Little things

Friday | August 13, 2021 open printable version

open printable version

Equinox Flower (Ozu, 1958).

DB here:

Academic critics and fans share a passion for looking closely at the movies we admire. A lot of film critics enjoy spiraling out from the film to ponder Big Ideas, which is okay, I guess. But I confess I particularly enjoy digging in for trouvailles (great word), lucky discoveries that passed me by on earlier encounters.

Across my career, many of the directors I admire seem to have tucked in little things just for me (or you). They don’t necessarily carry meanings; they’re quietly decorative, subtly off-center to the narrative. Tati slipped peculiar items into the corners of the frame. Sturges offered gags that only people with his sense of humor will find funny. A successful crowdsourcing enterprise exposed Welles’ homages to early film. Above all, Ozu nudged me toward red teakettles and surprising details. Who else lines up the levels of beverages in a table setting, and then matches that plane to the edge of a fruit bowl?

If you care enough about my movie, the director seems to say, I’ll reward you with a trouvaille. Here are two I found recently.

Showing the stitches

Sometimes a trouvaille is a felicity of craft. The director quietly shows off his virtuosity to those in the know. While studying Pulp Fiction for a book I’m finishing, I noticed that Tarantino sets up the ending in a sidelong way.

You’ll remember that the opening shows Honey Bunny and Pumpkin discussing how a restaurant is one of the safest robbery targets. Abruptly they launch an assault on the diner. Then they drop out of the film for a couple of hours.

Very likely we’ve forgotten about them when Jules and Vincent settle down for breakfast in a diner. After discussing the virtues of pork products and the prospects for Jules’ future, Vincent rises to go to the toilet. As he pauses, it’s possible, but not easy, to discern the larcenous couple out of focus in their booth behind him. Given their peripheral status and the centrality of Travolta’s performance, I suspect that almost no one notices them on a first viewing.

Soon after Vincent has left, we’ll hear a repetition of the final bits of the couple’s conversation and we’ll see a replay of their leaping up to announce the robbery. Tarantino has rewarded the sharp-eyed viewer with a slight anticipation of the replay, and a hint at how his film will fold back on its opening sequence.

But this echo is matched by a “pre-echo” during the opening sequence. As Pumpkin and Honey Bunny plan their heist, a close view of her includes a bulky man in a t-shirt walking into the distance.

At this point, a first-time viewer hasn’t been introduced to Vincent, so the t-shirt guy is just part of the scenery. Only in retrospect do we realize that here Tarantino is anticipating, and overlapping, the portion of the robbery that we’ll see in the final moments of the film.

Here the critic/fan is invited to appreciate how carefully made the film is. It’s a quality we don’t sufficiently recognize in Tarantino: a delight in fine-grained formal niceties.

Easter Egg, avant la lettre

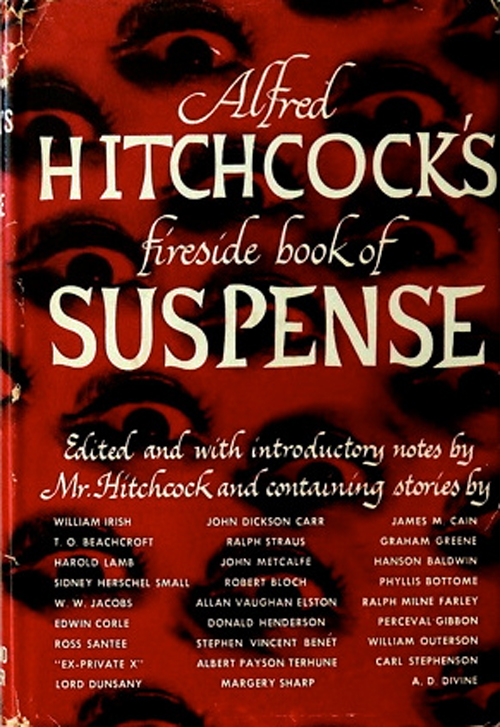

In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1950), tennis pro Guy Haines is introduced (implausibly) reading a book on his trip. Soon he’s accosted by the spoiled, marginally nuts Bruno Anthony, and the plot gets under way. Only a fan, or a critic, will want to know: What’s Guy reading?

It’s not easy to tell. We don’t get a close-up of the book. The best we can tell, from above, is that it’s a hardcover, with a photo on the back of the dust jacket. Later, after Guy and Bruno have shared a meal in a compartment, we can glimpse the spine.

Blown up, thanks to the glory of Blu-ray, the spine looks like this.

A little research reveals that the volume is Hitchcock’s collection of stories published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster.

Several anthologies were published under Hitchcock’s name from the 1940s onward, but most were in paperback. This was a more prestigious item, and I suspect it helped the branding effort that was underway during his Hollywood career. The picture on the back is of Hitchcock, of course. (My copy lacks a dust jacket, so I can’t supply that.) But the resonance comes from the fact that I was reading this very book as part of preparation for my own study of 1940s mystery culture.

It’s not exactly product placement; the book’s presence is too fleeting to register with audiences, surely. Including the book seems more in the nature of a private joke among Hitch and his team. Guy is a man of good taste, reading a book by the man directing the film he’s in.

Today we’re familiar with Easter Eggs, those bonus materials that establish a complicity between filmmmaker and viewer. Is this an early example? It could be a prize for fan connoisseurship. The book isn’t emphasized, being buried in the mise-en-scene, and so it encourages the devout to poke and probe. It also points outside the film to the production context. Still, how many 1950 viewers, lacking our ability to freeze and magnify the frame, could have spotted it? Perhaps only the devotion of a modern fan, aided by new technology, can bring this trouvaille to light. An incipient Easter Egg, then, awaiting digital technology to be discovered?

Once we’re down this rabbit hole, let’s scramble further. What stories might Guy be reading? There are two hints. We have the placement of the jacket flap in the shot above, and an earlier shot showing the book open.

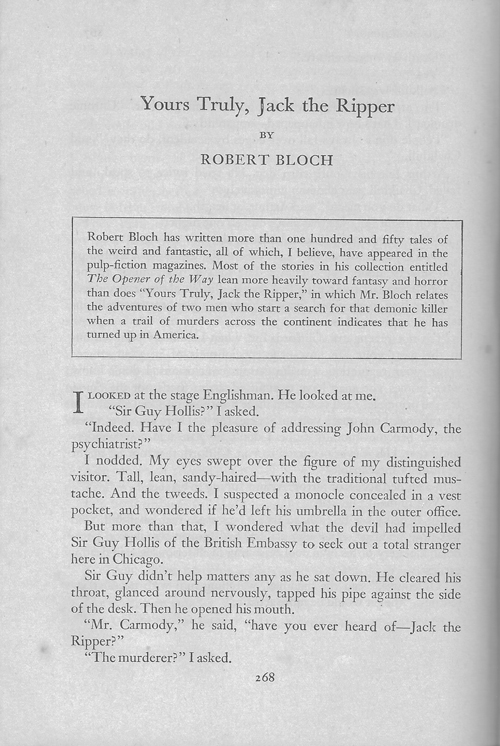

As best I can tell, the story Guy’s reading is likely to be “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” It tells of a psychiatrist who meets an Englishman called “Guy Hollis.” Sir Guy believes that Jack the Ripper has migrated to the US and is at large in Chicago. With the aid of the psychiatrist, Sir Guy finds him. Apart from the name Guy, the correspondence to Strangers it would seem to involve a peculiar bond between two men, one of whom is a psychopathic killer.

But there’s another, stranger affinity.

The author of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” is Robert Bloch., whose novel Psycho would furnish Sir Alfred his 1960 film. Coincidence? In the land of trouvailles, are there any coincidences?

Fans have raked over these movies assiduously, so I can’t imagine I’m the first to notice these fine touches. No matter. When you discover them on your own, you still feel a tiny thrill of communicating with the filmmaker, behind the backs of all those folks who didn’t notice. Ozu, I often feel, is making movies especially addressed to me. It’s an illusion, of course, but I refuse to give it up.

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin–Madison Filmies listserv for helping me understand what counts as Easter Eggs, and for a reality check on my sanity.

This site includes lots more on Hitchcock, Ozu, Sturges, and Tarantino. My book on Ozu is available from the University of Michigan. It takes time to download, so be patient.

P.S. 15 August 2021: As I thought, I’m not the first. A mere twenty-one years ago, Dana Polan in his monograph on Pulp Fiction (British Film Institute) noticed the pre-echo of Vincent headed toward the toilet. Good going, Dana! Film analysis wins again.

Days of Youth (Ozu, 1929).