Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel

Monday | December 19, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Our contributions to FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel continue. Last month brought Jeff Smith’s analysis of musical motifs in Foreign Correspondent and his celebration of the skill of Alfred Newman, supplemented by a blog entry here. This month it’s my turn, taking on Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata (1943; all Japanese names hereafter in Western order, family name last). My presentation is here, if you are a FilmStruck subscriber. A bit of it is available to all at the Criterion site. Today’s entry fleshes that out with some contextual background.

If the streaming version of Observations on Film Art is a bit like a bonus material on a DVD, think of these blog entries as liner notes with clips. This format allows us to tackle the films from an angle not covered in our videos. We’re sorry that not all of our readers can access the Criterion Channel. But if these entries inspire you to go back to the films in whatever form you can find them, that would be all to the good.

Conquering the self

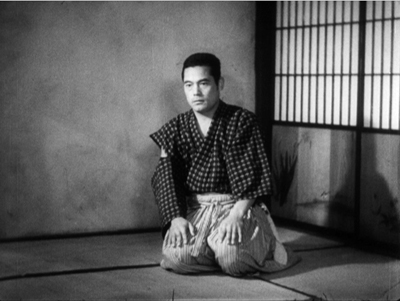

Sanshiro is a film à clef, using martial arts to promote a nationalistic cultural pride. The character of Sanshiro was based on Shiro Saigo (above), who was one of the first pupils of the founder of judo, Jigoro Kano. (In the film, Kano is called Yano, below.) Kano learned the traditional fighting technique called jujutsu (aka jujitsu). Like jujutsu, judo involves grappling, locking, and throwing, and it deploys the opponent’s force against him (or her). But Kano tried to refine the art, eliminating some of the harsher techniques, like biting and kicking, and aiming for maximum efficiency of energy.

By treating judo as a sport and encouraging sparring and public matches, Kano led judo to prominence. His pupils defeated jujutsu challengers. In 1885-1886 matches against Tokyo police champions, Kato’s star pupil Saigo proved judo’s prowess.

In the hands of Kano and Saigo, unarmed fighting techniques were turned to spiritual ends. Ju-jutsu, “flexible technique” was replaced by ju-do, “the path of flexibility”—a devotion to a way of life rather than mere mastery of grips and throws. This distinction is enacted in the film, when Sanshiro, having learned enough technique to bully people with abandon, must learn to master himself.

Judo’s emphasis on spiritual seeking fitted an ideology that emerged in the Meiji period (1868—1912). Japan’s elite was bent on incorporating Western technology and social institutions while maintaining, or rather constructing, a distinct national identity. Accordingly, jujutsu, whose origin lay in Chinese boxing, came into disfavor as part of “feudal” traditions. With young people becoming entranced by Western sports like boxing and wrestling, the government encouraged the development of judo as both modern and uniquely Japanese. As often happened, these “inherently Japanese” cultural forms were of recent invention.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

There’s another dimension to the story. John Dower has pointed out that imperial wartime propaganda tended to emphasize not triumph over the enemy but the need to purify the self. Accordingly, judo’s victory in the social sphere parallels Sanshiro’s conquest of his anger and egotism.

In the film, Sanshiro comes to Tokyo in 1882, the year Kano actually founded his school. After training, both physical and spiritual, the young man proceeds to defeat the surly jujutsu master Monma. Bristling with youth and vigor, Sanshiro then comes to represent a rising generation capable of surpassing its elders. The next fight references Saigo’s most famous combat during the 1886 police tournament. He must defeat the kindly jujitsu master Murai. But he is attracted to Murai’s daughter Sayo, and so it pains him to trounce her father. But Murai acknowledges judo’s superiority and easily forgives Sanshiro. Judo, he says, awakens his senses.

Most intently, Sanshiro’s purity of spirit clashes with the foppish, Europeanized Higaki, who exploits judo for aggression and self-aggrandizement. Their big fight comes on a wind-swept hillside, perhaps a reference to Saigo’s signature technique yama-arashi (“mountain storm”). The polarity Japanese/ Western would become even stronger in the film’s sequel, Sanshiro Sugata II (1945), in which Sanshiro must fight an American boxer. But from fight to fight, Sanshiro gains greater and greater self-possession, so that in the climactic combat, he can spare time to stare at clouds and envision lotus blossoms.

The film’s plot reverses Saigo’s actual life course: He became a street brawler after he won his tournament victories. More basically, Sanshiro Sugata goes beyond its historical sources and political program, as ambitious films tend to do. Nationalistic messages appropriate to wartime are transformed, reworked—”cinematized”—through Kurosawa’s remarkably dynamic approach to film style.

A resumé film?

Sanshiro is a young man’s first film. Kurosawa started on it when he was thirty-two (within my magic-number deadline). In the Criterion Channel video, I treat the movie as an occasion for an ambitious director to display his versatility—a sort of resumé film, as we’d say nowadays, and maybe a little showoffish.

He was ready for the project. He had a busy several years as an assistant director and screenwriter at the fast-moving Toho studios. He worked on twenty-eight dramas and comedies between 1936 and 1942. When he read Sanshiro’s source novel upon publication, he urged Toho to buy it, and he plunged into his project with fervor.

Like other young directors in Japan, he was well aware of developments abroad. His autobiography records seeing many imported films, from Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930). Interestingly, he claims to have seen Storm over Asia (1928), Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher (1928), Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and even films by Buñuel and Man Ray. His viewing included Hollywood fare by Ford, Lubitsch, Borzage, Wellman, Sternberg, and others. Indeed, he could have kept up with American cinema right up to Pearl Harbor; prints of Edison the Man (1940), Morocco (1930), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) seem to have been playing in Tokyo in late 1941. Then all American films were banned.

So he was a cinephile director, perhaps not quite as passionate as Ozu, but a young man who looked and learned. Like most Japanese directors, he had mastered Hollywood continuity staging and cutting. I’ve argued elsewhere that many of his contemporaries were bolder stylists than the Americans. Whether it’s a matter of long takes, camera movements, rapid cutting, or subtle transitions—the Japanese found their own striking innovations.

Ozu’s distinctive 360-degree staging space, low camera height, and play with graphic editing constitute an extreme example of Japanese pictorial invention, but he wasn’t alone. Take this passage from Naruse’s Street without End (1934). The heroine has left her husband’s hospital bed after denouncing him, his mother, and his sister for selfishness. Servants and family rush past her; he may be dying. She hesitates in the corridor. Should she return?

The pattern of cuts and frame entrances accentuates her uncertainty—taking a step, and halting—while the clashing directions in which she moves (right, left, right) have a Soviet-montage flavor. So do the blank frames at the start of every shot, since we have no idea of where we are in the corridor, or where she is, until she thrusts into the frame. And we don’t know whether she chooses to return or not; the geometrical cutting expresses her hesitation.

This geometrical approach to editing is one of the characteristics of Sanshiro I discuss in the video entry. You see it near the start, when alternating single shots of Yano, back to the river, are intercut with slow tracking shots across Monma and his truculent students. To push the pattern further, the tracking shots alternate—first in one direction, then another. Like two rhyming lines in poetry, each of these cinematic couplets brackets one futile attack on Yano after another. Later fight scenes will get more complicated, but display no less rigorous a patterning. And the purpose is always to add to the tension and excitement of the combat.

Another sort of pattern we find in Sanshiro is simpler, but Kurosawa works some nifty variations on it. It’s also somewhat geometrical, but it serves mostly to accentuate a moment of stillness. This is the axial cut, the shot change that moves in or back along the axis of the camera lens. The effect is of sudden enlargement or de-enlargement, a popping out toward the viewer or a sudden withdrawal. Like most directors, Kurosawa uses the axial cut to enlarge something–here, Sayo’s act of praying for her father at a temple.

When the axial cut is justified as a character’s viewpoint, it has the effect of signaling a sharp narrowing of attention. This happens here, when we realize in the voice-off remark (“How beautiful”) and a fourth shot that Yano and Sanshiro have come upon her. That exemplifies an axial cut that moves backward rather than inward.

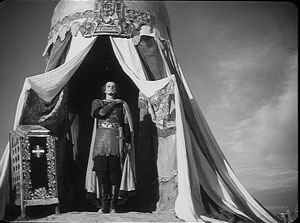

I discussed Kurosawa’s fondness for axial cuts years ago, but it’s interesting to see their origins here. They’re present from the earliest years of cinema, but Kurosawa, again like the Russians, used them expressively. Most uses in Hollywood consist of just two shots, a long shot and then a closer one on the camera axis. But the Soviets, perhaps starting with Eisenstein, multiplied the number of shots and made them fairly brief, so the effect is of a person or object punching out at the viewer. Eisenstein uses the device throughout his silent films, but in both Alexander Nevsky and the two parts of Ivan the Terrible, he develops the device in a very virtuoso manner. Here’s Ivan, standing above the battlefield.

Eisenstein adds to the popout effect by cheating Ivan’s position between shots, so he jumps forward out of his tent.

I’ve found some axial cuts in Japanese films before Kurosawa started directing. One of the most “Kurosawa-ish” comes in a minor 1939 Nikkatsu swordplay film called Faithful Servant Naosuke (Chuboku Naosuke). Again, the cut-ins emphasize a poised moment.

Even if Kurosawa didn’t invent the technique, he made it more prominent and percussive in Sanshiro. It makes the pauses within combat as staccato as the action of fighting. I spend some time in the video talking about how this all works in particular scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, The Most Beautiful (1944), itself a real beaut, uses the technique quite differently, mainly for tension. His later films continue to explore its possibilities. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 (1945) resorts to the device to express our hero’s lingering departure for the big duel. He trots toward us, and each time he pauses to look back, Sayo bows.

Today’s filmmaker would probably pull us back with a tracking or crane shot, but by relying on editing Kurosawa gives us his typical crisp geometrical patterning. The abrupt cuts underscore Sanjuro’s realization that he may not return from this life-or-death confrontation. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2, along with the first film and The Most Beautiful, is available from Criterion, as a disc and on FilmStruck streaming.

My streaming presentation discusses other cinematic strategies Kurosawa employs, but these remarks should give you a sense of just how energetically creative he’s being in his first film. It’s a very flashy item, and it looks far into the future. Decades of kung-fu films have been based on dueling dojos, rival fighting methods, and escalating challenges. In addition, Kurosawa’s technique, moving lightly under the weight of an official message, seems very modern.

Youthful, too. As he told Donald Richie, “I really make my films for people in their twenties.”

The information about the history of judo comes from Gabrielle and Roland Habersetzer, Encyclopédie des arts martiaux d’extrême orient (Amphora, 2000), 265-268, 300-301, 549, and 765. Kurosawa lists films he saw in his youth in Something Like an Autobiography, trans. Audie Bock (Knopf, 1982), 73-74. John Dower’s discussion of Japanese propaganda is in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1987). The closing quotation comes from a 1962 conversation reprinted in Akira Kurosawa Interviews, ed. Bert Cardullo (University of Mississippi Press, 2008), 8. Thanks to Hiroshi Komatsu for information about Faithful Servant Naosuke.

Street without End is available in the Criterion Eclipse collection Silent Naruse. If you don’t have this set, get it pronto.

Informative books about Kurosawa and Sanshiro include Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa third ed. (University of California Press, 1999); Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, rev. and exp. ed (Princeton University Press, 1991); and Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune (Faber, 2001). Especially revealing about Kurosawa’s production methods in his later films is Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). On the “spiritist” trend in government policy in the media of the period, see Peter B. High’s magisterial The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), Chapter 6.

For more on axial cutting in Soviet and modern films, and The Simpsons, go here. I discuss Eisenstein’s axial cutting in The Cinema of Eisenstein, Chapters 2, 4, and 6. On Ozu’s characteristic staging, shooting, and editing system, see my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available for download from the University of Michigan Library site. The full PDF takes a while to download, but you can get access quickly by clicking on “List of all pages.” I discuss other aspects of the tradition from which Kurosawa comes in Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 12 and 13. See also the Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Shimizu entries on this site.

Kim Hendrickson, Criterion producer, and Grant Delin, DP, filming DB from a closet.