A man and his Focus

Thursday | May 3, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

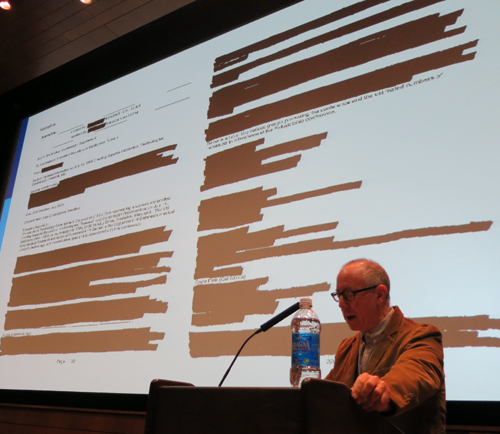

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.