Lau Kar-leung: The dragon still dances

Sunday | March 13, 2022 open printable version

open printable version

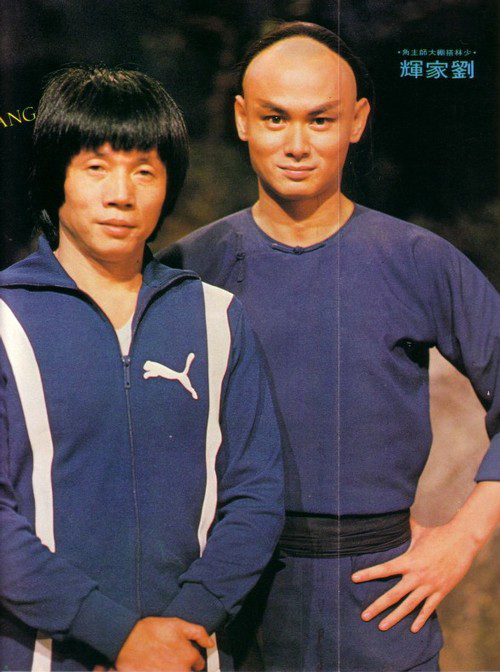

Lau Kar Leung (aka Liu Chia-liang, 1936-2013); Gordon Liu Chia-hui (aka Lau Kar-fei, 1955-).

DB here:

Back in 2020, I was asked to prepare a video lecture on the Hong Kong filmmaker Lau Kar-leung. Under the auspices of the Fresh Wave festival of young Hong Kong cinema, a retrospective and panel discussions were sponsored by Johnnie To Kei-fung and Shu Kei. The event took place in summer 2021. Tony Rayns also participated, offering a deeply informative talk that’s available here, but mine was not included. At a time when I hope people will continue to remember all that Hong Kong popular culture has given us, I’ve recast it as a blog entry.

For some years I’ve been arguing that the martial arts cinema of East Asia constitutes as distinctive a contribution to film artistry as did more widely recognized “schools and movements” of European cinema like Soviet Montage and Italian Neorealism. The action films from Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have revealed new resources of cinematic technique, and the filmmakers have influenced other national cinemas. The power of this tradition is particularly evident in Hong Kong cinema’s wuxia pian (films of martial chivalry), kung-fu films, and urban action thrillers from the 1960s into the 2000s.

Chinese martial arts are well-suited to the movie screen. The performance discipline, seen both in the martial arts and in theatrical traditions borrowing from them, yields a patterned movement that lends itself to choreography. The staccato quality of motion yields a pronounced pause/burst/pause rhythm that can be displayed and enhanced by film technique, as we’ll see.

These aspects of martial arts were captured by filmmakers working for the Shaw Brothers studios between 1965 and 1986. They cultivated a local style that yielded films that looked unlike any others. Thanks to the immense resources of the Shaw Movietown studio, complete with big sets and collections of costumes, the new filmmaking style was given a unique force. With The Temple of the Red Lotus (1965) and Come Drink with Me (1966), what Shaws called its “action era” began, and thanks to international distribution Shaws’ swordplay films gained audiences around the world.

Shaws’ Big 3

Shaw Movietown main office, 1997. Photo by DB.

The new trend benefited from Chinese opera traditions and the martial arts novels of Jin Yong, pen name of Louis Cha Leung-yung. They also owed a debt to Japanese swordplay films, many of which Shaws distributed and urged their directors to study. There was as well the influence of Italian Westerns. Just as important was Shaws’ investment in color and widescreen processes. Updating technology not only allowed the films to compete on the world market; it offered rich opportunities for artistic expression. (See the essay “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic adventures in Hong Kong.”)

Shaws directors quickly established conventions of the new swordplay film. Conflicts, of course, were expressed through combat, at least three major ones per film. One source of friction was the rivalry between martial arts schools run by masters; there might also be competition among traditions, regions (northern/southern), or nations (China vs. Japan). Typically there would be a hierarchy of villains, with our protagonists fighting them in turn. Plots would be more episodic than is typical in Western films. A looser structure favored including extensive set pieces of training or combat that were the appeal of the genre. And the plot would culminate in a long climactic fight, often to the death. These conventions, consolidated in the wuxia pian, carried over into the kung-fu films of the 1970s.

Two directors played central roles in shaping these conventions, and each had a distinctive approach to them. The vastly prolific Chang Cheh (Zhang Che) dominated the Shaws lot. He favored violent plots turning on revenge and intense male camaraderie, in which the martial arts served as a drama of loyalty or betrayal, friendship or deadly enmity. At the same period King Hu Chin-Chuan created one of the breakthrough “action era” works, Come Drink with Me, which immediately established a very different authorial vision. Hu was interested in historical and political intrigue, women warriors no less than male ones, and the martial arts as a spectacle of cinematic grace. Most of his major works, including A Touch of Zen (1971) were produced after he emigrated to Taiwan, although some were distributed by Shaw Brothers.

Neither Chang Cheh nor King Hu was trained in the martial arts, so they relied on choreographers to supply their action scenes. By contrast, Lau Kar-leung was a martial arts director who came to Shaws in the 1960s and choreographed many films for Chang and others. He took over directing duties in 1976 with The Spiritual Boxer and directed over twenty-five films for Shaws until 1985, when the company ceased producing theatrical features. He went on to direct several one-off projects until 2002.

Lau took the uniqueness of martial arts traditions more seriously than other directors, building entire films around one school or another, or among the contrast of rival traditions. He often opens the film with an abstract prologue showing off characteristic moves and tactics of the style that the film will treat. Unlike Chang, he is less concerned with male loyalty and violent revenge and is more inclined toward redemption and forgiveness. He shares Hu’s refined conception of film technique, but he is less overtly innovative. He refined stylistic conventions that were already in place at Shaws and many of which were basic to world cinema storytelling.

For example, Lau accepted the elevated production values demanded by the Shaw product. His films are filled with elaborate sets, both interiors and exteriors, and rich color values. He also recognized the power of editing, something that King Hu had brought to the fore. In the rest of this entry, I’ll concentrate on four of Lau’s distinctive innovations in the Shaws style.

Filling the wide frame

All widescreen filmmakers faced the problem of filling the spacious frame. (See CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses” for discussion of American solutions.) The big Shaws sets enabled filmmakers to pack the frame with figures and settings. We therefore find plenty of dense long-shot compositions.

We also find flashy closer views. Chang Cheh was particularly fond of low-angle medium shots, which he considered “warmer” than straight-on or high angles (The Assassin, 1967; choreographed by Lau).

Hong Kong directors relied on “segment shooting” for action scenes. Instead of overall coverage, with repetitions for different camera angles (the US norm), they plotted the fighting moves for specific camera angles and shot them separately. By calibrating the performers’ actions to the camera setup, they created a unique blend of martial arts techniques with film techniques. Rather than simply record martial-arts movements, filmmakers “cinematized” them.

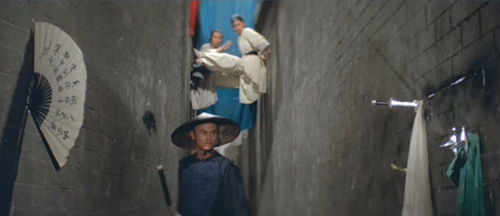

Lau seems to have taken particular pleasure in filling his frames in ingenious, fluid ways. He enjoyed the challenge of staging combat scenes in confined spaces, so that he couldn’t rely on expansive vistas. Partly, this tactic enabled him to show how different moves were required in close quarters. One of his favorite sequences was in Martial Club (1981). He explained:

Gordon Liu is fighting Johnny Wong in an alley that narrows from 7-foot to 2-foot wide. The physical limits of the alley actually make the best showcase for the different boxing schools. How do you fight in a seven-foot-wide alley? You use big arm and leg movements. Going down to five-foot wide, you keep your elbows close to your body because you don’t want to expose yourself. Further down to three-or-four foot wide, you use Iron String Fist. Finally when you get down to two-foot wide, you engage the “sheep trapping pose.” The results were sensational.

At the same time, the narrowing alley offered rich opportunities to fill the frame with body parts and abstract slices of walls.

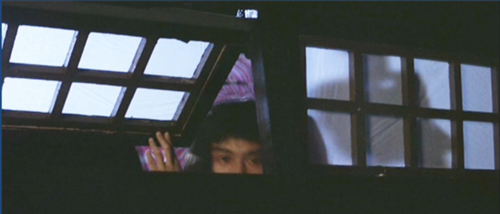

Something similar occurs in Legendary Weapons of China (1982), where two assassins must hide in an alley above a third. This time Lau uses some props to fill out the wall areas.

Lau delights in the possibilities of close fighting in any space. Sometimes the confinement isn’t a matter of setting; it’s dependent on letting the film frame itself constrain the action. Take a portion of a sequence from Dirty Ho (1979). The Prince (in disguise) calls on Mr. Fan, who tries to attack him, all the while pretending to play the host by offering wine.

Establishing shots lay out the zones of action to come, the chairs the men will occupy. Even a momentarily unbalanced framing is compensated for by movement in the empty area.

The first phase of the scene takes place in much closer framings, often tight two-shots. It’s here we see Lau’s virtuosity in finding constantly fresh ways to fill the frame, with compositions always picked for maximum clarity: that is, in showing Fan’s aggression and the Prince’s resourceful blocking, sometimes with comic symmetry.

The pause/burst/pause rhythm gets played out in low angles, with slight camera movements to adjust to the gestures.

The two major props, the fan and cups, get a real workout as they participate in the constant ballet of arms, faces, and fingers. All areas of the screen get activated: top, bottom, corners and sides.

Later in the scene, in a passage I haven’t included in the clip, the servant gets to take part, so now even more body parts are spread across the frame–and a cup even comes out at the viewer.

The scene ends with a comic commentary on the props: master and servant collapse at the table as a cup overturns.

This “close-up action scene” is as fully designed for the widescreen as any expansive long-shot sequence might be, but there’s a particular enjoyment to be had in seeing how a director can do so much with simple components.

Editing: Analytical cutting

Contrary to what many think, Chinese action pictures rely heavily on editing. At Shaws, King Hu pioneered extremely rapid cutting, reducing shots to half a second or less. Lau became a rapid cutter as well; his films from the 1970s and 1980s typically average three to five seconds per shot, with some films containing over 1000 shots.

It’s commonly said that Hong Kong martial arts films favored full shots and long takes, the better to respect the overall dynamic of the combat. Full shots, yes; but not necessarily long takes. While Western directors tended to believe that long shots had to be held quite a bit longer than closer ones, Hong Kong directors realized that long shots could be cut fast if they were carefully composed for quick uptake. Lau’s mastery of composition stands him in good stead when he starts putting shots together: every combat, even the fast-cut ones, are crystal-clear in their execution.

Directors across the world had settled on two major editing resources: analytical cutting and constructive cutting. The first type shows the overall spatial layout of a scene and then analyzes it into partial views. Our Dirty Ho sequence is an example. Constructive cutting deletes the establishing shot and relies on other cues to help the viewer build up the scene mentally. Hong Kong filmmakers made extensive use of both types, and as you’d expect Lau is a master of each.

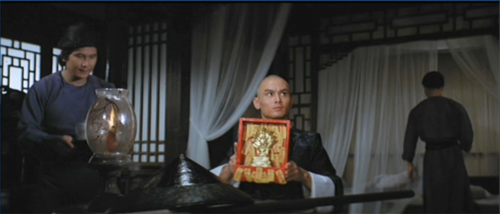

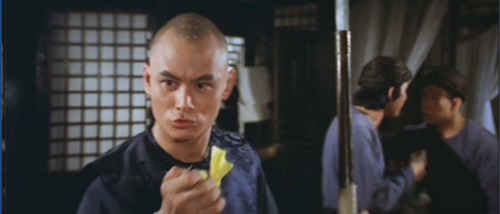

Most Hong Kong directors used analytical editing to favor the actors, to pick out their reactions to the ongoing action. Lau does this as well, as is seen in Dirty Ho. As you’d expect, Lau also uses cuts-in close views to emphasize combat tactics. In Challenge of the Masters (1976), after a villain (played by Lau) has felled his opponent, analytical cuts build to a revelation of a metal attachment to his shoe.

Executioners from Shaolin (1977) illustrates how Lau uses analytical editing during a large-scale fight scene. It’s far less constrained than the tabletop action of Dirty Ho, but he does find ways to narrow the action to particular zones. This is done through cuts to closer views–sometimes very close ones. And the editing is swift, with the average shot lasting only four seconds.

The scene’s opening establishes the hero Hung Hsi-kuan arriving at Pai Mei’s temple. There are two establishing shots, one a pan-and-zoom that presents the temple as Hung arrives, while the other (below) is a zoom back keeping the temple and Hung in the same frame. Both compositions stress the steep stairs leading up the hillside.

Once Hung starts up the stairs, more establishing shots reveal him surrounded. Lau indulges in a feast of different angles, stressing Hung’s vulnerability.

The scene’s second phase follows Hung’s progress up the steps. His encounters with many defenders are captured in a variety of angles, all of them orienting us to the changing situation. (At the top, he’ll encounter Lau himself, wielding a jointed staff.)

Camera setups on the steps themselves keep us aware of the forces arrayed around him. And the steps function a bit like the alleys in other films to limit the range of action.

The camera really penetrates the action, picking out details in the sort of tightly packed framings we saw in Dirty Ho.

Lau remarks: “You can get wonderful scenes of two pairs of hands folding and sliding in and out of each other’s grip.” This sort of tangible physical action is central to Lau’s scene analysis.

Analytical editing can include matches on action, cuts that let movement carry over across shots. Lau gives a virtuoso example in a match-on-action between extreme long-shots of a man in blue sent sprawling. The second shot ends with a zoom back.

It’s possible that Lau used two cameras for coverage of this, but that was a rare option in Hong Kong. It’s just as likely he managed the cut by repeating the fall, a movement stressed by a zoom back.

Again, you get a sense of a filmmaker challenging himself by setting up problems he will need to solve through mastery of his craft.

Editing: Constructive cutting

Trampolines and mattresses in shed on Shaw Movietown lot. Photo by DB.

The wuxia tradition features exponents of the “weightless leap,” the ability to spring very high into space. Before the advent of wirework and CGI, these soaring warriors were treated through editing that shows the leap in a series of shots. For instance, constructive cutting in Chang Cheh’s Golden Swallow (1968, choreographed by Lau) shows Silver Roc launching himself, soaring, and descending on his victim.

The jump was probably facilitated by a trampoline. On the screen, though, we see portions of the action that we assemble in our heads.

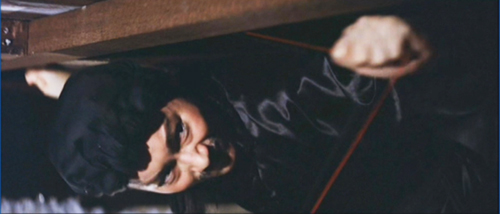

With his usual ingenuity, Lau sought out situations where he could test his skill with constructive editing–not just weightless leaps but combats among fighters at some distance from each other. My example is a brilliant sequence from Legendary Weapons of China (1982). (It takes place in semidarkness, so you may wish to adjust the brightness of your monitor.) Two rival assassins clash in a loft as they try to kill a third in the bedroom below. There ensues a three-way fight, pursued mostly through careful constructive editing.

There are a few establishing shots situating Ti Hau and Fan Shao Ching (disguised as a man) in the loft, but once they change their locations, most of the combat is given through constructive editing. That technique relies on cues of setting and character behavior (body position, facial expression, eyelines), and these are all mobilized early in the scene.

Details of props help us understand the action as well: the two threads bearing hooks and especially the gag with gas.

Once the assassin Ti Tan arrives on the floor below, pure constructive editing takes over. There’s no framing that includes him and his two attackers.

So Lau proceeds to cut together an ongoing fight upstairs (complete with fake meows) with Ti Tan’s suspicions downstairs.

The scene culminates in Fan and Ti Hau fleeing as Ti Tan, still suspicious, doubts that all the noise above him was created by a cat–and even the cat is presented through constructive editing.

In a sequence of 126 shots, the average is about two seconds, but each one is legible at a glance and carries the scene forward with utter smoothness. Lau’s precision in shot design serves him well when we have to assemble the action in our minds.

The smash zoom

Hong Kong action films of the 1960s are notorious for their use–some would say, over-use–of zoom shots. Yet at the time directors throughout the world were exploring the artistic possibilities of zooms. Most notable was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who coordinated the zoom with complex movements of actors and the camera. So we ought to consider the possibility that the zoom in Hong Kong was more than a technical gimmick to spice up action scenes.

For example, a smash zoom can accentuates the pause/burst/pause pattern of the fight. During one combat in Chang Cheh’s The Blood Brothers (choreographed by Lau), the zoom emphasizes sudden bursts of action by whipping back from a fighter.

Alternatively, the zoom can play up the pause by calling attention to moments of stasis. Here a cut emphasizes the pause as the fighters’s weapons are locked before the fight resumes with a zoom back.

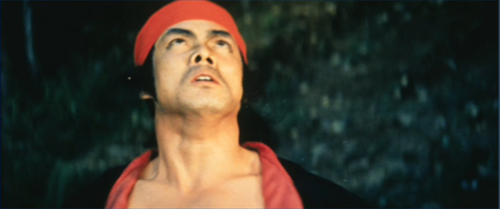

In such ways the zoom can break the fight into discrete stages. A far more elaborate instance takes place in Lau’s Return to the 36th Chamber (1980). Chu Jen-chi has painstakingly learned kung-fu at the temple through an apprenticeship of lashing bamboo poles together to make scaffolding. Accordingly, his technique is based on this very particular set of skills. I concentrate on the early stretches and the clip gives you some extra niceties. The whole thing is exhilarating to behold, thanks partly to energetic zooms.

Early on, the zoom introduces us to the lashing technique by showing the robe’s ripped fabric as a kind of handcuff.

Again we see Lau’s interest in watching how hands work, but here it becomes a specific combat tactic. The ensuing action will revolve around hands and wrists, and Lau’s zooms set up a question: What is Chu’s overall strategy?

The answer comes in a series of variations. First, Chu lashes his adversary to a bamboo pole like captured wild game.

Variation 2: Ensemble work. Chu takes on a batch of men, trussing them up horizontally.

He turns out to have in mind an engineering project, a sort of hitching post of miscreants. It’s capped by a shot of one of the Manchu bullies seeing his disciples’ wiggling fingers.

Variation 3: More ensemble work, now vertical, with the men’s wrists stacked like a bouquet.

Again, a master shot reveals the result and another close-up shows their wiggling fingers.

The kung-fu is of course extraordinary, but it takes an unusual cinematic imagination to heighten such elaborate patterns of movement in ways that are perfectly clear. Chu’s display of serious efficiency has a humorous side, capped by the gags that show the villains utterly flummoxed. We should ask if today’s action sequences in American films have this sort of unforced rigor and exuberance.

In the mid-1980s Shaw Brothers eased out of theatrical filmmaking, devoting Movietown to television production. Lau went on to one-off projects, some of which (e.g., Tiger on Beat, 1988) are well worth your attention. (Go here for the astonishing climax.) He had a late-career resurgence as choreographer for Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005). But his prime achievements, I think, will remain his vastly entertaining and filmically rich Shaws classics. His dedication to the specifics of martial arts lore, his unique sense of comedy, and not least his precise direction brought unique qualities to the remarkable tradition of Asian action cinema.

Chang’s remark about “warm” low angles is in Chang Cheh, A Memoir (Hong Kong Film Archive, 2004), 82; he discusses shooting The Assassin on p. 86. Lau’s comments on Martial Club come from “We Always Had Kung-Fu: Interview with Lau Kar-leung,” in Li Cheuk-to, A Tribute to Action Choreographers (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006), 62; the remarks on hands are on p. 59.

I discuss Lau further in both Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and in this blog entry.

Lau as the drunken master in Heroes of the East (1978).