You and me and every frog we know

Sunday | September 20, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

Frog TV (2014, N. Joe Myers).

DB here:

Be patient, the frogs are coming. But first, a bit of film theory.

Movies in code

Once many film scholars were captivated by the idea that our responses to a movie were coded, we might say, all the way down.

Here, code means something like a way of assigning meaning that is both arbitrary and relative to time and place. The code is arbitrary in that it might just as easily have been otherwise. A code is relative because in different circumstances it might vary.

One prototype for the early semiologists was the code regulating traffic. In a traffic light, there is no natural or necessary connection between green and “Go!” or red and “Stop!” We’ve just agreed on these meanings. We could have assigned red to “Go!” and green to “Stop!” And indeed other cultures might do just that. A gesture may mean something friendly in one culture and something naughty in another.

The presumption is that because a code is both arbitrary and relative, it has to be learned. You need to live in a culture to understand the traffic code and the code of gestures. Through either observation or training (such as learning the codes of written language) you master the codes of your culture.

Clearly, movies include many codes. A film can show us traffic lights or hand gestures. Films include language as well, which is coded to a high degree. The crucial question is: How much in our responses to film is coded?

Almost everything, some said. There was a wing of semiology ca. 1970 that suggested that both what’s represented in film and the ways things are represented are arbitrary and culturally variable in the extreme. Some theorists suggested that just recognizing an object in a shot relies not on natural perception but rather on a code. Indeed, the argument was made that “natural” perception is itself coded. A favorite corollary of this was that language was such a powerful code that it reshaped perception. Put bluntly, if your culture’s language doesn’t distinguish red from green, you won’t see the traffic light’s top and bottom lamps as different colors.

I resemble that remark; or do I?

Surely, somebody will say, many film images resemble the things they portray. A shot of a man and a woman looks, in certain relevant respects, like a man and a woman. We’re able to recognize them as such. Yet 70s semiology held that there was nothing natural about this. The image-object resemblance, often called “analogy,” and “iconicity,” was considered to be coded.

Here, for instance, is Umberto Eco in 1967:

We know that it is necessary to be trained to recognize the photographic image. . . . Even if there is a causal link with the real phenomena, the graphic images formed can be considered as wholly arbitrary.

Christian Metz brings out the cultural variability of recognition in a 1970 essay:

The apprehension of a resemblance implies an entire construction whose modalities vary notably down through history, or from one society to another. In this sense the analogy is, itself, codified.

Here is Dudley Andrew commenting on this line of thought in 1984:

The discovery that resemblance is coded and therefore learned was a tremendous and hard-won victory for semiotics over those upholding a notion of naive perception in cinema.

The semiological tradition pointed out, correctly I believe, that the parallel between the image and the thing it represents lies not in some relation between the two but in the comparable ways in which we understand each one. But can this process be considered both arbitrary and relative?

Can we, for instance, imagine a culture in which recognition was fundamentally arbitrary—where a picture of a bunch of bananas depicts, by cultural fiat, a clutch of cherries? More exactly, where a picture of a bunch of bananas is seen as a clutch of cherries?

We can imagine a very capricious filmmaker who set up a code with an introductory credit:

Every time I show you a shot of bananas, see cherries.

But you couldn’t see cherries. At best, the result would involve imagination, not perception. Even cooperative spectators would recognize the bananas as bananas, though they would go on to think of cherries.

The distinction between perception and thought seems to have been blurred in semiological theory. Perhaps the 70s arguments traded on the various meanings of “perception”, such as “I perceive that he’s unhappy today” or “I want to change your perception of Rosicrucianism.” The same would go for various senses of “recognition”: “I recognize the father’s face in the son,” “He had aged so much I didn’t recognize him.” These senses of the word bring in matters of conception and attitude, not just visual input.

Perception and evolution

Not that perception is easy to define. When the semiologists were writing, they may have been influenced by psychological theories that assigned a big role to concepts in perception—“top-down” models that claimed perception to be “cognitively penetrable.” It’s fair to say that there’s now good evidence that the perceptual activities involved in visual recognition are largely fast, automatic, fairly dumb, and cognitively impenetrable.

Another error, it seems to me, was also the product of the period: the ignoral of evolution. The 1970s advocates of sociobiology seem to have been simply ignored, perhaps because they seemed to be naïvely attempting to see culture as nature. Yet I think that J. J. Gibson was right (also in the 1970s) in proposing that evolutionary theories could help explain why perceptual recognition is so swift and efficient.

Creatures evolved in an environment that selected for accurate perception, including very very very fast recognition of predators, prey, and mates. Evolution, we might say, provided long-term survival training in recognition, weeding out any creatures who didn’t register salient features of their world. A hominid who needed explicit teaching to recognize a tiger wouldn’t last as long as one who came to the task with senses pre-tuned. As with learning spoken language, all that would be needed is some exposure to the regularities of the ancestral environment. The baby born into our world is bombarded with redundant information that is non-arbitrary and non-relative; she quickly grasps that a face is more informative than a knee. It will take her quite a bit more time, along with some tutelage, to learn traffic signals and even more to learn to read.

Cinema taps some of our most fundamental capacities. Film images aren’t reality, but they present certain salient triggers for us to recognize what they represent. Indeed, the very perception of motion in movies is an illusion—a glitch in our visual system that cannot be arbitrary or culturally relative. Nobody in any time or place sees movies for what they are, a succession of still images. There are enough cues for movement to fool everybody’s visual system. And films preserve enough other features of the world to trigger automatic recognition processes. Perceptual recognition of something in the image is on the whole neither arbitrary nor culturally variable.

The likeliest conclusion is that we share with other creatures some native propensities which, given the right early exposure to the physical and social world, will be exercised in comparable ways. Of course there are differences. Minnows can’t enjoy Matisse, and we can’t smell as well as dogs can. Still, sensory systems overlap among many species.

So consider the frogs of the field: they toil not, neither do they spin.

Frogs like the front row too

We know quite a bit about how frogs see the world. A classic paper in animal neurology, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” was crucial in suggesting the highly specialized nature of nerve fibers feeding information to the visual system. Those data streams—about edges, movement, and variable illumination—get reintegrated, but not necessarily thanks to high-level mental activity. “Early vision,” in frogs and in us, involves not some some brainy entity interpreting the image on the retina but rather several specialized, quite stupid systems that pool information before thought ever enters the picture. No codes necessary. What came to be called “distributed processing” does a large share of the job.

Though untrained in the codes of our culture, these frogs appear to recognize what matters to them, even on the mini-movie screen. (Sorry the video embed no longer works.)

If pigeons can quickly learn to interpret human faces in pictures, and female jumping spiders react to video images of males as if they were real, we shouldn’t be surprised that frogs can respond very—ah—actively on first exposure to movies showing things they really care about.

Of course a lot of our activity isn’t as data-driven and mandatory as recognition. Higher-level concepts do all sorts of work when we watch movies, from understanding who the protagonist is to grasping a film’s theme or point. And of course all manner of conventions in films require sophisticated cultural knowledge. My point is just that some aspects of our response are very basic. I hazard that our responses to cinema mix together all kinds of skills, abilities, biases, and proclivities. A movie is a package of appeals, a buffet with something for all our visual and auditory appetites.

First, thanks must go to N. Joe Myers, who posted this neat experiment in natural perception a year ago. (Has the filmmaker tried it with an iPad or a computer monitor that would make the worms look huge? Would that induce large-scale frog panic?) For vastly more frog-related information, go to N. Joe’s page here.

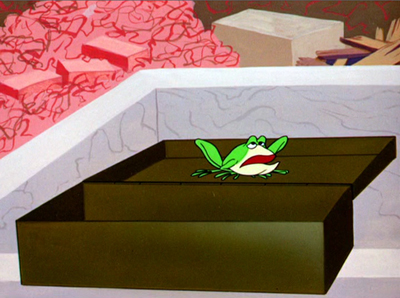

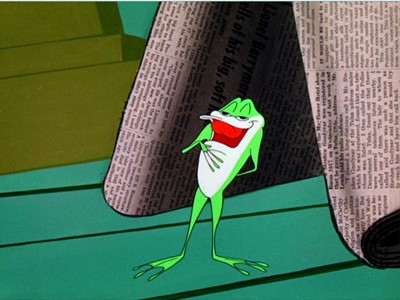

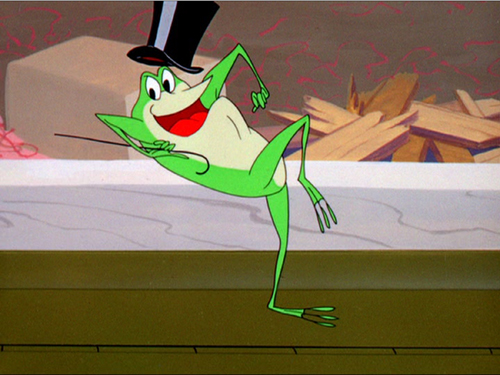

Thanks also to Darlene Bordwell, who called the piece to my attention, and Barb Anderson who pointed me to the spider studies. The illustrations are of course from Chuck Jones’ Warner Bros. cartoon One Froggy Evening (1955).

My quotations are from Umberto Eco, “Articulations of the Cinematic Code,” and Christian Metz, “On the Notion of Cinematographic Language,” both in in Movies and Methods, ed. Bill Nichols (University of California Press, 1976), 594 and 584; and Dudley Andrew, Concepts in Film Theory (Oxford University Press, 1984), 25. See also Metz, “Au-delà de l’analogie, l’image (1969),” Essais sur la signification au cinéma, vol. II (Klincksieck, 1972): “Resemblance itself is codified, because it makes appeal to a judgment of resemblance: the judgment of an image’s degree of resemblance will vary according to the time and place” (154).

J. J. Gibson’s writings mounted a strong case for what he called “direct perception” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Houghton Mifflin, 1979). His ideas were developed by Claire F. Michaels and Claudia Carello in Direct Perception (Prentice-Hall, 1981) and, more critically, by James Cutting in Perception with an Eye for Motion (MIT Press, 1986); pdf. Joseph Anderson’s The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (University of Southern Illinois Press, 1998) is the trailblazing application of Gibson’s ideas to cinema. More generally, Paul Messaris’ Visual Literacy: Image, Mind and Reality (Westview, 1994) reviews the empirical findings that show virtually no cultural variability in perceiving line drawings and photographic images as depictions of recognizable persons, places, and things.

At some point in discussions of the cultural variability of perception, someone is likely to mention Eskimo cultures’ purported range of words for snow. But this is a long-standing error. See Geoffrey K. Pullum’s The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language (University of Chicago Press, 1991) and John H. McWhorter’s The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language (Oxford, 2014).

What happened to these 1970s beliefs about the film image’s coded nature? It seems to me that when semiology as a research perspective waned, academics mostly stopped talking about the issue of resemblance and recognition. Researchers retained a general sense that films are coded, but they concentrated on less controversial conventions, like social stereotyping, representations of power, and so on. I’ve been told that the level of perception is merely a matter of “physiology” (wrong word) and thus of no consequence for the important issues that scholars should be studying. But of course filmmakers shape our response chiefly by controlling our perception, and if we want a comprehensive account of how films work and work on us, we can’t ignore this level of the viewer’s activity. I consider this problem in the title essay of Poetics of Cinema.

For a more developed argument about how films bundle a range of appeals, from sensory triggors to high-level concepts, see my essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. Online, I discuss these matters here and here and here (under “Representational Relativism,” which involves not frogs but our ancient ancestors).

P.S. 21 September 2015: Apes appear to remember episodes after watching movies. Thanks to Bill Evans.

One Froggy Evening.