Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun

Friday | December 8, 2006 open printable version

open printable version

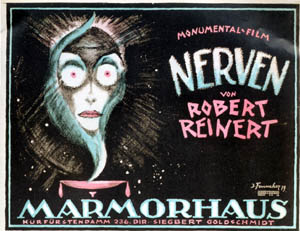

1. “It hypnotizes the viewer,” writes Paul van Yperen of the Nerven poster he printed in the new issue of the Dutch journal Skrien. Paul sent it to me because I wrote about Robert Reinert’s film in my forthcoming collection of essays, Poetics of Cinema. Nerven is a disorienting, highly experimental work. Released in 1919, before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (early 1920), it might have become a prototype of German Expressionist cinema if it had been widely seen and preserved by archives. Nerven, along with Reinert’s other major film Opium (1919) would make a wonderful twofer on a DVD release.

2. We’ve set up an archival supplement to our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction elsewhere on this site. It includes analyses that appeared in earlier editions but were cut for reasons of space or film availability.

The pieces discuss Stagecoach, Hannah and Her Sisters, Desperately Seeking Susan, Day of Wrath, Last Year at Marienbad, Innocence Unprotected, Disney’s Clock Cleaners, Tout va bien, High School, and Hitchcock’s first Man Who Knew Too Much. DVD has made nearly all of these films easily accessible, so we hope reviving the essays will be of use to students and free-ranging viewers.

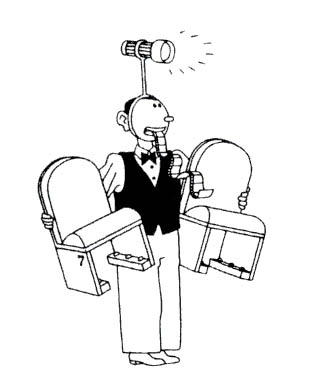

3. Check out the nifty interview with Joost Swarte in the new issue of The Comics Journal. Excerpts are here.

Swarte is the greatest heir to the Belgian-Dutch “clear-line” style, and his witty cartoons have become worldwide classics. Kristin and I have been collecting Swarte books and posters since the 1980s, although as his projects have expanded to building design his output of images has waned (except for the occasional item for The New Yorker).

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

He was very much influenced by cinematographic laws. Where do you place your camera? Is the hero always coming from the left? What’s the relation between foreground and background? All sorts of terms that he used come from cinema.

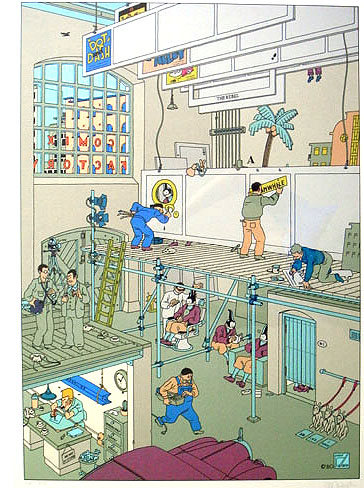

Swarte too has an affinity for film. One of his best pictures, Comic Factory, treats cartooning as if it were moviemaking. Our cartoonist labors in lower left, the girder of a deadline hanging above him, while a producer (with cigar) seems to be telling the photographer how to shoot the panels. Jopo de Pojo gets spruced up for his close-up while his doubles (or clones) lounge around. Set designers and scene painters labor over the panels.

Swarte’s teeming street scenes, usually including dog turds, are filled with glimpsed gags in the manner of Tati. Not surprising, then, that under the skilful questioning of David Peniston, he confesses his admiration for Play Time. New collections of Swarte’s comics are apparently forthcoming, in several languages, in 2007. By the way, the same issue of the Journal has a nice appreciation of Cliff Sterrett, another comics genius, creator of the amiable, lovely, and quite nuts Polly and Her Pals. Click here for a nice blow-up sample.

4. Speaking of cinema in still images: One of Eisenstein’s favorite pastimes was to find anticipations of film in earlier media. He loved the fact that Myron’s discus thrower was portrayed in an impossible position, with the limbs indicating different phases of the action.

This and similar items were inspirations for the plate-smashing scene in Potemkin.

So in a holiday spirit, I’d ask: what would Eisenstein have made of this painting, which I saw again last summer in London’s National Gallery–Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity of 1501?

Reproduction, especially this tiny, doesn’t do the picture justice, but you should be able to see how the symmetry of the composition is broken by the slope up to the central scene of Mary and the mule bending over the baby. As with Swarte cityscapes, there’s a lot to dig for. Angels on left and right of the manger direct the Magi to the main action, and in the lower section angels kiss men while devils dive into the fissures of the earth.

Key for students of cinema, though, is the whirling dance of the angels in the upper third of the picture. Strictly speaking, they all seem out of step, no two in sync. But then you notice that each is executing a slightly different phase of one continuous movement, as if Muybridge had captured a single dancer’s circling trajectory with his early stop-motion photography. Angel Locomotion, he might have called it; but Botticelli got there before him.