Vancouver: First sightings

Sunday | September 27, 2020 open printable version

open printable version

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

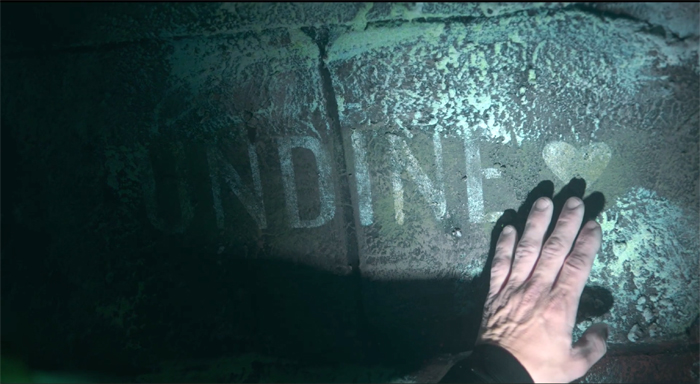

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).