Sweet 16

Monday | March 4, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

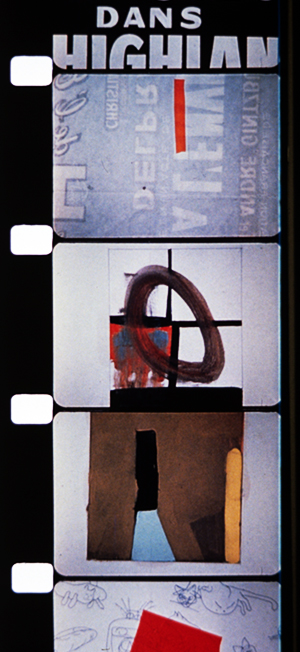

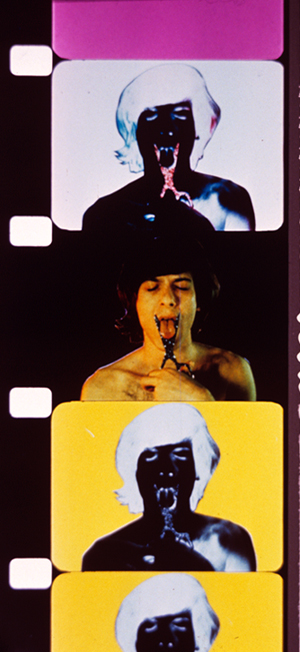

REcreation (Robert Breer, 1956); T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G (Paul Sharits, 1969).

DB here:

Snows and thaws and refreezing, amplified by a torrential rain, gave water a new path into our basement. We’ve spent about two weeks emptying bookshelves, drying them out, and shifting books to other places. No volumes were damaged, but we had to make space in the dry areas for the migrant titles.

That meant facing up to the problem of 16mm.

The solution was drastic.

Narrow-gauge movies

My film collecting started with 8mm. Not super-8; that was invented later. (Imagine how old I am.) I made my own movies in 8, but I also bought, from the venerable Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, copies of films in that format. Most memorable was the Odessa Steps reel from Battleship Potemkin, which I projected often on my bedroom wall.

Not until I went to college and joined a film club did I lay my hands on 16mm. I suppose if you start out handling 35mm, 16 looks skinny and 8 looks like a toy. But moving from 8 to 16, I could see only improvement. You could, with the sharp eyes of the teenage geek, actually see the image on the strip. I projected many films on our JAN surplus projectors, and one weekend I hauled a print of Citizen Kane to my apartment to watch several times. Do I need to add that all this was in the 1960s, long before films became available on videotape?

Arriving in Madison in 1973, Kristin and I bought a Kodak Pageant, the 16mm workhorse. Not as good as a Bell & Howell, most aficionados would tell you, but fairly cheap and easy to handle. When we moved from apartment to apartment, the Pageant went with us.

In 1977 we bought a house, and I set up a jerry-rigged projection room in the unfinished basement. In our second house, where we still live, I was able to set up something more permanent. Now there were two projectors encased in a booth and mounted on a platform.

We spent many hours watching movies in that currently soggy basement, with its burgundy carpet and dark wood paneling. Although the room lacked the comforts of what we think of as a home theatre, we sometimes screened things for big groups, either a party or once in a while students in a seminar.

In both venues, we previewed movies we were showing in courses and revisited some of our growing collection: The Shop Around the Corner, High and Low, True Stories (must blog about that some time), You Only Live Once, and so on. I’ve already expounded on the key role of His Girl Friday in our mini-cinémathèque.

By then Kristin and I had also started working with 35mm prints in archives and with 35mm trailers we scavenged to make slides for lectures. For a brief while we even had 35mm in our screening space, but with only one projector, shows stretched too long. Although home video had taken off, Betavision, VHS, and even laserdiscs couldn’t compare to a good 16 copy. We continued to collect and show on film, as did our department.

In the last decade, improvements in digital projection, along with the arrival of Blu-ray, led to the decline of 16 in our local media ecosystem. Our department still shows a lot of 35, but 16 seems mostly the province of our experimental and documentary courses. As for us, we hadn’t screened 16 at home for some years. Then came the February leak, and we had to face the problem.

We’d already given many of our 16mm titles to the department, keeping our most fond treasures at home, thinking we’d watch them some day. Now we needed the space that those cans and cases occupied. Anyhow, it was probably time to let go. So we decided to surrender the features, the shorts, the cartoons, the splicers and the rewinds and the six Pageants—everything.

Our house is a museum of defunct technology. Just recently I surrendered my lovely Teac reel-to-reel tape recorder. Packed away are hundreds of Beta and VHS tapes. On groaning shelves sit hundreds of laserdiscs, mostly Asian. Yet under a roof that houses no fewer than six laserdisc players, there is no trace of the predominant nontheatrical film format of the twentieth century.

FOOFs

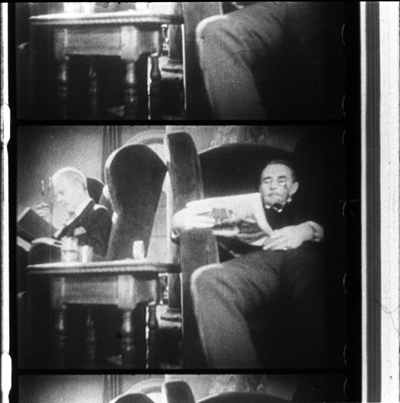

Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966).

Nowadays it’s easy to own a “film”—or rather a disc or file or stream of pixels fed to your display. (Though I wonder what it means to “own” something sitting on the Cloud in your virtual locker.) Back in the day, joining the ranks of 16mm collectors meant a real commitment. You needed to buy gear, you needed to clean and inspect the films, and you needed to learn a little projector maintenance. You probably subscribed to The Big Reel and Classic Film Collector, tabloids that ran ads selling or swapping prints and equipment. And you usually went to film collectors’ conventions, jamborees of selling, trading, and movie watching. The three biggest events, Cinecon (Los Angeles), Cinefest (Syracuse), and Cinevent (Columbus, Ohio), brought together the overwhelmingly male tribe of FOOFs: Fans of Old Films.

FOOF collectors had good hunting in those days. There were plenty of 16mm prints floating around, but quality varied. The best were those cast off from legit distributors. Made from internegatives drawn from 35mm positives, they usually had good tonal values. At the other end of the scale were the dupes, copies pulled from 16mm distribution prints. These ranged from acceptable to awful; but if you wanted a rarity, you might have to spring for a dupe.

In the middle zone were TV prints, probably the majority of copies in circulation. When studios licensed their pre-1948 libraries to television, go-between companies like C & C put together packages of prints to be sold to local stations around America. Small stations in the hinterlands harbored scores of 16mm copies, to be trimmed, filled out with commercials, and broadcast outside prime time, and sometimes within it as “Million Dollar Movie” or whatever. It’s still not fully appreciated, I think, how many baby-boomer auteurists around the country caught classics in the pre-dawn hours on local television.

But as network and syndicated programming expanded, there was less room for old movies. Why run a 1936 Paramount picture when you could show color re-runs of Bewitched or The Six Million Dollar Man? The stations’ 16mm prints were headed for landfill when enterprising collectors and entrepreneurs salvaged them. You could tell when you got a TV print. It might carry a packager’s logo; it would have low contrast; and splices between scenes would signal where the commercials had been jammed in.

FOOFs had their demons and demigods. Principal among the demons was one colorful character, who had the habit of bothering collectors circulating versions of old classics to which he claimed current rights. In The Sneeze, FOOFs made fun of the man who, releasing recovered prints of Birth of a Nation and Keaton films, made sure his own name featured prominently in the credits.

Among the demigods were Kevin Brownlow, he who had rescued Napoleon, and David Shepard, who started out at Blackhawk and eventually founded Film Preservation Associates. Most legendary of collectors was William K. Everson, who died in 1996. Thousands of prints were squeezed into his two Manhattan apartments and spilled over into the storage areas of NYU’s film department. He acquired many of his films in exchange for services he rendered to Hollywood studios. His gems were screened in his courses, in sessions of the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, and in lectures he presented around the world. I remember his excellent presentation on Joseph H. Lewis at Chicago’s Art Institute Film Center, where he showed clips from Lewis’ Poverty Row productions and even some credit sequences Lewis had crafted.

Bill brought a magnificent selection of titles to Madison in the early 80s, and many of them, such as Bulldog Drummond (1929) and Justin de Marseille (1935), remain rarities. Generous beyond measure, he also let NYU faculty and students borrow his movies. When Annette Michelson needed to see East of Borneo (1931) for her essay on Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), she turned to Bill. All of this largesse was made possible by the portable, user-friendly format of 16mm.

Freezing the frame

Teachers, filmmakers, and collectors had a special relation to 16mm. In addition, as researchers, we developed an unusually intimate rapport with the format. When I started teaching, I felt the need to illustrate my lectures with images from the films. My first efforts involved setting up a 35mm still camera on a tripod and photographing from the screen. If the projector could stop on a frame, so much the better; but even if not, you might snag an acceptable shot. The projected image would be surrounded by darkness. Today I wince at the results, as with this shot from Crime of M. Lange, one of the few old slides we haven’t cast out.

You could get sharper slides with a gadget called a Duplicon, but it cropped the 4 x 3 image to something like 3 x 2.

When Kristin and I decided to write Film Art: An Introduction, the few introductory textbooks relied almost entirely on production stills, those images shot on the set and circulated to promote the film. The Museum of Modern Art had an archive of production stills, and then as now, publishers turned to such collections for illustrations. As part of the first generation of university-trained film researchers, we doggedly insisted that all our examples would be actual film frames.

Today, digital video has made grabbing frames easy. But before the late 1990s, it was hard. Videotape frames looked terrible, as some books from the 1980s attest. To get decent quality, you needed access to prints. You needed a way to put a reel onto rewinds or, ideally, a flatbed editor like a Steenbeck. And you needed a camera with an enlarging attachment. When you’d copied your frames, you took the exposed film to a lab, where you hoped for a passable result. Black-and-white shots were easier than color, which required blinding lamps of a color temperature matched to Ektachrome or Fujichrome or Agfachrome.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

But most of the films we wanted to illustrate we could find only on 16. We rented prints and then took stills on a rickety gadget built for us by our friend David Allen. David bolted a pair of rewinds to a plank of plywood. That plank rested on a little table. Into the plank was cut a square slot for an upright light box. The box contained a bulb and was surmounted by a square of translucent plexiglass. The bulb could be put at the bottom of the box, for a photoflood lamp, or near the top with a cooler and dimmer appliance bulb for black-and-white. You positioned the film on the plexiglass and aimed the camera down at the film. A crude zoom lens allowed us to photograph a couple of frames of 16mm and one of 35.

We took the light box on our travels. Archivists certainly looked at us oddly when we brought the thing in, but they usually gave us permission to use it. We’d watch the film on a flatbed and bring the light box over alongside it. Laying the film gently on the surface, we’d poise the camera above it.

Here’s an example of what we got with our plywood setup, from Bill Everson’s print of Bulldog Drummond.

Over the years we improved our system. We bought better cameras, with sharper lenses. We found purpose-built attachments that hold the film strip firmly in place. (Alas, Canon and Nikon seem to have discontinued these rigs.) We used smaller lighting units rather than our curious box. For the last few decades we’ve shot horizontally rather than vertically.

Even in this age of video grabs, we make many frame enlargements on analog stock with 35mm cameras. Even if a film is available on DVD, some of the things we study aren’t preserved in that format. Of course many films aren’t available on video at all, and a great many of those were made to be seen on 16mm.

Format churn catches up with us

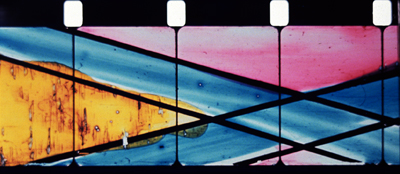

Notebook (Marie Menken, 1962).

Super-16 lives as a production format, but its older brother is nearly dead. True, a few die-hards like Ben Rivers continue to shoot on 16mm, but its future is mostly all used up. James Benning could make 16mm look like 35; when I asked him how he did it, he answered: “I use a light meter.” But even Jim has switched to digital. As for projection, many colleges and art centers have pitched out their 16 equipment.

Since our earliest editions, Film Art included discussions of two remarkable films: Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) and Robert Breer’s Fuji (1974). These have not been, and might never be, released on digital disc. Yet by the end of the 2000s, we found that virtually none of the users of our book screened these films for their classes, and curious readers without access to 16mm projection couldn’t easily see them. Reluctantly we cut them from the tenth edition of last year. We replaced A Movie with Koyanisqaatsi to illustrate associational form, and Fuji was replaced by Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as an instance of experimental animation. Both titles are available on DVD.

Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to revive our original discussions of the Conner and Breer films on our site here. We hope that will help the few loyal chevaliers who told me that they did indeed use the films in their courses. But our choice points up a larger problem.

So many documentary and avant-garde films were made and circulated on 16mm that we are at risk of losing a very large slice of film history. We’re lucky to have some Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton films on DVD, but what about all the other titles that were distributed by Canyon Cinema, the Film-Makers’ Coop, and other groups? We can get DVDs of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, and some classic ones have been made available on archival collections; but there are many more that depended on 16mm platforms. Even bigger is the set of everyday 16mm movies: amateur films, home movies, and hundreds of miles of newsfilm, from both big TV networks and local affiliates. A great many of the “orphan films” championed by Dan Streible and his colleagues are in this narrow-gauge format.

Recall too that the films of those animators and experimentalists who work frame by frame, such as Breer and Paul Sharits and Paolo Gioli, cannot be studied closely on DVD. How could DVD reveal to us the nifty paintwork of Marie Menken’s Notebook? For that you need a light table, or someone able to photograph it and show you.

Archives will retain 16mm projectors and viewing tables as long as they can. They will preserve prints, perhaps migrating the most sought-after ones to digital formats. Passionate collectors like Tim Romano, who zealously pursues lost films and then donates them to the AFI, will find a way to use our cast-off gear. Our Film Studies department will hang onto the format until the last aperture plate cracks.

16mm was so much a part of our work, our play, our education—in short, our lives—that the separation was inevitably poignant. Pinned to the bulletin board in my basement booth was Ellen Levy’s poem, “Rec Room.” It is, I think, about the fragility and faultiness of the 16mm image, as made palpable in home screenings, and about how that fragility nonetheless carries a pulse of vitality. It begins:

The film assumes the texture of its screen

on the first projection. Audrey Hepburn’s face

creases where the rec room paneling once

took exception to it for the sake of

rephrasing it slightly—a lesson

these late viewings have brought home. Home

screen or revival house . . . .

Thanks to Erik Gunneson and Tim Romano for helping us recycle our 16mm stuff.

Media historian Eric Hoyt, in our Communication Arts Department, studies among other things how the American studios disposed of their film libraries. He talks about his research and his book project, Hollywood Vault, here.

The FOOF contingent was unequivocally a force for good. To sample some of its wonkish hijinks, watch Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates.

New York University’s Cinema Studies Department has created an extensive online collection of William K. Everson materials. For more on Bulldog Drummond, see this entry and this essay on the great William Cameron Menzies. Annette Michelson’s essay on Joseph Cornell, “Rose Hobart and Monsier Phot: Early Films from Utopia Parkway,” was published in Artforum 11 (June 1973), 47-57.

Bonded Storage in Fort Lee is part of the history of American cinema, as this article shows.

Paradoxically, you can study films frame by original frame on some laserdiscs, and on VHS tapes too if you are aware of the 3:2 pulldown. See my entry here. As so often happens, progress along one dimension means regression on another. So I cling to my rotting laserdiscs and demagnetizing old tapes.

James Benning discusses how digital cinema changed his artistic practice at Bombsite. An earlier entry of ours showcases the efforts of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to preserve experimental cinema.

Ellen Levy’s fine “Rec Room” is available in its entirety in The New York Review of Books (9 October 1986).

To watch a video about our Film Studies program, go here.