Archive for the 'Directors: Tarr' Category

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

Just really long films

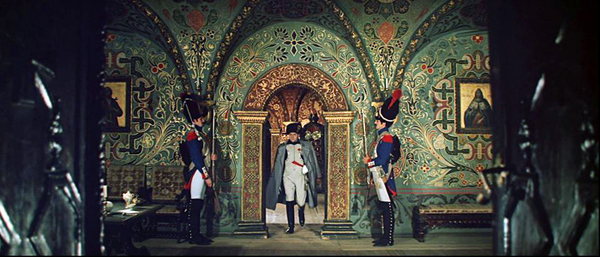

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

Nothing, if not critical

The Woman in the Window (1944).

O, gentle lady, do not put me to’t,/ For I am nothing, if not critical.

Iago, Othello

DB here:

Movie aficionados seem endlessly interested in film criticism—not just in what a writer says about a film, but in the very idea of criticism. I’ve suggested in a recent entry some of the historical reasons for this: the rise of the celebrity reviewer in the 1960s, the surge in interest in foreign and alternative cinemas, the emergence of filmic experiments, from Persona to Memento, that seemed to demand discussion.

With the internet, you can’t turn around without bumping into a film review. Aggregate sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic get tens of millions of hits a month. Of course many people are just checking on the range of opinions of a specific release, but I get a sense that many readers are more or less addicted to critical buzz as such. Connoisseurs of sentiment and snark, they still follow favorite reviewers just as we did in the 1960s, and they enjoy reading a critic they don’t agree with because she or he is an enticing writer.

In one corner of my workroom a steadily growing pile of books is no less a tribute to the flourishing of film criticism. Yes, books. I’m a committed Netizen (I’d better be, after three e-books, several web essays and videos, and over 610 blog entries). And for certain purposes, such as word search, I prefer digital versions of texts. But nothing beats a book for reading anywhere you happen to be, thumbing back to check a point, marking up margins with invective, and throwing across a room when you’ve decided the author is a dunce.

Here, though, are some books that won’t become missiles.

Revaluation

One consequence of the 1960s cult of the movie critic was a new genre of book—the anthology of a writer’s reviews, think pieces, and long-form essays, perhaps spiced by an interview or two. Call it a predecessor of a website if you must, but such books were tempting packages to cinephiles who wanted their fix in big gulps, not weekly doses. Then we eagerly read through Agee on Film, Dwight Macdonald on Movies, Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies, and many other collections. Some of these are now classics, most are forgotten, but the format still has life in it. Roger Ebert, exceptional in all respects, kept it going for years and crowned it with his Great Movies series. The format passed to academic presses like Wesleyan with Kent Jones’ Physical Evidence (2007) and Chicago with Dave Kehr’s When Movies Mattered (2011).

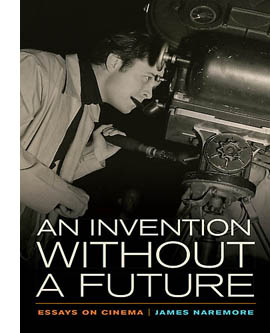

Like me, James Naremore is a creature of the 1960s, but with his typical discretion he has waited forty years to bring together a collection. Jim’s 1973 Filmguide to Psycho introduced me to his elegant thinking about movies. Since then he has written about a great many subjects, always with wit, steady vision, and deep and unostentatious learning. Now we have An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema (University of California Press).

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

The latter pieces were among Jim’s efforts at real-time film reviewing at Film Quarterly. Perhaps the sharpest edge of the book comes in the section housing them, called “In Defense of Criticism.” Jim, I think, considers criticism as, say, Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson considered it. Endowed with a tolerant, generous mind, the critic uses all the resources of culture—philosophical and moral ideas, social forces, artistic traditions—to illuminate the unique identity of the artwork.

More deeply, the critic expects the encounter with the artwork to challenge and change us. This to me is one difference between the reviewer and the critic. The reviewer expects the film to live up to his or her solidly entrenched point of view. The critic is open to being shaken, taught, and even transformed by the film. The reviewer projects confidence, the critic displays curiosity.

This ambitious conception of criticism is at risk today from two forces. There is the sheer blather of pop journalism and the Internet, which have pushed film culture from criticism to comments to chat to chatter. At the other end, some professors are allied against film as an art.

Today the humanities are in danger of losing their soul. Academic film studies has tended to focus on formal systems, industrial history, fandom, and identity politics—essential topics without which good criticism can’t be written, but topics that don’t engage directly with questions of art and artists.

Admitting that a certain detachment is valuable for research purposes, Naremore thinks that academics have become somewhat too clinical. Part of his book’s purpose is to draw their attention back to the intellectuals who flourished outside the academy, and for whom quality was worth arguing about.

I nevertheless think that evaluative criticism needs to be encouraged more, and I miss the days before the full-scale development of film studies, when film was made exciting and relevant by virtue of critical writing and debates over value.

So the last section consists of thoughtful essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, and Jonathan Rosenbaum—those who “had the greatest influence on the development of my taste.”

For my $.02, I’d just add that appraisals of quality shape a lot of academic writing, even in the Cult Studs vein. Showing that a film is racist or classist is surely an exercise in evaluation, employing moral or political criteria. Showing that fans of Twilight aren’t dumb no-hopers often springs from the researcher’s own esteem for the franchise. (Remember one of The Blog’s mottos: We are all nerds now.)

In effect, I think, Jim is pointing out that in a lot of film studies evaluation isn’t framed in specifically artistic terms. On that I’d certainly agree. Jim opens a new conversation by asking academics to look beyond their specializations and learn how the best arts journalists argue about quality. Seriously thought-through yet accessible to all, An Invention without a Future is a bracing, quietly subversive book.

Auteurs: From the ridiculous to the sublime

Jim would find signs of hope in two books dedicated to major directors.

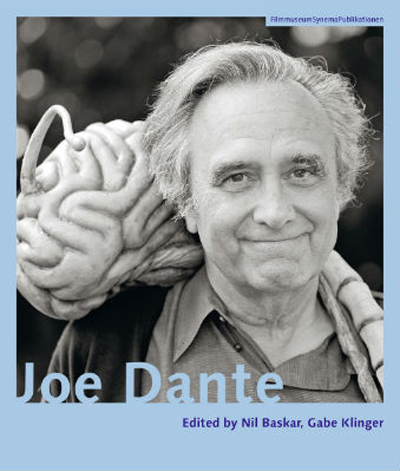

Nil Baskar and Gabe Klinger’s Joe Dante, a collection from the enterprising SYNEMA series at the Austrian Film Museum. Dante is just the sort of auteur that cinephiles prize. Working on the fringes of the system in despised genres, he’s a Movie Brat who loves B cinema, noir, and crazy comedy. This thick, square book contains virtually everything you’d ever want to know about the man who could be seen as Spielberg’s demented, funnier alter ego. Dante’s kiddie adventure stories and teen terror pix have celebrated and parodied Americans’ feverish love of war, big business, junk food, and lunatic media.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

Dante’s opposite number is Béla Tarr, whose films run the gamut from glum to morose, but they’re no less exhilarating. They find their ideal explication in András Bálint Kovács’ The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes. Kovács scrutinizes all the films, some little-known outside Hungary, and produces careful analyses that balance thematic interpretation with precise examinations of style. As a friend of Tarr’s, András is in a unique position to take us into this filmmaker’s grimy, splendid world.

Tarr, Kovács suggests, asks his audience to accept the illusions shaping the narrative world. Yet his structure and technique in the end yield a clearer view of the underlying forces than the characters can achieve—often, forces driven by conspiracy or betrayal. Accordingly, Tarr’s narratives tend to be cyclical, even when the story situation is unchanging, and his camera movements often trace a circular path. Many readers will particularly welcome Andras’ exciting account of Sátántangó, Tarr’s most demanding film. Based on a novel with an intricately circular structure, the film finds its own means to suggest a story swallowing its own tail. Most film books nowadays have pretty good frame illustrations, but these are well-sized to illustrate some of Tarr’s fine points of staging. In all, this book is likely the definitive study of Tarr’s art.

Museum pieces

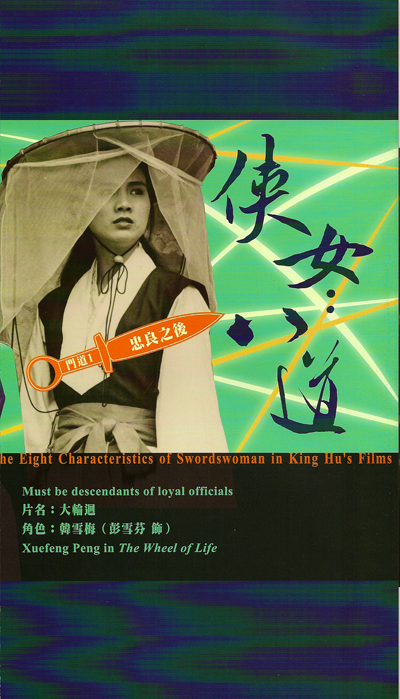

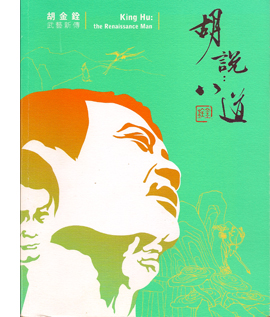

There’s another way to make the case for an auteur’s value: produce a dazzling book that pays tribute with gorgeous illustrations and informed critical commentary. This has been done by Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art in its catalogue King Hu: The Renaissance Man.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

Open the catalogue and you’re greeted by a large gatefold that sums up King Hu’s career. Thereafter, articles like Edmond Wong’s study of King Hu’s archetypes (derived from legend and theatre) supply the academic ballast, while images of the gallery displays fill up page after page. There are photo essays devoted to each of the films, as well as more gatefolds, illustrating themes such as “The Eight Characteristics of Inns in King Hu’s Films.” Just the hundred pages of King Hu documents—stills, portraits and self-portraits, along with caricatures of Bill Clinton and Princess Di—would be worth our attention. In all, this is the sort of museum show every cinephile dreams of visiting.

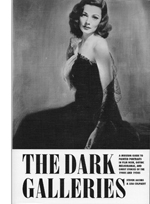

Art historian Steven Jacobs, author of The Wrong House, has collaborated with Lisa Colpaert to produce a dream of another sort. Their book invites you into an imaginary exhibition.

Visualize a museum containing all the paintings you find in films of the 1940s and 1950s. Now assume that some diligent scholar has sniffed out the provenance of all of them and provided stylistic and thematic commentary. And now assume that the research is presented as a guide to this virtual museum, using all the paraphernalia of art-historical commentary.

Confused? Here’s the opening of one entry:

[III.9] Portrait of Lady Caroline de Winter

(Unknown Artist, late 18th Century)

This full-length portrait represents Lady Caroline de Winter (1760-1808). The carefully rendered white dress, the column and curtains, and the vista of the landscape are unmistakably reminiscent of the portraits by Thomas Gainsborough, for instance his often-reproduced The Honourable Mrs. Graham (1775-1777). The landscape with trees probably stands for Manderley, the de Winter family estate on the Cornwall coast. For more than a century, the portrait was hanging in a long corridor in Manderley’s east wing, which was decorated with ancestral de Winter portraits. In the 1930s, the portrait played an important part in the life of one of Lady Caroline’s descendants, Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier). Maxim’s first wife Rebecca died in mysterious circumstances and once had a copy made of the white dress on the occasion of a masquerade ball at Manderley. . . .

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

A few years back at our summer film school, Steven impressed me when he identified the famously puzzling cubist still life in Suspicion as Picasso’s Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit (1931). The ultimate result of his and Lisa’s efforts is at once charming and deeply serious, enlightening us about a major motif in Hollywood’s “dark cinema.” It’s an extraordinary accomplishment, and an ideal gift for the patriarch, matriarch, exotic woman, or mystery man in your life.

Thanks to Lin Wenchi for giving me the King Hu catalogue. I’m unable to find an online source for this book, but when I do I will note it here. In the meantime, the sponsoring museum produced several videos for the exhibition. YouTube supplies a playlist of them. Our entries on this great director are here. I discuss his work in more detail in the books Planet Hong Kong and Poetics of Cinema.

For more exercises in creative criticism, visit Hilde D’haeyere’s website on silent comedy.

For more thoughts on film criticism on this blog, go here and here and here. A series on major American film critics of the 1940s starts here.

I record Joe Dante’s visit to Madison here and wrote about Béla Tarr’s films in these entries.

F for Fake (1972).

Good and good for you

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

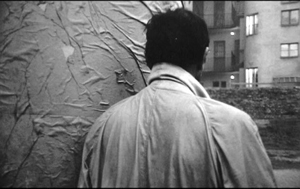

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.

My initial arguments about different registers of viewer perception and cognition were made in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). My case for Ozu is in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online. More recently, I’ve become interested in cinematic staging and have concentrated on challenging directors like Mizoguchi, Angelopoulos, and Hou; see On the History of Film Style (1998) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). All of these “slow” filmmakers ask us to be sensitive to unusual sorts of narrative patterning, and some purely non-narrative patterning. More thoughts on these matters can be found in The Way Hollywood Tells It (20006) and Poetics of Cinema (20007).

On this site, you can find similar lines of argument, especially about Béla Tarr, Mizoguchi Kenji, and silent directors like Louis Feuillade, Victor Sjöström and some Danish creators. See director entries for Hong Sangsoo, Liu Jiayin, and others mentioned above. Later this month I hope to post a bit more about how directors guide our attention without recourse to fast-paced editing–before editing was really invented.

Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994).

Splashy and spare, vengeance and regrets

DB here at the Hong Kong Film Festival:

Above, a tourist pic, the view from one of several escalators in the towering mall in Langham Place. Its flamboyance makes a sharp contrast with the movie I saw in the mall’s cinema, the minimalist Turin Horse. (See below.) The very end of this entry presents another view from the heights of Langham.

Righting wrongs, with new wrongs

Heaven’s Story.

Most Hong Kong thrillers and action pictures use revenge as their mainspring. It’s fairly uncommon, however, for a film to try to convey the cost that vengeance exacts on the avenger. Punished, directed by Law Wing-chong and produced by Johnnie To, makes an effort in this direction. A mogul’s spoiled daughter is kidnapped, and his refusal to bend to the captors’ will leads one, in a moment of pique, to kill her. After learning of her death, the mogul contracts with his chauffeur, a man who knows the underworld, to track down the gang.

The tycoon, played by Anthony Wong, goes through some agonizing as he must hide his daughter’s death from the girl’s stepmother. In turn, the chauffeur, Richie Jen (whose skilful performance dominates the movie), must abandon his son after executing the boss’s revenge. The men’s lives dissolve in their quest for payback, and the fact that the daughter, a brattish cocaine addict, is completely unsympathetic only makes the whole thing bleaker. An obvious parallel is the Eurothriller Taken, which presents a rash but innocent daughter rescued by a father who remorselessly cuts down everything in his path. Well-mounted, with perhaps too many flashbacks, Punished is that unusual Hong Kong film that insists that every effort to assuage male pride takes a toll in male pain as well.

But for a film that really investigates the cost of settling accounts you have to turn to Heaven’s Story. Here Zeze Takahisa, known mostly for erotic films, traces out the consequences of three killings. The cop Kaijima impulsively shoots a suspect. The locksmith Tomoki’s wife and child are brutally murdered by a teenager, Mitsuo. And elsewhere the little girl Sato is the only survivor of another family homicide.

The stories link up. Sato, in numb grief, sees Tomoki on television vowing to kill Mitsuo when he leaves prison. Because the man who killed her family has committed suicide, Sato embraces Tomoki’s reckless vendetta. She grows up hoping to help him kill Mitsuo. At the same time, Kaijima’s son develops a sidelong relation with her….

I really haven’t given away much, because the film traces these characters and several more across the space of—yes!—four and a half hours. As in a novel, the motives and connections among characters emerge slowly. Zeze’s plot maintains a balance between suspense about what comes next and curiosity about the past. And as in most network narratives, part of the pleasure is wondering how the new characters we meet will tie into the ramifying web of relationships.

Zeze splits the film into two “acts,” with intermission, at a bold spot: ending the first part on a pitch of suspense and starting the second with a new set of characters, making us wait for the developments set up at the end of act one. Working on a broad canvas allows the film to shift majestically, in large blocks, from one person to another. The same goes for the ending: After the main drama is resolved, Zeze allows a long epilogue in which many of the film’s motifs are gently set to rest.

That drama and those motifs, unsurprisingly, bear on the power of unspeakable acts to ignite our desire for revenge. Every character, even those unaware of the savage deaths in the past, is altered by the central killings. An amateur rock singer, a young woman almost defiantly self-centered, becomes a devoted mother, which seems to yield some hope; but her family is eventually shattered by echoes of Mitsuo’s crime.

Those more directly affected by the killings face more severe tests. Kaijima, for instance, tries to compensate for his impulsive shooting by giving monthly money to the victim’s wife and daughter. (The irony is that the money comes from his sideline, moonlighting as a paid killer.) The daughter grows up expecting Kaijima’s payments as her due and tries to extract more money from him, as if he were her surrogate father. This daughter, along with Mitsuo the teen murderer and the older woman who takes him in, come to unexpected prominence as the film unwinds a tale of sorry lives and compromised choices.

Mostly shot in rough-edged, somewhat bumpy shots, Heaven’s Story at first made me fret: 278 minutes of this? I needn’t have worried. The pace is steady, even relentless, but I didn’t find it monotonous, and a more polished presentation might have lacked the distressed urgency of what we get. Incidentally, the framing bits, showing a sinister puppet play with Shinto overtones, are filmed with smooth care. The contrasts in technique suggest that a more serene supernatural domain exists alongside the anxious sphere of human desires, where people persist in trying to redress old sins by committing new ones.

The obscurity of the everyday

A horse is feverishly hauling a cart, the camera riding low underneath the beast’s plunging head. The wheezing repetitive score rises to a scraping whine, then it’s replaced by the sound of fiercely whipping wind. The old driver pulls the cart up at a farmhouse, where he’s met wordlessly by a younger woman. As the wind tears at them, they take the horse to the barn, the cracked leather harness left on the cart. Inside the cottage, the woman helps the man change his clothes. The woman boils a pair of potatoes. She says: “It’s ready.” It’s the first line of dialogue, and it comes nineteen minutes into the film.

Thus begins the festival film that has exhilarated me most so far, The Turin Horse. With this movie, Béla Tarr, a favorite of mine (especially here, but also here and here), has given us his most spare entry yet. Almost nothing dramatic happens during its 140 minutes, and what does take place is opaque and enigmatic. The film refuses traditional exposition, forcing us to observe bits of behavior and speculate on why things unfold this way.

At one level, it’s the heritage of Neorealism paying off. In Umberto D’s scene of the housemaid preparing breakfast, we had an early example of sheer dailiness used to characterize a person and a milieu, as well as to absorb us in what we might call mundane beauty. But something different, more abstract and disturbing, happens when a film is nearly all routine. In the farmhouse, the old man and his daughter eat their steaming potatoes barehanded, squeezing and mushing them. He wraps himself in a blanket and stares out the window while she does household chores. Next day they arise, dress, and hurl themselves again into the blasting wind. (The wind ripping along the wet streets in Sátántangó is nothing compared to this gale.) In all, cramped settings observed with Tarr’s usual tactile detail, rendered gorgeous in black and white, become as obscurely allegorical as the magical tabletop in Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Other characters show up eventually. An hour in, a talkative friend arrives and provides a monologue cursing the ignoble forces that have driven intelligence from the world. Later some travelers appear outside at the well, with malevolent results. And the horse refuses to be fed. Perhaps at bottom the “story arc” is that light simply goes out of this world. Having dwelt on gestures (hands pouring out alcohol or struggling to harness the horse) and textures (the ripples of woodgrain on the stable door), the film slides into darkness. The motif is announced in the cryptic trailer for the movie.

From Tarr’s comments we learn that the man is a carter and the woman is his daughter. The film’s voice-over prologue invokes an episode from the life of Nietzsche, who once tried to stop a driver from mercilessly whipping his horse. The incident purportedly led to Nietzsche’s descent into insanity. Tarr has said that the film, based on a short story by László Krasznahorkai (who also wrote the novel Sátántangó), tries to imagine what happened to the horse after the incident.

Yet the horse is less important in the film than the carter and his daughter. It’s not hard to see them living a post-Nietzschean world, and the visitor’s rant about universal debasement may offer support for this interpretation. It’s another exercise in what an earlier entry called Tarr’s “postlude” vein, presenting what remains of life after history has more or less ended. Yet these are no stick figures in a metaphysical meditation. Virtually without psychology, father and daughter are defined through their sheer physical weight and movements. They confront the blasted landscape when they pass outside and the wind tears at them, but once inside they shift to the window to watch. The image of an observer trying to understand a harsh, senseless world beyond the walls is one we’ve seen in the opening of Perdition, and in the scene in which the obese doctor in Sátántangó planted at his desk tries to write down everything he sees happening outside.

Not that the cottage is any more welcoming. Splendidly filmed from a constrained variety of angles, the cottage seems bare of love, meaning, and what we normally consider drama. Tarr’s camera movements and the solemn rhythms of his shots (I counted only 37, including intertitles) are coordinated with the pace of the characters. Perhaps not since Dreyer’s Ordet has the lumbering pace of country life, the trudging gaits and reluctant effort to rise after sleeping, been rendered so expressively. Here, however, nothing is touched by grace

Tarr makes his inhospitable world spellbinding. I’m ready to watch the The Turin Horse again, even, or especially, if it proves to be Tarr’s last film.

For a detailed, less sympathetic review of Heaven’s Story, see Peter Debruge’s piece in Variety. Suggesting that The Turin Horse will be his final film, Béla Tarr discusses it here. At The MUBI Notebook, David Hudson has provided very informative coverage of the controversy around Tarr’s place in Hungarian cultural politics. For an interview with Tarr’s cinematographer, as well as a sensitive appreciation of the film, see Robert Koehler’s piece in the new Cinema Scope.

A view from Langham Place shopping mall, Mongkok.