Refutations of the death of cinema, courtesy the VIFF

Wednesday | October 12, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

Maliglutit (Searchers)

Kristin here:

About three weeks ago David pointed out that the “death of cinema” being bewailed by many critics and pundits was based largely on the disappointments of the summer of Hollywood blockbusters. Taking a larger perspective, the cinema looks to be thriving. Herewith some further evidence as we continue to enjoy the rich schedule of screenings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some of these films are good, some very good, some perhaps great and destined to be watched for decades to come.

Maliglutit (Searchers)

In 2001 the first Inuit-made feature film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner won the Golden Camera at Cannes. Admirers of it, among whom we count ourselves, have wondered whether there would ever be a follow-up. Since Antanarjuat, director Zacharias Kunuk has had an active career in documentaries. Now, however, he has returned with a second fiction feature, Maliglutit (Searchers).

The title proclaims the film’s inspiration: John Ford’s The Searchers. Kunuk wanted to make a western, but one “made entirely the Inuit way.”

From the start, I resolved to anchor the production in my home community of Igloolik. It was important to get the faces right. I brought on Natar Ungalaaq, who played the lead in “Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner,” as co‐director to work with the actors preparing their performances and to mentor a new generation of Inuit filmmakers. Our cast and crew included regular collaborators, but also a number of new people in training.

Igloolik is a small island in the Northwestern Passages, far to the north in Canada. It’s population is about 2000. An extraordinary place for such important films to come from.

Maliglutit can hardly be said to be a remake of Ford’s film. Its borrowing from The Searchers is solely the kidnap plot. The hero is Kuanana, whose wife and daughter are carried off on dogsleds by four members of a neighboring tribe, led by Kupak. Kuanana and his son give chase. Unlike in The Searchers, there is no conflict between the older and younger men. Unlike Ethan Edwards, who is revealed to be hunting down the tribe who kidnapped Debbie in order to perform a sort of honor-killing, Kuanana simply wants the women back. The psychological complexities of The Searchers are replaced by a focus on the details of Inuit life in 1913 (an era in which firearms were starting to replace traditional weapons, above) and the frightening beauty of the bleak late-winter landscapes through which the chase progresses. The two women resist and seek to escape during the entire chase, and they play an active role in the climactic rescue.

Although virtually all of the crew were also local Inuits, producer and cinematographer Jonathan Frantz, was a crucial figure. He created epic images of the harsh, snowy landscapes during the chase (see top), often shot in the early morning light of March.

Maliglutit seems to have no distributor. Watch for it in other festivals and eventually on home video–though the scale of the compositions really demands a big, big screen.

From a textbook to an upheaval

If women directors are still struggling to establish themselves in Hollywood, they are much in evidence here at Vancouver. Films from a wide variety of countries were helmed by women, including Mia Hansen-Løve (or Mia Hansen Love as she is billed here), who won the Silver Bear award for best director at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Bucharest International Film Festival. (See here for an interview with the director shortly after the Berlin premiere.)

Her Things to Come (L’avenir) well demonstrates her mastery of traditional, skillful filmmaking. Her camera is locked down rather than restlessly roaming, with simple reframes to follow actors’ movements. The compositions are impeccable, the editing clearly planned in advance, and the story told in an unobtrusive, clear fashion.

I found the film appealing partly because it presents that rare thing, a plausible depiction of the life of an academic. The heroine, Nathalie, played in another star turn by Isabelle Huppert, teaches philosophy in a Parisian high school. Her students are obviously sophisticated kids, and she finds fulfillment in her work. Her husband is an intellectual, and they have two children. Her life seems ideal and her future certain. In the course of the film, however, she suffers a series of setbacks.

Amusingly, these are initially signaled by a meeting with editors at the publishing house that has brought out her textbook and will be publishing a collection of essays aimed at classroom use. The editors cheerfully show her some garish designs intended to boost sales. Her husband announces that he’s leaving her for another woman, her mother needs to be institutionalized, and she loses her job.

The future is suddenly turned upside down, and the film depicts Nathalie’s efforts to maintain her usual cool, in-control demeanor while seeking a new path in life. Although the film is quite sympathetic to her, there is considerable humor as well. Entertaining, thought-provoking, and visually lovely.

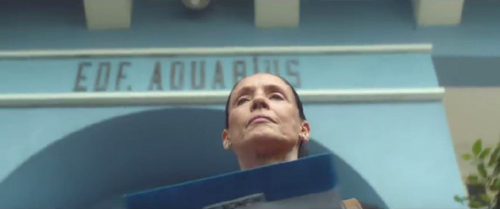

The aging of Aquarius

I was very impressed by Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds, shown at the 2012 VIFF. I have been hoping to see another of his films, and this year the festival presented Aquarius. I can’t say that it was quite as exciting as the earlier film, but it is an admirable and entertaining achievement nonetheless.

Again Filho sets his story in his native city of Recife and again the story revolves around predatory real-estate developers building high-rise residences by buying up and bulldozing beautiful old neighborhoods. The earlier film wove together stories of several families living in such a neighborhood, threatened both by criminals and by the encroachment of modern, soulless towers. Aquarius focuses instead on one wealthy dweller in an otherwise empty apartment building, Aquarius.

The one holdout is Clara, a beautiful, wealthy retired music critic in her 60s, who endures various attempts to drive her to sell her apartment. The unscrupulous developers stage a “party” in the empty apartment above her–an orgy and apparent porn shoot. They burn the resulting filthy mattresses in the communal courtyard. They try to catch her in a legal technicality when she has the façade of the building painted, and things only escalate from there.

The film’s effectiveness depends to a considerable extent upon the riveting central performance by Sonia Braga, best known to English-speaking audiences from her lead role in Dona Flore and Her Two Husbands and Kiss of the Spider Woman. A cancer survivor (as demonstrated by Braga when she bares an apparently real mastectomy scar), Clara commands complete sympathy as she fearlessly stands up to her devious persecutors. Despite her wealth, she is friends with her housekeeper and well aware that a short way down the beach across from her apartment, there is a poor neighborhood even more threatened by the developers than hers is.

As in Neighboring Sounds, Filho includes shots of the nearby high-rise blocks looming over the beautiful older buildings. In my earlier entry, linked above, I quoted an interview where the director said, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.” Here the “wrong” architecture is bland, and the older buildings are photogenic.

Aquarius will begin a New York theatrical run on October 21. (Thanks to Erik Luers for the link!)

A poet for, if not of, the people

Another Latin American film shown at the 2012 VIFF that I wrote about favorably was Pablo Larrain’s No. Now he follows up with Neruda. Here we have another film about a poet, in this case the Nobel-prize-winning Chilean author Pablo Neruda. The film follows the dramatic events in 1948 when Neruda’s Communist activities led to a warrant being issued for his arrest. After living in hiding for some months he fled through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake (above) into Argentina and from there to France.

Not surprisingly, many scenes center around Neruda, played powerfully by Luis Gnecco, an actor more typically associated with comedies. (He played the Ricky Gervais/Steve Carrell role in the Chilean version of The Office.) Equally prominent, however, is the police detective who relentlessly pursues Neruda, Óscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal).

Peluchonneau is at once a real detective, a figure fascinated by his quarry, and perhaps a figment of Neruda’s imagination. In a crucial scene, Peluchonnaeau interrogates Neruda’s endless patient and faithful wife (marvelously portrayed by Mercedes Morán; see bottom), and she informs him that he is a mere supporting character invented by her husband. This seems improbable, since Peluchonneau has important causal effects in the narrative, and indeed, his narrating voice continues throughout the film, filtering much of the story information to us. Still, he plays out his supporting role until the end.

I was startled to discover that he and Neruda are parallel protagonists. My Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) took Amadeus, Desperately Seeking Susan, and The Hunt for Red October as examples of this fairly rare category. Parallel protagonists largely play out their roles independently, but they are aware of each other and fascinated with each other. One may feel inferior and yearn to be like the other. In Neruda, Peluchonneau is clearly fascinated by Neruda and wishes to be like him. He is, however, far less clever and talented. (Jay Weissberg’s Variety review compares him to Inspector Clouseau.) The ending leaves his status as a character quite ambiguous. It’s nice to know that this unusual option is used in art cinema as well as Hollywood films.

There is a distinct touch of magical realism about Neruda, one that fits in well with the art cinema’s departure from mainstream commercial cinema. It does leave you puzzled in a satisfying way.

Quarrels and cabbage rolls

Don’t ask me what the title Sieranevada means. I have no idea what it has to do with anything that happens in Cristi Puiu’s latest feature. If I had to choose a single favorite from the films I’ve seen so far at the festival, it would be a hard choice between Sieranevada and A Quiet Passion. I have to say, though, that Sieranevada is much funnier, though it took me longer than it should have to figure out that it’s a comedy. Watching the lengthy opening shot, which largely involves the main character’s car being double parked and blocking a DHL truck, I did quickly realize that I was seeing a terrific film.

It is something of a network narrative, based on the familiar situation of a family gathering that exposes long-simmering problems and tensions. (Other examples are Altman’s The Wedding and Vinterberg’s The Celebration.) If we had to pick a central character, it would probably be the medical professional Lary, because we enter and leave the central space when he does, we learn the most about him, and we react much as he does to the amusing twists of action. Still, other family members carry a good deal of the film’s running time, and by the end we observe him with a cooler detachment when his own secrets are revealed.

The main locale is the apartment where Lary’s large family is commemorating his father’s recent death. The apartment has several rooms, all of which are fairly small for the number of people milling about. It’s evidently a set, but one which conveys an entirely convincing sense of seeing an actual cramped apartment.

The party is planned to culminate in a substantial dinner. We see the women of the family cooking, setting the long table, inexplicably taking away the unused dishes and utensils, and assembling plates of food wrapped in plastic (above), to be distributed to the neighbors. Few films have made food look so unappetizing. Mainly, though, these people bicker. The party portion of this 173-minute film occupies about 150 minutes, shot in nearly continuous time.

Puiu handles the whole thing in a virtuoso staging of multiple actions going on in different rooms, with the camera often only glimpsing what one group is doing before a door is closed and the camera moves on to catch another group in a another space. Often the camera pans with one character only to change direction as it catches sight of another, as if it continuously seeks out the most interesting bits of action in this densely populated space. Characters air their obsessions: one cousin is a 9/11 conspiracy believer, and an old lady in a white fur hat upsets the others by touting the accomplishments of the Communist past. We hear grievances too, as when the widow’s sister accuses her husband of carrying on an affair with a neighbor.

Scripting the dialogue for this dense weaves of conversations was a considerable accomplishment. Puiu extracts further comedy by putting so much emphasis on the food and then delaying the actual meal for almost the entire duration of the party. First a priest who must perform a memorial ceremony fails to show up, and then a suit which will feature in another ceremony needs emergency alteration when it turns out to be several sizes too large for the hapless young man who must wear it.

In all, despite its three-hour length, Sieranevada is continually entertaining and an extraordinarily assured piece of filmmaking.

U. S. releases: IFC and Sundance Selects have announced Things to Come for 2 December, while Neruda is scheduled to be released for December 16 from The Orchard.

Aquarius was originally expected to be Brazil’s nomination for the best foreign film Oscar, but political controversy has scotched that. There seems to be no prospect of an American theatrical release. Look for it at other festivals and on streaming. So far, Sieranevada seems not to have secured U. S. distribution, but if it does materialize, seek it out in any way you can. It is Romania’s candidate for this year’s foreign-language Academy Award. It would be a well-deserved miracle if it even made it onto the final list of five.

More recent American examples of parallel-protagonist film are Julie & Julia, discussed here, and Public Enemies and Inglourious Basterds, considered here. The first entry also considers an older example, Enchantment (1948).

Neruda (2016).