Back in Bologna

Tuesday | July 7, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

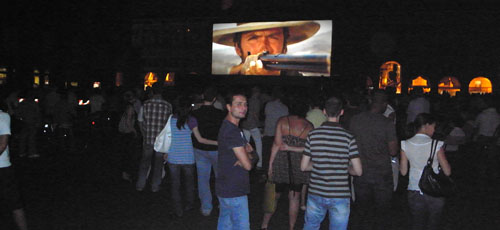

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

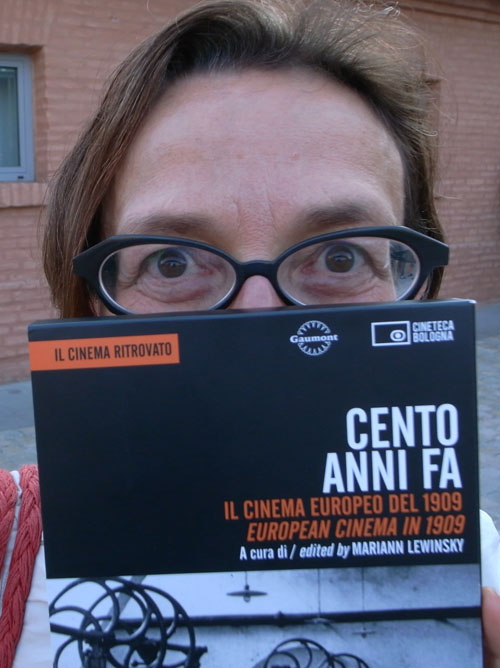

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.