The eyeline match goes way, way back

Tuesday | March 10, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here—

It’s late January as I write this entry, and in about a month, I’m due in Egypt for my annual three weeks of volunteer work on the Amarna Project at Tell el-Amarna, in Middle Egypt. (For the project’s website, see here, and for my part in it, click on “Recent Projects,” then “Material Culture,” and finally “Statuary.”) So as not to leave David with the entire blogging burden during that period, I’m writing this to be posted during my absence.

Given the occasion, I decided to write about a topic that has popped into my mind now and then: a little connection I observed between techniques of ancient Egyptian art and those of continuity film editing. In their reliefs, Egyptian artists were very conscious of the directions of figures’ gazes, and their strove in most cases to match the orientation of the accompanying hieroglyphs to those directions. This topic is not only appropriate, but it gives me a chance to show off my new hieroglyphic font—and to practice composing texts with it.

The connection between eyelines in reliefs and in film editing first occurred to me several years ago when our colleague Noël Carroll was giving a talk in the film-studies colloquium in the Dept. of Communication Arts here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He dealt with eyeline matches, or glance/object editing and took a cognitive-studies approach.

Noël’s argument was that such editing is not an arbitrary convention and that it draws upon an “innate perceptual behavior” shared by humans to look not just at other people but also at what those people are looking at. (I’m quoting here from the publication of his talk as “Toward a Theory of Point-of-View Editing: Communication, Emotion, and the Movies,” in his 1996 collection, Theorizing the Moving Image, from Cambridge University Press.) This tendency naturally manifests itself when babies begin at two to three months to follow the directions of their parents’ gazes. He claims that eyeline matching “can function communicatively because it is a representational elaboration of a natural information-gathering behavior” and also that such a link to our everyday perception helps make continuity editing easy to grasp.

If we can find comparable sorts of devices in art of a different era and culture, those devices help support claims about “cultural universals.” These are patterns of perception that all cultures share, though they will manifest themselves in art in different ways. Let’s take a look at a sort of eyeline matching that’s used in Egyptian reliefs. Only here it’s not an eyeline and a seen object being matched. It’s a match between an eyeline and the direction its accompanying hieroglyphs face.

Hieroglyphs and their orientation

First, let me get a pet peeve out of the way. A lot of people these days call hieroglyphs “hieroglyphics.” There is no such word, or shouldn’t be. “Hieroglyphic” is an adjective, as in “hieroglyphic text” or “hieroglyphic inscription.” But don’t just take my word for it; look under Etymology in the Wikipedia entry on hieroglyphs. (I note with annoyance that my spell-checker doesn’t highlight “hieroglyphics,” but it does think “eyeline” is wrong.)

Now, about directions. Egyptian hieroglyphs can be written horizontally or vertically, facing left or right. The default orientation is facing right, to be read right to left. How do you know which direction they’re facing? Even if you can’t read hieroglyphs, just look at the signs representing living things. Birds, people, animals, bugs, with rare exceptions they all face the front of the text.

There are all sorts of complicated exceptions to the rightward orientation. The late Henry George Fischer, curator of Egyptology at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote a large book on the subject: The Orientation of Hieroglyphs, Part 1. Reversals (Alas, he never wrote Part 2.)

As Fischer says at the outset, “It is essential to stress the fact that Egyptian art and writing are interrelated to a degree that is unparalleled in any other culture. For it is from this fact that the orientation of hieroglyphic texts derives its logic.” And Egyptian art, despite its strangeness to many eyes, is intensely logical. Each person, creature, and object portrayed in relief will be shown from its most characteristic, recognizable view, whether that be in profile (such as a person’s face, legs, and stomach) or frontal (that person’s eye and shoulders).

In reliefs, the hieroglyphic texts in reliefs function as labels and descriptions of the things depicted or to quote the words of the people present. Hence, logically, the particular inscription relating to one person, creature, or object depicted will face the same direction as it does.

Two straightforward examples

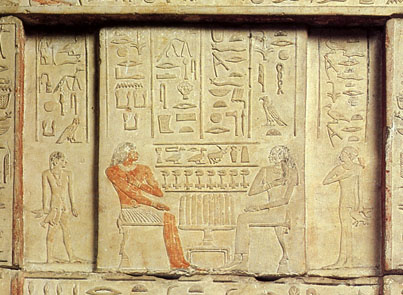

The image below is a detail from a false door (the entrance and exit for the dead person’s soul in a tomb). It comes from an Old Kingdom tomb at Saqqara (5th Dynasty, roughly 2453 BCE). The relief depicts a husband, Nikaure, and wife, Ihat, along with two of their children.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo, inventory CG 1414

The pair sit opposite each other across a table full of offerings: long loaves of bread, portrayed vertically even though they are assumed to lie on the table. The two columns above Nikaure face rightward, as does he. They give his official titles and name. The two above Ihat face left and do the same for her. The son at the left faces right, as does the text above him, and his sister, at the right, faces leftward, as do her hieroglyphs. Despite the fact that this particular door belongs to Ihat, there is a slight male bias here, since the list of offerings above the table face right, as he and his son do—the favored, “stronger” orientation for hieroglyphs and people.

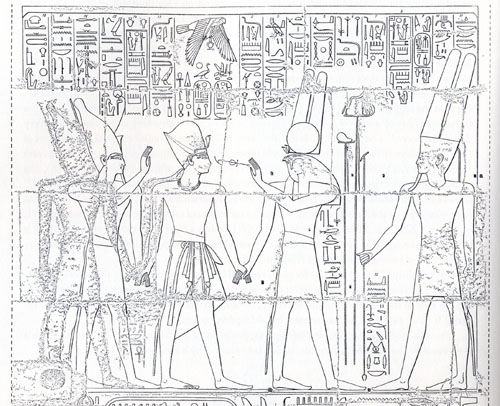

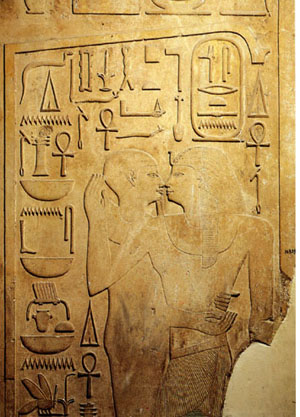

The basic conventions of Egyptian art were amazingly stable for a period of about three thousand years. We find the same principles in the Middle Kingdom. This relief (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, inventory JE 36809) on a column shows Senwosret I (12th Dynasty, reigned 1971-1929 BCE) being embraced by a statue of the god Ptah in its shrine. You wouldn’t think that statues embrace people, but pharaohs were considered divine and could communicate with gods’ statues in temples. The king is at the right, facing left. His name is in the oval cartouche above his head, and the columns of signs at either side of it give some of his titles. All face left.

The basic conventions of Egyptian art were amazingly stable for a period of about three thousand years. We find the same principles in the Middle Kingdom. This relief (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, inventory JE 36809) on a column shows Senwosret I (12th Dynasty, reigned 1971-1929 BCE) being embraced by a statue of the god Ptah in its shrine. You wouldn’t think that statues embrace people, but pharaohs were considered divine and could communicate with gods’ statues in temples. The king is at the right, facing left. His name is in the oval cartouche above his head, and the columns of signs at either side of it give some of his titles. All face left.

The rest of the signs face right. They identify Ptah and describe all the things he’s giving the king: life, dominion, stability, health, and happiness. The column at the far left is a direct quotation of the god’s words. As in these two examples, almost any relief where figures are present facing different directions, the orientation of the hieroglyphs will be determined by which one they refer to. Obviously the Egyptians considered this sort of directional consistency very important.

Facing one way, looking the other

Indeed, the directions in which figures’ faces and eyes were turned seems to have been of particular importance. It’s not uncommon for a figure to be facing one way and looking back. In that case, that figure’s hieroglyphs will face backward as well.

The relief below reveals the logic of this device very well. Two gods, Atum at the right and Montu with the falcon head (not all falcon-headed gods are Horus) are leading Rameses III to the king of the gods, Amen. (I copied this from Fischer’s book, and unfortunately he doesn’t specify where this relief is.) As they proceed, Montu turns back to hold the signs for “life” and “dominion” to the king’s face. The five right-most columns of text above refer to Amen and mimic him in facing leftward; they represent his speech to the king. The next five represent Montu’s speech and, because his eyes look leftward, so do the hieroglyphs. But not the little column of text in front of his stomach and kilt. That describes his action of leading the pharaoh to Amen, so those signs, written beside the part of his body facing right, also face right. Charmingly logical.

That sort of thing is one small part of what makes Egyptian art so appealing to me. Perhaps it gives you a better feel for why Fischer claimed that Egyptian art integrates writing and pictorial representation more thoroughly than that of any other culture. It also bolsters David’s recent entry about how studying the techniques and conventions of an artform enhances one’s enjoyment of individual artworks.

Amarna examples

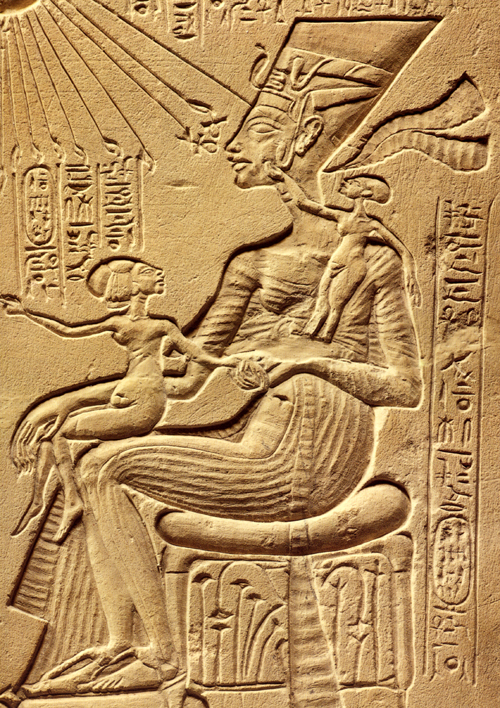

My favorite examples of head-turning reversed hieroglyphs come, not surprisingly, from the period I study, the Amarna era (18th Dynasty, New Kingdom, roughly 1350 BCE). One trait of Amarna art is its relatively casual depiction of the royal family. Previously the king had not been shown “behind the scenes,” playing with his children. Compare the Old Kingdom relief of Nikaure and Ihat, seated stiffly with their children at attention behind them, with the stela at the top of this entry. There the pharaoh Akhenaten lifts his eldest daughter, Meritaten, to kiss her. Opposite him sits his wife Nefertiti, holding the second daughter, Meketaten, on her lap, and balancing her third, Ankhesenpaaten, who stands on her arm or hip, playing with the decoration on Nefertiti’s familiar tall, flat crown. (A repaired crack has destroyed the child’s feet and some other elements of the relief). There’s a similar relief in the Louvre, by the way, where Nefertiti and at least two of the daughters sit on Akhenaten’s lap, but unfortunately only the lower part survives.

This stela is my favorite piece of Amarna art. I must confess that standing back in 1992 in the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin and studying this sentimental little image (inventory 14145) was what finally suckered me into an obsession with the art of the era. It’s not just the appeal of the family scene, though. There’s an underlying complexity and innovativeness about this piece that makes it unique in the history of Egyptian art. It’s also not just sentimental. Such a stela would have stood in a private chapel in the garden of a rich family. The fecundity and nurturing shown in the image would be seen as indicative of the pharaoh’s protective role toward his country.

As is typical of Egyptian art, each figure has a label identifying him or her. Akhenaten’s and Nefertiti’s names and titles are in the vertical columns at the top, alongside the name and titles of their sole god, the Aten, or globe of the sun, which casts its life-giving rays down upon the group. Literally life-giving, since two of the rays’ little hands hold ankh-signs to the king’s face, and another two do the same for Nefertiti. Each daughter, though, has a label identifying her, all in the very formulaic phrases used on endless reliefs for this purpose.

Here’s a detail of the part of the relief I want to focus on:

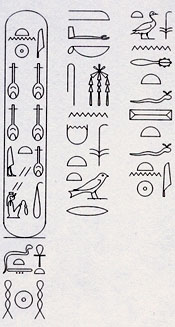

In contrast to the beautiful carving of the figures, the hieroglyphs here are rendered very badly, and it’s partly because they are so formulaic that one can read them all. I’ve used my new font program to lay them out legibly so you can see which way the inscriptions face. (The font couldn’t cram the four nfr-signs that appear side-by-side in Nefertiti’s name into the cartouche, so I settled for putting them on two lines.)

In the text running down the side, the youngest daughter is described: “King’s daughter, Ankhesenpaaten [i.e., “She who lives for the Aten”] of his body [i.e., Akhenaten’s biological offspring], whom he loves, born to the Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti, may she live forever and continuously.” The two other daughters have the same texts with their names substituted.

I’ve analyzed this stela in print, suggesting an interpretation of the brief narrative action that is going on in the scene (“Frontal Shoulders in Amarna Royal Reliefs: Solutions to an Aesthetic Problem,” The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities Vol. XXVII [1997, published 2000]: 79-98 and Pls. IV-VII). All I’m concerned with here is the fact that Meketaten has turned her head to look at her mother while pointing across at her father and sister. The short columns of text above her have been reversed accordingly:

There are other Amarna reliefs where a daughter turns her head, including one where the upper part of the princess is missing, and we can only tell she was turning to look at her mother because the few surviving hieroglyphs face the opposite direction from her feet. The reversal isn’t used in every case where a princess turns her head. In more formal offering scenes, where the princesses stand in a group behind their parents, a continuous row of short vertical columns above them gives the name and title for each. With all the rows lined up this way, the reversing of one daughter’s signs would look odd, and so the Egyptian artist kept all the columns facing the same direction. That’s another convention of Egyptian art: keep the graphic layout of the signs neat and pictorially appealing. They’re an important part of the overall image.

Reversed hieroglyphs and eyeline matches

I’m not trying to claim that Egyptian reliefs are just like film because the hieroglyphs are oriented by which was the figures are facing. There’s nothing comparable to an eyeline match in such images, since we see all the figures of a scene present at the same time, always depicted from head to toe. There is no need to match a figure’s eyeline to what he or she is looking at, since that, too, is present in the scene. There is no “offscreen space” in Egyptian reliefs.

Still, the Egyptians matched the orientation of hieroglyphs not just to the general direction a figure was facing but also to the specific eyeline created by head position. There was a logic to this, based on the fact that the direction of the gaze was deemed important and hence could be used to organize important elements of the composition of a scene—a static one in this case rather than one unrolling temporally across separate shots. That a culture so different from our own could come up with an artistic convention reminiscent of a technique in classical filmmaking suggests to me that claims about the naturalistic basis of eyeline matching and shot/reverse shot have merit.