The movie experience as format: A 3D state of the union

Saturday | March 16, 2019 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

On February 13, the day after I posted my blog entry, “3D in 2019: Real Dvided?,” I received an email message from Belgian film critic David Vanden Bossche. He had been intrigued enough by my post to investigate the number of 3D screenings on offer in Belgian cinema chains in comparison with “standard” or “premium” 2D screenings. I had found 3D screenings the distinct minority in our local Madison theatres, even early in films’ runs. David found the opposite in Belgium

To extend his investigation, David enlisted his colleague Tim Bouwhuis to analyze the proportions of 3D screenings in the Netherlands.

David and Tim’s resulting online article, “Filmbeleving als Format: A 3D State of the Union,” was posted on March 13 on Enola.be, a film and music site in Flemish. David kindly offered to send me an English translation of the piece. It turned out to be quite intriguing, since 3D in Belgium and the Netherlands is considerably more robust than in the US. I mentioned in my post that areas of the world outside North America have a higher proportion of 3D-equipped screens than we do here. The attention usually focuses on the Chinese market’s enthusiasm for 3D. This enthusiasm is often credited with encouraging Hollywood studios to keep making 3D films despite their waning popularity in North America. But other countries favor 3D as well, and it’s valuable to have an examination of a pair of small European markets.

Our thanks to David and Tim for allowing us to present their article here as a guest post.

On 12 February, following the American premiere of Alita: Battle Angel, Kristin Thompson posted a new entry, 3D in 2019: Real Dvided? Thompson investigated the state of 3D within the contemporary theatrical environment in the United States. Her conclusion was crystal clear: 3D’s share within American movie screenings has steadily declined in the last decade, when Avatar urged most theatre chains to make the switch to 3D projection. The numbers Thompson presents abundantly show that American multiplexes are less and less inclined to include large numbers of 3D screenings in their programs, and that 3D is losing ground to another ‘premium’ format such as IMAX.

Those findings were intriguing enough suggest a closer look into the Belgian situation. Because that is ultimately a small market, I contacted fellow film critic Tim Bouwhuis, who lives in the Netherlands and could thus provide some information on the particular situation in his home country. Our research allowed us to collect an acceptable amount of material and provide us with numbers that paint a rather different picture than the one to be found in Thompson’s piece. The data we collected show a different evolution for 3D in these two countries and possibly in the whole of Europe. Further research could shed some light on this. Even a limited study, however, offers some possible explanations for these differences. This entry will tackle some of them.

United States: RealDvided

Before dealing with the situation in Belgium and the Netherlands, it is probably a good idea to summarize what Thompson presents in her piece.

Starting with screenings in her hometown Madison, Wisconsin, she observes that 3D’s share in the number of screenings of recent blockbusters is surprisingly limited. Thompson broadens the scope with additional numbers from other cities, concluding that this is definitely not a local issue.

The growth in 3D emerges with the success of Avatar and the consequent peak in 3D earnings in 2010. Since then, 3D’s share of film grosses has been in decline. Production of 3D television sets – a prime feature in store windows just a few years ago – has all but halted. Even if one should exercise some prudence in declaring the death of 3D in a theatrical environment, it is safe to state that its intrusion into the living room has failed spectacularly.

It is remarkable that other ‘premium formats’ (Thompson refers to these as PLF – Premium Large Formats,’ a term we will stick with here) such as IMAX or various “ultra” and “grand” large-screen auditoriums (usually offering extra comfort and superior sound) are gaining in popularity, while 3D is on the decline. That means the public is willing to pay extra for a ‘premium’ – PLF upcharges are as high or higher than those of 3D – and apparently often prefers to pay for PLF rather than for 3D. This process obviously suits the theatres’ economic agenda: a large part of the extra income returns to the distributor and – as Thompson points out – there’s also the extra cost for 3D glasses. The upcharges may also make the visitor less inclined to spend money on food & beverages, a vital source of income for theatres. That means the final balance might be rather negative from the theatre’s point of view in the case of 3D revenues. The fact that PLF’s may net a larger profit thus adds another extra factor working against 3D.

One might expect that in case of Alita the figures would be rather different. The film is produced by James Cameron, one of 3D’s most prolific advocates and arguably one of the few directors – along with Ang Lee, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Gan Bi and (even) Jean Luc-Godard–who actually tried to explore the true potential of 3D’s formal cinematic language.

The numbers Thompson presents, however, show that even an “event” film such as Alita does not always encourage US theatre owners to schedule more 3D screenings. Thompson points out that there might also be a more practical issue at work here: the clarity of the image is one of the more troublesome issues 3D faces. To solve this, Cameron and Roberto Rodriguez (who took the directing honors when it turned out Cameron was too busy preparing the Avatar sequels) made sure the DCP’s (digital cinema package, used to send movies to theatres since the disappearance of film stock) came with a set of guidelines. These technical complexities, combined with pricey investments and low returns, make for a cocktail that encourages theatres to drastically cut back on the number of 3D screenings.

Belgium: The Kinepolis experience

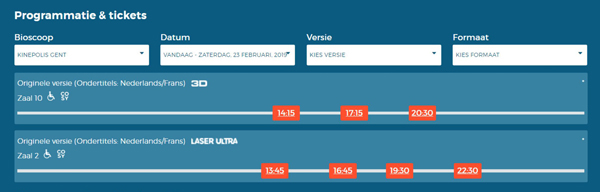

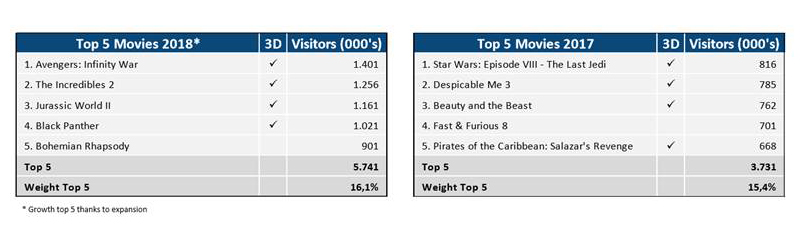

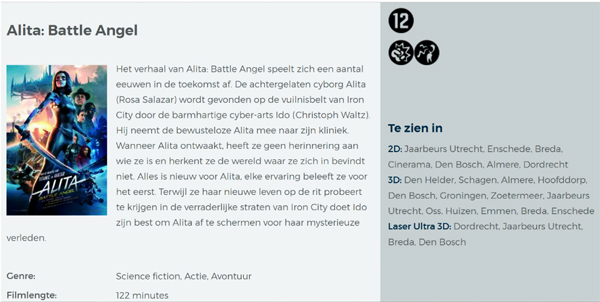

Intrigued by Kristin Thompson’s article, I gathered comparable statistics for Alita in Belgium. See the top image for an ad listing the formats available during the first week of release at Kinepolis Group theatres in Belgium.

That’s a lot of 3D ! No fewer than four of these six formats integrate 3D into the theatrical experience. Obviously, a film such as Alita is likely to receive such a treatment and definitely during its first week. It is also necessary to look – as Kristin Thompson did – at the relative percentage of 3D versus “standard” 2D screenings. A ten day interval seemed ideal to reassess the situation. Here are schedules for two Kinepolis theatres ten days after the film’s opening.

As it turns out – depending on the Kinepolis theatre one chooses to visit – 3D still makes up between 42 and 67 percent of Alita’s daily screenings. The highest number is reserved for Kinepolis Brussels, with the theatre being the only one equipped with a full-fledged IMAX screen. IMAX as a PLF in Belgium is used exclusively for 3D screenings, save for some very rare exceptions.

As pointed out already, Alita can be regarded as an exceptional production that integrates 3D as part of its raîson d’être and its promotion. Alita’s figures might be exceptional, so looking at a comparable title might be necessary. The Lego Movie 2 made its debut about three weeks later, is also shown in 3D and thus makes for a perfect comparison.

3D’s share is smaller here, but still 40 percent of the screenings are in the 3D format, a number well above the American averages.

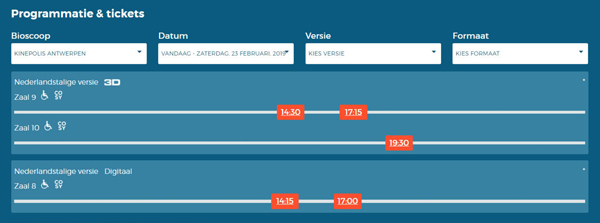

Because two titles might still represent a distorted sample, we contacted Kinepolis Group Belgium and asked them to provide us with some material that would allow to have a better general idea about the significance of 3D within their total number of screenings and their profits and the way this share has evolved (or is evolving).

These numbers are clear enough to allow some conclusions. Both in 2017 and 2018, 4 out of 5 of the most popular films for Kinepolis Belgium were 3D movies. 2018’s numbers even show that both the relative share and the absolute numbers (and thus the weight of the top 5 and 3D) are indeed increasing. Obviously that does not mean that every paying visitor opted for 3D (or one of the various combinations of 3D and PLF), but as the general share of 3D screenings for every movie released in this format at Kinepolis theatres in Belgium is situated anywhere between 40 and 60 percent of the total number of screenings. That means this percentage can be applied to these numbers.

The Kinepolis representative pointed out that the percentage of 3D screenings for a movie is determined on the basis of the quality of the 3D imagery and the way the 3D format enhances the viewing experience. Alita is perceived to be a prime candidate for these arguments and thus the number for 3D screenings is very high and at the lower end for The Lego Movie 2. Even if one sticks to the lower end of the scale, however, the importance of 3D screenings within the total number of screenings is still remarkable.

Beyond Kinepolis

All those results lead to a single clear picture: unlike the American situation, 3D is still positions itself as the preferred “premium format” in Belgium. Its impact on the total number of screenings (in Kinepolis theatres) is still very significant and shows no signs of diminishing.

I believe there are a few elements at play to create this situation. One of the first emerges when we take a look at the Alita screenings outside of Kinepolis theatres. Another large chain of theatres, UGC, provides a useful comparison. (Most independent movie houses have not screened Alita). The schedule immediately below is for a UGC cinema in Antwerp, and below that, one in Brussels.

In Antwerp there is not a single 3D screening to be found; in UGC Brussels, there’s just one, while the same day lists 8 standard screenings. The discrepancy between these numbers and the ones at Kinepolis are easily explained: UGC has a very limited number of 3D screens.

Slowly it becomes clear that the very specific situation of the Belgian movie theatre environment is an important factor in all of this.

Kinepolis Group was formed through the joining of two large family companies, the Claeys & Bert Groups. At the start of the 19080s, they began setting up a chain of theatres that no longer consisted of the smaller movie theatres Belgium had known up to that point. Their theatres introduced multiplex to the country. “Decascoop” in Ghent (first 10 screens, with two added later) and the other early Kinepolis theatres benefited from the rise in ticket sales in the early eighties and consolidated their position by being the only theatres around the country able to show box-office hits such as E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial and the “Indiana Jones” trilogy, on multiple screens. 1988 saw the inauguration of Kinepolis Brussels – at that time one of the largest theatres in Europe – along with the first IMAX screen in the country (and most neighbouring countries).

At that time though, IMAX was a used only to screen spectacular documentary films that offered the sensation of flying through the Grand Canyon, diving into the ocean or being in outer space. Production of these films was rather limited. When the audience started to lose interest, Kinepolis halted its programming in 2005, just when the US market was taking its first steps towards IMAX screenings of regular releases. Christopher Nolan’s films were instrumental in the process that eventually turned IMAX into a popular “premium format.”

More or less simultaneously 3D resurfaced. The format enjoyed some popularity during the fifties (Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder comes to mind) and returned in the early eighties, blessing film history with a few horrendous films as Jaws 3D and Friday The Thirteenth – Part III 3D. The more recent revival of 3D gained impetus with the releases of animated films, notably The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005) and was given a boost by U23D (2008). Other animated and concert films followed, but it was Avatar, with its combination of 3D with the latest state-of-the-art special effects technology, that pushed theatre owners to convert their screens to digital projection, the necessary prerequisite for add-on 3D capability. Its huge success started an evolution that promised the full potential of the 3D cinematic language would finally be explored. When Scorsese, Lee, and Godard took up experiments, it even briefly seemed this would actually be true.

In the US, although Cameron’s smash hit dictated the rapid spread of 3D technology, the format still had to face competition from the already established IMAX format. That was not the case in Belgium or the Netherlands. Kinepolis Group – the dominant chain by now – solely promoted 3D, and this position dictated the whole theatrical environment. The IMAX screen reopened in 2016, when 3D was well established as the preferred premium format. IMAX was (and is) used almost entirely for 3D screenings.

It is necessary to include another element here: the exceptionally high projection standards at Kinepolis Group. When John McTiernan came to Brussels in 1988 to launch Die Hard, he claimed that there was probably no better projection of his film to be seen anywhere in the world. Those might have been the words of an overly enthusiastic director, but they illustrate the high technical standards within Kinepolis Group. Other theatre chains were more or less forced to follow suit.

Because quality projection became the standard, any other “premium” format faced a high hurdle when it came to distinguishing itself. “Laser Ultra” already offers an exceptional viewing experience on a very large screen, so further investment had to be justified by something beyond image quality or a larger screen. 3D offered such a distinctive element and extra added value and initially did not face any competition from PLF’s. When that changed, Kinepolis kept promoting 3D, with combinations: “Laser Ultra 3D” and “4DX,” which adds vibrations to the experience.

All of the above means that 3D’s position in the Belgian environment is very different from its position in the US. Obviously Kinepolis also needs to pay the distributors, but a new deal with RealD on the use of 3D glasses consolidates Kinepolis’ position and intensifies their efforts to promote 3D. All of this means that the format will remain popular in Belgium. In this way, Kinepolis Group’s market position also dictates 3D’s standing as the preferred “premium” format in Belgium.

The Netherlands: Experiences & attractions

The Kinepolis Group is also a dominant factor in the Netherlands, which makes comparing the situation in both countries an interesting endeavour. The Netherlands’ theatrical environment has two major chains, Pathé and Kinepolis, both of them part of larger European concerns. Pathé is part of the French group ‘Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé’ – a company that has its roots in the early days of cinema. Pathé owns 28 theatres, spread out over 20 Dutch cities. Kinepolis is a branch of the Belgian company and owns 17 theatres in the Netherlands.

With 21 theatres, “Vue Nederland” also deserves to be mentioned, although their total seating capacity is rather limited and has its main focus on smaller provincial towns.

The rise of new technologies, PLFs and “extra” movie attractions such as 4DX, has lead to a situation in which standard screenings have become something of a curiosity in the multiplexes of most major cities. Almost every theatre in a major city boasts 3D, Dolby Atmos or another premium feature. Developments in sound and imagery are promoted: Pathé even distinguishes between Dolby Atmos and Dolby Cinema, with the first emphasizing immersive sound.

Six IMAX screens are spread throughout the country, although most of them would not stand up to a purist’s scrutiny: the largest one – Pathé Arnhem – measures 21×12 metres, whereas a standard IMAX screen is supposed to be at least 22x16m. The Dutch IMAX venues pale in comparison to Brussels’ enormous 27.6 x 19.3 screen.

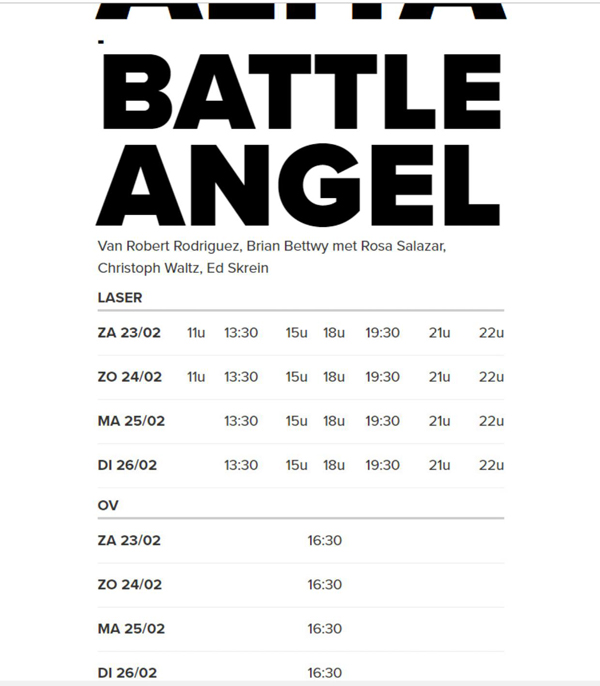

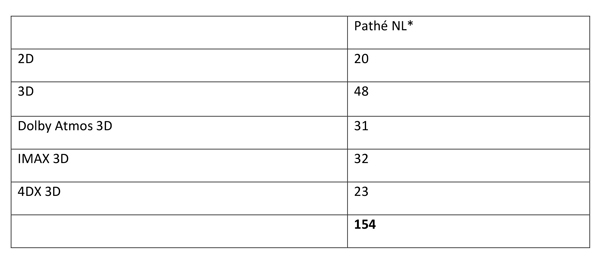

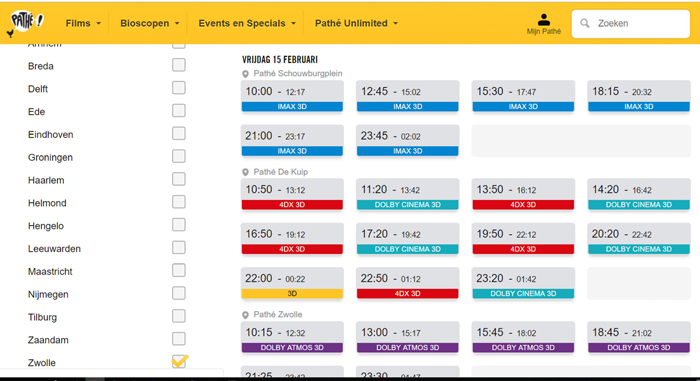

This variety of screens, systems, and venues makes it difficult to get a good grip on the partition of different formats, so once again we turned to specific Alita screenings available on February 2, 2019 :

At first glance, standard 2D and 3D screenings are balanced by premium screenings. That perception changes, when we take into account that only 5 out of 25 theatres feature 4DX, 5 offer Dolby Atmos 3D and 6 offer IMAX. That means that in some theatres it has become all but impossible to see a standard 2D screening.

The most important factor here is the fact that theatres that offer 4DX/Dolby Atmos 3D/IMAX, focus almost entirely on these formats. Those theatres are usually situated in larger cities, thus rendering it almost impossible to see a standard screening there. Amsterdam/Rotterdam (see above and below) are prime examples: out of 44 combined screenings only three of them are standard screenings. In Scheveningen, Maatsricht or Eindhoven there are no standard screenings to be found at all on the same day.

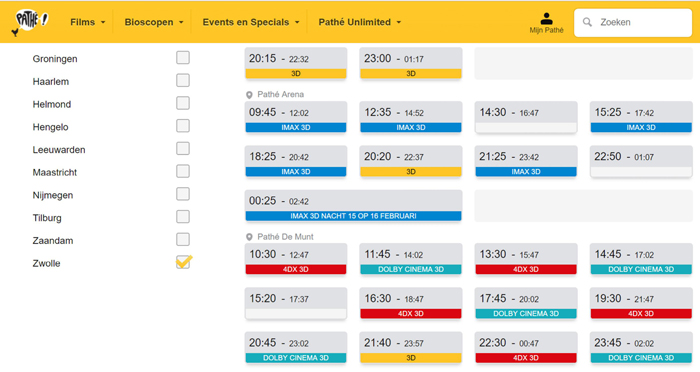

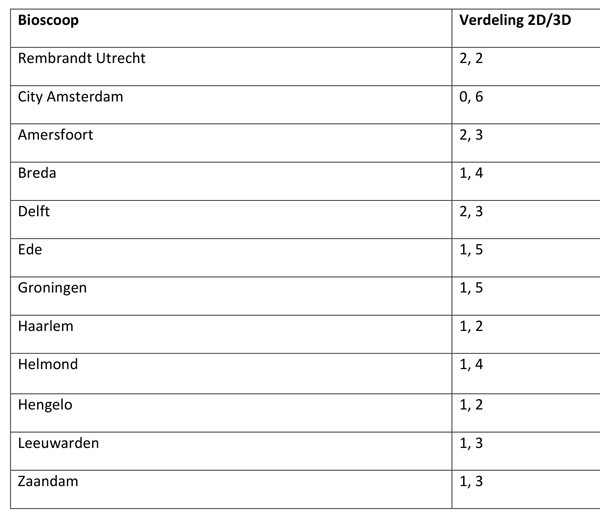

Most theatres are still located in smaller cities, and a general overview would thus suggest a rather balanced field of standard and 3D screenings. But even in those smaller venues – that do not offer the extra attractions 4DX, Dolby Atmos 3D or IMAX, the 3D screenings still outnumber standard screenings (see below)

3D vs 2D in theatres without 4DX, Dolby Atmos and/orIMAX as of February 15, 2019:

With 1 out of 3/3/4 , it is clear that 3D screenings are dominant in Pathé theatres. Even daytime screenings on weekdays are 3D, which relegates standard 2D screenings to the position of a rarity.

Kinepolis’ available number of formats in the Netherlands is more limited than in Belgium. Neither IMAX nor 4DX is an option here. For Alita that results in:

The Vue chain competes with Kinepolis and Pathé in offering DX theatres that combine Dolby Atmos with superior projection technology. As in Belgium, the dominant chain sets the technical standard. A select number of theatres offers D-Box chairs that move with the action on screen. The American film critic Jeffrey Wells describes D-Box chairs as “4 DX’s less dynamic cousin.” (D-Box is Canadian in origin, while 4DX is South Korean).

Pathé, Vue and Kinepolis promote their different PLFs in exactly the same way, using “experience” and “immersion” as unique selling propositions. With 4DX the movements and effects start competing with the images for the viewer’s attention, returning the cinematic experience in a ironic way to its attraction-based origins when it was something to be experienced at fairgrounds and other shows.

In sum, the Dutch theatrical environment resembles the Belgian. A high technical standard has become the zero-line for movie screenings and 3D has penetrated the market to such an extent that it is no longer perceived as being a “premium” format, which leads to a set of various attraction-based formats that try to justify the extra cost.

At this point Dolby Atmos, Imax, and 4DX are still perceived as novelties, but it is likely that exhibitors will need additional attractions in years to come. Rising admissions for PLFs and anything “premium” suggest that visitors are constantly looking for more immersive experiences (according to the “Dutch Foundation for Film Research” in their 2018 yearly review). The number of available PLFs has significantly risen in the last few years and as long as the dominant chains continue to invest in these formats, others will follow suit. Kinepolis and Pathé set the standard, competing chains adapt.

Whether or not the public is actually asking for these technologies remains a topic open to discussion. One could claim the public merely adapts to the industries’ innovations. Still, there is no denying that PLFs turn a large profit. In Pathé Rotterdam the regular ticket price for PLF is 18 euros, while a standard screening will cost you 11 euros. Despite the cut that needs to return to the distributors, the cost for 3D glasses, and the “hardware” investments, 3D in all its forms is dominant when it comes to movie screenings in the Netherlands. The late entry of IMAX into this environment (as in Belgium and contrary to the US) meant 3D had little or no competition and consolidated its position as the preferred “premium” format.

These conclusions to come with some nuances. The Dutch part of this piece limits itself to one title and three dominant chains. Independent movie theatres were not addressed and obviously Alita: Battle Angel has some standard screenings outside of the major theatre chains. There is enough conclusive evidence, however, to support the claim that standard screenings have all but vanished in the larger cities.

A publicity image for Kinepolis, Brussels.