Once more, Mad City movies

Sunday | April 15, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

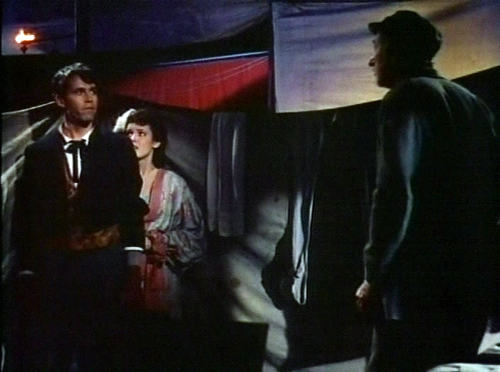

Night and the City.

DB here:

It’s been a busy time in Madison, at least for me. KT is in Egypt, peering at shards of statues and documenting earlier Armana excavations. I’m at home, having missed the Hong Kong International Film Festival (doctor’s orders) and wistfully wishing I’d been there for the tribute to Peter Chan Ho-sun (check out Fred Ambroisine’s interview at Twitchfilm) and a chance to see—Don’t say whoa!—Keanu Reeves, who was there with Side by Side, his new film on digital cinema (snif).

Instead of traveling, I’ve been doing other stuff. There were, and still are, last-minute checks and fixups on the new edition of Film Art. I went to some movies–Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, The Hunger Games, The Raid: Redemption, Carnage, 21 Jump Street—as well as screenings at our Cinematheque. Late at night I’ve been watching 1940s films for a long-range project. Most frantically, I’ve been working on a little e-book to be finished, I hope, in three weeks. It will be available on this site, ludicrously cheap, you will want one for sure, I bet, well, why not? More about it later.

In the meantime, Madison has hosted some remarkable visits. I’ve already mentioned Lynda Barry’s delightful presentation of Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. I must also mention two other dignitaries that illuminated our lives this spring.

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

More recently, we were visited by Schawn Belston, an old friend who’s Senior Vice-President of Library and Technical Services at Twentieth Century Fox. Our Cinematheque is running a string of Fox restorations, and Schawn brought along a stunning print of the lustrous noir classic Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950).

There’s a nifty story behind that print. Schawn and archivist (and Badger) Mike Pogorzelski discovered an original camera negative in the Movietone News vault in Ogdensburg, Utah. When they struck our print (directly from the neg) and showed it to Dassin a few years ago, he wept with pleasure.

Schawn found another version of unknown provenance. On the basis of the first reel, which he screened for us, this seems to be a British version, with a different voice-over narrator, varying footage and cutting patterns, and a lighter, more romantic score. As Schawn pointed out, this plays more slowly and is more of a melodrama than a thriller; it also makes the Richard Widmark character a little more sympathetic, I thought. Nobody has yet discovered why this version was made.

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

*Lots of filmmakers are still finishing on film, but the plan is to make no prints available to US theatres after 2012. About 300 prints of current titles will still be made for the world market.

*Both Fuji and Kodak are still making film stock, even new emulsions, but the decline in usage will raise prices. A 35mm print now costs $4000, a 70mm print runs $35,000 and up.

*Storage problems are immense. The studio wants to save all the raw footage; in the case of Titanic, that comes to 2.5 million feet. Which version of the film has priority for the shelf? Typically, the longest cut, often the first preview print.

*All studios are still making 35mm negatives for preservation, typically from 4K scans. Ironically, their soundtracks, usually magnetic, can’t match the uncompressed sound of the files on a Digital Cinema Package (DCP).

*”Film is the most stable medium, but the preservation practices for it are the most vulnerable.”

*Nearly all film restoration is digital now, so the best way to show the results is probably digitally. That also makes for standardized presentation and less wear and tear on physical copies.

*Most classic films in a studio library are not available on DCP. If an archive or cinematheque or theatre wants one, there are ways to make on-demand DCPs. But it’s not cheap. A 2K scan runs $40,000; a 4K scan, somewhat more. Schawn opts for 4K because a digital version should be the best possible. It might be the last chance to make one!

*Films stored on digital files must be migrated frequently. Sometimes that’s done through “robotic tape recycling.” But there are problems with the constantly changing formats and standards. The Movietone News library was originally digitized to ID-1, a high-end broadcast tape format from the mid-1990s, so that material will need to be copied to something more current.

*Schawn believes that objective criteria about color, contrast, and other properties need to be balanced with concern for the audience’s experience. By today’s standards, original copies of Gone with the Wind and The Gang’s All Here look surprisingly muted. But to audiences of the time, they probably looked splashy, because viewers saw so few color movies. Restorers and modern viewers have to recognize that perception of a film’s look is comparative, and the terms of the comparison can change.

Schawn’s point was made after his visit with our Cinematheque show of the restored copy of Chad Hanna (Henry King, 1940). For a Technicolor film, it had a surprising amount of solid black, and not just in night scenes. We’re used to “seeing into the dark” via today’s film stocks and digital video formats, and we probably identify Technicolor with the candy-box palette of MGM musicals on DVD. We sometimes forget that chiaroscuro was no less a resource of color film of the 1940s than of black-and-white shooting of the period. A leisurely, charmingly unfocused story with a radiant Linda Darnell (she lights up the dark) and Fonda at his most homespun, Chad Hanna was good in itself and an education in color style circa 1940.

Schawn’s visit, like Tony’s, was informative and plenty of fun. We want to see both again soon.

Up next, as Robert Osborne would say: Some picks for the Wisconsin Film Festival, which launches Wednesday.

Thanks to Jim Healy, Cinematheque programmer, for arranging Schawn’s visit and the Fox retrospective.

Chad Hanna. Not, emphatically not, from 35mm; from Fox Movie Channel.