Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement . . . .

Friday | April 7, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

A Quiet Passion (2016).

DB here:

. . . . sums up what has happened and hints at what’s to come.

Seeing Terence Davies’ splendid A Quiet Passion again at our Wisconsin Film Festival brought out several subtleties I hadn’t registered on my first pass last year at Vancouver. Among the things I appreciated was a poignant 360-degree-plus tracking shot in the Dickinsons’ parlor.

This poet’s passion isn’t always so quiet. Davies’ earliest films are notably light on dialogue, but this one contains plenty of talk, both bantering and brutal. Perhaps most surprisingly, the supposedly withdrawn Emily Dickinson engages in snappy and snappish exchanges with friends, family, neighbors, and one awkwardly sincere suitor. All the more striking, then, when Davies halts the talk and gives us a suite of images accompanied by discreet sound effects, music, and voice-over portions of Dickinson verse.

Fairly early in the film, we get a spirited exchange between the censorious Aunt Elizabeth and the Dickinson family. After her indignant reply to their mock-heathen teasing, she gulps down some currant wine. Next we see the family quietly sharing an evening. That’s when we get this ripe circular camera movement.

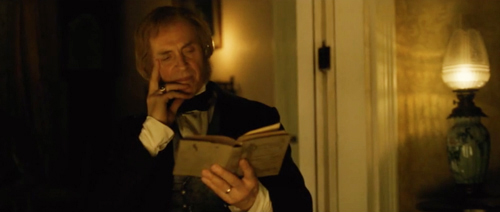

It starts framing Emily, reading by firelight. She looks left.

As the camera coasts past Emily we get a glimpse of a fond smile. The moving frame reveals Aunt Elizabeth, struggling to keep her eyes open.

In the course of this movement, over the soft crackling of the fire and a ticking clock, we hear the older Emily’s voice-over reciting.

The heart asks pleasure first,/ And then, excuse from pain;/ And then, those little anodynes/ That deaden suffering.

The poem is a famously puzzling one. Is the speaker suggesting a bargain–if not pleasure, then no pain, please? Or is it a description of the course of a life: youth seeking pleasure, old age willing to accept absence of pain, and in the end a plea for something that simply ends suffering? The juxtaposition of young Emily and aged Elizabeth suggests two phases of woman’s life: Is Emily still pledged to pleasure (of a bookish kind) while her aunt is already seeking an anodyne, like the brandy she greedily gulped and the sleep that seems to be stealing over her?

As the camera passes Aunt Elizabeth, the poem is completed.

And then, to go to sleep;/ And then, if it should be/ The will of its Inquisitor,/ The liberty to die.

Elizabeth’s drowsiness comes to prefigure the death that will haunt the rest of the film. And the poem’s grim acceptance of physical decline, lifted by the mercies of death, sketches what will be all too vivid in scenes to come.

The camera continues its leftward survey of the family circle, settling next on Emily’s father Edward. He’s thoughtfully reading. So is brother Austin, at the rear table. Sister Vinnie, though, is sewing at the same table.

This survey of the immediate family shows Emily, like the men, gone all literary, while good-hearted Vinnie does no reading, instead attending to women’s tasks. The shot identifies Emily as, if not unfeminine by the standards of the day, at least not sunk in domesticity. She may be searching for that literary spark she will so often identify with glimpses of Eternity.

The view of Edward has been accompanied by clock chimes, and under the image of Austin and Vinnie we hear the clock start to strike the hour of nine. As the camera moves leftward, we see the mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson.

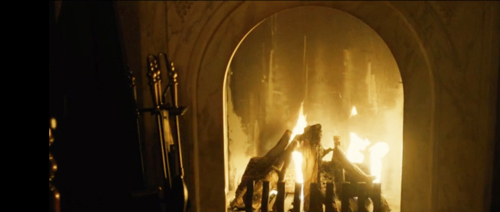

Neither reading nor tending to domestic tasks, Mrs. Dickinson is staring raptly into the fire. Everyone is in a kind of reverie, but hers is inward and melancholy. In the previous scene she has told Aunt Elizabeth “I prefer to listen and remain silent.” Later in the film we’ll learn that she has gradually withdrawn from the family, as if feeling ill-adjusted to these intellectuals, or through some private unhappiness. Later in the scene we’ll get another hint, but after briefly lingering on her, now the camera moves to the fire and then passes beyond.

The piano will be the site of a crucial conflict to come, and the wine decanter, already featured in the scene before, will later be one index of the self-righteousness of the new clergyman’s wife. This “empty” stretch becomes a caesura before we get to the simple, devastating final image of the shot.

So much for books. Emily’s plaintive look, not clearly fastened on any family member, is ambivalent. Has the camera traced her eyes around the family circle, as her sidewise smile at Aunt Elizabeth suggested earlier? If so, what has moved her? Her mother’s solitude? Her siblings’ and fathers’ obliviousness to the older woman? Or is it something more self-centered? Locked within the family circle, has she surveyed the perimeter of her life to come?

The question is partly, teasingly answered, when we hear the offscreen voice of Mrs. Dickinson. She asks Emily to play one of the old hymns. Emily rises and goes to the piano, and we get a cut to the shot surmounting today’s blog entry. After Emily starts playing, the rest of the family is forgotten, and Davies cuts to a closer view of her mother.

Still staring into the fire, she speaks of hearing the hymn sung by a young man with a beautiful voice. He was only nineteen when he died, she tells us, or maybe just herself. The softly delivered memory carries more than mere nostalgia. Are the others even noticing? We never find out.

Unlike her husband and children and Aunt Elizabeth, the mother ponders the past and its losses. We’re invited to imagine an alternative life for her, perhaps with the beautiful young man. Is he kin to the young woman in white with the parasol recalled by Bernstein in Citizen Kane, as he stands before his roaring fire? At the least, this warm parlor is now haunted by death.

Davies is too tactful to push this moment, leaving the character to keep her own counsel. But I can’t resist another probe. The Magnificent Ambersons is one of Terence’s favorite films, he told us during his visit (“better than Kane“). It’s not a stretch to let the image of Mrs. Dickinson remind us of the somber shot of Major Amberson before another fireplace. Deprived of his fortune, baffled by all around him, he ponders the origins of life as the narrator muses that even an Amberson might not get a leg up in the Hereafter.

Terence pointed out to us that the great American films are often about families, because in that setting passions are both aroused and contained. The Dickinson family, tightly bonded by love and respect, ruled by a tender but iron-willed patriarch, harboring a mother and daughter withdrawn from the world, split by failed marriages and angry reproaches, prey to death and broken pledges, is no perfect haven. Perhaps Emily’s stabbing epiphany is a realization of all of that, and what it might mean for her art. All this takes two minutes and ten seconds.

Nowadays the circling camera is a cliché; characters sitting around a table or even just standing in the street seem to be spinning on a turntable. Davies is far more discreet and precise. Step lightly on this narrow spot, a Dickinson poem advises us, and that’s what his camera has done here.

Thanks to Bianca Costello and Music Box Films, which is distributing A Quiet Passion. Its US rollout starts 14 April. Thanks as ever to the Wisconsin Film Festival and its plucky programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

And many thanks to Terence Davies for coming to town and providing fine conversation about George Butterworth, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the making of A Quiet Passion. As he told our audience: “I hope you enjoy it, and if you don’t, complain to Mr. Trump.”

Other entries in the intermittent Sometimes. . . . series are here (I Topi Grigi), here (The Mormon’s Victim), here (A Touch of Zen), here (Side Street), and here (Frisco Sally Levy).

Kristin and Terence Davies.