Ratio-cination

Sunday | December 19, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt.

DB here:

Good timing. Just as I was about to enable more aspect-ratio fetishism, I got news of the publication of Widescreen Worldwide, from John Libbey. Edited by John Belton, Sheldon Hall, and Steve Neale, it has its distant origins in a 2003 conference at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. Widescreen Worldwide will be a very useful volume, with material on little-studied U. S. systems and a lot of information on formats in Japan, France, Italy, and Russia, even Norway.  Most studies of widescreen technology seldom discuss the creative uses to which it was put. But this collection features several essays focusing on the artistry of the wide formats, emphasizing the work of Preminger, Peckinpah, Okamoto, Suzuki, et al. As the publisher’s blurb puts it:

Most studies of widescreen technology seldom discuss the creative uses to which it was put. But this collection features several essays focusing on the artistry of the wide formats, emphasizing the work of Preminger, Peckinpah, Okamoto, Suzuki, et al. As the publisher’s blurb puts it:

The book documents how the aesthetic strategies explored during the first wave of American widescreen films underwent revision in Europe and Asia as filmmakers brought their own idiolect to the language of widescreen mise-en-scène, editing, and sound practices. As a global phenomenon, widescreen cinema thus presents the opportunity to examine how different cultures appropriate the technology to advance extremely different cultural and aesthetic agendas.

I have an essay included on the Shaw Brothers directors, and I’m happy to be in such distinguished company in this major publication. My essay is available on this site. The paper I gave at the conference, on Hou Hsiao-hsien’s early anamorphic films, is also posted here.

Speaking of widescreen: Today, we go back to While the City Sleeps and SuperScope, thanks to some correspondents and further fooling around on my part.

Ratio decidendi

The story so far: SuperScope was a widescreen system devised by Irving and Joseph Tushinsky for RKO . It extracted a wide image from the 1.37 standard frame and printed it as a squeezed anamorphic frame, to be unsqueezed at a ratio of 2.0 to 1. (A later version allowed for a 2.35 stretch.) In principle, it’s an early version of what Super 35 does now. Some RKO films, notably Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), were shot in knowledge that they would be given the SuperScope treatment; others were SuperScoped after the fact.

The question before the jury was: Do SuperScope prints of Lang’s While the City Sleep (1956) faithfully reflect his intentions? The answer I settled on was: Probably not. A Variety story indicated that the SuperScope prints were made for European distribution, though perhaps some sneaked into the US theatrical market or the 16mm aftermarket.

Now for a little more on Lang’s compositions. Several viewers have commented on all the headroom visible in the full frame. The ‘Scope print I examined displayed some as well, but not as much, as my illustrations for the earlier entry indicate. More likely the film was masked in the US to something like 1.66 or 1.75. I reproduced some frames from a 1.75 laserdisc version, and they look reasonably good. Overall, I suggested that City’s fairly open compositions suggest that Lang was expecting the film to be masked somewhat in projection, but not to the full 2.0:1 ratio we get with SuperScope.

Although for most of its length, While the City Sleeps seems quite okay at 2.0, I found one shot that would be quite awkward in full SuperScope. Alas, I didn’t photograph it from the 35mm European print I examined, but I’ve used my stills from the print to guide my cropping of the 1.37 frame in this instance. The results are, as the lawyers say, probative.

The scene is mundane: Walter Kyle gets a phone call from his errant wife Dorothy. She’s carrying on an affair with Harry, the art director of the newspaper Walter runs. Walter talks with her, and Lang cuts to her responding. I show you the 1.75 versions.

When Lang cuts back to Walter, he provides a new camera setup featuring the butler Steven. This is to prepare us for a joke: Walter says he’ll have Steven meet Dorothy at the front door in his underwear. Steven reacts with embarrassment. Given that a lot of the film plays on the sexual rapacity of men, the humor is a shade sick.

A narrative convention: The stuffy, puritanical butler. But notice that in the 1.75 frame, Steven’s full face is quite visible. Of course it’s even more visible in the full-frame version. (Fussy Lang, or fussy somebody, seems to have aligned the face with the swoop of the ceiling.)

But the composition would look more awkward if chopped in the SuperScope 2.0:1 version. Here’s one framing, using the cropping points typical of other anamorphic shots in the European 35mm print.

In addition, since the crop slices more off the bottom region than the top, Walter’s body is also lost in the anamorphic version. But this is still probably the best compromise. Some frames in the 35mm S’Scope version favor the lower region of the original shot. But in this shot that option would be disastrous.

It’s hard to imagine that the director of the painstakingly composed Moonfleet (1955) would have wanted to saw Steven’s skull in half.

Mors ultima ratio

So Lang didn’t shoot the film expecting it to be SuperScoped. Nevertheless, things that escape directors’ intentions can have their own impact on viewers. In the codicil to the earlier blog entry, I wondered if French critics’ admiration for While the City Sleeps might have been based on their seeing wider prints than Americans did—in effect, gathering Lang into the cohort of skilled anamorphic filmmakers that included Ray, Preminger, Minnelli, et al. Samuel Bréan wrote to tell me that one critic, Jacques Lourcelles, raised this issue explicitly. Lourcelles writes:

For both this film and Lang’s next film, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, the format poses a thorny problem that can be resolved only by considering aesthetic matters. The film, not shot in CinemaScope, was exhibited in Superscope (a wide format used at RKO and created through laboratory processes), and then in a normal format. Which is better? In my opinion, the wider one. Only there, for instance, do the camera movements and the newspaper-office set have their true impact. Even if the Superscope version was “manufactured” in the lab, Lang knew that the film would be seen on the wide screen and his direction was conceived as a function of that. The same goes for Beyond a Reasonable Doubt; to cite just one instance, the first sequence showing the condemned man walking toward the electric chair is obviously conceived for the wider format.

This does lead to some intriguing speculation on how “misreadings” of films can have positive consequences. The French celebration of Lang’s 1950s films led American and British critics to reevaluate them.

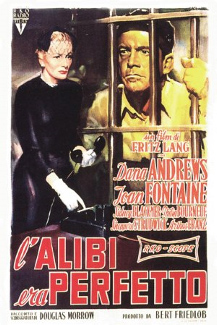

The case of Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is quite parallel to that of While the City Sleeps. Released in September 1956, it too was reviewed in Variety as a non-anamorphic picture. Its U. S. publicity makes no reference to a widescreen format. But its overseas posters claim that it is in “RKO-Scope.” Huh?

By the end of 1956, the Tushinskys had split from RKO and were selling SuperScope generally. So in November 1956 RKO simply announced that it had developed “a new widescreen, anamorphic process” that would carry a ratio of 2.0:1. Historians of widescreen have assumed that this is SuperScope by another name. The same publicity announced that soon all the studio’s films would be in RKO-Scope. But RKO ceased making movies on 1 January 1957. Universal took over distributing the remaining pictures.

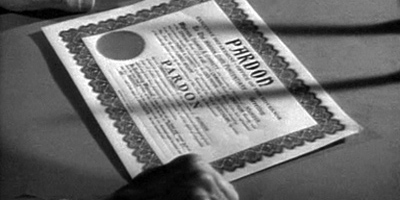

Again, on the basis of the posters and Lourcelles’ comments we can be confident that Beyond a Reasonable Doubt was shown in a 2.0:1 aspect ratio in some overseas markets. As airless a movie as Lang ever made, with disconcertingly generic sets and severe framings and camera movements, it engendered a fascination in French critics. The story itself is a model of Langian guilty conscience. A reporter looking for a new book to write agrees to a hoax that will attack capital punishment. He’ll plant clues indicating that he’s a murderer in order to prove that an innocent man can be convicted. Lang’s narration offers his customary feints and ellipses. Smooth hooks, verbal and visual, carry us across scenes. Casual details are dropped in, or a sudden cutaway appears, and we’re misled into thinking we’re ahead of the plot. We are in fact behind it. Crucial story information is skipped over, but we’re not aware of what has been deleted until much later. We should have noticed.

Appearing in the same year as Around the World in 80 Days, The King and I, Lust for Life, Giant, Anastasia, War and Peace, and other sweeping spectacles, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt was a bare-bones programmer. Lang’s last American film doesn’t waste its energy on the pictorial flourishes of budget-strapped directors like Siegel or Fuller. Other B-films could whip up visual flair with chiaroscuro, close-ups, and fast cutting, but Lang’s images seem disconcertingly banal; yet their simplicity gives them an odd purity. In an influential review, Jacques Rivette declared that Lang was, in effect, filming concepts.

I don’t find any shots in Beyond with a vertical bias comparable to the shot featuring Steven the butler in City. The 1.37 frame shots are very empty up top. So here’s an experiment in reconstructing an approximation of what Europeans saw.

Dux vitae ratio

As I suggested in the earlier blog, for decades Lang composed his frames carefully, balancing figures in dynamic patterns and sometimes putting important elements along the sides or in a corner. Here are some examples from one of his most beautiful films, The Ministry of Fear. He likes triangular compositions that tuck heads into corners, as well as camera angles that let foreground items anchor the faces and bodies.

When the frame is unbalanced, it’s for a reason, such as purse-rifling.

A director so committed (like Ozu) to putting heads high in the shot must have felt annoyed when he had to hang inexpressive space over his players, as in the shot at the very top of today’s entry. When he left headroom in earlier films, it served an exacting compositional purpose, as you see below. Those wedge-formations of tapers, backing up threatening cobras, look back to the decor of his German films.

I suspect that it pained him to accept the more open framing demanded by non-anamorphic ratios. In CinemaScope you could count, more or less, on the proportions of your image being respected. But shooting flat, could you really be sure what would stay in the shot? Projectionists could mask it to 1.66, 1.75, 1.85, and even wider. These ratios were so imprecise, and this is one precise director. Lang “shot to protect,” as they say, but he couldn’t protect what was already gone: his compact, quietly masterful compositions.

John Belton wrote to me to echo the idea that Lang would probably have realized that While the City Sleeps would be cropped to as much as 1.75.

Certainly every director after 1954 composed for wide screen projection. As for SuperScope, why didn’t they just project it flat with a 2:1 matte in the aperture? It certainly would have looked sharper. Maybe the answer lies in the relative abundance of CinemaScope installations overseas?

Good question for further research. Another interesting sidelight: Who was the SuperScope representative for Europe? For a time, apparently none other than Edgar G. Ulmer! Ulmer is identified as a SuperScope representative in “Tushinsky’s Teuton Deal,” Variety, 7 September 1956, p. 5. Michael Campi wrote to inform me that in Australia he too saw a 2.0:1 print of While the City Sleeps.

RKO’s announcement of RKO-Scope can be found in “And Now–RKO-Scope,” Variety, 30 November 1956, p. 1. More background on the winding down of the studio is provided in Richard B. Jewell and Vernon Harbin, The RKO Story (London: Octopus, 1982), pp. 242-245.

The Jacques Lourcelles comment appears in his Dictionnaire du cinéma vol. 3 (Paris: Laffont, 1992), p. 294. I’m grateful to Samuel Bréan for calling my attention to it. Rivette’s 1957 essay on Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, “The Hand,” is available in Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), pp. 140-144. It has been included in a site devoted to Jacques Rivette, Order of the Exile. (The hand Rivette refers to is that in the shot of the warrant above; had Rivette not seen the RKO-Scope print, he might have had to title the essay, “The Hands.”) The poster images for Beyond a Reasonable Doubt come from the ever-generous DVD Beaver, and its review of a Spanish disc.

The Ministry of Fear.