How to watch an art movie, reel 1

Sunday | August 26, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Sueño y silencio (2012). Shot 1.

DB here:

We all know that Hollywood films and their counterparts elsewhere obey certain conventions of style and story. (I say conventions to put it neutrally. Some will call them formulas, some will call them clichés.) Against that tradition some critics and film lovers posit what’s been called “festival cinema” or “art cinema,” a tradition that favors individual expression and more unusual storytelling. But can we say that this tradition also has its conventions?

I think so. Let me take an example that you’ve probably not (yet) seen. Jaime Rosales’ Sueño y silencio premiered in the Directors Fortnight at Cannes this year, went into distribution in Spain recently, and will probably be making the festival rounds. I think it’s a good film, but my appraisal is beside my point today. I want to use the film as a sort of “tutor-text,” a handy way of talking about how such movies engage us in ways different from more mainstream films.

Paranorms

Central to my claim is that such films cultivate intrinsic norms, storytelling methods that are set up, almost like rules of a game, for the specific film. In a way, every film does this. I once wrote that “every film trains its spectator”–an idea that Jim Emerson put more pungently as “Any good movie–heck, even the occasional bad one–teaches you how to watch it.” Up to a point, we figure out the film’s characteristic stylistic and narrative strategies as it unrolls.

Of course most films’ intrinsic norms match what we can call extrinsic norms–those codified by the tradition. Hollywood films frequently simply follow the conventions of genre, structure, style, and theme that have flourished for a long time. What the art film does, I think, is what ambitious Hollywood films try to do: It tries to freshen up its intrinsic norms. But it does this according to broader principles of the art-film tradition. In other words, an individual device might seem strange, even unique to this or that movie, but the function it fulfills is familiar to us from our knowledge of the tradition’s conventions. We figure out the device because we assume it has a familiar function.

Take an example. How does the film indicate that certain images are flashbacks? Classical Hollywood films provided clear markers: Dissolves as transitions, wobbly music, voice-over remarks indicating that a character was recalling the past. But 1960s art films found other devices–slow-motion, shifts to black-and-white or a different palette, cuts to images that would have been out of place in a continuous scene. Viewers who understood the concept of flashback could infer that in this film, flashbacks were signaled through an unusual intrinsic norm. Fairly soon, of course, these devices were widely copied and became extrinsic norms, to the point that Hollywood films picked them up.

I’ve tried to make this entry a primer in art-cinema comprehension strategies. Many of this site’s readers have had a lot of practice in watching films like Sueño y silencio, so in a way what I say won’t come as a surprise. Yet many skilled viewers know the conventions only tacitly. Critics are well-versed in the tradition, but they typically talk only about the film at hand and don’t examine how it connects with more general principles of storytelling. Noting these guidelines, then, helps us understand criticism as well as movies; we can gauge critics’ reactions more exactly when we realize they’re responding to particular conventions.

Since Sueño y silencio has had such limited exposure, I’ll dwell only on the film’s first twenty minutes, its first reel. If you don’t want any spoilage at all, stop reading right now. But actually, my commentary tells you less about the film’s plot twists than the early reviews. I’m just trying to illuminate how such films work and, of course, entice you to see the film if it becomes available to you.

Fifteen shots

When we go to a movie we usually know a good deal about it. For now, though, let’s pretend you haven’t been privy to any information about what you’re going to see in Sueño y silencio. You just take it as it comes. But of course you’re exercising your eyes, ears, and mind all the while.

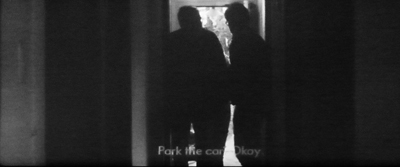

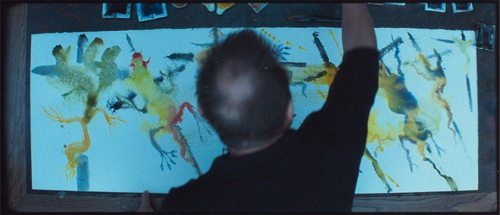

First you see a water-color painting being finished, in fast motion, by an unidentified painter (see the still at top). The image is pretty hard to determine. What seems to take shape is an image of a vaguely simian creature on the left, some animals in the middle, and a humanoid slung on what looks like a spit. What can this image have to do with what follows? Is the painter our protagonist, and will we learn about his creative endeavors? No. The shot functions as a kind of narrational mystery: We ask not only what it signifies, but why we’re being shown it.

This is as good a way as any of formulating an initial guideline for the hardcore art movie: How the story is presented is as important as what is presented. For instance, is this image offering a cluster of motifs that will be important in the film? When the film is over, we might be able to find out something about the painting or the painter, and we might find some connections to the plot.

So a second guideline: Often we’ll have to go outside the film to understand its story. This contrasts with most mainstream movies, which don’t make reference to recondite things like Spanish abstract painters. As it turns out, the painting refers to Abraham’s pious willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac to God, but it treats the tale in a disturbingly primal way.

Now the story proper seems to be starting. We watch a woman putting on eye make-up, seen through a slit in a door. There’s no dialogue, and the camera waits patiently; the shot lasts nearly a minute. This is the first signal that the film will be observing everyday routine, in more or less real time, from a stationary standpoint. The intrinsic norm that shapes nearly all the film–one fixed shot per scene–is being put into place. This stylistic choice isn’t unique to this film, but it is characteristic of art cinema. When there aren’t dramatic goings-on, as with Paranormal Activity‘s locked-down surveillance camera, the static shot usually asks us to adjust our expectations to a slowly unfolding exposition.

Why start with this woman (whom we’ll learn is called Yolanda)? I think it’s because, as the film goes on, she will be the focus of most of our attention, particularly once the drama starts. In a way, the film is following a very common extrinsic norm: Identify your protagonist early.

But the director gives with one hand and takes away with another. Yolanda isn’t doing anything of particular dramatic significance. At the same time, Rosales conjures up another, more unusual norm: obscured vision. We don’t see Yolanda fully and adequately. Throughout the film, our knowledge of what the characters do, even what they look like, will be cramped by such stylistic decisions. The film resists quick and easy comprehension; it asks us to make some effort. A new guidelines suggests itself: Be prepared to fill in a lot. And expect occasionally to be wrong.

A man (later identified as Oriol) and a little girl (Celia) are reading a storybook together. The tale is about monkeys in a park, and one escapes (in a book illustration they describe). Maybe this monkey connects back to the simian creature we saw in the painting? Later in the film, a zoo and a park will become very important.

But before we even get to these motifs, we notice that the filmmaker isn’t telling us who these characters are, or what their connection is to the woman we saw in the previous shot. We might assume that they’re a family, but a Hollywood film would tell us clearly and quickly (“Hi, Mom!” “Hi, honey. What are you and Dad reading?”). Here we have merely a possibility. A new guideline: A lot of exposition can be left to the imagination.

We’re also invited to consider the possibility that Oriol and Celia are especially close, since the other daughter we’ll meet, Alba, isn’t in this scene.

A long shot in a clothing store lingers for a while before Yolanda and two girls drift in from the right and wander to frame left. They are browsing for an outfit for Celia. Yolanda suggests a couple of choices, but Celia rejects them as uncool. Now we have better reason to take Yolanda as the mother of the family, but given that Oriol isn’t shopping along with them, there’s always the possibility that the parents are divorced or separated, swapping the kids back and forth. The basic circumstances of the family are held in suspension for some time.

The empty frame that opens this shot suggests another guideline. In many art films, settings take on a weight that they don’t have in many mainstream films. We’re used to them as a more or less neutral container for the real action, the clash of characters pursuing their goals. Films like Sueño y silencio may contain moments that function like the descriptive passages in a novel. These blocks of space invite us to focus on surroundings–to see them as abstract designs (planimetric framings like this work well), or to recognize their concrete layout, as here when Yolanda and her daughters have to thread their way through the aisles. Just as the unmoving long take asks us to feel the pressure of time, we should be ready to register space as space.

The next shot, of Oriol at his desk in his office, is doubly obscure: He’s in silhouette, and he’s talking to a man who is offscreen. This introduces another norm of the film: Often we won’t see both partners in a conversation. The framing will usually concentrate on the family members, as if the secondary characters are really secondary. But there are exceptions, and surprises as well.

The offscreen man is discussing his career, and from the conversation we learn that Oriol is an architect. But by starting with his role as father (reading to Celia), the film invites us to infer that the family may count more for him than his job does. (Imagine if the plot began by showing him at work, then showed him at home.) And just as he was patient and calm with Celia, he’s the same way with the young man offscreen.

In other words, first impressions matter in all films. They provide an anchoring bias that later developments will be measured against. In fact, an extended crisis later will propel Oriol into his work and away from his family. So while mainstream films tend to reinforce first impressions, many art films will nuance or even negate them. This can create an impression of character complexity, or of a narration that doesn’t pretend to know everything about the story.

Six and a half minutes in, the narration breaks one of its “rules.” A smoothly tracking camera takes us through a building under construction. For a few moments we’re allowed to register this as a specific place before the camera halts on a distant view of Oriol and some colleagues discussing the construction project.

In story terms, this could seem pretty redundant; we know Oriol is an architect. (Okay, now we know he’s a hands-on architect, but still…) But I think that the shot is important as resetting the film’s intrinsic norms. Later in the film, we’ll get small doses of camera movements of different types (one lateral track, one handheld shot, a couple of gliding Steadicam moves). It’s almost as if Rosales is sparingly spreading several alternatives out alongside his procession of static shots–a creative choice that will continue to dominate the film.

On the second viewing, it seemed to me that the payoff of this loft shot occurs when the camera moves away from the men and back toward the windows. Bursts of flash frames, as if the film were inadvertently exposed, end the sequence.

At the plot’s first turning point, we’ll get another moving shot, with the camera mounted on a car, and that will be broken up by a fusillade of flash frames like these. We’re used to foreshadowing in plot terms: the gun in the drawer in act one will get used at the climax. But we should expect that art films will use stylistic foreshadowing, often in place of the dramatic sort.

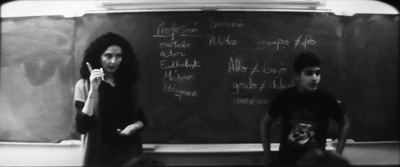

Now the exposition, oblique though it is, starts to hang together. Scenes of the family together (shots 2-4) are followed by a pair of shots showing Oriol at work (5 and 6). In another planimetric shot we see Yolanda at work, teaching Spanish to French students. But so far no conventional drama has started. Rosales has concentrated on showing the family’s daily lives and then lets us infer relationships and character from lots of ordinary activity. In shot 5, Oriol speaks as an idealist, saying that a building project’s budget ought not to determine the result. Here Yolanda is patient with her (unseen) students as she teaches them vocabulary through a guessing game.

For the Hollywood screenwriter, character is ultimately revealed through conflict. In many art films, character is revealed–or kept under wraps–through routines. This strategy puts an emphasis on what the person is like when not grappling with problems–on what we might call their enduring natures, or (as in Bresson) on their essential mystery.

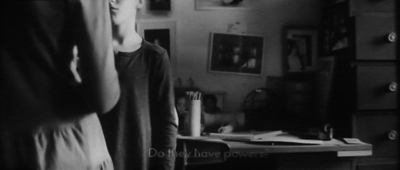

More empty space: A girl’s bedroom, with photos and projects and lots of colored pencils and pens. Audrey Hepburn looks out at us. As in the clothing shop, setting comes forward. This time the locale encourages us to make inferences about character: later we’ll learn that Alba likes to draw and paint.

And more indirection. Offscreen conversation between the girls is followed by the two of them stepping partially into the frame. By now we can see that this film will deny us a lot. What will it give in return? Emotion–a domestic tragedy is going to strike–but muted emotion.

The girls play together, but it’s their gestures and voices (talking about a game they’ll play) rather than their faces that we have to fasten on. Art-cinema narration is a lot like what we find in a mystery film, but we’re teased with clues about basic story action. Instead of who done it? we ask what are they doing?

Now the scenic norm is firmly in place: We’ll be lucky to get half the scene: one character, or offscreen sound, or partial framings. In the ninth shot, all we see of Oriol is his arm. Still, maybe at last a drama is getting going. The boss complains that Oriol commits the firm to projects and then, once it’s on the hook, everybody has to fulfill his plans, regardless of the cost. Oriol replies that he’s flexible and willing to have the overages deducted from his pay. This leaves the boss flummoxed.

Yet this isn’t the core of the plot; nothing comes of the boss’s exasperation. An art film may give us nascent conflicts but never develop them, or pay them off. Characters may come and go without preparation, and chance events may divert the plot. Are these tactics more realistic than what we get in tightly plotted films? Some would say so; they’d say it’s more like the way life moves. In any event, it’s an important convention of this filmmaking tradition.

Parallels matter more than causality in many art films. While Oriol confronts job problems, Yolanda chats with other teachers. They consider the fact that kids don’t like foods that they’ll enjoy when they grow up. She suggests adding some chorizo to lentils, accentuating her as a Spaniard teaching in Paris.

Again a routine is invoked, but now we get a good look at the woman we’ll be seeing a lot of. Unlike the distant shots we’ve had so far, this shows us her curly hair, sharp chin, and gleaming eyes. The gentle, easygoing nature she revealed in shot 7 is confirmed. The film is introducing us to her very gradually, again through routines.

A variant of shot 3 (but Dad now with both daughters) and shot 4 (both daughters with Mom). The girls are waiting for their music teacher and Oriol keeps them amused. His closeness to them is reiterated, so that later when he changes his attitude, that becomes more marked.

Again the emphasis falls on everyday “undramatic” activities. Rosales is really pushing his luck. “For a long time,” wrote one critic, “nothing much is happening and the feeling of directorial self-indulgence is tangible.” Actually, we’re only fifteen minutes into the film at the end of this shot. Patience, please.

Some would say that the movie could begin here; many movies would. The parents are together in bed (so it’s presumably not a split-up family) and sharing time with the kids. They’re telling each daughter how she was born. One came out yelling, the other as if swimming.

Again, though, it’s all in the staging. We scarcely ever glimpse the daughters’ faces, and at many moments, as in my frame here, the parents are blocked by the kids. Like the slit composition in shot 2, the silhouette of shot 5, and the distant framing of shots 4, 6b, and 11, this shot gives us a willfully stingy stream of information. But the presentation is consistent with the staging and framing that contribute to the film’s intrinsic norm, so we’re not as startled by this shot as we might be if it cropped up in an ordinary film. It also varies the norm: Now characters don’t have to be off frame to be invisible.

Some critics would be inclined to say that this shot, like others “distances” us from the characters and their situation. But we shouldn’t confuse pictorial distance with emotional distance. Long shots can be emotionally wrenching; just look at the last two shots of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. I’d prefer to say that in what could have been a sentimental scene, the composition and the actors’ understated playing keeps the emotion simple and understated.

This is the first time we see the whole family together. It’s also the last. Some art films are quite laconic.

Laconic, did I say? Cut to a rocky landscape and the sound of a car engine. Is a car visible in the shot? Two screenings in 35mm didn’t reveal it to me. Again we’re invited to suspend our narrative interest and study a space.

Soon we’ll learn that this shot stands in for the travel to visit the grandparents. The bed scene makes no mention of the upcoming trip, so this landscape comes as a surprise. The moment reminds us that the film lacks cohesion devices, those elements that tie scenes together through:

Plans: For instance, maybe “Tomorrow you get to go see Grandma and Grandpa!”

Appointments: “Don’t forget you have to get up early for the trip!”

Deadlines: “Oriol, can you make it there before nightfall?”

Hooks: Those lines of dialogue that link the end of one scene with the beginning of another :”Don’t you love that wrinkled terrain near where your father and mother live?”/ cut to landscape.

Mainstream plotting tries to bind one scene to another tightly, making their succession seem smooth and inevitable. We’ve become so used to this that many art films feel fragmentary. We can’t easily predict what we’ll see next. After all the images of people, Rosales’ “empty” shot is surprising.

This refusal of tight scene-to-scene connections creates a different sense of time and forward-moving action. Movies like Sueño y silencio present life as one damn thing after another, not necessarily one damn thing because of another.

In laying out those possible transitions, I just construed shot 13 retrospectively, knowing what came next. The action’s causality has to be figured out afterward; we often have to think to understand what we’ve just seen. This is one of many reasons that we must often watch such movies twice (or more) to appreciate them fully.

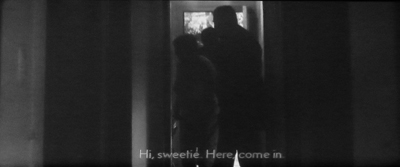

Now more opaque/oblique presentation. An old man comes through a doorway, illuminated briefly.

As the old man becomes a silhouette, another silhouette emerges. It must be Oriol, by his voice and his glasses, but we have to pay attention to be sure. Is Yolanda there too? And the daughters?

the even more obscure figure of a woman comes bustling in from the right and starts speaking to someone in the adjacent room. “Hi, sweetie!” Our inference engines have to work up exposition again. Older couple: probably grandparents. Grandma doting on (unseen) granddaughter. But only one daughter? And no Yolanda?

Yes, only one daughter came. “One is better than none,” Grandma says as she leads the girl–on a big screen, you can make out that it’s Celia–to the foreground and out right. And no sign of Yolanda, so we must infer that Oriol made the trip only with the one daughter Celia. Hollywood tends to tell you important story points three times; art movies, less often. It’s the mystery-story model again: basic information is given through clues and hints.

Finally, delivering on the early line of dialogue in which Oriol says he’ll move the car, the camera dwells on the corridor. Then we see the car backing up. Ending with the distant doorway we saw at the start, the shot is given a neat curve of development.

It would have been much simpler to show an exterior long shot of the house, the old folks coming out toward the camera to greet the car as it pulls up, Oriol and Celia climbing out, hugs all around, and so on. But then we wouldn’t have been as actively engaged in the way the scene develops; we’d immediately label it “Family visit.”

One way to think of art-movie conventions is that they’re reworking of elementary story actions we’ve seen before, but transformed through choices about narration (suppress some information) and visual and auditory style (choose an elliptical or “difficult” way of shooting the action). I think this tendency is one reason some critics think that such films heighten our awareness of both ordinary life and the conventions of art. “The Dream and the Silence,” says one, “is the work of someone with enormous intelligence and a need to see the world afresh.”

Surely not every viewer will grasp the points I just made. (I didn’t myself on the first viewing.) Any artwork needs some redundancy, so the next shot/ scene stabilizes our understanding of the situation. It’s now clear that Celia and her father have come for a holiday. She goes walking in the forest with her grandmother, who explains about grasses and trees on their property. They wander out of the frame, and the camera drifts away from them. Their conversation fades out, and the camera continues its trajectory….

…until it stops at a dark mass of bushes. Why?

I wish I could answer with confidence. The camera movement is a complement to the forward tracking we saw in the construction site during shot 6, but that’s not enough to explain the strong emphasis given to this foliage. Is it meant to evoke the rough, Art-Brut look of the painting in shot 1? Given what comes in the next five minutes, are these brambles a premonition of catastrophe?

In a way, the shot brings us back to the watercolor painting of the opening. In films like this, there will always be some images, sounds, or scenes that resist easy sense-making. They become interpretive nodes for critics to probe, sometimes for years.

These fifteen shots constitute the film’s first reel, and they lock in place many of the intrinsic norms. But these norms won’t simply be repeated in the course of what follows. They will be varied in cunning ways. The omission of certain information will keep us in suspense, heightened by framing that excludes what we need to know. After we’ve become used to the norm of the offscreen speaker or listener, one later shot will use it surprisingly, with disquieting emotional effect. After shots in black-and-white, two are in color. After the rigorous objectivity of what we’ve seen so far, we’re surprised to see a shot that is likely to be a hallucination. And the film’s one optical POV passage will be decoupled from its owner, in both time and space.

The variations keep us engaged in the ongoing effort to assemble a coherent story, with each scene forcing us to rethink the one that it replaced while sensing the emotional currents at play within both of them. In Sueño y silencio, the conventions of art cinema allow Rosales to present profound pain with a measure of tranquility. We can register this mixed emotion all more acutely because we’ve participated in creating it. We grasp the conventions he’s exploiting, and we can enjoy seeing them employed in fresh ways.

There are several scenes from Sueño y silencio on YouTube, but I wouldn’t necessarily suggest watching them. They’re pretty meaningless out of context. See this review for a little background on the making of the film. Rosales claims that he used nonactors and let them improvise their scenes.

The ideas in this entry are reworkings of points I’ve made elsewhere, notably in Narration in the Fiction Film and in the essay “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” If you’re interested in that essay, I’d prefer you read the revised version in Poetics of Cinema. On this site, another analysis of intrinsic norms in an art film is the entry on the excellent In the City of Sylvia.

I’m grateful to Cinédecouvertes, the annual festival conducted by the Cinematek of Brussels, and specifically to Sam DeWilde for bringing Sueno y silencio. Thanks also to Clémentine De Blieck for technical assistance and to Gabrielle Claes for enlightening conversation about the film.

Sueno y silencio: Miquel Barceló paints “El sacrificio de Cristo.”