up the pause by calling attention to moments of stasis. Here a cut emphasizes the pause as the fighters’s weapons are locked before the fight resumes with a zoom back.

In such ways the zoom can break the fight into discrete stages. A far more elaborate instance takes place in Lau’s Return to the 36th Chamber (1980). Chu Jen-chi has painstakingly learned kung-fu at the temple through an apprenticeship of lashing bamboo poles together to make scaffolding. Accordingly, his technique is based on this very particular set of skills. I concentrate on the early stretches and the clip gives you some extra niceties. The whole thing is exhilarating to behold, thanks partly to energetic zooms.

Early on, the zoom introduces us to the lashing technique by showing the robe’s ripped fabric as a kind of handcuff.

Again we see Lau’s interest in watching how hands work, but here it becomes a specific combat tactic. The ensuing action will revolve around hands and wrists, and Lau’s zooms set up a question: What is Chu’s overall strategy?

The answer comes in a series of variations. First, Chu lashes his adversary to a bamboo pole like captured wild game.

Variation 2: Ensemble work. Chu takes on a batch of men, trussing them up horizontally.

He turns out to have in mind an engineering project, a sort of hitching post of miscreants. It’s capped by a shot of one of the Manchu bullies seeing his disciples’ wiggling fingers.

Variation 3: More ensemble work, now vertical, with the men’s wrists stacked like a bouquet.

Again, a master shot reveals the result and another close-up shows their wiggling fingers.

The kung-fu is of course extraordinary, but it takes an unusual cinematic imagination to heighten such elaborate patterns of movement in ways that are perfectly clear. Chu’s display of serious efficiency has a humorous side, capped by the gags that show the villains utterly flummoxed. We should ask if today’s action sequences in American films have this sort of unforced rigor and exuberance.

In the mid-1980s Shaw Brothers eased out of theatrical filmmaking, devoting Movietown to television production. Lau went on to one-off projects, some of which (e.g., Tiger on Beat, 1988) are well worth your attention. (Go here for the astonishing climax.) He had a late-career resurgence as choreographer for Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005). But his prime achievements, I think, will remain his vastly entertaining and filmically rich Shaws classics. His dedication to the specifics of martial arts lore, his unique sense of comedy, and not least his precise direction brought unique qualities to the remarkable tradition of Asian action cinema.

Chang’s remark about “warm” low angles is in Chang Cheh, A Memoir (Hong Kong Film Archive, 2004), 82; he discusses shooting The Assassin on p. 86. Lau’s comments on Martial Club come from “We Always Had Kung-Fu: Interview with Lau Kar-leung,” in Li Cheuk-to, A Tribute to Action Choreographers (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006), 62; the remarks on hands are on p. 59.

I discuss Lau further in both Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and in this blog entry.

Lau as the drunken master in Heroes of the East (1978).

Sergei Loznitsa and the Ukraine invasion

Donbass (2018).

DB here:

Of the many gifted post-Soviet-era filmmakers, one has emerged prominently in response to Russia’s invasion of the country. Sergei Loznitsa was born in Belarus, grew up in Ukraine, and now lives in Germany. Long a harsh critic of Putin’s regime and the Soviet communism that preceded it, he recently resigned from the European Film Academy, citing its lukewarm response to the atrocities in Ukraine. Here is the full text of his letter, as published in Screen International (28 February).

What a shameful text has been generated by the European Film Academy! “The invasion in Ukraine is heavily worrying us”.

When, in the spring of 2014, Oleg Sentsov was arrested, you wrote to the Russian authorities asking them to “consider this matter carefully and fairly”.

Is it really possible that after 8 years of war you still remain blind and continue to mutter some gibberish about the fact that a “daily increase of tension has an impact on filmmakers’ lives and health, morale, and creative work”.

You state in your address that there are 61 Ukrainian members among your ranks. Well, as of today, there are only 60 of them. I don’t need you “being alert and staying in touch with me”, thank you very much!

You’d better ‘stay in touch’ with your own conscience.

For four days in a row now the Russian army has been devastating Ukrainian cities and villages, killing Ukrainian citizens. Is it really possible that you – humanists, human rights and dignity advocates, champions of freedom and democracy, are afraid to call a war a war, to condemn barbarity and voice your protest?

Today, on February 28, 2022, there can be no more doubt about one thing: the European Film Academy was set up in 1989 in order to bury its head in the sand and to shy away from the catastrophe which is taking place in Europe.

Sergei Loznitsa, filmmaker

The day after Loznitsa’s resignation the EFA issued a stronger statement of condemnation.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

The Trial (2018), for instance, is an unblinking record of an early Stalinist show trial, in which scientists are charged with anti-Soviet sabotage. They read their confessions, but under questioning they seem confused about what they’re admitting to. The whole procedure is conducted with mechanical impersonality, and you watch for any sign that the accused men will crack. Only at the end do titles tell us that their supposed secret organization was wholly a creation of the regime. Likewise, The Event (2015) records citizen mobilization in St. Petersburg during the failed communist putsch against Gorbachev in 1991. It assumes the viewer will understand that the snatches of Swan Lake heard from time to time allude to the fact that Tchaikovsky’s score was broadcast continuously in place of news reports.

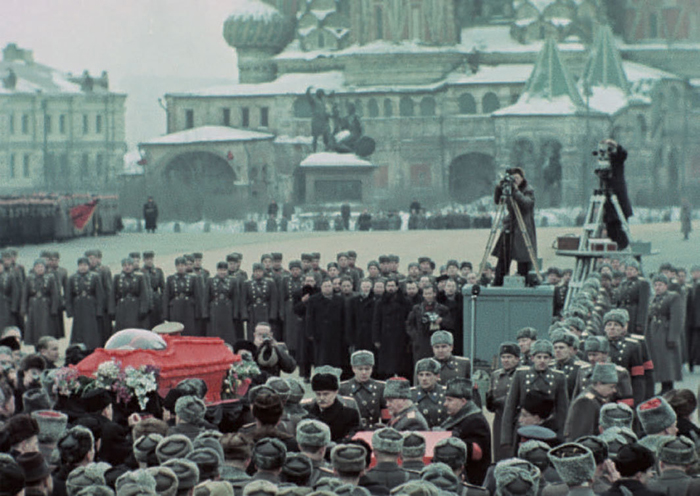

Perhaps most stunning of the documentaries I’ve seen is State Funeral (2019), an assemblage of footage of ceremonies following Stalin’s death. I’ve seen some of this material in other films, but to show the entire panorama of mourning across the Republics, mostly in dazzling color, brings home with crushing near-monotony how a regime can mobilize mass emotion. These people seem genuinely despairing at the loss of the Great Helmsman. The pageantry is at once splendid and appalling.

The three fiction films I’ve seen are bleak. My Joy (2010) follows a Russian truck driver through a landscape of poverty, corruption, and teen prostitution, and invokes World War II through a strange time-warp. In the Fog (2012) rewrites the scenario of the heroic Soviet WWII picture through the experiences of a man caught between both German occupation forces and Belarussian partisans.

Unlike these, Donbass (2018) lacks a single protagonist. It’s a string of scenes based on actual incidents from the 2010s. It shows the ongoing struggle between Putin-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces in Donesk, with ordinary people struggling to carry on. The tone is wider than in the other films, with pathetic scenes alternating with grotesque comedy. An early episode shows a woman stomping into a civic meeting and dumping a pail of shit on a bureaucrat’s head. A bit like Roy Andersson, Loznitsa connects his vignettes by having a character from one linking to the next, or letting an item of setting, such as a black Mercedes, reappear at different points. The whole film is enclosed by a tragic replay of an opening showing the staging of a fake massacre, to be filmed by an obliging official media outlet.

These films are fairly available. All the fiction features are on DVD or Blu-ray. Five of the documentaries (including A Night at the Opera, 2020, which shows a mordant sense of humor) are streaming thanks to Mubi. In the Fog is streaming from Fandor/ Amazon Prime. Some online sites are offering the films, subtitled, for free. The Guardian has made Maidan (2014) available on YouTube for the duration of the war on Ukraine, to support donations to the Ukrainian Army. This film traces the popular overthrow of President Yanukovich in the winter of 2013-2014.

Loznitsa’s films have been accorded many festival awards, in Cannes, Venice, and elsewhere. Sometimes castigated as “Russophobic,” they’re strong, bracing work and they deserve our attention, especially now.

Loznitsa’s website is here. His views of Soviet history are revealed in a spirited interview with Senses of Cinema. At Criterion’s The Current, David Hudson gives an up-to-date report. In The New Yorker Masha Gessen offers a thoughtful review of The Trial. J. Hoberman has an excellent, informative essay on State Funeral in Artforum.

Thanks to Michael Campi for the link to Maidan.

P.S. 7 March 2022: I just discovered this illuminating, detailed review of Donbass by John Bennett at The Movie Waffler.

State Funeral (2019).