L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema

Saturday | April 9, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

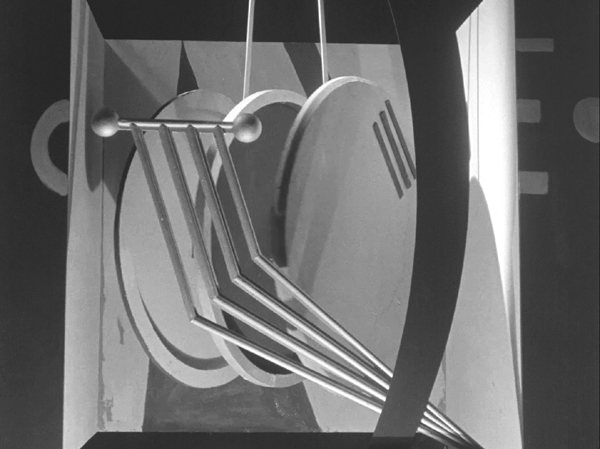

Flicker Alley continues its relationship with Lobster Films of Paris, bringing out beautifully restored versions of French silent films, and in particular the work of the French Impressionist filmmakers. The recent release of Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924) is stunning visually. L’Herbier produced the film himself with his new Cinégraphic company, and hence he preserved the negative. With the original art-deco intertitles (below) and the colors as chosen by L’Herbier, this is as close as one can get to a version that is identical to the original release prints.

We’ve described earlier Flicker Alley releases of classic French silents in restorations: the extraordinary output of the Russian emigré firm Albatros, the long-lost serial La Maison de mystère, and Abel Gance’s La roue. L’Herbier’s Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), made directly after L’Inhumaine, was in the Albatros set but also released separately.

Although I’ll be mentioning most of the major plot points of L’Inhumaine, I’m not posting a spoiler alert. The action does involve some nominally suspenseful situations, but L’Herbier signals what’s going to happen so far in advance that I suspect few people watching the film would be surprised by the “twists” in the story.

The film’s plot is, to put it bluntly, weak. The “inhuman one” of the title is Claire Lescot, an opera singer who delights in frustrating the powerful suitors and would-be seducers who gather at banquets that she stages in the spectacularly designed rooms of her lavish home. In the opening dinner scene, she is particularly cool to Einar Norsen, a brilliant but naive young inventor who is in love with her. When he seemingly threatens suicide, she laughingly remarks that his life cannot mean much if he can throw it away.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

The mysterious man, as is obvious from the start, is Norsen in disguise, preparing an ordeal that will lead Lescot to renounce her cruelty and embrace humanity. (The plot of a man who takes the opportunity afforded by a false report of his death to adopt a new identity apparently fascinated L’Herbier. It would become the core of Feu Mathias Pascal, an adaptation of Luigi Pirandello’s 1904 novel.)

Once Norsen reveals himself to Lescot, he shows her his remarkable laboratory, including a machine that may be able to restore the dead to life.

Lescot’s interest in Norsen has enraged one of her suitors, Djohar de Nopur, and he kills her using a poisonous snake in a bouquet. Norsent rushes her to his laboratory and uses his new invention to revive her.

We learn very little about these characters. They are basically stock figures enacting a familiar melodrama. Georgette Leblance, who plays Lescot, was an opera singer who contributed half of the financing in exchange for playing the role. She employs the florid style associated with the great divas of the 1910s, emoting intensely and striking dramatic poses.

If one embarks upon watching L’Inhumaine as a compelling story, one is likely to be disappointed. Its fascination lies rather in the fact that this simple narrative is considerably embellished with flashy design and the novel depiction of scientific experiment.

A leisurely stroll through some remarkable sets

“Flashy design” here means a great deal. L’Herbier had many prominent friends and contacts within the world of arts and crafts in 1920s Paris. The assemblage of collaborators who worked on the look of L’Inhumaine is quite overwhelming. The heroine’s clothes were by one of the leading fashion designers of the day, Paul Poiret, whose interior design department contributed some of the furniture in her apartment (below). The sculptures in her home are by Joseph Csaky, a Hungarian-born Cubist.

There were four main set designers, with contributions by others. Modernist architect Robert Mallet Stevens created the exteriors of Lescot’s house (left) and Norsen’s (right).

By the way, one can still almost walk into a 1920s film today by visiting the Rue Mallet Stevens in Paris, here seen at the time of its inauguration in 1927.

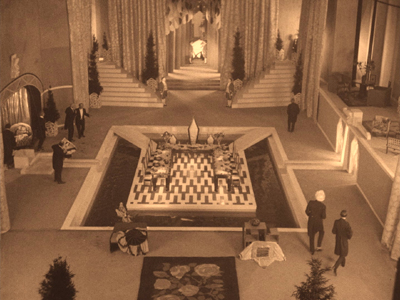

Other designers included Alberto Cavalcanti, who designed the interiors of Lescot’s mansion, notably the huge dining and entertainment hall at the top of this section and a Caligaresque conservatory.

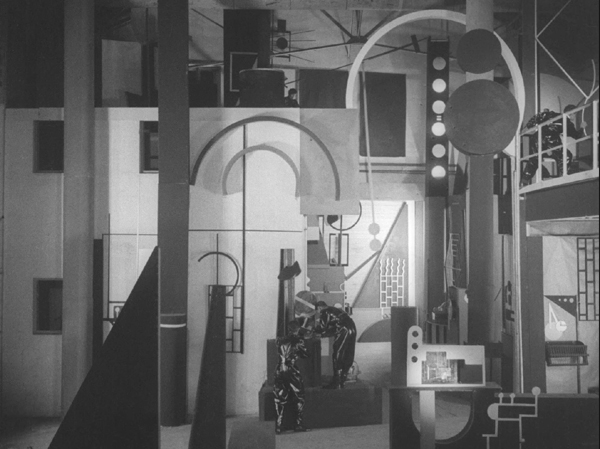

Perhaps most memorably, painter Fernand Léger planned and built the interior of Norsen’s lab (see bottom). More on this below.

The bare bones of the plot are so simple that L’Herbier can proceed at a remarkably leisurely pace through individual decors. In a period when most films consisted of long strings of short scenes, Claire’s opening banquet for her gentlemen guests lasts a remarkable 45 minutes. This includes cutaways to Einar driving rapidly to her house, dithering about whether he should appear late at the party, and finally, after her callous treatment of him, driving away to his apparent suicide. The second sequence, with Claire deciding to perform her song recital despite her grief over Einar’s death, lasts 25 minutes. The primary action here is simply a near-riot in the theatre between her supporters and those indignant about her part in the causing the young scientist’s death.

The lengthy final section of the film visits the laboratory three times, allowing us to get a good look at one of the great sets of the era.

Cinematic touches

L’Herbier did not entirely depend on his designers to carry the visual interest of the film. He was precocious in his use of wide-angle lenses, a technique that would become more prominent in his 1928 masterpiece, L’Argent. Here the lenses used give a less obvious effect, as in the shots of the jazz band that entertains during the opening banquet (above).

He also achieves some impressive compositions using considerable depth of field, most notably a close-up of the hero’s steering wheel as he tears along a road overlooking a deep valley with a city in the distance. It is here where his supposedly suicide takes place. Another striking shot has the jealous villain in the dark foreground, watching as the disguised Norsen enters Lescot’s dressing room.

Très moderne

Although the combined work of such a group of designers is the film’s primary attraction, L’Inhumaine is also notable as an early example of the science-fiction genre. Norsen’s technical genius is represented as going beyond the technology of the age. We see two instances of what he has invented.

The first marvel of Norsen’s laboratory that he demonstrates to Lescot is a television set (so named in the intertitle). Is this the first reference to television in the cinema? Possibly, though the script in quite an illogical way reverses the technology of how actual television would eventually function. Lescot performs a song into a microphone. Instead of a camera beaming her image out to viewers around the world, a screen in Norsen’s lab shows her images of various listeners reacting in delight to her performance–as if somehow cameras could be placed in every spot where someone, whether Arabs, a young black woman in an African field, or a family group in a tropical setting (below) is listening to her over a radio speaker.

The telephone system in Metropolis (1927) that includes screens upon which the speakers view each other reflects more reasonably what actual inventions were later to follow. One can’t help wonder, however, whether that device was inspired by L’Herbier’s film.

More spectacularly, the giant machines that Norsen uses to restore Lescot to life provide the climax of the film. When Norsen tours Lescot around his lab in an earlier scene, he shows her a huge apparatus, including three large, round components that swing through space like a moving Gabo sculpture (see top). He remarks that he believes the machine could restore a dead person to life, but he has not yet had the opportunity to test it.

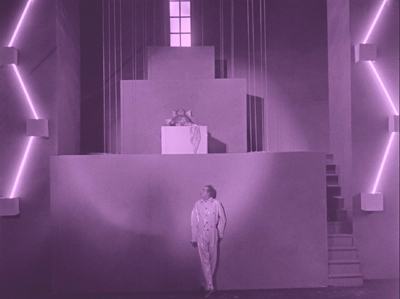

Rather than trying to suggest how the machine works, the film keeps the set where Lescot lies dead simple and abstract. In perhaps the most famous image from the film, a ziggurat-shaped platform and some simple diagonal lighting tubes shape the composition, with Norsen nervously peering up to gauge the effectiveness of his invention (see top of this section).

The scene of Lescot’s revival consists of rapid, accelerated editing that had become a major trait of the French Impressionist movement by this time in the wake of La roue and Jean Epstein’s Cœur fidèle. There is no way to convey this remarkable sequence with frames from individual shots; the effect is achieved more by the rhythm of the cutting than by the composition of the individual shots.

The Flicker Alley Blu-ray comes with two alternative musical accompaniments, one by the Alloy Orchestra and an adaptation of the original Darius Milhaud score by Aidje Tafial. We listened to the latter, which worked very well with the film. There is also a helpful booklet of notes.