Bwana Beowulf

Friday | December 7, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

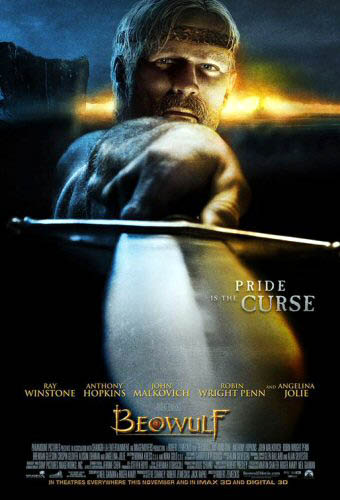

KT: I do not understand Beowulf. I don’t understand why the director who made one of the great modern Hollywood films, Back to the Future, and several very good ones, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and Cast Away, now has this fixation with creating nearly photo-realistic 3D digital images.

DB: I think that on the whole Zemeckis’ films have become weaker since Bob Gale stopped working with him. I like the sentiment of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and the crass misanthropy of Used Cars, and I think the Back to the Future trilogy mixes both in clever ways. But now almost every Zemeckis film seems to be less about telling a story than solving a technical problem. How to best merge cartoons and humans (Roger Rabbit)? How to push the edge of spfx (Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact)? How to make half a movie showing only one character (Cast Away)? There’s a stunting aspect to this line of work, though I grant that it can lead to technical breakthroughs, as in Gump.

KT: I also don’t understand why most of the supposedly state-of-the-art effects technology looks distinctly cruder than the CGI in The Lord of the Rings, the first part of which came out six years ago. I don’t understand why studios that are trying to push 3D to a broad audience make a film with silly action aimed at teenage boys. That’s an OK strategy when you’ve got a $30 million horror film, but a budget of $150 million demands a lot broader appeal.

DB: And the evidence so far indicates Beowulf doesn’t have that appeal. The obvious comparison is 300, from earlier this year. According to Box Office Mojo it cost about $65 million to make, but it reaped $70 million domestically in its first weekend and wound up with $450 million theatrically worldwide. Beowulf grossed $27.5 million in its first US weekend and currently sits at about $146 million worldwide. I’d think that this has to be a disappointment. Recall too that the Imax screenings have higher ticket prices, so there are fewer eyeballs taking in Angelina Jolie’s pumps, braid, and upper respiratory area.

In addition, sources suggest that a 3-D version of Beowulf will not be available on DVD, so the sell-through takings—the real source of studio profit—may be significantly smaller than average.

KT: It seems to me that the people who are pushing 3-D so hard and hoping for it to become standard in filmmaking are forcing it on the public too soon. It’s still fiendishly difficult and expensive to shoot live action material in digital 3-D, so most projects are animated. One approach, taken in Beowulf, is to motion-capture real people and animate the characters to make them appear as much like the real people as possible. The problem is that they still have a weird look about them, like moving dolls. People have complained about the dead-eyed gaze of the characters in The Polar Express, and though there’s apparently been an improvement between the two films, the eyes don’t always look as though they’re focusing on anything. It can be done, though; the extended-edition Lord of the Rings DVD supplements about Gollum show how much effort went into making his eyes have a realistic sheen and flicker.

I was also struck by how clunky some of the animation looked. Beowulf is supposedly state of the art, and it certainly had the budget of a major CGI film. Yet some of the rendering and motion-capture was distractingly crude. I noticed that particularly on the horses. Their coats looked pre-Monsters, Inc., and their movements at times reminded me of kids rocking plastic toys back and forth. I suspect this effect had something to do with a lack of believable musculature. If you look at the way the cave troll was done in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (again, demonstrated in the DVD supplements), there was a specific program to simulate the way muscles move on skeletons, even the skeletons of imaginary creatures. Now, six years later, we see these things that look like hobby-horses—and that all run alike.

The backgrounds were often strange as well, simple and flat-looking, like painted backdrops. There were some exceptions, with the seascapes and rocky crags pretty realistically done. But just plain hillsides and groups of tents and so on looked almost sketchy in comparison with the moving figures, and I noticed that at times some fog would be put in, presumably to cover that problem up. There certainly was some very good animation as well, most notably the dragon, but there was no consistency of visual style.

DB: I’d go farther and say that 3-D hasn’t improved significantly since the 1950s. It ought to work: just replicate the eyes’ binocular disparity by setting two cameras at the proper interval or, now, by manipulating perspective with software. Yet in films 3-D has always looked weirdly wrong. It creates a cardboardy effect, capturing surfaces but not volumes. Real objects in depth have bulk, but in these movies, objects are just thin planes, slices of space set at different distances from us. If our ancestors had seen the world the way it looks in these movies, they probably wouldn’t have left many descendants.

It would take a perceptual psychologist to explain why 3-D looks fake. Whatever the cause, I’d speculate that good old 2-D cinema is better at suggesting volumes exactly because the cues to depth are less specific and so we can fill in the somewhat ambiguous array.

By the way, in watching a 3-D movie I seem to go through stages. First, there’s some adjustment to this very weird stimulus: I can’t easily focus on the whole image and movement seems excessively fuzzy. Then adaptation settles in and I can see the 2 ¼-D image pretty well. But adaptation carries me further and by the end of the movie I seem to see the image as less dimensional and more simply 2-D; the effects aren’t as striking. But maybe this is just me.

Back to the Future, or at least 1954

DB: I’d like to think about it from a historical perspective for a while. The industry seems to be repeating a cycle of efforts that took place in 1952-1954. The American box office plunged after 1947 as people strayed to other entertainments, including TV, and so the industry tried to woo them back with some new technology. Today, as viewers migrate to videogames, the Internet, and movies on portable devices, how can theatres woo their customers? Answer: Offer spectacle they can’t get at home.

Beowulf brings together at least three factors that eerily remind me of the early 1950s.

(1) Obviously, 3-D. The first successful 3-D feature era was Bwana Devil, released in November of 1952. It was an uninspired B movie, but it launched the brief 3-D craze. Columbia, Warners, and other studios made major pictures in the format, most notably House of Wax (1953). But costs of shooting and screening 3-D were high, with many technical glitches, and apart from novelty value, the process didn’t guarantee a big audience. The fad ended in spring of 1954, when all studios stopped making films in the format.

The process has been sporadically revived, notably in the 1980s (Comin’ at Ya, Jaws 3-D) and once more it fizzled. So, ignoring the lessons of history and chanting the mantra that Digital Changes Everything, we try it again.

(2) Big, big screens. In September of 1952, Cinerama burst on the scene with its huge tripartite screen and multitrack sound. It attracted plenty of viewers, but it could be used only in purpose-built venues. Like 3-D, its technology could never replace ordinary 35mm as the industry standard. The contemporary parallel is Imax, which though very impressive will not replace orthodox multiplex screens—too expensive to install and maintain, pricy tickets. Like 3-D, it’s a novelty. (1)

(3) The sword-and-sandal costume epic. It’s a long-running genre, but it got significantly revived in the late 1940s. It was a logical input for the new technologies of widescreen—not Cinerama but more practical offshoots that gained more general usage.

From the standard-format Samson and Delilah (1949), David and Bathsheba (1951), and Quo Vadis (1951) it was a short step to The Robe (1953) and The Egyptian (1954) in CinemaScope, The Ten Commandments (1956) in VistaVision, The Vikings (1958) in Technirama, Hercules (1959) in Dyaliscope, Solomon and Sheba (1959) and Spartacus (1960) in Super Technirama 70, and Ben-Hur (1959) in anamorphic 70mm Panavision. It is, incidentally, a pretty dire genre; the peplum might be the only genre that has given us no great films since Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916).

In parallel fashion, the revival of the beefcake warrior film with Gladiator (2000) coincided with innovations in CGI and thus furnished new forms of spectacle for Troy (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and 300 (2007). This trend paved the way for Beowulf. When screens get bigger, Hollywood hankers for crowds, oiled biceps, big swords, and nubile ladies in filmy clothes. Not to mention soundtracks with pounding drums, wailing sopranos, and choirs chanting dead or made-up languages. And the conviction that Greeks, Romans, and those other ancient folks spoke with British accents. The innovation of Beowulf is to turn a Nordic hero into a Cockney pub brawler.

In other words, it’s 1954 again. So if we ask, Will it all last? I’m inclined to answer, Did 1954?

KT: Yes, the studios see the new technology as one more way to lure people away from their computers and game consoles and into the theaters. Maybe that will work to some extent. There’s no doubt that a lot of the people who have seen Beowulf have praised it as a fun experience and as having effectively immersive 3-D effects. I’m surprised at how many positive comments there are on Rotten Tomatoes, where the average score from both amateur and professional reviewers is 6.5 out of 10. That’s not exactly dazzling, but it’s a lot higher than I would give it.

Even so, the film hasn’t lured all that many people away from their other activities. You’ve mentioned that Beowulf hasn’t done all that well at the box-office. It did much better in theaters that showed it in 3-D. If it hadn’t been for the 3-D gimmickry, it would probably have been dead in the water from the start. And if 3-D effects remain on the level of gimmickry, they will soon wear out their welcome. Presumably the people who have been going to Beowulf are to a considerable extent those who are already interested in 3-D, and I can’t believe there are huge numbers of people really passionate about the idea of someday being able to watch lots of films in 3-D. If more films like Beowulf come out—ludicrous, bombastic action with distracting animation problems—they’re not likely to make the prospect any more attractive.

Eventually somebody—James Cameron or Peter Jackson, perhaps—will make the first great 3D film, and then maybe the passion will spread.

3-D in 2-D

DB: I’m doubtful that there will ever be a great 3-D film, and especially from those directors. But one last historical note.

I think that ordinary mainstream cinema has been setting us up for the flashiest 3-D flourishes for some time. One of the goals of the Speilberg-Lucas spearhead was to amp up physical action, to make it more kinetic, and this often showed up as in-your-face depth. Spielberg used a lot of deep-focus effects to create a punchy, almost comic-book look, and who can forget the opening shot of Star Wars, with that spacecraft arousing gasps by simply going on into depth forever? Seeing the movie in 70mm on release, I was struck by how the last sequence of Luke’s attack mission was maniacally concerned with driving our eye along the fast track of central perspective. Did it foreshadow the tunnel vision of videogame action?

In any case, I think that aggressive thrusting in and out of the frame was integral to the style of the new blockbuster. Since then, our eyes have been assaulted by plenty of would-be 3-D effects in 2-D. In Rennie Harlan’s Driven (2001), the crashing race cars spray us with fragments.

Jackson is definitely in the Spielberg line, favoring steep depth and big foreground elements. In King Kong, the primeval creatures lunge out at us, heave violently across the frame, and fling their victims into our laps.

Such shock-and-awe shots recall American comic-book graphics. These affinities are at the center of 300, as we’d expect. For example, a cracking whip curls out at us in slow motion, like a two-panel series.

Beowulf draws on this thrusting imagery, but inevitably it doesn’t seem fresh because so many 2-D films have already used it. Maybe the most original device is having the camera pull swiftly back and back and back, letting new layers of foreground pop in and shrink away. This is viscerally arousing in 3-D, but aren’t there precedents for it—in the Rings, in animated films, or some such?

Zemeckis tries to transpose into 3-D the style of what I’ve called, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity. This style favors rapid cutting, many close views, extreme lens lengths, and lots of camera movement. I found Zemeckis’ restless camerawork even more distracting than in 2-D. So I’m wondering if current stylistic conventions can simply be transposed to 3-D, or do directors have to be more imaginative and make fresher choices?

KT: That pull-back effect may be viscerally arousing, but in Beowulf it was usually pretty gratuitous and, for me at least, it called attention to itself in a way that was often risible. I don’t think there’s anything in Rings as crude as the shots in Beowulf that you’re talking about. In the opening scene of the latter, in the mead-hall, the camera zips into the upper part of the room, with rafters, chains, torches, and even rats whizzing in from the sides of the frame. None of that contributes to the narrative.

The flashiest backward camera movement, or simulated camera movement, I can think of in Rings is the one in the Two Towers scene where Saruman exhorts his army of ten thousand Uruk-hai to battle. The final shot is a rapid track backward through the ranks of soldiers holding flag poles. The point is to stress the enormous numbers of soldiers. There’s no gratuitous thrusting-in of set elements from the sides, just the cumulative effect of so many similar figures. The simulated camera also at one point “bumps” one of the flagpoles, causing it to wobble, but I take it that that’s an attempt to add a certain odd realism to the “camera” movement, not a knowing nudge to the audience. In Rings, the virtual camera usually follows action rather than moving independently through space. It tends to go forward or obliquely rather than backward.

As to transferring classical Hollywood style to 3-D or finding a whole new set of conventions to fit 3-D, Beowulf offers an object lesson. It uses a combination of the two. At times we have conventional conversations using shot/reverse shot, and at other times we have the swoopy-glidey style you described, with the camera zipping around the space and trying to see it from every angle within a few seconds.

The odd thing is, neither one works. The very close shot/reverse shot views of the digital characters make them look unnatural and emphasizes the not infrequent failure of their eyes to connect with each other. The swoop-glidey camera movements are silly and don’t stick to the narrative.

I’m not optimistic enough to think that directors can come up with a whole set of “fresher stylistic choices” to make 3-D work. Maybe Sergei Eisenstein, with his meticulous attention to every aspect of such topics, could have thought the issue through, but his solution would probably not be viable for the Hollywood studios. My own thought is that directors working in 3-D should probably stick to classical Hollywood style and avoid flashy stylistic effects. So far, the more blatantly 3-D something looks on the screen, the less it makes 3-D seem like something we want to watch on a regular basis. Think of the best films of this year: Zodiac, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Ratatouille, Across the Universe, and so on. Would any of them be better in 3-D? Probably not.

Plus, I don’t like watching movies through something. Movies should just be the screen and you. The 3-D glasses are definitely better now than in the earliest days of the cardboard, red/green versions. Still, the Imax glasses we used in watching Beowulf were heavy enough to leave a groove on my nose. Make the mistake of touching the lenses, and you’ve got a blur on one half of your vision of the film. In short, I think that 3-D still has to prove itself, and Beowulf didn’t add any evidence.

(1) PS 9 December: DB: I originally added in regard to Imax: “It’s actually waning in popularity, except in newly emerging markets like China.” This disparaging comment was misleading. Yesterday I learned from Screen International that Imax recently signed a deal with AMC to install 100 systems in 33 US cities. Oops! Today Paul Alvarado Dykstra of Austin’s Villa Muse Studios kindly wrote to point out the Hollywood Reporter‘s coverage, which gives background on the costs of installing and maintaining an Imax facility.

I was, obscurely, thinking of the traditional Imax programming of travelogues and documentaries. I failed to register that these have been largely displaced by screenings of blockbuster features, catching fire in 2003 with The Matrix Reloaded and proving successful with The Polar Express and other titles. Imax is now largely an alternative venue for megapictures, and its seesawing financial performance may have been steadied by moving into the features market.

PS 26 December: Travel has delayed our timely linking, but we couldn’t neglect Mike Barrier’s in-depth critique of Beowulf here.

PPS 5 January 2008: Harvey Deneroff has a comprehensive and judicious discussion of the 3D situation here.