Still Agnès

Monday | November 23, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

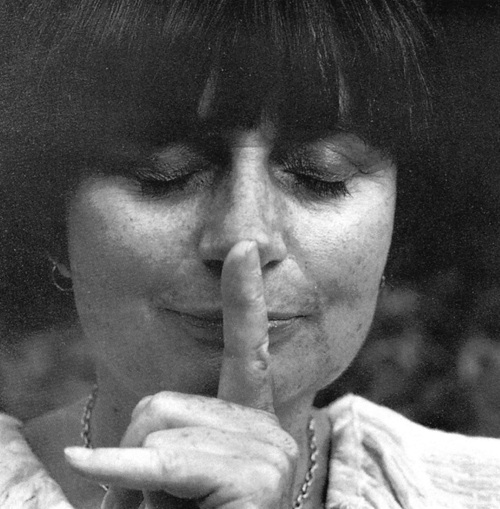

Self-portrait by Agnès Varda.

DB here:

Sixty years ago, a twentysomething photographer released a film shot in an out-of-the-way French fishing village. Coming right after Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy and Fellini’s La Strada (both 1954), the result announced something new in cinema. Like those other works, it looked forward to the French Nouvelle Vague and the cinematic modernism of Antonioni, Bergman, and a host of other filmmakers.

But the status of Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1955) became apparent only with the most distant hindsight. It didn’t win big attention on the festival circuit, in the international market, or in the pages of highbrow film magazines. Denied a commercial release, La Pointe Courte circulated mostly in French ciné-clubs. In the early 1980s, when I saw it at the Brussels Cinematek, it was still a rarity.

Thirty years after La Pointe Courte, Varda’s career reached a new level. Vagabond (Sans toi ni loi, 1985), widely recognized as her masterpiece, remains one of the great achievements of that modern cinema she helped create. And she hasn’t exactly been idle since. There have been many films both long and short, including a biopic of her husband Jacques Demy in Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and the picaresque The Gleaners and I (2000); the fascinating autobiography Varda par Agnès (1994); and over the last decade a series of installations in museums around the world. She started as a photographer, became a cinéaste, and is now a plasticienne, a maker of painting and sculpture.

She is eighty-seven years old.

Agnès V., not B.

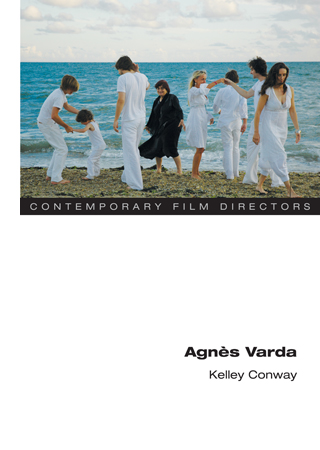

Our colleague Kelley Conway has just published an authoritative consideration of the work of this shrewd, unpredictable survivor. Reading Kelley’s book reminded me of that encounter with La Pointe Courte.

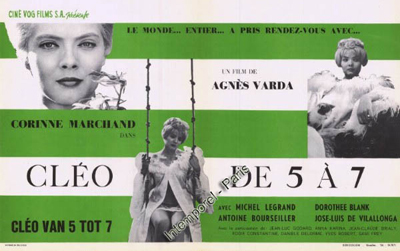

I had known Varda’s more famous works: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961), screened at my college film society as the project of a New-Wave fellow-traveler; Le Bonheur (1965), which might be called Jules et Jim revisé et corrigé; One Sings the Other Doesn’t (1977), which got circulation among other feminist films of the period. These didn’t prepare me for La Pointe Courte’s daring mix of realism and minimalism. Varda wanted, she said, to make a film that was the equivalent of a difficult book, and for me she succeeded.

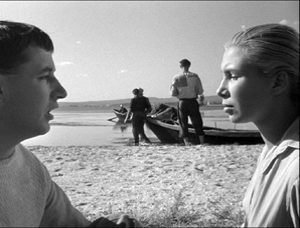

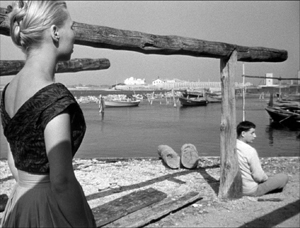

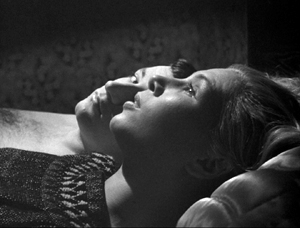

The film alternates sunny images of local life—fishing, net-mending, washing-up, a festival—with episodes in which a Parisian couple drift through the village, oddly detached from the life around them. The everyday scenes are shot in documentary style, but with a casual rigor suggesting Cartier-Bresson. Meanwhile, the couple talk in stylized compositions that could only remind me of L’Avventura.

No wonder Picasso was Varda’s favorite painter: she splits up the couple’s faces with cubistic zeal.

The disjunction between the actuality of a location and the abstraction of the couple’s anomie-riddled duet, often heard only as voice-over commentary, looks forward to Hiroshima mon amour. (No wonder: Resnais edited the film.) I barely understood the French, but the film gripped me. It was of great historical interest, and it had its own stubborn vivacity. When Kristin and I planned the first edition of Film History: An Introduction (1994) I made sure it got in. In that year, forty years after it was made, La Pointe Courte was released on VHS.

Things change. Varda is now regarded as a living treasure of world cinema, preserved in excellent Criterion DVD editions, available for streaming on Hulu, and wrapped up in a vast cube, Tout(e) Varda (20 features, 16 shorts). Whatever she does in the future, we can at least take a long-distance measure of her accomplishments.

The dream of many writers on a single director is to cover it all: appreciative study of the films, background on how the films came to be, assessment of their immediate impact and long-range influence. But this breadth of understanding is very hard to achieve. Where are the documents? How do you get the filmmaker to talk?

Kelley has done it. Her book combines film analysis, historical research, and information drawn from Varda’s archives. Kelley can tell us how the films came to be, what Varda wanted to accomplish, and how they were received. To top it off, there’s a new interview with Agnès herself.

Crossing landscapes

Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993): Varda and Deneuve.

With a brisk practicality echoing that of her subject, Kelley has focused her lens tightly. You can’t quarrel with her choices: La Pointe Courte, the early short documentaries, Cléo, Vagabond, The Gleaners, two installations, and The Beaches of Agnès (2008). Her plan of attack is straightforward: scrutinize the film, then work backward to the conditions of production and forward to the film’s reception.The analyses are models of attention to story and style, images and sounds. Kelley pins down what intrigued me about the acting in La Pointe Courte, showing its debt to Brechtian distancing (a big influence on Varda). She goes on to connect the performances to the experiments in “flat” performance we find in Tati and Bresson at the same period. Kelley shows how many of Varda’s artistic strategies, such as whimsical puns and a love of digression, go back to her early documentaries.

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

Another legacy of documentary: Kelley points up how even the fiction films spring from an attention to the specifics of a locale. “Part of Varda’s journey is regularly exploring a chosen region at length, waiting for ideas, emotions, and images to emerge.” That region might be a single Parisian street (L’Opéra-Mouffe, 1958; Daguerréotypes, 1975) or the fourteenth arrondissement (Cleo from 5 to 7). Like La Pointe Courte, Cleo is the story of a walk, this time purportedly played out in actual duration as a beautiful pop singer awaits the results of a test for cancer. Mona, in Vagabond, is another wanderer, and the wintry bleakness of southern France is as central to the action as whatever psychology we can find in her or the people she meets. The Gleaners and I searches out people who stalk the landscape and live off what they can scavenge. With modern cinema from Bicycle Thieves onward, Dwight Macdonald once noted, “The talkies have become the walkies,” but Varda has always embedded her footloose protagonists in the particulars of place.

Varda’s personal archive has given Kelley the opportunity to document the director’s creative process. The scripts are sometimes scrapbooks, with texts and images jostling one another. (Kelley offers an example in a 2011 blog entry.) The arrival of digital tools reinforced and expanded Varda’s method of free assembly. Out of a database of images, Varda erected the scaffolding of The Beaches of Agnès before starting her screenplay. She wrote, shot, and edited the whole thing in a nonlinear fashion. During the final stages, two editors worked busily in separate rooms. “I went from one to the other. On one side was Sète and Los Angeles, in the other room was Belgium and Paris.”

As for exhibition, crucial to Varda’s early films was a distinctive French institution. Varda had created her company to make shorts, but when La Pointe Courte grew to 80 minutes, it could not be distributed under those auspices without new investment. As a result, it found its main audience in the network of ciné-clubs that had grown up after World War II. That network became activated to the maximum during the release of Cleo from 5 to 7. One of the side benefits of Kelley’s book is its explanation of the power that the ciné-club scene had achieved by the early 1960s.

Brandishing the slogan “Develop Film Taste, Introduce Masterpieces, Educate the Public,” an astonishing five hundred clubs with over two hundred thousand members showed thousands of films in the year that Cleo was released. Varda took advantage of this situation to promote her film, but Kelley goes beyond the simple marketing issue to point out that the clubs bolstered spectators’ appreciation of New Wave films. She draws on audience comments to show that the organizers guided audiences to talk about form, style, theme, and historical context. The clubs helped create the “demanding viewer” described by Alain Resnais: a viewer eager for challenging films that could bear comparison to advanced works in traditional arts.

Varda’s later films were absorbed into the mainstream commercial distribution/exhibition infrastructure, and Kelley is painstaking in plotting critical response to them. Near the book’s close, she traces how another institution shaped Varda’s work: the museum. Kelley shows how the emerging importance of installation art encouraged filmmakers like Varda and Chris Marker to create multimedia exhibits that were natural continuations of their poetic-essayistic documentaries. The installations seem to have encouraged Varda to take up the autobiographical compilation mode that yielded The Beaches of Agnès.

There is much more in Agnès Varda than I can summarize, but I hope I’ve piqued your interest. For any lover of Varda, Kelley’s book is a must, and even casual viewers will learn things that will drive them to the films. Reading it led me to think about how Varda’s lack of cinephile culture (she emphasizes that she knew nothing of film when she started) allowed her to respond to stories more directly than did the Bad Boys of the Cahiers, who saw everything through a mesh of hundreds of other movies. I was also prodded to think of her as quite an innovator in narrative. She has given us the parallel structure of La Pointe Courte, the fantastic science-fiction plot of Les Créatures, the isoceles love triangle of Le Bonheur, the dual-protagonist structure of One Sings, and the network narrative of Vagabond, with Mona as a circulating object a bit like Bresson’s Balthazar.

From the delightful interview with Lady Potato herself, I allow myself just one spoiler:

KC: You seem to start your projects with considerable preparation but you also have a flair for improvisation. Do you see it that way also?

AV: Yes and no. Or no and yes, depending.

An earlier entry discusses a Kelley talk on La Point Courte. I discuss some ambiguous narrative cues in Vagabond in my updated “Art Cinema” essay in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

This has been a good publishing year for our colleagues at Wisconsin–Madison. Lea Jacobs’ book on filmic rhythm came out last winter; go here for our observations.