Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

A many-splendored thing 11: Portraits

DB here:

Some miscellaneous glimpses of people I’ve run into at the Hong Kong International Film Festival. If the notion of six degrees of separation holds good, chances are you know some of them, or someone you know does.

Up top, the great actor Ti Lung, remembered from Chang Cheh films and perhaps most famous for his role as the honor-bound brother in John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow.

Below, Russell Edwards, Variety critic and reporter, with Bérénice Reynaud, programmer (San Sebastian festival, RedCat), professor (Cal Arts), and critic (author of books on Chinese film and on Hou’s City of Sadness).

Li Cheuk-to, one of Hong Kong’s most distinguished film critics and Artistic Director of the festival. Ah-to is at the center of HK film culture, having founded the Critics Society and played a central role in the festival for decades. This shot on the Star Ferry catches him in an unusual moment of calm; normally he’s doing nine things at once.

Ivy Shiau, Operations Manager of the festival, starting to set up the room for press and guests.

Subway Cinema boys on the go: at Kubrick, Grady Hendrix deals while Goran Topalovic buys books.

On the set of Triangle: Simon Yam chats with Twitchfilm‘s correspondent Todd Brown.

Also on the Triangle shoot: Kelly Lin and Antoine Thirion (Cahiers).

At the reception for the Asian Film Awards: Ho Yuhang (Rain Dogs) and Bong Joon-ho, who would win big with The Host.

Killing time between screenings at an outdoor cafe: Grace Mak, Hong Kong critic doing graduate work at the University of Singapore, and Nat Olsen, film and music maestro. A graduate of UW, he’s dj-ing all over Asia and hosting the site Hong Kong Hustle.

Here’s Sam Ho, Head Programmer at the Hong Kong Film Archive, keeping cool as we wait in line for a screening.

Here’s Yvonne Teh of Penang, huge fan of Asian film and proprietor of the Webs of Significance blog.

Note how my background skilfully keeps the cellphone motif going. Actually, if you photograph anything here but marine life, somebody with a mobile will be in the shot.

Jupiter Wong is the HK film industry’s top still photographer and the wildest man I’ve ever met. Upon meeting me this year, he said, “Why do you look so old?” He has gotten a haircut, but otherwise there’s no sign of domestication.

I met Athena Tsui when I first came to Hong Kong twelve years ago. A graduate of U Toronto, she has worked in many phases of film production, distribution, and exhibition. She routinely helps out the festivals with translation, guest wrangling, and planning. She’s been my supreme guide to HK film insiders’ gossip and to Mongkok shopping.

I couldn’t attend the talk given by Jean-Michel Frodon, editor of Cahiers du cinema, but I did see him outside another event. We first met in Shanghai and keep running into each other at various festivals.

Another old friend, Virginia Wright Wexman of Chicago, was leading a group of visitors to the festival. The smile is doubtless the result of her recent retirement from the University of Illinois–Chicago.

Peter Tsi is the boss of it all, the Executive Director of the Festival. You can usually find him multitasking.

Shu Kei, another friend from my first visit, is head of Film at the Academy for the Performing Arts. He has done everything–made films (see especially A Queer Story), distributed them, programmed the festival, and taught film aesthetics and production. His knowledge of cinema is encyclopedic.

Akiko Tetsuya is a perennial HKIFF presence. She has done a wonderful book on Brigitte Lin.

Shelly Kraicer founded one of the first Chinese cinema websites. He’s a prolific writer and an active consultant on Chinese film for Venice, Vancouver, and other festivals.

The very first person I came to know when visiting the festival in ’95 was the warm and generous Michael Campi. Michael is a pharmacist by trade and a devoted cinephile and festival consultant in his native Australia.

Frederic Ambroisine is an editor of the Paris magazine Kumite and is a busy producer of documentaries on Chinese cinema. If you own French editions of the Shaolin Monastery or One-Armed Swordsman series, you have bonus materials prepared by Fred. Below he’s rejoicing in his purchase of Cutie Honey action figures.

Other folks’ pix can be found if you trawl back through my previous entries. To all those whom I failed to snap, or whose shots didn’t come out well, I apologize. But all the more reason for you to return next year. Fame awaits you!

Speaking of other years….Two regular guests and old friends couldn’t attend this spring, so I can’t resist slipping in shots of them from the 2006 festival. First, Mike Walsh of Flinders University, Australia (and a UW grad).

And here’s Peter Rist of Montreal’s Concordia University, at last year’s launch of the book on Milkyway Image.

Finally, a shot of the wonderful Lisa Lu, star of many Shaws productions and other major pictures, such as Bertolucci’s Last Emperor. You can see her in a Li Han-hsiang frame I posted earlier.

I can hardly believe that the festival is coming to an end. I leave for home on Thursday, but I hope to tack on one more entry before I go.

A many-splendored thing 10: Li Han-hsiang, cont’d

Li and his legend

The Li Han-hsiang retrospective rolls on here at the Hong Kong International Film Fest. For my initial blog on the subject, along with relevant links, go here.

Li is chiefly known for his costume pictures, though he reveals a talent for more intimate fare, as seen in The Winter (1969), which I commented on earlier. His early HK films, like Lady in Distress (1957) and A Mellow Spring (1957), are fairly typical Mandarin-language melodramas, with comparatively high production values and centering on suffering heroines (played in both of these by Linda Lin Dai). The first is a rural romance, with some attractive landscape locations and night-for-night shooting. A Mellow Spring, an instance of the “tenement film” characteristic of 1940s-1950s Hong Kong cinema, takes place over a single day and moves among several families in an apartment bulding.

Li’s direction here is simple and traditional. He uses fairly distant staging, presenting shot/ reverse-shot breakdown of dialogues and camera movements that adjust to the characters’ movements. A moment of tension will be underscored by rapid cutting. There are occasional depth shots, but nothing that would be considered unusual for the 1950s in other national cinemas.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect to western eyes is a habit that Li relies on throughout his career. After a cut, a character may pop into the frame from left, right, or below, usually in close-up. Directors of martial arts films use this tactic in the 1960s and thereafter, but I was surprised to see it in the context of straight drama. It will recur in the Taiwanese films Li directed or supervised. I can’t say if it’s original with him or if he and his subordinate directors took it from another source, but it certainly tends to accentuate the reaction shot. In other directors’ action pictures these abrupt frame entrances becomes part of a captivating overall rhythm of cutting and figure movement.

In 1963 Li moved to Taiwan and founded the Grand studio. As he attests in the archive’s indispensable book, he was a poor businessman and Grand folded in a few years. His most acclaimed achievement there was Beauty of Beauties (1965), a spectacular historical saga. I’d seen it before, but the archive screening offered an opportunity to look more closely. Unfortunately, the original two-part release is unavailable, so a 155-minute version was shown.

It’s certainly an awesome achievement. Two or three exterior sets are enormous and crowded with soldiers, chariots, and masses of commoners. Clearly Beauty of Beauties was an effort to rival the behemoth pageants of Hollywood. The central plot, however, isn’t very visible in the shorter version. King Fu Chai has conquered the kingdom of Yueh, so Yueh’s king sends Hsih Shi, a beautiful village girl, to Fu’s court to seduce him. She succeeds in weakening the influence of his counselors, and after seventeen years (!) Yueh’s king gains the strength to rebel against the oppressors. The problem is that in making the short release version, the editors played up the scenes of crowd spectacle and took out most of the palace intrigue. The result is choppy, with some scenes interrupted midway and little effort to trace Hsih Shi’s growing sway over Fu.

More satisfying, in a lowbrow way, were Grand items like Storm over the Yangtse River (1971), a thriller in which Chinese guerrillas fight the Japanese occupation in the 1930s. Lots of spy-vs.-spy trailing, double-dealing, and bluffing are at the center here. The most Wellesian of the Li films I saw, this is full of steep angles and shock cuts. A good visual idea was the towering inn set, which allows Li to show action on different staircase landings simultaneously. Clearly he could direct unpretentious entertainment when he wanted to.

More satisfying, in a lowbrow way, were Grand items like Storm over the Yangtse River (1971), a thriller in which Chinese guerrillas fight the Japanese occupation in the 1930s. Lots of spy-vs.-spy trailing, double-dealing, and bluffing are at the center here. The most Wellesian of the Li films I saw, this is full of steep angles and shock cuts. A good visual idea was the towering inn set, which allows Li to show action on different staircase landings simultaneously. Clearly he could direct unpretentious entertainment when he wanted to.

Li and his league

Just as interesting as Li’s own Taiwanese pictures are those he supervised. Of the ones I saw, three were directed by Yeung So, and they offered instructive early examples of the contemporary melodrama called chiungyao films.

Chiung Yiao (Qiong Yao) was a popular writer of romance novels, and she gave her name to an entire genre of fiction and film. Probably the most famous chiungyao movie is Outside the Window (1973), starring Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia and centering on the forbidden love between a teacher and his student. Other chiungyao films I’ve seen center on cross-class romances or the miseries of the well-to-do. The rich young people listen to rock and roll and drive Vespas, and they live in modernistic houses with well-stocked bars and doily-covered armchairs. Chiung Yao’s work helped Taiwanese cinema attracted a new generation of viewers while showcasing a self-consciously modern Taipei culture.

Yeung So’s Many Enchanting Nights (1966), for Grand, was an early Chiung Yao adaptation. At first it seems to be about a high-school girl from a struggling family who falls in love with a rich man’s nephew. Gradually the narration shifts toward her parents and their domestic tensions, which revolve around the wife’s youthful love affair with the wealthy man. A long flashback fills us in on the backstory, and the weight of the film falls on the mother, who suffers not only abandonment by her lover (through a misunderstanding) but merciless attack by her self-destructive husband. Released in two parts, Many Enchanting Nights is a deliberately paced but always enjoyable exercise in suffering, miscommunication, flashes of lurid teen sexuality, impotent male rage, and female fortitude. There are many accessory pleasures as well. When our young lovers visit a bar, the theme from Johnny Guitar is rendered on electric guitar.

Yeung So’s Many Enchanting Nights (1966), for Grand, was an early Chiung Yao adaptation. At first it seems to be about a high-school girl from a struggling family who falls in love with a rich man’s nephew. Gradually the narration shifts toward her parents and their domestic tensions, which revolve around the wife’s youthful love affair with the wealthy man. A long flashback fills us in on the backstory, and the weight of the film falls on the mother, who suffers not only abandonment by her lover (through a misunderstanding) but merciless attack by her self-destructive husband. Released in two parts, Many Enchanting Nights is a deliberately paced but always enjoyable exercise in suffering, miscommunication, flashes of lurid teen sexuality, impotent male rage, and female fortitude. There are many accessory pleasures as well. When our young lovers visit a bar, the theme from Johnny Guitar is rendered on electric guitar.

The flirtation with incest in Many Enchanting Nights comes out with force in another Chiung Yao adaptation, Yeung So’s The Stranger (1969). A college girl is shadowed by a mysterious older man, and after he introduces himself she starts to fall in something like love with him. But flashbacks reveal to us that this attraction is, to say the least, misplaced. One odd aspect of this movie is the fact that until the climax we never see the face of the girl’s mother; her back is to us, she’s in shadow, or she doesn’t get a reverse-shot. Did Wong Kar-wai borrow this for his oblique portrayal of the spouses in In the Mood for Love? Like Many Enchanting Nights, The Stranger shows a flair for striking ‘scope compositions and saturated color design. And again we get those pop-in and pop-up frame entrances.

The flirtation with incest in Many Enchanting Nights comes out with force in another Chiung Yao adaptation, Yeung So’s The Stranger (1969). A college girl is shadowed by a mysterious older man, and after he introduces himself she starts to fall in something like love with him. But flashbacks reveal to us that this attraction is, to say the least, misplaced. One odd aspect of this movie is the fact that until the climax we never see the face of the girl’s mother; her back is to us, she’s in shadow, or she doesn’t get a reverse-shot. Did Wong Kar-wai borrow this for his oblique portrayal of the spouses in In the Mood for Love? Like Many Enchanting Nights, The Stranger shows a flair for striking ‘scope compositions and saturated color design. And again we get those pop-in and pop-up frame entrances.

The most renowned Grand film that Li Han-hsiang supervised is At Dawn (1968), by Song Cunshou. It’s a restrained but shocking attack on Chinese trial procedures. A young man goes off to his first day as a bailiff and is appalled by the fact that torture is used to extract confessions. Will he accept this for the sake of keeping a job, or will he quit? Unusually subdued, set mostly at night and in darkened interiors, At Dawn is a remarkable study of weakness and bad faith, and it deserves its fame as a Taiwanese classic.

Li and his lens

At the beginning of the 1970s, when he returned to Hong Kong, Li Han-hsiang was apparently settling into the style that would characterize his work for many more years. He was cutting faster. Lady in Distress and A Mellow Spring are shot in leisurely fashion, averaging, respectively, 10.4 seconds and 16.1 seconds per shot. In the late 1960s, The Winter comes in at 6.5 seconds, Storm over the Yangtse River runs 4.7 seconds average, and Li’s episode of Four Moods (1970) averages 4.6 seconds per shot. Of the late films I’ve seen in the retrospective, the averages run from about five seconds down to less than three (in Passing Flickers, 1982). These shot lengths are comparable to the quick cutting in the kung-fu films of the period.

As often happens with accelerated cutting, close-ups of the actors now predominate. Li likes to treat conversations in enormous facial views (not always in focus), quickly intercut on lines of dialogue. We still get the sudden frame-entrance cuts. And he really, really likes zooms.

Li’s reliance on zooms has often been condemned as laziness or opportunism, and there’s some evidence for this judgment. He astonished everyone by the speed with which he worked, churning out erotic tales, gambling comedies, and costume pictures. He recruited Lam Chiu-ha as cinematographer because Lam could finish 100 shots in a day. The zoom facilitated quick work, and Li evidently didn’t see it as looking tackier than a tracking movement. On one shot he asked Lam, “Why did you use a dolly? Wouldn’t a zoom-in be sufficient?” (1)

Nowadays the zoom is flourishing, serving to provide pastiche (Tarantino in Kill Bill) (2) or add “energy” to a scene. But in the 1970s it was associated with cheap and/or incompetent filmmaking. That wasn’t entirely fair: Truffaut and Rossellini had made good use of it in the 1960s, and Visconti, Fellini, Bergman, Satayajit Ray, and other major directors were relying on the zoom at about the time that Li was. So were most Shaw directors, notably Chang Cheh. I argued in Planet Hong Kong that martial arts directors like Chang integrated the zoom into the staccato rhythm of combat scenes. No technique is inherently cheesy or superb; everything depends on how it’s used. Does Li do creative things with his zoom?

Not as far as I can see. Sometimes he just zooms in to capture his beloved close-ups, or to create an explosive punctuation (as in kung-fu films). At other times, he uses the zoom, along with panning movements, to break down or reestablish the dramatic space, in the manner of Rossellini’s Rise to Power of Louis XIV (1966). In The Empress Dowager (1975), the young eunuch Kuo (David Chiang) acknowledges that he’s been sent to spy on the emperor (Ti Lung). As the emperor dismisses him, we zoom back.

Kuo leaves, and the emperor looks after him as the camera zooms to an even fuller framing.

The emperor turns away and walks to the right, the camera panning to follow.

Once the characters are settled into a new arrangement, Li zooms in on one advisor as he talks with the emperor.

Played out in a single shot, the passage uses the zoom to substitute for cut-in close-ups. To get fresh angles on his players Li doesn’t change the camera setup but rather makes them shift position. The pan-and-zoom combination can be found in many 1970s films, from Hong Kong and elsewhere.

Most commentators have considered Li’s erotic comedies of the 1970s and 1980s an embarrassment, but the Archive retrospective has unabashedly included several of them. It has also run the peculiar Passing Flickers (1982), a collection of comic and erotic scenes set in a film studio. Based on a column Li wrote for local newspapers, the film can’t be called good, but it does have fun revealing the bumbling and egotism of mass movie production.

Most commentators have considered Li’s erotic comedies of the 1970s and 1980s an embarrassment, but the Archive retrospective has unabashedly included several of them. It has also run the peculiar Passing Flickers (1982), a collection of comic and erotic scenes set in a film studio. Based on a column Li wrote for local newspapers, the film can’t be called good, but it does have fun revealing the bumbling and egotism of mass movie production.

For Hong Kong fans, it offers rare glimpses of the Shaw film factory’s work routines. We see Mitchell cameras, and we learn that the staff stored each actor’s period makeup and whiskers in a labeled box for quick access. We see the Hair Man fix coiffures, glue on beards, and occasionally manicure pubic regions. There’s also satire of local movie celebs, including a portrait of the sneaky independent producer Zhao (= Golden Harvest chief Raymond Chow?).

Tedious and mostly unfunny, Passing Flickers suggests that Li relaxed into an attitude of simply enjoying what he could get away with. Of his quickies, he remarked: “I made those film with my heart and soul. They may look like crap to you, but they’re gems to me.” Even in his hack days, Li remained a central figure in Hong Kong film.

(1) I take this information from Wong Ain-ling, ed. Li Han-hsiang, Storyteller (HK Film Archive, 2007), p. 214. My final Li quotation is from p. 166.

(2) The script for Kill Bill includes the instruction, “We do a quick Shaw Brothers zoom into her eyes.”

Lisa Lu in The Empress Dowager.

A many-splendored thing 9: On, and over, the edge

Films from the Fragrant Harbor

Sorry to be late with this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival. The last three days have been mighty busy, including a morning of roundtables with journalists and local critics, a supper with Mr and Mrs Johnnie To, an encounter with Ringo Lam, and other escapades. Plus heavy viewings of classics by Li Han-hsiang. I hope to blog about all this before I leave on Thursday. In the meantime, I’ll catch up on what any good festival is about…the films. Or rather, the ones I’ve liked most in the last few days.

Paolo Gioli has been making experimental films since the 1960s. From one angle, his approach converges with the work of filmmakers like Ken Jacobs and Ernie Gehr. Gioli employs optical printing and other techniques to halt, fragment, and superimpose images, many of them from found footage. Perforations flutter across the screen and framelines dance; single-frame montage imparts hallucinatory movement to a static picture; negative and positive images bounce off one another. The very concept of a shot or of a film frame dissolves in this lovely work.

But Gioli’s originality goes beyond the tradition of recasting found footage. Anticipating recent gallery artists who rig up their own movie machines, he films with pinhole cameras made of buttons or seashells, or uses leaves to create an extra shutter. The results can be aggressive or lyrical, and I found them completely fascinating. The first of four programs of his work was my first sight of Gioli’s work. How could I have missed it?

All the five films in the set, mostly from the late 1960s and early 1970s, were very impressive. In Traces of traces (1969), the abstract whorls and speckles are made from filmstock pressed upon his skin and fingertips. According to My Glass Eye (1971) assaults us with a flurry of Muybridge-like postures and fluttering close-ups, all to a threatening drumbeat.

My favorite was the gentler Anonimatograph (1972), recomposed from a 35mm home movie from the 1910s and 1920s. The shots settle into layers, and as they peel off we see people in different phases of their lives, sometimes studying each other across the years. Family portraits become eerie silhouettes and cameos. Even gouges on the emulsion serve as testimony to time gone.

Mark McElhatten, an expert on experimental film, provided the catalogue essay and an enlightening introduction to the screening, as well as an after-film discussion. He pointed out Gioli’s fascination with the textures of the human body as they are shaped by time and space, and then captured on the skin of film itself. Film as a tactile medium: No surprise that Gioli is also a sculptor.

You can read more about his work in Mark’s detailed essay for a Lincoln Center retrospective. This is Gioli’s suitably sparse website, and here is a site offering a DVD collection (unhappily not including Anonimatograph).

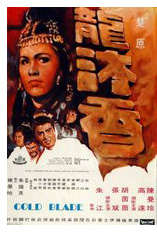

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade begins with a graceful title sequence showing our two heroes practicing their signature moves in slow motion and floating aerobatics. These maneuvers will of course prove important at the climax. The story was written for the screen, but it’s as full of twists and double-dealing as a martial-arts novel. The cutting is frantically fast (average shot length of 4.4 seconds!) but always intelligible. Chor Yuen provides his characteristically crammed fight scenes. His long lenses create layers of pulsing foreground movement that yield intermittent views of his protagonists. All in all, a satisfying reminder of the first golden era of Hong Kong action film.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Naturally, Bubble Fiction is filled with retro music, dances, fashions, and hair styles, with plenty of in-jokes about J-pop culture and references to its Hollywood source. “Don’t tell me you came in a DeLorean?” a skeptic asks our heroine. Bubble-era Japan is tellingly satirized, with profligate salarymen in loose suits lined up and waving banknotes to flag down cabs. The director painstakingly reconstructed the Tokyo of the time, including elaborate desserts and hand-punched train tickets.

Of course catastrophe is thwarted, and Mayumi comes back to a sunnier future, having gained a father and a new place in the community. Lighter than air, full of ingratiating gags, and cleverly crafted on Hollywood’s script model, Bubble Fiction proved just the sort of good-natured movie that I needed after 3 ¼ films earlier that day. Fragrant Harbor filmmaker Tsui Hark once wisely remarked: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

For credits and further info, check out the Pony Canyon site and Russell Edwards’ Variety review.

In the wake of Infernal Affairs, Hong Kong movies have been filled with undercover cops turning confused, bitter, and suicidal. On the Edge (2006) from the Herman Yau retrospective here at the festival, is one of the very best. Like Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive, this starts from a social fact: Most moles returning to duty don’t last more than a few years. Why? On the Edge explores the possibility that the friendships forged in the underworld are more authentic and durable than the stern bureaucracy of law and order.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

Thanks to a flashback structure, we see Nick’s rise in the gang juxtaposed to his slump once he’s back in uniform. Without being heavy-handed, the film juxtaposes a scene of Nick trying to return to civilian life with a parallel moment in his Triad days. It isn’t easy to advance two stories at once, but Yau manages it easily. There are also many sharp character bits, expressed—as customary in Hong Kong films—through confrontations and combats. A scene in nightclub builds tension as Ng and Wong, crook and cop, seize karaoke microphones to bark challenges to one another.

Without recourse to the flourishes of a certain Hollywood film on a similar theme, On the Edge exposes the anguish of a man cut adrift from the world that gave him his identity. Simple and modest, but with subtle touches (watch out for the disabled man on the handcart), Yau’s B-film aesthetic deals straightforwardly with plot, character, pungent locations, and a fine cast. You don’t need portentous symbols like a rat skittering along a condo railing. Just tell the story of one man who lost himself.

A many-splendored thing 8: The spice of life

Two more days at the Hong Kong film festival include…..

Seeing a lion dance auspiciously opening a new restaurant. I’d just eaten there last week, soon after it opened, with local filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei. The meal included pig-lung soup; good!

Watching the unexpectedly solid Wo Hu (2006). Wong Jing is widely known as the great vulgarian of Hong Kong cinema; nothing is too lowbrow to be tossed into his movies. I like some of his work, but I worried when the opening credits of a serious picture like this listed Wong as producer. Despite my concerns, this turned out to be a strong cops-and-triads pic. The presence of Eric Tsang, Francis Ng, and Jordan Chan helps a great deal, and Marco Mak’s direction is efficient enough. The real strength is the script, with a plot that is unusually taut for a Hong Kong movie.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

Wo Hu was much praised by local critics, and it seems to me the best of the recent crime films I’ve seen so far in the festival (Protégé, Undercover, Dog Bite Dog, and the surprisingly weak Confession of Pain). This is the one that could yield an interesting US remake. The title—get ready—translates as “Crouching Tiger.” The sequel, already announced, will be called Jia Lung: “Chasing Dragon.” The shamelessness of Hong Kong cinema isn’t dead quite yet.

Going on a rainy-day shopping circuit with Athena Tsui. Many of the old places supplying unusual and bootlegged DVDs have closed. Why? The government stepped up anti-piracy enforcement, and consumers can now get digital content online more easily. We did re-visit one place selling graymarket mainland versions of US, European, and Russian films, all for low prices (about US$3). Legit, I picked up mostly Japanese titles: Sabu’s Dead Run, the otaku hit Train Man, the Suo boxed set (didn’t have a DVD of Fancy Dance), and an unmissable item, The World Sinks, Except Japan. Go here for Twitchfilm’s coverage of the last-named.

The highlight was a trip to Comix Box in Sino Centre. It’s run by Neco Lo Che Ying, one of Hong Kong’s first independent animators, who started out in the 1970s. Neco was also the first to offer American superhero mags. Here he’s surrounded by some of his toys.

Thanks to Athena for the trip, the cocoanut-mango drink, and all the information about the HK film scene, including the factoids about Wo Hu.

Having dinner with Raymond Phathanavirangoon, who works for the energetic distribution company Fortissimo. Probably best known for handling Wong Kar-wai’s films, Fortissimo has established itself as one of the top distributors/ producers of ambitious international cinema (East Palace, West Palace, U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, Shortbus).

Among his other duties, Raymond makes presskits. This is seldom a creative endeavor, but Raymond’s results go far beyond the usual leaflet. He produces virtually museum-quality artifacts. His most flagrant kit promotes the Hungarian film Taxidermia, offering a marbled booklet in a shrink-wrapped styrofoam package.

Seeing James Yuen’s curious Heavenly Mission (2006). After several years in a Thai jail, young triad Ekin Chan wants to go straight. He asks an arms merchant to stake him to US$30 million, and he returns to Hong Kong to set up a vast charity. The cops don’t trust him, and neither do some of his old triad buddies. Problems ensue.

One of many crime movies screened in the Panorama section of the festival, this is neither the worst nor the best. The plot proceeds spasmodically, and our mysterious protagonist seems a little too passive. Nice to see Ti Lung again, though, playing an aging and pacific triad boss. Nice also to see for once Thailand treated not as hell but rather as purgatory, the place in which Ekin discovers spirituality and kindness. And, proving once more that there’s some little stab of pleasure in nearly every movie, we do get a nifty final shot.

Catching up with Soma films: Jouni Hokkanen, a regular at the HKIFF, gave me a sampler of several films he has made with another Finn, Simoujukka Ruippo. Their company is called Soma. You’ve probably heard of Soma’s most famous film, Pyongyang Robogirl (2001), which puts a traffic warden’s rigid moves to a techno beat.

Soma has made other films about North Korea, most ambitiously a survey of the nation’s cinema called The Dictator’s Cut (2005).

These entertaining and informative babies won’t be on YouTube. The Soma website is under construction, but it does give a list of the films, all of which would seem natural film festival choices.

Enjoying in an old-fashioned way Herman Yau’s Give Them a Chance (2003): The notion of a movie about how HK teenagers become breakdancing stars didn’t seem promising, but it turns out to be a sweet piece of work. Yau has always had sympathy for grassroots life here, and he makes his ensemble plausible and ingratiating.

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

Yau, a rocker himself, treats the clichés of the musical film with casual zest. Romantic rivalries flare up, health problems keep a promising dancer offstage, youthful energy collides with old-fashioned tastes, and corrupt promoters try to discourage naïve hopefuls. Of course there are lively dance numbers. In the process, alienated brothers come together and the kids’ efforts are crowned by their appeal to—who else?—the ordinary people of Hong Kong.

At a time when most HK directors seem wall-eyed for the Mainland box-office, here is a movie that is utterly local. It even has two English titles, Give Them a Chance and Give Me a Chance, just going to show that it wasn’t made for us Anglos. Actually, though, it speaks to anybody.

I’ll be blogging more about Yau’s work soon, since the festival is giving him a retrospective and a seminar. In the meantime, you can check his website.