Books worth fondling, if you can lift them: The rise of the Massive Auteur Monograph

Sunday | December 13, 2020 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

The fears that electronic publishing would kill off the physical book have abated. Just as home video and theatrical moviegoing managed to coexist, readers seem to have divided their commitment between e-books, to be read on the go or tapped into for certain purposes (cooking, exercise, reference), and books they want to have and to hold.

Publishers have noticed. They’ve realized that sumptuous books have their own appeal, and art books and de luxe editions continue to be printed. With the rise of digital publishing, one editor notes, “Hardback books have to be more beautiful., better produced, and a pleasure to handle. The market for books worth fondling is bigger and expanding.”

This conviction is affirmed by a trend that I’m sure you’ve noticed. We’ve long had fancy picture books devoted to film; the first one I owned was The Movies, by Arthur Mayer and Richard Griffith, from 1957. The Big Movie Picture Book is a long-lived genre, devoted to personalities, periods, and the making of classics like The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

But the trend I have in mind is different. It’s the de luxe book dedicated to a director, with documents capturing the creative process and texts written by serious critics. Call it the Massive Auteur Monograph.

Massive because it’s high, wide, and handsome, as well as heavy. Some of these books are monstrously big, and all boast coated paper and production design suitable for a book on any of the fine arts.

Auteur because it pursues the idea, now commonplace, that the director is the central creative figure in much filmmaking.

Monograph because it’s not just an anthology but rather a through-composed argument about the significance of the auteur in question. Even when the book compiles texts by several hands, those texts form part of a coherent “database” sprawling across the big pages.

In art publishing, books like this are a staple, often attached to particular exhibitions or museum collections. And we’ll see that there are some forerunners of these cinematic “art monographs.” But now I think we’re seeing the MAM come into its own.

Just this year we’ve had three major additions to the stack: the Taschen boxed set devoted to Jacques Tati, Adam Nayman’s book on Paul Thomas Anderson (Abrams), and Tom Shone’s study of Christopher Nolan (Knopf). Each deserves in-depth discussion, but I can’t do justice to that here. This isn’t a review. Instead, these books set me thinking about how we got here, and what “here” looks like. I want to consider how film criticism seems to have been changed by this genre of publication.

Each director gets a book, maybe several

Start with auteurist criticism itself, as practiced in France and Anglophone countries. Let’s distinguish dossiers from critical appreciations.

A dossier collects documents about the director, while a critical monograph offers an ongoing argument. A dossier can spark ideas and introduce you to new information; a critical book focuses on a line of inquiry and marshals evidence around that. A through-composed book is a multi-course meal, while a dossier is a buffet, and sometimes a meal made of appetizers.

D. W. Griffith: American Film Master, a catalogue of an influential Museum of Modern Art exhibition of 1940, brought together a critical essay by Iris Barry, an interview with Billy Bitzer, and a filmography with commentary by Eileen Bowser. I can’t exaggerate the importance of such dossiers through the decades. Before the internet, these were precious sources of information for cinephiles and academics.

Critical studies of directors, as distinct from biographies and PR flackery, go back fairly far. While biographies like Roy Fuller’s little 1946 book on Orson Welles sometimes included critical discussions, the earliest pure case that occurs to me is Parker Tyler’s Chaplin: Last of the Clowns (1948), a very idiosyncratic reading of Chaplin’s films. André Bazin’s brief, powerful study of Welles appeared in 1950.

With Cahiers du cinéma and Positif celebrating the director as auteur, several publishers accepted the idea of a director-based book series. The first came from Editions Universitaires in Paris, and it was launched by Jean Mitry’s 1954 monograph on Ford. The books that followed were through-composed critical studies.

Three other French publishers provided more mixed models. The Seghers “Cinéma d’Aujourd’hui” series of squat, square paperbacks in stiff cardboard covers was a vast accomplishment, starting with Georges Sadoul’s 1961 book on Méliès. In a Seghers book, a critic’s long essay was followed by extracts from the filmmaker’s writings, snippets of reviews and critical commentary, and a fairly detailed filmography and bibliography. Because a substantial essay anchored a Seghers installment, it had some of the focus of a through-written critique.

“Premier Plan,” another series, came from Lyon, under the auspices of SERDOC (Société d’Études, de Rechereches, et de Documentation Cinématographique). Premier Plan books were usually flimsier than the Seghers ones. Some were simply filmographies with clip-quotes from reviews, but some, like the plump volume on Renoir, provided a substantial compilation of rare documents. Other entries featured long-form texts by experts like Barthélémy Amengual.

Yet a third series came into existence about the same time. The small-format entries in Anthologie du cinéma were published by L’Avant-scène, a company issuing texts of plays on a bimonthly basis. In 1961 it began publishing film scripts and transcripts as well. The first mini-monograph, Luda and Jean Schnitzler’s 1965 study of Dovzhenko, led to a great many dossiers, some on quite obscure figures.

All three series attracted some of the best critics and researchers. The old guard–Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, René Jeanne, Charles Ford–were balanced by the likes of Noël Burch, who wrote a provocative Seghers volume on Marcel L’Herbier, and Francis Lacassin, who contributed titles to both Seghers and Anthologie du cinéma. The 60s and early 70s were the boom years, when cinéphiles like me haunted the Gotham Book Mart, the Larry Edmunds Bookshop, and other specialty niches looking for that rare item on Anthony Mann or Vittorio Cottafavi.

In England, a new generation of critics caught the auteur wave. Peter Cowie modeled his International Film Guide series on the Seghers format, launching it with his monograph Antonioni–Bergman–Resnais in 1963 and following it up with his book on Welles and Robin Wood’s trailblazing Hitchcock’s Films (both 1965). Published by the Tantivy Press and distributed by the distinguished art-book publisher Zwemmer, these were in-depth critical studies. Cowie’s series was pluralistic, focusing not only on directors but on genres and periods. Eventually the series would run to dozens of titles, along with the indispensable International Film Guide, an annual begun in 1963, and a journal, Focus on Film (1970-1977).

A parallel enterprise was launched by the critics around the important British auteur journal Movie (1962-). Its bold pictorial design, the creation of Ian Cameron, carried over to “Movie Paperbacks,” which launched in 1966. The books published major monographs by Robin Wood, Charles Barr, Raymond Durgnat, Michael Walker, and Cameron and his wife Elisabeth. Many were single-authored, but there were as well important anthologies on Godard and others.

Cinema One, published by Secker and Warburg, was linked to the British Film Institute’s magazine Sight and Sound. Beginning in 1967 with Richard Roud’s book on Godard, that series followed the model of the Movie paperbacks in integrating stills and texts. Cinema One books were either through-composed monographs, like Geoffrey Nowell-Smith’s entry on Visconti (1967), or interview books like the vastly influential Sirk on Sirk (1972).

Probably the highest-impact entry of the Cinema World series wasn’t a director study. Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meaning in the Cinema (1969) introduced a generation to semiology. Such was the sway of auteurism, though, that in one chapter Wollen tried to revamp that critical approach with a structuralist analysis comparing binary themes in John Ford and Howard Hawks.

The 1960s saw an outpouring of auteur studies, along with many other books on film subjects. Because of the much bigger US market, the English series found copublishers and distributors stateside: Tantivy worked with A. S. Barnes, Movie with the University of California Press, and Cinema One with various commercial houses. Needless to say, the possibility of buying these books in local bookstores added joy to my college years. I remember getting Wood’s book on Hawks in Albany in 1968 and reading it immediately. Having already read his book on Hitchcock, I thought, Now we’re getting somewhere.

The 1960s saw an outpouring of auteur studies, along with many other books on film subjects. Because of the much bigger US market, the English series found copublishers and distributors stateside: Tantivy worked with A. S. Barnes, Movie with the University of California Press, and Cinema One with various commercial houses. Needless to say, the possibility of buying these books in local bookstores added joy to my college years. I remember getting Wood’s book on Hawks in Albany in 1968 and reading it immediately. Having already read his book on Hitchcock, I thought, Now we’re getting somewhere.

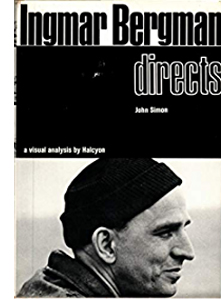

The illustrations in these books tended to be production stills, photos taken on the set during filming. Frame enlargements from the finished film were difficult to obtain, and their quality was questionable. But one American publisher incorporated actual shots from the movie. Under the mysterious imprint “a visual analysis by Halcyon,” Harcourt Brace Jovanovich produced Alexander Walker’s Stanley Kubrick Directs (1971) and John Simon’s Ingmar Bergman Directs (1972) with specific frames enhancing the critics’ interpretations. The quality of the images wasn’t always good (sometimes subtitles were left in), and one can imagine editors pointing to the results as proof that production stills were preferable.

These Halcyon books seem to have had little impact on other publishers, but both showed that heavily illustrated in-depth commentary on an auteur’s work was feasible for a book-length study. Simon’s close reading of Persona remains a remarkable accomplishment, as fine-grained a piece of interpretation as we can find anywhere at the time.

M. Hulot, boxed

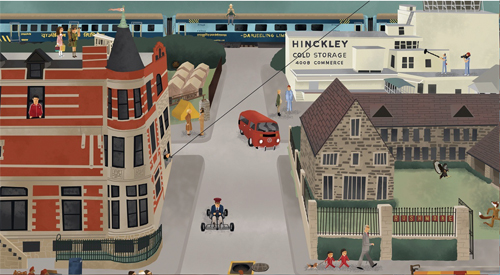

Mon Oncle (1958).

None of these books boasted big production values. The only de luxe auteur book of this period I can recall, and probably the prototoype of our Massive projects, was Donald Richie’s gorgeous The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1965). Published by the University of California Press but printed in Japan, it boasted excellent paper stock and authoritative critical interpretation, with Richie drawing on his unique access to personal conversations with Kurosawa. He displayed far more attention to style than most critics of his day, devoting sections of every chapter to cutting and camerawork. Arguably, the handsome interview book Truffaut/Hitchcock (1966) also paved the way for the large-scale auteur study. A little later, in a more obsessive vein, there was Robert Benayoun’s handsome oversize tribute to le fou Jerry, Bonjour, M. Lewis! (1972).

From the 1970s on, more lavish auteur volumes began to appear. Since they were expensive to produce, they were often the result of institutional support, and they tended toward the dossier format.

As the festival circuit expanded, those events hosted retrospectives of periods, genres, national cinemas, and, inevitably, auteurs. So it wasn’t surprising that Venice produced a high-gloss 1980 volume on Mizoguchi, with critical essays, interviews, and a detailed filmography surveying the master’s works, including lost films. For decades thereafter festivals created collectible catalogues based on their screenings. Followers of Hong Kong film, for instance, are forever in the debt of that festival for its in-depth publications on major figures like King Hu.

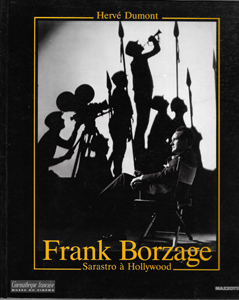

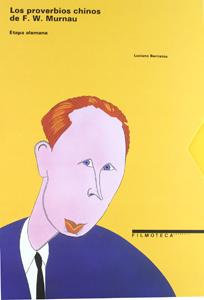

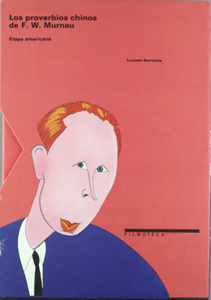

Similarly, just as museums published volumes commemorating major exhibitions, film archives began to finance catalogues derived from their programs. The books might be fairly modest, but some have been coffee-table quality. Usually these have been dossiers, but an important exception is Hervé Dumont’s monumental study Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (La Cinémathèque francaise, 1993). The most stupendous dossier-catalogue I know comes from the Filmoteca Espagnola and bears the curious title, Los proverios chinos de F. W. Murnau. Edited by Luciano Berriatúa, this two-volume boxed set (weight: ten pounds) is a feast for the Murnau admirer. Its glossy pages teem with original sketches and plans, frame enlargements, and ancillary information about the films and the director’s life. Its key image, in two color schemes, is also refreshingly unpretentious.

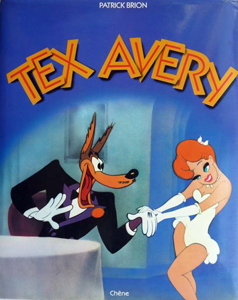

The French, as in other domains, have led the way with the deluxe auteur package. Patrick Brion, for instance, has written several large-scale studies. on animation and on directors like Joseph Mankiewicz (who’s much more deserving of a biopic than his brother, in my view). Cahiers‘ “au travail” albums, some translated into English, survey each director’s creative process by drawing on unpublished working documents.

From the 70s on, art-book publishers saw that there was a new audience among film fans and began to think of offering movie titles. There were quickie books, aimed for remainder markets and built out of publicity stills, but the prime player early on was Taschen, the firm long identified with distinctive books on the visual arts. Taschen, committed to producing books at all price ranges, released some inexpensive image-based movie titles, while also mounting unique limited editions of photography and painting. What else do you expect from a firm that offered as a bonus a stand to support a $25,000 book? (A baby version goes for just $1500.)

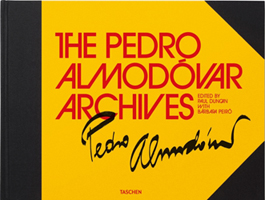

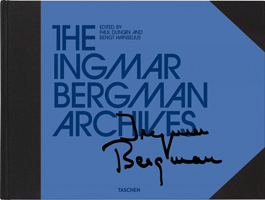

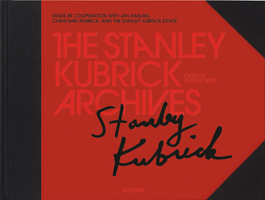

Taschen’s auteur campaign was part of its “Archives” series. Memorabilia and in-depth background from Star Wars, Disney cartoons, and the Bond films. were packed into huge horizontal-format volumes. In the same uniform design and binding came entries devoted to Almodóvar, Bergman, and Kubrick. It’s hard to know how to handle them for casual reading, but I suggest you supply your own table. The Kubrick volume was republished as a thick but more manageable volume; the paving stone became a brick.

But maybe the Archive releases aren’t really designed for normal reading. Like a gallery installation, they are easier to browse than to scrutinize. These books contain valuable primary documents, but a researcher into the subject would still yearn to see all those items that were kept back. One page of a script is interesting, but the scholar wants to see the whole thing. The Taschen volumes, impressive as they are, are high-grade fan compilations. They are stuffed yet tantalizing dossiers doing duty for an entire career: not so much an archive as an exhibition.

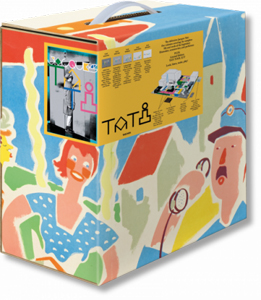

This year Taschen released an item that breaks with the design of the Archives line. The Definitive Jacques Tati, edited by Alison Castle, is is a five-volume boxed set. This homage to one of our most sprightly directors weighs nearly eighteen pounds, but the vaguely Bauhausian font and school-lunchbox packaging aim to lighten the tone. Volume 1, Tati Shoots, consists of production stills of scenes, each one given a separate page, as if it were a painting. Tati Writes offers scripts, reproduced complete (Jour de fête) or in extract pages, with English translations of the entire texts. Two unmade films, The Illusionist and Confusion, are included.

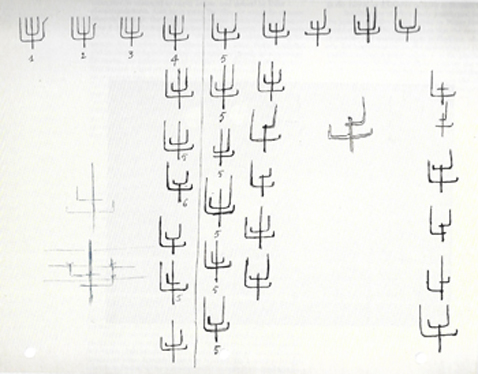

Tati claimed to have shot a film without looking at the script: “I know the film by heart.” The earliest screenplays in the volume are fairly minimal, but when we get to PlayTime, one of the most strenuously dense films of all time, the description of a single shot’s action can run to hundreds of words. The Royal Garden sequence, an hour-long tour de force, was planned in daunting detail, notating gestures, eye movements, and even the virtuoso matches on action.

The screenplay of this sequence is often packed with many more gags and bits of business than are onscreen in the versions we have. For instance, one of my favorite gags takes place when the air conditioning is switched on and we see the skin on a woman’s back ripple. Soon the fan is adjusted and her flesh settles down.

Apart from its sheer audacity (who thinks of a gag like this?), it comments on the flabby patronage of the restaurant. It also recalls the puffy plastic chairs that earlier bewilder Hulot by erasing his presence.

The AC gag is more elaborate in the screenplay; a technician fiddles with the controls, making the undulations vary until the adjustment is right. I don’t find an account of the provenance of the published PlayTime text , but if this is something like a late shooting script, Tati made enormous alterations, usually simplifications, during filming.

Volume 3, Tati Works consists of a biographical chronology and illustrated with family photos, followed by segments devoted to phases of his career, also heavily illustrated. It’s here that we get behind-the-scenes images of Tati at work. There are appreciative essays on the films, filling in background on the production and reception of the films while pointing up some of Tati’s artistic strategies. The writers acquaint readers with the core ideas of Tati criticism: comedy of observation, comments on modern life, deep and decentered composition, ricochet gags, anomalous sound effects. Most of these essays are by Jonathan Rosenbaum, who worked with Tati, while Jacques Kermabon and Alexandrine Dhainaut contribute background on the early films and the unfilmed projects respectively. Quotations from collaborators round out the volume.

Tati Explores consists of essays on recurring images (vehicles, architecture) and auditory strategies, by a range of French critics. These and the earlier essays are fairly brief and synoptic, in keeping with the general policy of favoring pictures over texts. Still, in volume 4 in particular, documents drawn from the archives often illuminate Tati’s creative process. We can see how the Mon Oncle gag with the spiny foliage was obsessively elaborated in advance.

All this personal material made me think that perhaps we should go beyond treating Tati as an isolated artist, as if the local or global film industry had no impact on him, or him on it. His international standing as both filmmaker and performer was made possible partly by his brilliance as a mime, partly by his charmingly eccentric persona, and partly by subjects and themes that were widely intelligible. It seems to me that his easily grasped satiric targets (old versus new, country versus city, people trapped in routine, overweening technology) enabled him to make formally and stylistically complex movies. He smuggled innovative narrative and style in on the back of clichéd material.

In other words: We can always ask new questions.

The final volume, Tati Speaks, includes more on-set images, along with quotations from interviews. Again, pictures dominate, but there are some longish interviews at the end that allow Tati and his questioners to develop real conversations.

In all, The Definitive Jacques Tati is a kind of ultimate dossier collection, an act of homage that also aims to be a precious object in its own right. You can, up to a point, fondle these bulky volumes. For more hands-on engagement, you can upgrade to a numbered limited edition that includes a miniature set you can assemble yourself. Price $895 until 31 January 2021, thereafter $1000.

Immersed in Wesworld

The whimsicality of the Tati box’s design, so different from the solemn slabs of Taschen’s Archive series, is in keeping with a new direction in the Massive Auteur Monograph. That tendency emerges most vigorously at another publisher, Abrams. Abrams had already embraced film animation as an art form, producing Helen McCarthy’s beautiful volume on Osamu Tezuka.

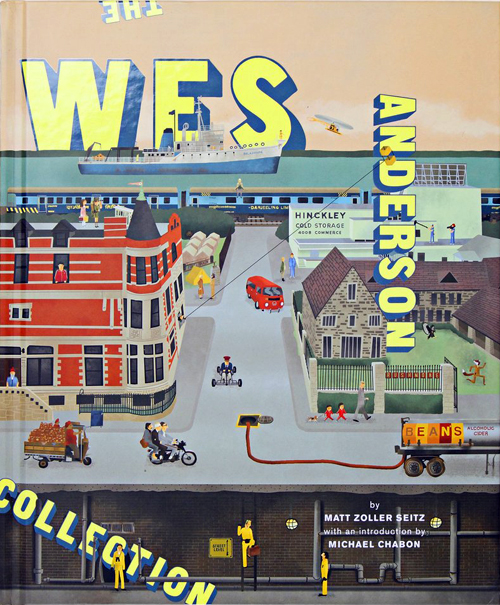

The new auteur bent is especially evident with Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Wes Anderson Collection (2013). It looks like a dossier, but actually I’d argue it’s an unusual critical monograph. Organized chronologically, film by film, it’s called by Seitz “a book-length conversation interspersed with critical essays, photos, and artwork.” As with the Taschen Archives, Seitz’s access to the filmmaker allows him to include working notes and sketches, storyboards and tests.

Ins tead of a linear argument, Seitz offers a collage on interwoven themes in and around Anderson’s work, particularly his appetite for both high and low culture. Seitz’s free-range imagination comes up with influences and sources not obvious to an outsider. Who else picked up on Anderson’s debt to Peanuts and Star Wars? And Seitz can discuss these possibilities with the director. The sense of a running dialogue spills over every page, where the captions continue to make connections and send you flipping to other pages. These are a fan’s notes on a Borgesian scale, the print equivalent of hyperlinks.

tead of a linear argument, Seitz offers a collage on interwoven themes in and around Anderson’s work, particularly his appetite for both high and low culture. Seitz’s free-range imagination comes up with influences and sources not obvious to an outsider. Who else picked up on Anderson’s debt to Peanuts and Star Wars? And Seitz can discuss these possibilities with the director. The sense of a running dialogue spills over every page, where the captions continue to make connections and send you flipping to other pages. These are a fan’s notes on a Borgesian scale, the print equivalent of hyperlinks.

The biggest breakthrough comes, I think, with a design decision. Instead of through-composing a critical argument, weaving interview quotes and claims about influences into seamless prose, Seitz decided to soak the whole package in Anderson-ness. The slightly tense nerdery, the OCD fixation on lists and details, the deadpan naïveté of the films–all are replicated in the very texture of the book.

Anderson’s vision, which creates childhood worlds filled with adult anxieties, is rendered in a sort of tween book for grownups. Each section is given an absurdly precise annotation (“”The 1,113-Word essay,” “The 7,065-Word Interview”). Each Anderson film invites us into a densely furnished milieu, and the book eagerly assists his near-maniacal worldbuilding. Bonus material includes logos and indicia from the fictional companies, organizations, and texts. Reproducing the yearbook montage from Rushmore, Seitz supplies “activity cards” drawn from shots from the film. A pastiche ad for The Dollar Book Club (in Garden City, of course) offers for a mere $1 the library books Suzy has swiped in Moonrise Kingdom.

Seitz’s artwork includes color drawings by Max Dalton that reinterpret the inhabitants of Wesworld as wispy cutouts, arms hanging down, as if in a police lineup or a paper-doll sheet. Often with their eyes lowered, they have the awkwardness of exceptionally intelligent people who haven’t yet figured out “self-presentation” and “impression management.” Under Dalton’s hand, a landscape becomes an urbane New Yorker rendering of Grandma Moses.

The real tipoff, I think, comes with the end papers, which consist of a vast grid of characters as imagined by Dalton. This is a book Anderson characters would like to own: geek chic.

Unsympathetic critics who find the films over-cute (I’m trying to avoid the label “twee”) will find this a double dose of it. I, who like the films, find it a fascinating step forward in rethinking what the auteur monograph could be. The sequels devoted to The Grand Budapest Hotel and Isle of Dogs embrace the dossier format, incorporating essays and interviews from others. But the presentational mold was set: each one is a piece of bespoke Andersoniana. Seitz went on to apply the same principle to a very different director, Oliver Stone, and he gave that Abrams book an appropriately tense, smashmouth aesthetic. Interviews are scoured by redactions, illustrations are psychedelic jumbles.

Auteurism on steroids

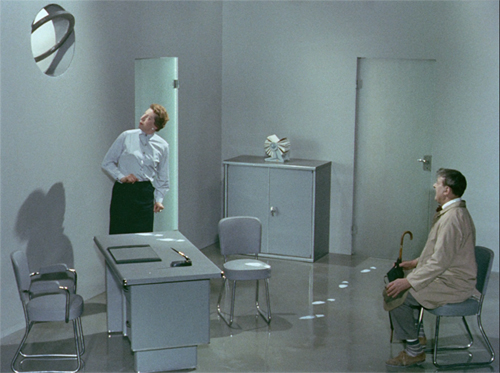

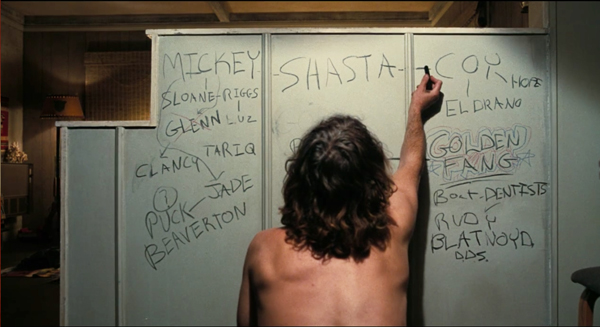

Inherent Vice (2014).

Most recently, Abrams has given us two Massive Auteur Monographs, written by Cinema Scope and Little White Lies critic Adam Nayman. Considering them alongside the Seitz books, we can spell out some conventions of the new model–some inherited from classic auteurism, some in the process of emerging.

*Deep-dyed Auteurism. The title The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together (2018) says it all. The director(s) has (have) a unified but nuanced vision, the critic will reveal it, and aficionados will understand the subtitle as both an homage and a meta-reflection on auteurism itself. The Coens have a “comic universe” of rich interconnections. In the same vein, Nayman’s Paul Thomas Anderson Masterworks (2020) cautiously acknowledges Anderson as bearer of “a heroic–indeed, mythic auteurism, bridging past and present, personal and populist.” In an age of blockbusters, “ambitious, challenging American films” will always demand “auteurist approbation.” The critic can uncover the inputs of collaborators and draw out their ideas in interviews, but the director remains at the center: at least a synthesizer, and at most a demiurge transforming everything into something personal.

*Deep-dyed Auteurism. The title The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together (2018) says it all. The director(s) has (have) a unified but nuanced vision, the critic will reveal it, and aficionados will understand the subtitle as both an homage and a meta-reflection on auteurism itself. The Coens have a “comic universe” of rich interconnections. In the same vein, Nayman’s Paul Thomas Anderson Masterworks (2020) cautiously acknowledges Anderson as bearer of “a heroic–indeed, mythic auteurism, bridging past and present, personal and populist.” In an age of blockbusters, “ambitious, challenging American films” will always demand “auteurist approbation.” The critic can uncover the inputs of collaborators and draw out their ideas in interviews, but the director remains at the center: at least a synthesizer, and at most a demiurge transforming everything into something personal.

*A Criticism of enthusiasm. It was a tenet of Cahiers du cinéma that the best reviewer of a film was the critic who most liked it. To critics of a judicial bent, that looked like defection from the role of stern magistrate, but the idea was that the best possible case for a film would be made by an admirer. Nayman is unabashed. Phantom Thread is “a surpassingly funny movie,” Raising Arizona is “fully endearing,” Magnolia is “something to behold.” Enthusiasm doesn’t equal blind worship. Nayman doesn’t find the films flawless. He also grants his changing estimation of Anderson’s career as it developed. Still, these are judgments made within a broader attitude of passionate support.

Arguably, shortcomings are minimized by a Massive book’s sheer footprint. Enthusiasm can come through in a short piece or a small, square book, but The Coen Brothers and Paul Thomas Anderson Masterworks fill about 300 large-format pages apiece and weigh between three and four pounds. Size matters. When packed into the howitzer dimensions of a coffee-table book, the case for the value of the director is strengthened by sheer avoirdupois.

*Personality plus. Andrew Sarris posited “the distinguishable personality of the director” as a central criterion of value for the auteur critic. He didn’t distinguish between the personality of the actual flesh-and-blood filmmaker and the “personality” projected in the work. Modern critics are more careful, but there’s still an impulse to study the works in light of everything we can know about the artist’s life, influences, and obsessions. Hence critics’ continual pursuit of how the private lives of Hitchcock, Welles, and other directors inform their work.

The concentration on the director’s personality led many skeptics to consider auteur criticism as a throwback to Romantic aesthetics, where the all-powerful poet infuses deep feelings and formative experiences into the art work. Part of Wollen’s heresy in Signs and Meaning was to sever the films from the living creators.

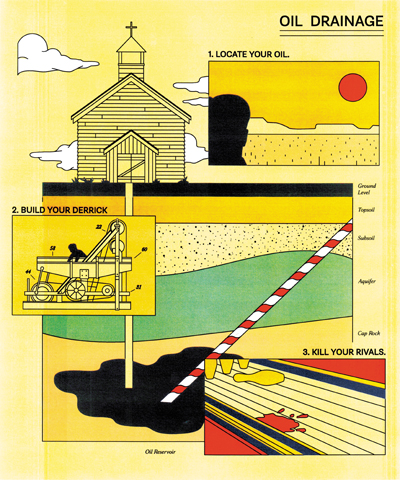

Like Seitz, and indeed like most auteurists since the 1960s, Nayman is sensitive to the director’s transformation of prior material. He will study how an adaptation reweights the original, as when There Will Be Blood trims political contexts from Sinclair’s Oil! More important, he will probe the more tenuous inspirations working under the surface of the finished film. We can’t recover many of those subterranean currents from the days of Hawks or Mizoguchi, but focusing on living filmmakers gives these monographs an advantage. Authors can question the director (Seitz) or track down interviews (Nayman) that bring out a hidden network of intimate inspirations. Seitz discloses Rushmore’s debt to Peanuts, and Nayman links Inherent Vice to the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers–and Leonardo’s Last Supper.

The personality factor gets magnified in the age of the Massive Auteur Monograph. The scale of the enterprise lifts the film director to the level of a gallery artist, putting idiosyncrasy on display. Moreover, whereas old-style auteurists could signal debts to Pirandello or Picasso by passing references in prose, the big-ass Auteur book can spread out a bounty of iconography: paintings, snapshots, album covers, comics, and virtually anything else. For the Coens we get a cartoon illustration of books that influenced them; for Anderson, there’s an interpolated series, “PTA’s Movie Collection.” This almost philological archaeology is part of the Massive project’s raison d’être.

*Something to say. When I told a friend that I thought Spielberg was an exceptionally skilful filmmaker, she agreed but added: “Too bad he has nothing to say.” An auteur is held to be an artist, not just an artisan, and an artist gives us something meaningful in and through the artwork. Guided by this premise, auteur criticism has traditionally been focused on thematic interpretation. How does the filmmaker’s personal angle of vision transform the thematic material?

Nayman acknowledges that critics have found a nest of themes typical of his subjects: male inadequacy in the Coens, father/son relationships in Anderson, and more. He develops these and others in his own interpretive commentary, and like Seitz, he has incorporated frame enlargements into his argument, so his claims gain specificity. Shots from Punch-Drunk Love counterpose a map and the abandoned harmonium as evidence for “the desire to travel” set aganst “a symbol of potential order that must be protected and mastered for the character to achieve self-actualization.”

The Massive format allows critical commentary some new opportunities. Interpretive asides can be attached to sidebars or even the stills parked along the main text. Whereas your classic picture book has a neutral caption, the captions in the Abrams books tend to make critical points by hooking the picture to the text or other illustrations. In addition, the urge to fill out the format allows the critic to expand the interpretation through bonus materials. The tabletop landscapes of Wesworld created by Dalton find their counterparts in Nayman’s books in original illustrations that offer artists’ interpretations of the story worlds. In this illustration for There Will Be Blood, George Wylesol provides glimpses of motifs recognizable only if you’ve seen the film.

The movie opens up. Classic auteurism tended toward traditional notions of “variety in unity.” Robin Wood’s Hawks monograph, for instance, is a rigorous argument for a few recurring themes and variations in the director’s most characteristic work. But the sheer expanse of a Massive project–swallowing up all the films, even ephemera like shorts and uncompleted projects–and the search for the most remote and tenous links to books, cultural events, other films, and almost anything else, work against a more austere delineation of the artist’s achievement.

The risk is that the critic’s argument is overshadowed by the bonus materials, the way the vast making-of supplements to The Lord of the Rings DVDs vie for attention with the movie itself. At best, though, the ancillaries pry the film open. The books are large, they contain multitudes, and so do the films. Like a webpage bristling with links and pop-ups, the books invite you to see the films stretching tentacles out in all directions.

*Criticism as creation. However humbly the auteurist approaches the director, criticism remains partly a performance. If the filmmakers stand out as personalities, so too does a critic. Seitz, for instance, emerges from his books as a voracious, encyclopedically knowledgeable pop-culture maven. Nayman strikes a more academic tone, invoking in one page Freud’s oceanic feeling, the idea of structuring absence, and signifiers. Again, from the sixties auteur criticism always straddled belletristic writing (call it haute journalism) and academic studies. (Scads of university press books have taken the auteur line.) Nayman, like many ambitious critics, draws on academic ideas pointillistically, subordinating them to the tasks of appreciation.

But we’d be selling these books short if we didn’t acknowledge their efforts to treat criticism as a striking creative act in its own right. Nayman revises some norms, as when he foregoes film-by-film chronology in the Anderson volume. More radically, from the full-page cartoons and original illustrations to the bespoke endpapers and the marginal curlicues (tumbleweeds in The Coens, doodles in Anderson Masterworks), the books aim to become supplements to the artist’s achievement. No surface is spared from Auteurist High Concept, as when the back cover of The Coens invokes not only The Big Lebowski but Nayman’s argument that the films play out circular patterns.

But we’d be selling these books short if we didn’t acknowledge their efforts to treat criticism as a striking creative act in its own right. Nayman revises some norms, as when he foregoes film-by-film chronology in the Anderson volume. More radically, from the full-page cartoons and original illustrations to the bespoke endpapers and the marginal curlicues (tumbleweeds in The Coens, doodles in Anderson Masterworks), the books aim to become supplements to the artist’s achievement. No surface is spared from Auteurist High Concept, as when the back cover of The Coens invokes not only The Big Lebowski but Nayman’s argument that the films play out circular patterns.

Through-composed to the max, each book proposes itself as an art object that, though coming after the fact, has as valid a tie to the oeuvre as the innumerable works that influenced the makers. One venerable publishing tradition, to which both Taschen and Abrams belong, is committed to creating artworks about artworks.

Auteurism can be fun. All this intertextuality might have been solemn in the manner of literary criticism, but it turns out to be almost giddily playful. Tati, the Coens, and Wes Anderson invite a light touch, and more serious auteurs like Stone and Paul Thomas Anderson have their wild sides that can be celebrated in unpretentious new illustrations. With their echoes of books you flopped on the floor and read on your tummy, these publications offer a surprise every time you turn the page. This appeal to the kid in us, always bracketed by our knowledge that we’re deliberately indulging ourselves, gives auteurism something that millennials might latch onto. It carries a bit of that hip knowingness that Thomas Frank in The Conquest of Cool has described as the dominant way many of us consume popular culture.

That knowingness, steeped in authentic love, is central to fandom. Auteurists have always had a fannish streak. If we are all nerds now, then we can see the Massive Auteur Monograph’s emergence as owing something to what’s been called the “fan-favorite” publishing genre. The parallel is obvious: Wes Anderson fans aren’t as numerous as Star Wars fans, but they’re no less devout. (Some proof is here.) With suitable adjustments, the production values of books like The Transformers Vault (2010) could be transferred to The Wes Anderson Collection. Abrams Executive Editor Eric Klopfer explains that some filmmakers, themselves fans, are receptive to such projects. “These types of books are very close to their heart,” Klopfer says. “Many of them were influenced by these books as they were coming up.”

Books like Seitz’s and Nayman’s may make old-guard cinephiles rethink what film criticism can be, and they may introduce young people to auteurism itself. If these books came out when I was fifteen, I’d probably think they were the coolest things I’d ever seen.

Absorbing the lessons of the MAM

Inception (2010).

In various ways, then, these books are redefining critical writing. We should expect more Massive Auteur Monographs; the next Wes Anderson one has already been announced. But we can see their influence in less obvious ways, and I think Tom Shone’s new book on Christopher Nolan suggests some other intriguing options.

Shone has written one of the best books on post-1970s Hollywood (Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer, 2004), and a Massive Auteur Monograph (Tarantino: A Retrospective, 2017). His newest project, The Nolan Variations: The Movies, Mysteries, and Marvels of Christopher Nolan, seems at first glance a more traditional effort. Although it’s heavy-duty (2.6 pounds), it doesn’t need a big form factor. In Nolan’s case, the mission of fan pageantry has already been accomplished by James Mottram’s informative and picture-plentiful behind-the-scenes books, authorized by the director.

Shone has written one of the best books on post-1970s Hollywood (Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer, 2004), and a Massive Auteur Monograph (Tarantino: A Retrospective, 2017). His newest project, The Nolan Variations: The Movies, Mysteries, and Marvels of Christopher Nolan, seems at first glance a more traditional effort. Although it’s heavy-duty (2.6 pounds), it doesn’t need a big form factor. In Nolan’s case, the mission of fan pageantry has already been accomplished by James Mottram’s informative and picture-plentiful behind-the-scenes books, authorized by the director.

Shone subscribes to most of the auteur conventions I’ve mentioned, although he’s somewhat more straightforwardly critical of certain films or moments. On the whole, this is a work of auteurist advocacy. Shone presents Nolan as both a craftsman interested in technical problems and a visionary director with a unique perspective on themes of time, identity, and history.

Shone moves chronologically from film to film by means of old-fashioned literary prose. He examines plot, character, visual style, and, in gratifying detail, music. He gives up the choppiness of the dossiers and the centrifugal pressures of the Abrams model. There are no sidebars and little effort to identify the physical book as an extension of the films. Frame enlargements, along with extrinsic visual evidence like storyboards and posters for influential films, are subordinate to the ongoing argument. So are the captions, which aren’t as chatty as we tend to get in the Abrams books. This is a book demanding one-track reading.

Yet it doesn’t sacrifice the intimacy and detail of the Massive ones. Part of its originality lies in the effort to enhance the idea of authorial personality through traditional biographical criticism. Shone suggests that Nolan’s concern with pattern has roots in his youth, particularly his years growing up in a highly regimented boarding school. Shone also provides an intellectual history of Nolan’s philosophical concerns. Kant shows up in the fifth paragraph, and soon enough we encounter Helmholtz and Penrose–names you don’t expect to meet in books about the Coens.

This isn’t showboating. Shone argues that these thinkers shaped Nolan’s art as decisively as did Chariots of Fire and Pulp Fiction. Nolan’s artistry draws from high culture as well as middlebrow and popular sources. Shone traces how philosophical ideas surface in the form and style of the films, from the play with time to Nolan’s concern with the Shepard tone as a model for both music and narrative organization.

Apart from tracing how the films are shaped by Nolan’s reading and thinking, Shone absorbs another level of discourse into his account. He met Nolan on several occasions after 1999. Instead of separating out chunks of their conversation as inserted interviews à la Seitz, he weaves their ongoing discussions into his film-by-film discussion. This gives the book an almost novelistic structure, which traces as a subtheme the progress of the two men’s dialogue.

Early on, Shone does detective work on Nolan’s personal history and proposes some interpretations that Nolan hesitates to grant. (“I was always very resistant to the notion of biography as it applies to criticism.”) Their encounters engender a degree of novelistic suspense when early on Nolan proposes a challenge: In words only, over the telephone, explain the concept of left and right.

Shone’s efforts to solve the problem become a running motif and inject a sting of drama into the book’s final pages. The problem and a couple of solutions are left wobbling at the end, like the top in Inception. No need for a still and a caption: Shone has woven the films’ imagery and structure, his investigation of them, and his conversations with Nolan into such a tight fabric that the reader gets the point. The project becomes, in its final lines, as cryptically reflexive as Nolan’s own work.

Perhaps Shone would have thickened the traditional auteur study in these ways without the existence of the more extroverted Monographs. But I can’t help thinking that The Nolan Variations (itself a reflexive title, with the critic as keyboard performer) has quietly absorbed the lessons of the more flamboyantly virtuoso projects. If they’re like Ives symphonies, this is more Mahlerian. The breaks and discordances are less evident, but the range of ambition remains.

The Tati box aside, these books are generously priced. In an era when a forgettable novel costs about twenty bucks, these books are offered at $40 or less. (The tiny Movie monograph I bought for $1.95 in 1967 would cost over $23 in today’s currency.) And Taschen’s compact Kubrick edition, at $20, reasserts the firm’s willingness to reach a wide audience.

Even if these books weren’t bargains, I think we need to consider them an important development in film culture. Just as the 1960s critical studies responded to the New Waves and Young Cinemas of that period, with their cult of the director, we can see the Massive Auteur Monograph as reacting to a host of cultural forces. There’s the ongoing idea of the celebrity director. There’s the wide availability of classic films to be referenced by both filmmakers and writers. Now we have the ability to scrutinize films on video. There’s the constant demands that modern publishing discover niche audiences. More and more, distributors promote the prestige of the Creatives. And of course the Internet has accustomed people to treating reading as multitasking. The dispersed layout of some of these book pages is like a monitor with many screens open.

Directors like Wes Anderson, the Coens, Nolan, and Paul Thomas Anderson are recasting auteur cinema for our time–not least in their willingness to cooperate on Massive Monographs. And books like these, whether presented as a bristling montage (Seitz, Nayman) or as a spiral tethered to core concerns (Shone), seem to me to revise auteurist criticism from the inside. Which only reasserts the study of directors as an enduring critical perspective.

I should disclose that I’m friends with Matt Zoller Seitz, and I’ve contributed to his volumes on The Grand Budapest Hotel and The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun.. I’ve become acquainted with Adam Nayman, Eric Klopfer, and Tom Shone through friendly email correspondence. Thanks to Adam and Eric for assistance with illustrations, and to Peter Cowie for background on Tantivy.

The “fondling” point is made by David Roberts in “The Changing Face of Publishing,” in Martin Edwards, ed., Howdunit:A Masterclass in Crime Writing by Members of the Detection Club (Collins, 2020), 401. The quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from The Primal Screen: Essays on Film and Related Subjects (Simon & Schuster, 1973), 50. I discuss Sarris’s account of auteurism in “Cinecerity,” Poetics of Cinema, Chapter 8, and in this blog entry.

For a fan-inflected but still carefully researched example of the Massive Monograph that’s devoted to a single film, see Jason Bailey, Pulp Fiction: The Complete Story of Quentin Tarantino’s Masterpiece (Voyageur, 2013). Interestingly, it came out the same year as Seitz’s first Wes Anderson book.

On Tati, for examples of in-depth analyses I’d recommend Malcolm Turvey’s monograph on Tati and comic modernism, or go back to Kristin’s pathbreaking studies of the 1970s and 1980s, reprinted in her Breaking the Glass Armor collection. We have considered Wes Anderson’s films in many blog entries. On Nolan our ideas are presented on this site and in revised form in our book on the director. I discuss some Coen directorial strategies in relation to a scene in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. On Anderson’s Magnolia as a network narrative, you can check Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema.

My 1981 book on Carl Dreyer, which I modeled on Richie’s Kurosawa study, might seem to be a step toward the Massive Auteur Monograph. My 1988 Ozu book might also count. But these are more academic and less freewheeling than the recent developments I’ve considered.

Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema proposes an account of thematic criticism as a practice. A recent blog entry on the subject takes The Hunt as an example. If you want to dig deeper, go here.

P.S. Ever-alert reader and high-energy critic Adrian Martin has signaled to me a large-format series I didn’t know about. The Théâtres au cinéma books were published by the now-suspended festival of Bobigny, France. The series is another example of institutional investment in a festival permitting de luxe publishing. Adrian writes that the choice of auteurs includes

Bellocchio, Ruiz, Fassbinder, Jarman, Robert Kramer, Akerman, Parajanov, Rocha, etc. And they are part of a mixed “arts festival event,” nominally a “cinema/theatre” crossover, that combines film retrospectives, theatre and music events, art exhibitions, readings of unproduced screenplays, concerts, etc. . . . There is often remarkable archival work involved: Kramer’s hand-assembled collages, previously unpublished texts by directors, interviewers with collaborators never before sought out by researchers (including, for example, Bellocchio’s psychoanalyst and co-writer for a while!). Even the ‘snippets of criticism’ that fill out the vast filmographies are a great resource.

Adrian praises in particular editor Cyril Béghin for his careful research and the high quality of the critical material he included. Thanks to Adrian for the tip!

Phantom Thread (2017)