Our voyage to Italy

Wednesday | December 19, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

“You’d better get going on a blog entry.”

“Aw, you write it.”

“No, you do it.”

“No, you do it.”

“Okay, let’s both do it.”

KT:

In keeping with our attempts to bring you information on cinema and the arts from around the world, we offer this entry from Naples, Italy. Our old friend Vito Zaggario invited us to present papers at a conference in Rome, “Una narrazione esplosa?” December 17 and 18.

We decided to take advantage of the opportunity to go early and visit Pompeii and Herculaneum, two of the spots on our must-see list. We based ourselves in Naples because the sites are a short train ride away.

How could we go to Naples and not think of cinema? An early great Neopolitan movie is Assunta Spina (1915), starring one of the foremost Italian divas of the era, Francesca Bertini. Naturally, though, the first one that came to mind was Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (1954). Some of the places that Catherine (Ingrid Bergman) and Alexander (George Sanders) visit in the film still exist, so we went looking for them. Fortunately, we had no quarrels or plans for divorce, but we didn’t encounter any miracles during a street procession either. About all we saw on the sidewalks were piles of trash, a recurrent problem because of strikes and the camorra’s role in the waste-removal business.

The restaurant Bersagliera, where Catherine watches Alexander flirt with another woman, is still there, a Naples landmark. It’s been somewhat redesigned, but is still very recognizable. In one corner a display of photos of luminaries who have dined at the Bersagliera includes snaps of Claudia Cardinale, Monica Vitti, and the wonderful local comedian Totò (below). Of course there’s also a signed two-shot of Ingrid and Roberto.

The seafood pasta, veal, and pepper steak were delicious, and not horribly expensive, even with the American dollar so low against the Euro.

Reminders of current cinema were evident in two billboards across from our hotel. As you know, American movie stars who would not compromise their dignity by appearing in ads in the U.S. routinely endorse products in other countries. Here a smiling Nicholas Cage publicizes a Mont Blanc watch.

Right next to him was a billboard touting a new Italian comedy, Natale in crociera (“Christmas on a Cruise”). As I mentioned in an earlier entry, there are popular comedies made in a lot of foreign markets that we never hear of in the U.S. This is one of them. It’s the sixth in the popular Natale series, which, as the name suggests, are released in the Christmas season. Its director, Neri Parenti, also directed the ten Fantozzi comedies. Who says only Hollywood makes sequels and series?

We didn’t try to go to any movies while we were there. For one thing, we were busy in the evenings reading up on Pompeii and Herculaneum. For another, virtually all films shown in Italy are dubbed, and we don’t speak Italian.

Many of the artifacts found in the two ancient cities are on display in Naples’ National Museum of Archaeology. We decided to devote our first day to a visit there, hoping that seeing the decoration and artifacts found at the sites would give us a better sense of what the cities would have been like before 79 A.D., when a huge eruption of Vesuvius buried and preserved them.

Some more or less non-moving pictures

DB:

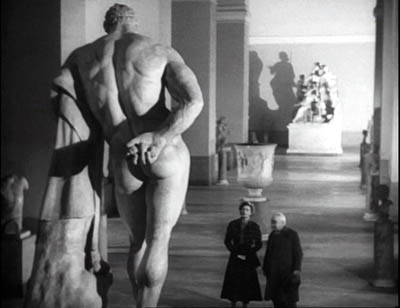

Not all the objects in the museum came from Pompeii and Herculaneum. I was especially eager to check on the statue of Hercules in the Farnese Collection. It appears in one of the finest scenes in Voyage to Italy, and though I couldn’t get Rossellini’s high angle, evidently made with a crane, it was possible to approximate his shot.

The collections at the two museums we visited, the archeological museum and the Capodimonte Museum, were spectacular and induced me, as museum trips do, to think about images, both still and moving. (Here and here are previous musings on the subject.)

Since I’m planning a book touching on relations between cinema and the pictorial arts, these come under the heading of Research as well as that of Fun. I got several ideas, but I’ll mention just two images that grabbed me.

While devoted mostly to ancient art, the Archaeological Museum was holding an exhibition of more recent painting and sculpture that dealt with classic themes, Pompeii among others. There were several quite interesting nineteenth-century narrative paintings there, but I saw nothing bolder in its compositional design than this 1896 piece by Giulio Bargolini on the Pygmalion story.

I like the way Galatea comes to life in the upper left cranny of the frame, while Pygmalion, recoiling from what he has created, is daringly off-center. His staggering is emphasized by all the space behind him that he can fall into.

Still, the National Museum’s showpieces are from antiquity, and one of its masterpieces is the Pompeii floor mosaic showing Alexander’s victory over Darius. Made around 200 BC, it’s presumed to be a copy of a Greek painting.

I’ve been keen to see it since first encountering it in E. H. Gombrich’s magisterial Art and Illusion, a book that decisively shaped my thinking about film. Gombrich discusses the image as an example of the Greek discovery of the “eyewitness” principle, the strategy of representing a scene as it might look to an observer.

It certainly does that. Scanning the mosaic, I was reminded of the almost snapshot quality of its rendition of the battle. The left half is mostly gone, with the profile of Alexander the most intact bit. The right half, showing Darius’ forces at once resisting and fleeing, is a dazzling image.

The thrusting spears and Darius’ outflung hand create a vivid thrust to the center, but the wheeling horses and plunging chariots counter this as they retreat to the right. There’s a remarkable amount of foreshortening, as with the horse’s rump in the center. We find shading and wrinkles on sleeves, and even Darius’ knuckles seem white with fear. I had never realized the amount of detail that could be captured in the mosaic medium.

The thrusting spears and Darius’ outflung hand create a vivid thrust to the center, but the wheeling horses and plunging chariots counter this as they retreat to the right. There’s a remarkable amount of foreshortening, as with the horse’s rump in the center. We find shading and wrinkles on sleeves, and even Darius’ knuckles seem white with fear. I had never realized the amount of detail that could be captured in the mosaic medium.

Critics have long noted the small vivid touches, such as the shocked expression on Darius’ face, the grim charioteer beside him, and the fallen soldier who glimpses his own doleful face reflected in a shield.

What struck me just as much as the freeze-frame action was the ways that the figures get tangled up. Later academic paintings of battles, of which the Capodimonte museum seems to have thousands, tend to separate out each important face and figure, with empty air framing them. Not this mosaic, which in certain parts creates a sense of frenzied panic by piling up gestures and body parts.

Clearly the artist knew how to pull a figure out of the melée. Darius is starkly isolated, by virtue of his height in the format and the empty space surrounding him. But behind and beneath him and his whip-cracking charioteer, his forces are in tumult. To look at just one bit: Here the snapshot quality is evident—the whip curls in mid-air—but in the lower right there’s also a collage of hands, heads, and single eyes of men and horses, cued by simple overlap.

The sheer pressure of the confusion, the tension between retreating and standing fast, is rendered by these tightly stacked planes, crisscrossed by the diagonals of spears and the charioteer’s arm. I can imagine Eisenstein calling this an early case of montage, the colliding stimuli that create a synthetic, expressive image.

Sights and sites

KT:

Pompeii did not disappoint. December in Italy can be cold and rainy, but we were lucky and had sunny cool weather for our visit. Going during the off-season is definitely a good idea.

We were alone in some parts of the site, including the beautifully preserved amphitheater. It took us about six hours to walk from one end of the excavated portion to the other, though one could easily spend two days going slowly and savoring the bits of wall paintings and mosaics that have not been taken away to the museum, as well as the marble-tiled counters in the many bars and cafes, the steep, curving bleachers in the small and large theaters, and the many faint graffiti written by the ancient citizens. Almost everywhere one goes, the vast, looming presence of Vesuvius dominates the view.

The next day it turned much colder and very windy, though still sunny. The fact that the excavated portion of Herculaneum is in a vast pit helped protect us from the wind. Vesuvius’ mud and ashes buried the city 65 feet under current ground level. Again we encountered only a few other tourists as we strolled up and down the sidewalks of the town, looking into the houses, the taverns, and the temples. Again much of the wall decoration had been removed, but there were enough tile floors, mosaics, painted panels, and furniture to give a better sense of what the place must have looked like.

More on the Rome part of the trip later.