On the more or less plausible sneakiness of one Preston Sturges

Monday | May 27, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

DB here:

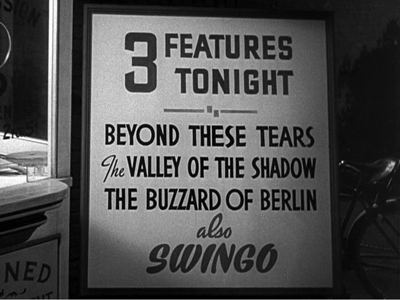

It’s no news that Preston Sturges occasionally mocked the film industry. Exhibit A is Sullivan’s Travels (1941), in which a director of escapist comedies decides to switch to serious social commentary. Sturges’ movie starts with a parody of a violent Hollywood climax that ends with two men plunging to their death. Next we’re told that Sullivan’s previous triumphs are Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft, Ants in Your Plants of 1939, and So Long, Sarong. At a later point we see a somewhat more somber triple feature:

“Swingo” is Sturges’ equivalent of Screeno and other 1930s Bingo-like games designed to lure audiences into theatres.

These gags are pretty straightforward. While working on my book on Hollywood in the 1940s, I found that The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) offers us something less obvious and more peculiar.

Three big fake features

Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) has taken Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) out on a date. They’ve told her highly combustible father (William Demarest) they’re going to the movies. Actually her plan is to sneak away and celebrate with soldiers about to be sent overseas. She convinces Norval to cover for her and to loan her his car. Trudy is gone all night. Drunk, pregnant, and now married to an elusive Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, she drives up to find Norval sleeping curled up in the foyer of the movie house. In the two scenes around the Morgan’s Creek Regent theatre, Sturges wedges in some barely noticeable jabs and in-jokes.

Start with what’s playing. Four posters are in the foyer around the box office. One is sitting on an easel turned largely away from us. The other three are mostly blocked by actors, partially framed, or thrown out of focus. But by freezing the film we can make out the titles of these three fakes.

The most visible film is Chaos over Taos, clearly a Paramount release.

You can also make out The Private and the Public, which also bears the Paramount logo. Its poster is behind Norval. Much harder to discern is the title of the third feature on the program, Maggie of the Marines. It’s barely visible for a few frames, glimpsed over Trudy’s right shoulder.

Knowing Sturges’ penchant for playfulness, we can see two of these as parodies of Paramount releases. The Private and the Public seems clearly a reference to The Major and the Minor, directed by Billy Wilder and released in early fall of 1942. Sturges began shooting Morgan’s Creek in October of that year and finished in early 1943, so he would have been well aware of the Wilder film. As an extra fillip, the star of The Private and the Public is listed as Fred McMany, a reference to Paramount star Fred MacMurray.

Then there’s Chaos over Taos. The title is weird enough, relying on an eye-rhyme and being so tough to pronounce that no studio would ever choose it. The star names, Armando Torez and Maria Robles, don’t suggest any Paramount contract players to me, but this was the period when Hispanic and Latino stars began to headline Hollywood movies: Carmen Miranda, Lupé Velez, and Cesar Romero are the most famous. Emphasizing Latin American plots, players, and locations was part of Hollywood’s contribution to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. The effort was seen most famously in Disney’s wonderful Saludos Amigos cartoon (1942) but also in a series of Fox musicals with cities named in the titles (Down Argentine Way, That Night in Rio, Week-end in Havana). Chaos over Taos could be Sturges’ dig at a then-current trend in political correctness and at another studio’s production cycle. As for the genre, Chaos/Taos is a flyboy movie and Paramount made several of those—three B-films in 1941 alone (Flying Blind, Forced Landing, and Power Dive, all featuring Richard Arlen).

What then of Maggie of the Marines? It’s likely that Sturges grabbed the title from an October 1942 news story about a dog that wandered into a marine camp in the Panama Canal. Details are at the bottom of today’s entry. We can imagine the sort of heart-warming comedy it might have been, as long as Sturges wasn’t at the helm.

Etc., etc., and etc.

Finally, there’s a matter of exhibition. Just as in Sullivan, the theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek proclaims a very long show: “3 Big Features Tonight, Short Subjects, Newsreel, and Boxo” (another mockery of Screeno). Norval tells Trudy that the whole shebang is scheduled to end at about 1:10.

Unlike the bill of fare in Sullivan’s Travels, the long show at Morgan’s Creek motivates plot action. Trudy uses the pretext of a long triple feature to get her father’s permission to stay out late. But it may not be too much to see in Sturges’ interest in triple features another contemporary reference.

Triple features emerged in the mid-1930s, partly because of high output from the studios and partly because of competition among exhibitors. Dan Goldberg wrote in Variety in 1938:

In a wild scramble for immediate returns without any thought to the outcome, the exhibitors have tried freaks and stunts rather than policy and operation. There have been double features, triple features, bank nite, screeno, keeno, bingo, and giveaways of all kinds, including dishes, flatware, linenware, framed pictures, wall plaques, etc., etc., and etc. There are many houses around here [Chicago] which are getting a 15c and 20c admission and giving away merchandise valued at 11c and more.

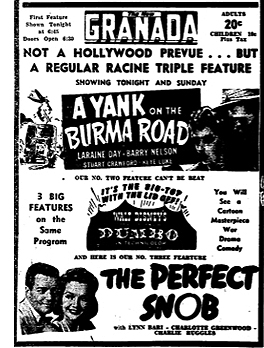

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

Triples were evidently less popular with audiences than duals. Perhaps people weren’t willing to spare such a big block of time, or they suspected that the lesser items on the bill weren’t worth watching. Jeff Smith suggests to me that adding a B to an A looks like a bonus, but two or three Bs look like a dumping ground. Interestingly, when Trudy tells Norval she plans to skip out on him, he protests: “I won’t do it! I won’t sit through three features all by myself.” Trudy asks plaintively: “Couldn’t you sleep through a couple of ’em?”

While Sturges was preparing Morgan’s Creek, he might well have noticed some Variety stories tracing a controversy about triple bills in the Midwest. A chain in St. Louis had shifted to this policy, and to retaliate a rival chain began four-hour shows consisting of two features and sixty minutes of shorts. In late 1940, a civic group, the Better Films Council of Greater St. Louis, put pressure on exhibitors to oppose long programs. The Council claimed that such bills were “a physical and mental strain on children and young people,” and that family-appropriate films were sometimes accompanied by “adult” ones. Getting no cooperation from the theatre circuits, the Better Film Council announced in early 1941 that it was going to introduce state legislation to ban triple features. This effort evidently came to nothing.

As if in response to bluenose worries about long programs, Sturges gives the lucky Morgan’s Creek patrons a movie banquet that ends in the wee hours. And ironically, Trudy would have suffered less “physical and mental strain” in the days and weeks thereafter if she’d gone to the movies and not kissed the boys goodbye. The Regent’s absurdly inflated program may be Sturges’ dig at both a contemporary trend and those who fretted about it.

Watching me rake these apparently innocuous frames, you may be asking: Is David going all Room-237 on us? Actually, I see today’s entry as in the spirit of an earlier one, which also has an enigmatic Sturges connection. I’m interested in the moments when Hollywood is talking to itself.

We tend to think that the studios made movies to communicate with the public, and that’s surely true. But we tend to forget that filmmakers were sometimes talking to each other. In the Zanuck-produced Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), a romance of silent-era moviemaking, director Don Ameche turns down Rin-Tin-Tin for a project. The obvious joke is that the pooch became a big star, but how many viewers would appreciate the in-joke that Zanuck launched his career at Warners writing scripts for Rinty? Did the public know that Slim and Steve, the nicknames swapped between Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not, were the ones used by Hawks and his wife? Would ordinary moviegoers catch the reference to Archie Leach in His Girl Friday or notice Jed Leland’s column in the newspaper in The Magnificent Ambersons?

Some would have. Moviegoers of the day were better-educated than the populace in general, and the biggest fans went several times every week. But even if the audience missed these bits, the filmmakers’ peers might not. These movies were made by youngish people who liked to have fun–sometimes at each other’s expense—and nothing is more fun than very esoteric in-jokes.

The problem is that these other examples are highlighted in dialogue, but some of Miracle‘s in-jokes are almost completely buried. They’re more akin to the current vogue for Easter Eggs in sets and props. Unlike the recent instances, though, Sturges’s hints are hard to catch during projection, and he couldn’t have counted on viewers mulling over them frame by frame, as our directors can.

Perhaps he intended to show those posters more fully but had to forego that option during filming or cutting. Or perhaps he included them just for his own amusement–that is, not for the general public, nor even for his peers, but merely for the pleasure of putting in things that only he and his team knew about. If that seems implausible, let me ask: If you could do it, wouldn’t you?

The fourth poster, after some fiddling with the Skew and Perspective tools in PhotoShop, reveals itself as another aerial adventure: Eagle something…. Eagle Blood, maybe? For an example of a drama using real film titles in its movie marquees, see this entry.

On duals and triples, see “Triple Features Seen as Nabes’ Salvation,” Variety (22 January 1935), 3; Dan Goldberg, “Chicago Merry-Go-Round,” Variety 24 October 1938, p. 21; “Now It’s Duals, with Vaudeville, At the Loop Oriental,” Variety (25 January 1939), 5; “Single-Billing Idea Up Again But Practically It’s Still NSG,” Variety (26 August 1942), 13. On the St. Louis controversy, see “Better Film Council Queries St. L. Exhibs on Duals and Triples” Variety (23 October 1940), 21, and “St. Louis Group Seeks to Outlaw Triple Features,” Variety (26 February 1941), 21.

The embedded ad for a triple feature comes from The Racine Journal-Times (11 July 1942), 8.

No need to write me about the most obvious in-joke in Morgan’s Creek: the fact that it incorporates two major characters from The Great McGinty (1940) and doesn’t even bother to credit the actors. Cheeky, this Sturges fellow.

From The Daily Gazette (Berkeley , California, 19 October 1942).