Legacies

Tuesday | September 4, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

By now James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma has had its critics’ screenings and sneak previews. It’s due to open this weekend. The reviews are already in, and they’re very admiring.

Back in June, I saw an early version as a guest of the filmmaker and I visited a mixing session, which I chronicled in another entry. I was reluctant to write about the film in the sort of detail I like, because I wasn’t seeing the absolutely final version and because it would involve giving away a lot of the plot.

I still won’t offer you an orthodox review of the film, which I look forward to seeing this weekend in its final theatrical form. Instead, I’ll use the film’s release as an occasion to reflect on Mangold’s work, on his approach to filmmaking, and on some general issues about contemporary Hollywood.

An intimidating legacy

It seems to me that one problem facing contemporary American filmmakers is their overwhelming awareness of the legacy of the classic studio era. They suffer from belatedness. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that this is a relatively recent development, and it offers an important clue to why today’s ambitious US cinema looks and sounds as it does.

In the classic years, there was asymmetrical information among film professionals. Filmmakers outside the US were very aware of Hollywood cinema because of the industry’s global reach. French and German filmmakers could easily watch what American cinema was up to. Soviet filmmakers studied Hollywood imports, as did Japanese directors and screenwriters. Ozu knew the work of Chaplin, Lubitsch, and Lloyd, and he greatly admired John Ford. But US filmmakers were largely ignorant of or indifferent to foreign cinemas. True, a handful of influential films like Variety (1925) and Potemkin (1925) made an impact on Hollywood, but with the coming of sound and World War II, Hollywood filmmakers were cut off from foreign influences almost completely. I doubt that Lubitsch or Ford ever heard of Ozu.

Moreover, US directors didn’t have access to their own tradition. Before television and video, it was very difficult to see old American films anywhere. A few revival houses might play older titles, but even the Museum of Modern Art didn’t afford aspiring film directors a chance to immerse themselves in the Hollywood tradition. Orson Welles was considered unusual when he prepared for Citizen Kane by studying Stagecoach. Did Ford or Curtiz or Minnelli even rewatch their own films?

With no broad or consistent access to their own film heritage, American directors from the 1920s to the 1960s relied on their ingrained craft habits. What they took from others was so thoroughly assimilated, so deep in their bones, that it posed no problems of rivalry or influence. The homage or pastiche was largely unknown. It took a rare director like Preston Sturges to pay somewhat caustic respects to Hollywood’s past by casting Harold Lloyd in Mad Wednesday (1947), which begins with a clip from The Freshman. (So Soderbergh’s use of Poor Cow in The Limey has at least one predecessor.)

Things changed for directors who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. Studios sold their back libraries to TV, and so from 1954 on, you could see classics in syndication and network broadcast. New Yorkers could steep themselves in classic films on WOR’s Million-Dollar Movie, which sometimes ran the same title five nights in a row. There were also campus film societies and in the major cities a few repertory cinemas. The Scorsese generation grew up feeding at this banquet table of classic cinema.

In the following years, cable television, videocassettes, and eventually DVDs made even more of the American cinema’s heritage easily available. We take it for granted that we can sit down and gorge ourselves on Astaire-Rogers musicals or B-horror movies whenever we want. Granted, significant areas of film history are still terra incognita, and silent cinema, documentary, and the avant-garde are poorly served on home video. Nonetheless, we can explore Hollywood’s genres, styles, periods, and filmmakers’ work more thoroughly than ever before. Since the 1970s, the young American filmmaker faces a new sort of challenge: Now fully aware of a great tradition, how can one keep from being awed and paralyzed by it? How can a filmmaker do something original?

I don’t suggest that filmmakers have decided their course with cold calculation. More likely, their temperaments and circumstances will spontaneously push them in several different directions. Some directors, notably Peckinpah and Altman, tried to criticize the Hollywood tradition. Most tried simply to sustain it, playing by the rules but updating the look and feel to contemporary tastes. This is what we find in today’s romantic comedy, teenage comedy, horror film, action picture, and other programmers.

More ambitious filmmakers have tried to extend and deepen the tradition. The chief example I offer in The Way is Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire, but this strategy also informs The Godfather, American Graffiti, Jaws, and many other movies we value. I also think that new story formats like network narratives and richly-realized story worlds have become creative extensions of the possibilities latent in classical filmmaking.

James Mangold’s career, from Heavy onward, follows this option, though with little fanfare. He avoids knowingness. He doesn’t fill his movies with in-jokes, citations, or homages. Instead, he shows the continuity between one vein of classical cinema and one strength of indie film by concentrating on character development and nuances of performance. In an industry that demands one-liners and catch-phrases sprinkled through a script, Mangold offers the mature appeal of writing grounded in psychological revelation. In a cinema that valorizes the one-sheet and special effects and directorial flourishes, he begins by collaborating with his actors. He is, we might say, following in the steps of Elia Kazan and George Cukor.

Sandy

By his own account, Mangold awakened to these strengths during his formative years at Cal Arts, where he studied with Alexander Mackendrick. Mackendrick directed some of the best British films of the 1940s and 1950s, but today he is best known for Sweet Smell of Success.

Seeing it again, I was struck by the ways that it looks toward today’s independent cinema. It offers a stinging portrait of what we’d now call infotainment, showing how a venal publicist curries favor with a monstrously powerful gossip columnist. It’s not hard to recognize a Broadway version of our own mediascape, in which Larry King, Oprah, and tmz.com anoint celebrities and publicists besiege them for airtime. While at times the dialogue gets a little didactic (Clifford Odets did the screenplay), the plotting is superb. Across a night, a day, and another night, intricate schemes of humiliation and aggression play out in machine-gun talk and dizzying mind games. It’s like a Ben Jonson play updated to Times Square, where greed and malice have swollen to grandiose proportions, and shysters run their spite and bravado on sheer cutthroat adrenalin.

Sweet Smell was shot in Manhattan, and James Wong Howe innovated with his voluptuous location cinematography. “I love this dirty city,” one character says, and Wong Howe makes us love it too, especially at night.

Today major stars use indie projects to break with their official personas, and the same thing happens in Mackendrick’s film. Burt Lancaster, who had played flawed but honorable heroes, portrayed the columnist J. J. Hunsecker with savage relish. “My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in thirty years,” he remarks. Tony Curtis, who would go on to become a fine light comedian, plays Sidney Falco as a baby-faced predator, what Hunsecker calls “a cookie full of arsenic.” Falco is sunk in petty corruption, ready to trade his girlfriend’s sexual favors for a notice in a hack’s column. Hunsecker and Falco, host and parasite, dominator and instrument, are inherently at odds, then in a breathtaking scene they double-team to break the will of a decent young couple. There are no heroes. Nor, as Mangold points out in his Afterword to the published screenplay, do we find any of that “redemption” that today’s producers demand in order to brighten a bleak story line.

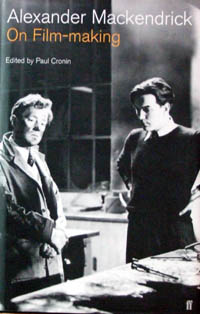

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mangold became a willing apprentice to Mackendrick. “He taught me more craft than I could articulate, but beyond that, he showed me how hard one had to work to make even a decent film.” (1) Mangold’s afterword to the Sweet Smell screenplay offers a precise dissection of the first twenty minutes. He shows how the script and Mackendrick’s direction prepare us for Hunsecker’s entrance with the utmost economy. Mangold traces out how five of Mackendrick’s dramaturgical rules, such as “A character who is intelligent and dramatically interesting THINKS AHEAD,” are obeyed in the film’s first few minutes. The result is a taut character-driven drama, operating securely within Hollywood construction while opening up a sewer in a very un-Hollywood way. Surely Sandy Mackendrick’s boldness helped Mangold find his own way among the choices available to his generation.

Movies for grownups

Mangold has often mentioned his love for classic Westerns; on the DVD commentary for Cop Land he admits that he wanted it to blend the western with the modern crime film. But why Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma?

The Searchers, Rio Bravo, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance were objects of veneration for directors of the Bogdanovich/ Scorsese/ Walter Hill generation, while Yuma seemed to be a more run-of-the-mill programmer. To American critics in the grips of the auteur theory, Delmer Daves sat low in the canon, and Glenn Ford and Van Heflin offered little of the star wattage yielded by John Wayne, James Stewart, and Dean Martin. In retrospect, though, I think that you can see what led Mangold to admire the movie.

For one thing, it’s a close-quarters personal drama. It doesn’t try for the mythic resonance of Shane or The Searchers or Liberty Valance, and it doesn’t relax into male camaraderie as Rio Bravo does. The early Yuma simply pits two sharply different men against one another. Ben Wade is a robber and killer who is so self-assured that he can afford to be courteous and gentle on nearly every occasion. Dan Evans is a farmer so beaten down by bad weather, bad luck, and loss of faith in himself that he takes the job of escorting the killer to the train depot.

That dark glower that made Glenn Ford perfect for Gilda and The Big Heat slips easily into the soft-spoken arrogance of Wade. His self-assurance makes it easy for him to play on all of Evans’ doubts and anxieties. In counterpoint, Van Heflin gives us a man wracked by inadequacy and desperation; his flashes of aggression only betray his fears. In the end, his courage is born not of self-confidence but of sheer doggedness and a dose of aggrieved envy. He has taken a job, he needs the money to provide for his family, and, at bottom, it’s not right that a man like Wade should flourish while Evans and his kind scrape by. As in Sweet Smell of Success, the drama is chiefly psychological rather than physical, and the protagonist is far from perfect.

Daves shows the struggle without cinematic flourishes, in staging and shooting as terse as the prose in Elmore Leonard’s original story. Deep-focus images and dynamic compositions maintain psychological pressure, and as ever in Hollywood films, undercurrents are traced in postures and looks, as when Wade in effect takes over Evans’ role as father at the dinner table.

One more factor, a more subliminal one, may have attracted Mangold to Daves’ western. 3:10 to Yuma was released in 1957, about two months after Sweet Smell of Success. Both belong to a broader trend toward self-consciously mature drama in American movies. Faced with dwindling audiences, more filmmakers were taking chances, embracing independent and/or East Coast production, and offering an alternative to teenpix and all-family fare. 1957 is the year of Bachelor Party, Twelve Angry Men, Edge of the City, A Face in the Crowd, The Garment Jungle, A Hatful of Rain, The Joker Is Wild, Mister Cory (also with Tony Curtis), No Down Payment, Pal Joey, Paths of Glory, Peyton Place, Run of the Arrow, The Strange One, The Tarnished Angels, The Three Faces of Eve, Twelve Angry Men, and The Wayward Bus. These films and others featured loose women, heroes who are heels, and “adult themes” like racial prejudice, rape, drug addiction, prostitution, militarism, political corruption, suburban anomie, and media hucksterism. (Who says the 1950s were an era of cozy Republican values and Leave It to Beaver morality?) Today many of these films look strained and overbearing, but they created a climate that could accept the doggedly unheroic Evans and the proudly antiheroic Sidney Falco.

3:10 x 2

Mangold’s remake is a re-imagining of Daves’ film, more raw and unsparing. Both films give us the journey to town and a period of waiting in a hotel room. In the original, Daves treats the sequences in the hotel room as a chamber play. Each of Wade’s feints and thrusts gets a rise out of Evans until they’re finally forced onto the street to meet Wade’s gang and the train. Mangold has instead expanded the journey to the railway station, fleshing out the characters (especially Wade’s psychotic sidekick) and introducing new ones. This leaves less space for the hotel room scenes, which are I think the heart of Daves’ film.

At the level of imagery, the new version is firmly contemporary. The west is granitic; men are grizzled and weatherbeaten. When Wade and Evans get into the hotel room, Daves’ low-angle deep-focus compositions are replaced by the sort of brief singles that are common today. As in all Mangold’s work, minute shifts in eye behavior deepen the implications of the dialogue.

Similarly, the cutting, the speediest of any Mangold film, is in tune with contemporary pacing. At an average of 3 seconds per shot, it moves at twice the tempo of Daves’ original. Mangold has been reluctant to define himself by a self-conscious pictorial style. “I think writer-directors have less of a need sometimes to put a kind of obvious visual signature over and over again on their movies . . . . I don’t need to go through this kind of conscious effort to become the director who only uses 500mm lenses.” (2)

Mangold puts his trust in well-carpentered drama and nuanced performances. Daves begins his Yuma with Wade’s holdup of a stage, linking his movie to hallowed Western conventions, but Mangold anchors his drama in the family. His film begins and ends with Evans’ son Bill, who’s first shown reading a dime novel. We soon see his father, already tense and hollowed-out. At the end Mangold gives us a resolution that is more plausible than that of Leonard’s original or Daves’ version. What the new version loses by letting Evans’ wife Alice drop out of the plot it gains by shifting the dramatic weight to Bill in the final moments. The conclusion is drastically altered from the original, and it shocked me. But given Mangold’s admiration for the shadowlands of Sweet Smell, it makes sense.

In an interview Mangold remarks that Mackendrick distrusted film school because it stressed camera technique and didn’t prepare directors to work with actors. “It’s a giant distraction in film schools that in a way, by avoiding the world of the actor, young filmmakers are avoiding the most central relationship of their lives in the workplace.” (3) As we’d expect from Mangold’s other films, the central performances teem with details. Bale cuts up Crowe’s beefsteak, and Crowe gestures delicately with his manacles when he softly demands that the fat be trimmed. Bale’s gaunt, limping Evans, a Civil War casualty, becomes an almost spectral presence; his burning glances reveal a man oddly propelled into bravery by his failures. Crowe’s Ben Wade, for all his intelligence and jauntiness, is oddly unnerved by this farmer’s haunted demeanor. Actors and students of performance will be kept busy for years studying the two films and the way they illustrate different conceptions of the characters and the changes within mainstream cinema.

Sometimes I think that Hollywood’s motto is Tell simple stories with complex emotions. The classic studio tradition found elemental situations and used film technique and great performers to make sure that the plot was always clear. Yet this simplicity harbored a turbulent mixture of contrasting feelings, different registers and resonances, motifs invested with associations, sudden shifts between sentiment and humor. In his commitment to vivid storytelling and psychological nuances, Mangold has found a vigorous way to keep this tradition alive. Sandy would have been proud.

(1) James Mangold, “Afterword,” Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman, Sweet Smell of Success (London: Faber, 1998), 165.

(2) Quoted in Stephan Littger, The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century (New York: Continuum, 2006), 317.

(3) Quoted in Littger, 313.

PS 9 Sept: Susan King’s article in the Los Angeles Times explains that Mangold first got acquainted with Daves’ film in Mackendrick’s class. “We would break down the dramatic structure of the film. This one really got under my skin, partly because it always really moved me. It also felt original in scope in that it was very claustrophobic and character-based.” King’s article gives valuable background on the difficulties of getting the film produced.