Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

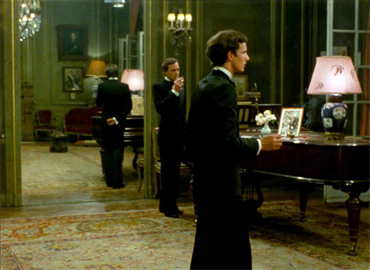

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

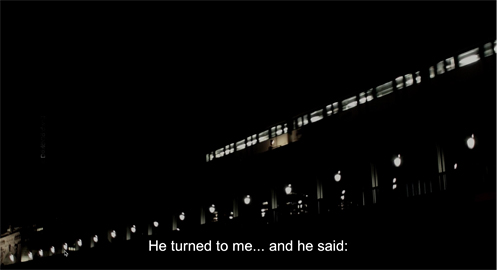

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

Rotterdam surprises

Mitra (2021)

Kristin here:

On Saturday morning (8:30 am our time), the International Film Festival Rotterdam will be screening its annual Surprise Film. We’re naturally curious to learn what it is. But Rotterdam comes so early in the year that often we go into its other offerings knowing almost nothing about them. Here are two of the very pleasant surprises from recent days.

Iranian cinema from the Netherlands

Kaweh Modiri, the director of Mitra, was born in Iran but has lived in the Netherlands since he was six years old. Still, he remains concerned with Iranian issues and clearly has been influenced by the flourishing Iranian art cinema of recent decades.

Asghar Farhadi’s success in international festivals and territories has been the most influential instance recently, at least outside of Iran. His plots are often built around conflicts, not between good and bad people, but behind people who clash because of cross-purposes. Late revelations and tortured discussions lead to reconciliations that are not the happy endings of Hollywood films but instead are resigned agreements to admit mistakes and make compromises.

Mitra is such a film, but it is based around more politically based conflicts than Farhadi has used–ones that have life and death consequences for those involved.

The film moves between two settings and eras: Tehran in 1981-82, the years shortly after the ouster of the Shah, and the Netherlands in 2019, the fortieth anniversary of that revolution. The opening is set in 1982, when the heroine, Haleh, receives an abrupt, unexpected telephone calls announcing that her daughter Mitra has been executed. We move then to 2019, when Haleh, now an academic in the Netherlands, addresses a conference on “The Islamic Revolution at Forty.” Soon she is visited by members of “The Organization,” a group aimed at bringing down the current government of Iran. They tell Haleh that Leyla, whose betrayal of Mitra caused her death, has arrived with her daughter in the Netherlands. She goes under the name Sale, having appealed for refuge status. The Organization wants Haleh’s confirmation that Sale is indeed Leyla.

The rest of the plot centers around a shifting relationship, as Haleh vows revenge on Leyla. Her goal is complicated by the fact that she has never actually seen Leyla, having only heard her voice. Nevertheless, she calls Sale and is convinced that she recognizes the woman’s voice, even after nearly forty years. Once they meet, however, Haleh seemingly bonds with Sale and her endearing daughter Nilu. Indeed, Haleh’s attraction to Nilu hints at her possible acceptance of Sale as a substitute daughter and Nilu as a granddaughter.

Interspersed with this story are flashbacks to the younger Haleh’s 1981 experiences, when Mitra, who has joined the resistance in Iran, is still alive. Scenes like a clandestine meeting with Mitra at a crowded market emphasize Haleh’s love for her daughter (top of section).

Modiri expertly lures us into sympathizing with all the characters involved. To the end we remain uncertain as to whether Sale, who after some doubts accepts Haleh as a friend and even as a substitute mother in a new land, is actually the treacherous Leyla. Even if she is, is it worth ruining young Nilu’s life to turn Sale in to the ruthless Organization?

Supporting all this is Haleh’s relationship with her brother Mohsen, who at first seems a somewhat comic, eccentric sidekick but is later revealed to be suffering the effects of torture and lengthy imprisonment in Iran. His exchanges with Haleh initially seem like sibling bickering, but he becomes the moral compass that holds her together as she pursues revenge (see top).

Mitra starts out seeming to be a conventional revenge story, but its moral and personal shifts and surprises lead to a moving and not-quite-resolved ending.

The film has had its world premiere at the IFFR and is due for a May 20 release in the Netherlands. I hope it plays other festivals and travels further, because it is a definite contribution to the continuation of world interest in Iranian cinema. Like other such Iranian films, it had to be made elsewhere (the scenes set in Iran were shot in Jordan), but it carries forward what we have loved about Iranian films.

An Australian surveillance-cam thriller

Jonathan Ogilvie’s Lone Wolf (2021) adopts the new convention of creating a story based largely on surveillance and cell-phone footage. In a frame story Kylie, a Special Crimes Sergeant, bursts into the office of an unnamed Police Commissioner and demands that he watch a video she has secretly compiled from a mass of such footage.

The inner story is seemingly set more-or-less in the present day, but it’s a slightly alternative world in which surveillance has become even more pervasive than it already is. The read-outs in the images reveal that cameras are spying on the characters from such household devices as TVs and smoke detectors. One of these is, ironically, in a bathroom where Winnie sneaks the occasional cigarette by an open window (above). How Kylie gets access to all of these is never explained, and the premise is implausible–especially in scenes built around extensive, undamaged footage which she has somehow managed to extract from a phone that has been through a bomb explosion.

If one stifles such doubts, however, the tale Kylie’s film tells is an absorbing one, full of twists and turns. It centers on Conrad and Winnie, a couple who run a book/video-rental/sex shop and do occasional jobs for underground political groups. They are not the most appealing characters, but they gain our sympathy through their devotion to Winnie’s charming little brother Stevie, who has Down’s Syndrome and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

Australia is soon to host a G20 meeting, and a man from a radical group asks Conrad to set up a “victimless atrocity” in the form of a bomb explosion in a deserted area. At first Conrad refuses, but when offered a large sum, he gives in. Despite the grimness of this plot thread, there is quite a bit of humor in the film, provided by Stevie and by a group of Conrad’s misfit friends who gather to play cards above the shop. The combination of found footage also creates occasionally amusing moments, as when the film-within-a-film includes an instructional YouTube-style video that Stevie has posted or poor-quality footage from an old security camera in the shop that Winnie and Conrad think has been turned off (bottom).

The consequences of the bomb plot introduce a grim twist, but the return to the frame story creates a more gratifying one as Kylie reveals why she has pressed her video upon the Commissioner.

While Rotterdam provided Lone Wolf‘s world premiere, it has a distributor in Australia, though its August, 2020 release was postponed by the pandemic. Ogilvie hopes it will have wide theatrical play after a possible in-person premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival this coming August.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to discover these surprises!

Lone Wolf (2021)

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

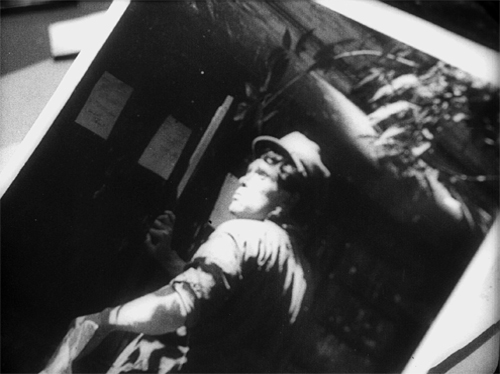

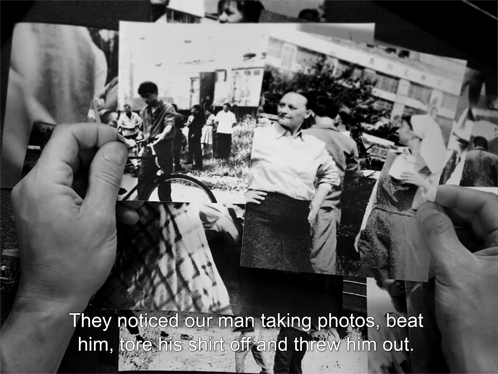

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

When media become manageable: Streaming, film research, and the Celestial Multiplex

Never coming to the Celestial Multiplex: Liberty Belles (Del Henderson, 1916).

DB here:

A directors’ roundtable in The Hollywood Reporter says a lot in a little.

Fernando Meirelles: This June, The Two Popes was in 35 festivals. Then we were going to have two or three weeks of theaters. And then the [Netflix] platform. I mean, it couldn’t be better.

Martin Scorsese: We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

Meirelles casually omits DVDs, at one point the most rapidly adopted format of consumer media. Yeah, what ever happened to discs? And in what follows, I’ll take issue with Scorsese’s claim that streaming has triggered a revolution. It’s more a case of evolution that issued in a sweeping change, like Engels’ transformation of quantity into quality, or Hemingway’s claim that he went broke slowly, then quickly.

More important, I’ll try to assess the impact streaming has had on what Kristin and I and other researchers and teachers try to do–study film as an art form in its historical dimensions.

Managing your time, and your movies

If we’re looking for a revolutionary turning point, I’d suggest the moment that movies no longer became appointment viewing. When they played theaters you had limited access. The film was there for only a while (even The Sound of Music eventually left) and you had to watch it at specified times. On broadcast TV and cable, the same conditions applied. But with the arrival of consumer home videotape in the 1970s, the viewer was given greater control.

Akio Morita of Sony called it “time-shifting.” The phrase, shrewdly positioned as a defense of off-air copying, captures a fundamental appeal of physical media. You could watch a film at home, and whenever you wanted to. Yes, VHS and even Beta yielded shabby images and even worse sound, but (a) theatres were often not much better, and (b) a video rental was cheaper than a movie ticket. Most important was a general rule of media technology: For the mass market, convenience trumps quality.

Videotape swept the world in the 1980s and gave films an aftermarket. Many an indie filmmaker could get financing for a project on anticipated tape sales. The laserdisc gained some attention in the 1990s, becoming a sort of transitional format. It improved quality (better analog picture, digital sound) but had drawbacks too. A movie wouldn’t fit on a single disc side, and a laserdisc was pricier than tape. LD remained a niche format, chiefly for educators and home-theatre enthusiasts.

The laserdisc was superseded by the DVD, introduced in 1996. Journalists claimed that it enjoyed the fastest consumer takeup in electronics history. Discs were more convenient than tapes, and proof of concept had been provided by the success of CDs for music. To compete, cable companies introduced “video on demand,” a time-shifting compromise between scheduled cable delivery and rental of tape or disc. People still use cable VOD, and for some purposes it’s a cheaper alternative to committing to subscription services.

Reviewing The Irishman, a critic suggested that most people will skip seeing it in theatres and watch it on Netflix, where it’s “more manageable.” With tape and disc, either analog or digital, consumers became accustomed to a huge degree of manageability. They could pause, skip ahead or skip back, race fast-forward or –back, play slowly, and above all play the movie over and over. DVDs made all these options quicker and more convenient than tape had. The market boomed. Video stores made discs available for rental, as tapes had been, and retail stores offered them for sale, at increasingly low prices.

But there were problems. In the 2000s there was a glut of DVDs, and consumers began to realize that a few weeks after release many titles would end up in the bargain racks. A brisk secondary market developed thanks to the US “first sale” doctrine, most virtuosically exploited by Redbox. Worse, there was piracy. Pirating analog tapes degraded quality across generations, but with digital discs you could rip perfect clones. Any teenager could hack past region coding and anticopying software.

The Blu-ray disc was an improvement on the first-generation DVDs, and it came along as more people were buying widescreen and high-definition home monitors. Properly mastered, Blu-ray discs looked good, and they had bigger storage capacity. Some consumers got excited, but the improved format couldn’t arrest the headlong decline of disc sales. In addition, the industry’s rationale for Blu-ray was its resistance to rippng, but hackers breached the codes with ludicrous speed.

From this angle, streaming is parallel to digital theatre projection : a new phase in the war against piracy. Likewise, as in theatrical screenings, you’re paying for an experience, not an item. You’re not buying an object you can copy or resell. If a movie is available only on streaming, you’re renting something, not owning it legally. One aspect of manageability—personally possessing a movie—is traded away for convenience and, ultimately, for limited access, as I’ll try to show.

Not so gently down the stream

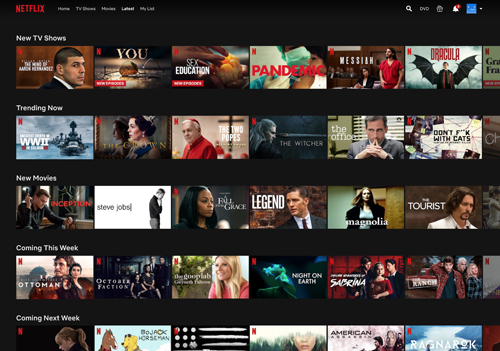

With streaming, the age of appointment viewing seems more or less over. And the infinite vista of the Internet has encouraged tech-heads to imagine something like the Celestial Jukebox, a vast virtual multiplex in which all movies will be available. If iTunes and Spotify did something like this for music, why not cinema?

Let’s consider the pluses and minuses of streaming for ordinary consumers and for filmmakers.

Obviously, there’s convenience. After the monstrous tape cassettes, DVDs looked adorably slim. Now, gathering in slippery stacks, they have their own sinister aura. With streaming, there’s no need to run out to the video store or to buy new shelving to support a bulging library of discs.

There’s also price, compared to either theater tickets or cable fees. From $6.99 per month (Disney+) to $12.99 (Netflix), streaming services promise to provide TV and movies quite cheaply. And there’s the range of choice, which even on second-tier streamers exceeds the capacity of most towns’ video stores back in the day. Finally, there are many obscure films lurking in the corners of most streamers, so the joy of discovery is still there to a degree.

On the minus side, there’s one that gets the most press—the further erosion of “the theatrical experience.” Critics emphasize the pleasures that come from being in an audience, but this always seems to me overrated. More valuable to me are the scale of image and sound you get in a theatre. I like my movies to loom.

Above all, there’s a virtue in the lack of manageability. In the theatre you can’t pause the movie or run back or skip ahead. You can close your eyes, look away, or leave, but at bottom you’re there to turn your sensorium over to the filmmaker, to go through an experience you don’t control. This unshakeable grip on your attention yields some of cinema’s most powerful effects.

The condition of privatized viewing isn’t unique to streaming, of course. Nor is another drawback, that of the cyclical expiration and refreshing of “content” on streaming platforms. Admittedly, we’re warned. Newspapers and websites run alerts notifying us when a title is leaving a service—perhaps for a little while, perhaps longer, perhaps forever. And this situation is a bit like DVDs’ going out of print. But at least some disc copies exist to be sold second-hand or cloned as files. In working on my book on the 1940s, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I could track down arcane titles on out-of-print discs, and at fair prices. When something not on disc leaves streaming, how do you access it?

I think there will be some pushback when subscribers learn about the costs that more and more services are tacking on. Yes, with Amazon Prime for $119 per year you get access to many films, along with other services. But for a great many films Amazon demands an extra rental fee and very short-term access. Within Amazon, there are channels (Britbox, HBO Now, Starz, Cinemax et al.), all of which demand further subscription payments. As people start to realize that streamers will have exclusive licenses for titles, they’ll feel pressure to subscribe to many services. Here, as elsewhere, the total streaming price tag starts to look like cable fees. Even the New York Times has noticed.

Another problem won’t bother most consumers, but it does matter. A streamed title will occasionally be in an incorrect aspect ratio. Most commonly, a Scope (2.39 or so) image will be cropped to 1.85. I noted this some years back, relying on a website showing faulty Netflix transfers, but that site seems to have been taken over by … Netflix itself.

Netflix will say, with all “content providers,” that they get the best material they can from their licensors. I don’t watch streaming enough to know how common wrong aspect ratios are, but if you know of examples, I’d like to hear.

Finally, even streaming companies can collapse. Unless Apple buys a studio (Lionsgate? MGM? Columbia?), it must rely on original content, and it could well flop. On the day I’m writing this, one hedge fund manager predicts we have reached peak Netflix. Given greater competition, slower growth, and accelerating cancellations, he maintains that Netflix is on the wane. If it scales back or fails (it currently carries $12.43 billion in debt), what will happen to its licensed material and its original content?

What about creators? Filmmakers, especially screenwriters, have enjoyed boom times. It may be a bubble, with over 500 scripted series available on broadcast, cable, and streaming. Still, it has given everyone a lot of opportunities. Documentary filmmaking in particular has enjoyed a shot in the arm.

And features are still doing quite well, at least on Netflix. Of the streamer’s top 10 releases in 2019, seven were features. But those proportions may change. Aside from big theatrical movies licensed from the studios, the impact of proprietary “event” programming (War Machine, Bird Box) has been fairly ephemeral. (Obviously Roma and The Irishman are exceptions.) The strength of streaming, it seems to me, is the same thing that sustained broadcast TV: serial narratives. Hence the popularity of Friends and The Office, as well as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black.

Like network TV, a streamer needs a reliable, constant flow of content—not only many shows, but many episodes. The model of the series, if only in six or eight parts, secures the loyalty of the viewer for the long term. Even if all episodes are dumped at once, the promise of continuation after an interval of a year or several months keeps the viewer willing to hang on till the next season.

The pressure on the creators is predictable. Since form follows format, writers and producers will be pushed to come up with series ideas. A friend of mine pitched a feature-length movie to a streaming service. The suits loved the idea but wanted it as a series and were already scanning the script outline for a plot point that could launch a second season. Some of the streaming series I’ve seen, notably Errol Morris’s Wormwood, seemed to me stretched.

If a filmmaker lands a feature film on a streaming platform, other problems could follow. We’re well aware that independent filmmakers gain few royalties from streaming; their big check tends to be the initial acquisition. At the same time, they can’t be sure that people are watching their entire movie. My barber couldn’t stick with The Irishman, even with pee breaks.

Streamers seem to have accepted grazing as basic to the viewing experience. For purposes of measuring total viewership, Netflix counts a “viewing” of a film or program as a minimum of two minutes. In the light of the two-minute rule, we might expect filmmakers to crowd their opening scenes with plenty to grab us. That goes back to TV and TV-influenced films, of course, which tried to have a strong teaser even before the credits. Now, it turns out, streaming pop songs are being crafted with shorter intros and earlier choruses “to get to the good stuff sooner.” Maybe filmmakers will be trying the same thing. Maybe they already are.

Streaming and film research

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018).

Finally, what are some consequences of streaming for researchers, educators, and your all-around obsessive cinephile?

I think it’s fair to say that home video, in the form of tape, laserdisc, and digital disc, democratized film study. From the late 1960s on, I traveled to archives and film distributors to watch films for my research. It was troublesome, time-consuming, and costly. As a grad student I took a bus from Iowa City to Chicago to watch 16mm prints of Dreyer and Sontag films. I drove to Eastman House to see films in projection. I stayed in Paris a couple of months to work at the Cinémathèque Française on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse.

As a prof here at Madison I spent hundreds of hours watching prints in our Center for Film and Theater Research. Over the decades I trekked to Denmark for Dreyer and 1910s films, to Japan for silent films, to Paris and Munich and the BFI and MoMA and UCLA and Eastman House and the Library of Congress, and above all Brussels for many, many projects. Collectors, from Manhattan, Tokyo, and Milwaukee helped as well. Kristin and I owe archivists everything.

The terrible quality of films on tape didn’t help me study visual style, but laserdiscs were a big improvement. (Hong Kong films tended not to be in Scope on tape but were on LD.) And one LD format, CAV, was frame-accurate; you could study a shot frame by frame, something not possible with many DVDs. There’s always a trade-off with any technology.

Even after even after DVDs arrived I kept up my travels. I could use discs for bulk background viewing, but often I still had to rely on prints. Sometimes I wanted to count frames (handy in looking at Soviet montage and Hong Kong action). Moreover, looking at film prints revealed that the color palettes on DVDs could be quite different, and soundtracks were often cleaned up for the home market. And of course thousands of films, especially from outside Hollywood or in the first decades of cinema, were never going to be available on consumer video. My most recent extended archive stay, in Washington in 2017 thanks to a Kluge Professorship, showed me the glories of the 1910s in prints that are mostly accessible only to researchers.

What do scholars of an analytical bent need? Entire films that can be paused. Frame stills, made photographically or through software. Clips as evidence for our claims. Stills and clips are our equivalents to quotation for literary scholars and illustrations for art historians.

Apart from convenience and cost savings, the disc revolution yielded something I couldn’t get otherwise. In an archive, it’s impossible to study film-based 3D cinema. But thanks to Blu-ray, I can stop on a 3D frame. (. . . And, for instance, spot the way Hitchcock makes the clock quietly pop out in Dial M for Murder, below). This is a unique benefit—but a waning one, as 3D discs are increasingly hard to find and 3D monitors scarcely exist any more. As I said, trade-offs.

From this standpoint, Netflix and its counterparts offer a step down from DVD and Blu-ray. In terms of choice, many films aren’t currently available on streaming, and many more never will be. You can pull a DVD off a shelf whether you’re online or not, but for streaming you need a good connection. The controls of a streaming view aren’t as precise as those on a DVD player; slow forward and back to study cuts and gestures aren’t feasible, it seems.

When cable cropped films, as it frequently did, you had recourse to DVDs, perhaps even from foreign sources. But as exclusive licensing increases, only one service will have a title. Frame grabs are possible with some software, but clips are more difficult.

Worst of all, many worthwhile films will apparently never find their way to disc. I first noticed this in 2017 when I wanted to buy a copy of I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, a Netflix release of a Sundance title. As far as I can tell, it’s not available on DVD. The same fate has befallen one of my favorite films of 2018, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only a few years ago it would be unthinkable for a Coen Brothers film not to find DVD release. Even Roma has had to wait for a Criterion deal to make it to disc. Clearly Netflix, and perhaps other streamers, believe that putting films on disc damages the business plan. So Meirelles doesn’t include DVDs in the lifespan of The Two Popes.

Without DVDs, some cinephiliac consumers are lamenting, rightly, the loss of bonus materials. The Criterion Channel has been exceptionally generous in shifting over its supplements to the streaming platform, but other companies haven’t been. Scholars and teachers rely on the best bonus items, including filmmaker commentaries, to give students behind-the scenes information on the creative process. There are, I understand, rights issues around supplements, and bandwidth is at a premium, but there’s no point in pretending that the loss of disc versions hasn’t been important.

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas put forth the question debated in the directors’ roundtable I mentioned: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

Still, the big changeover hasn’t happened quite yet. Every year has its failed blockbusters, and films big and middling and little (Blumhouse, for instance) still continue. Arthouse theatres, which rely on midrange items, indie production, and foreign fare, are putting up a vigorous fight, emphasizing live events and community engagement.

Meanwhile, streaming makes film festivals and film archives more important. Festivals may host the few plays that a movie gets (as in the 35 fests which ran The Two Popes), and filmmakers, as Kent Jones remarks, are eager for their films to play on the big screen in those venues. Archives will need not only to preserve films but also make classics and current movies available in theatrical circumstances. Smart film clubs like the Chicago Film Society and our Cinematheque keep film-based screenings alive.

Before home video, few film scholars undertook the scrutiny of form and style. Those who did had to use editing machines like these. (One scholar called my study of Dreyer, not admiringly, the first Steenbeck book.) Ironically, just as an avalanche of films became available for academic study, and as tools for studying them closely became available for everyone, most researchers turned away from cinema’s aesthetic history and a film’s specific design in order to interpret their cultural contexts. There were exceptions, like Yuri Tsivian’s efforts to systematically study patterns of shot length, but they were rare.

Whatever the value of cultural critique, one result was to leave aesthetic film analysis largely to cinephiles and fans. Thankfully, the emergence of the visual essay, in the hands of tech-savvy filmmakers like kogonada and Tony Zhao and Taylor Ramos, eventually attracted academic attention. Film analysis has returned in the vehicle of the video essay, which is a stimulating, teaching-friendly format. Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have participated in this trend through our work with Criterion and occasional video lectures linked to this site.

All this was made possible through the digital revolution, or evolution, and we should be grateful. Still, streaming filters out a lot of what we want to study. It’s clear that, for all their shortcomings, physical media were our best compromise for keeping alive the heritage of critical and historical analysis of cinema. We’ve largely lost physical motion pictures as a contemporary medium. (How many young scholars, or filmmakers for that matter, have handled a 35mm print?) Now, to lose DVDs and Blu-rays is to lose precious opportunities to understand how films work and work on us.

Thanks to all the archivists, collectors, and fellow researchers who made our research so fruitful and enjoyable in the pre-digital age.

A good overview of the streaming business at this point is “The future of entertainment,” in The Economist.

Kristin discusses the fantasy of the Celestial Multiplex with archivists Schawn Belston and Mike Pogorzelski. For examples of how to watch a film on film slowly, go here. Samples of editing-table discoveries are here and especially in the Library of Congress series that starts here. In another entry, I discuss the use of 3D in Dial M for Murder.

P.S. 24 January 2020: Then there’s this, from Facebook.

Dial M for Murder (1954).