Ellery who?

Sunday | December 18, 2022 open printable version

open printable version

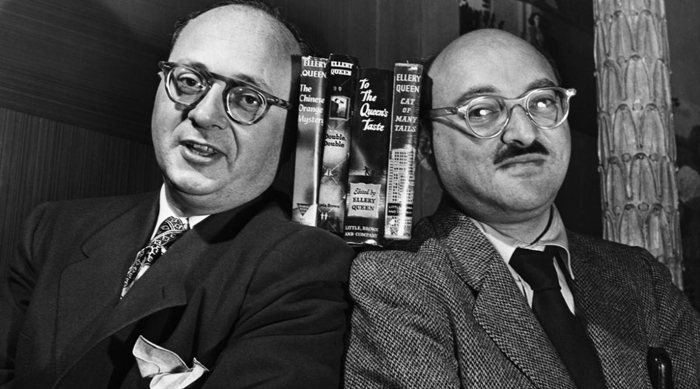

Manfred Lee and Frederic Dannay.

DB here:

My new book, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder, offers many critical discussions of classic mystery writers. But I couldn’t include every writer or work that interested me. So occasionally I’ll post blog entries that will fill in areas I skipped over. Some portions of the book analyzed work by Ellery Queen, but here I want to fill in some gaps–and remind contemporary readers of two writers who deserve more attention than they currently attract.

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

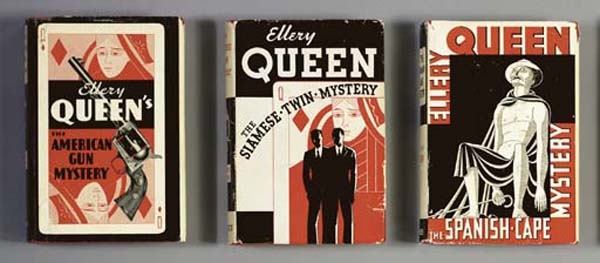

In particular, what about The Dutch Shoe Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Chinese Orange Mystery, and The New Adventures of Ellery Queen? Each of these had sold over 1.2 million copies by 1945. Scarcely anyone today remembers them, or recognizes their author’s name.

Yet eighty years ago they were part of a multimedia franchise. The books bearing the “Ellery Queen” byline were said to have sold over ten million copies by the end of World War II. There was a spinoff juvenile series by “Ellery Queen, Jr.” and some comic books. There were nine Ellery Queen films and a weekly radio series that ran sporadically from 1939 to 1948, along with “Ellery Queen’s Minute Mysteries.” The Queen name adorned countless anthologies of mystery short stories, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, still the most prestigious venue for short mystery fiction, was founded in 1941. You couldn’t visit a newsstand or bookstore without seeing the Queen name.

“Ellery Queen” was the pseudonym of two Brooklyn cousins, Frederic Dannay (né Daniel Nathan) and Manfred B. Lee (né Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky), both born in 1905. While working in advertising, they collaborated on a mystery novel they submitted for a magazine prize. It won, but the magazine went out of business, so The Roman Hat Mystery was brought out as a book in 1929. Dannay and Lee took up detective fiction in earnest, turning out at least one book a year during the 1930s.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Construed most narrowly, the Queen reign lasted from 1929 to 1958, with The Finishing Stroke taking us back to the days of the first novel. The cousins’ biggest bestsellers were 1930s titles reissued during the 1940s boom in paperbacks. Thereafter they were beset by money troubles and poor health, and so were forced to keep turning out product.

After 1958 the result was a bewildering array of books of varying authorship. Lee had a spell of writer’s block, while publishers pressed them for less detection and more straight crime. Ghost writers produced non-Ellery mysteries under the Queen name and historical novels under the Ross pseudonym. Dannay plotted one novel written by a ghost, while Lee was able to rejoin him for other novels such as Face to Face (1967) and their last joint effort A Fine and Private Place (1971). After Lee died in 1971 and Dannay’s wife died a year later, Dannay brought the series to a close.

For many years the books were out of print, but Otto Penzler, always vigilant for ways to keep the great traditions alive, began bringing out uniform editions (including the ghost-written books) in 2018. Before that, probably the most vivid reminder of the saga was the NBC television series of 1975-1976, starring Jim Hutton and David Wayne. I’ve been surprised by the number of people who remember it fondly. But the books? Not so much. Which is a pity.

From cold logic to social comment

In his definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, Francis M. Nevins has argued that the saga develops in four phases. First, there are the pure puzzles–complex crimes demanding elaborate solutions. (Hence the titles flaunting the “mystery” of this or that.) The stories abide strictly by the fair-play principles articulated in Golden Age precept: a careful reader should have all the information necessary to solve the case. The novels flaunted this premise with the famous “Challenge to the Reader” inserted before each climax.

As befits puzzle plots, Phase 1 presents Ellery as a drawling, bloodless intellectual, flaunting his erudition in the manner of the then-popular and more insufferable Philo Vance of S. S. Van Dine. At the same time Lee and Dannay establish some of the devices they’ll use again and again. We encounter cryptic dying messages, missing clues (the dog that doesn’t bark in the nighttime), tempting false solutions, and murderers with a penchant for elaborate crimes. Dannay’s plotting is intricate, but the clarity of Lee’s prose (and his willingness to repeat information) helps the whole contraption work.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

Phase 3 Queen, throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, is generally considered the pinnacle of the series. Endowed with literary ambitions and a range of cultural references, the books showed a new depth of psychological, political, and social sensitivity. In the space I have today, I pick out my favorites, each of which has been considered by one critic or another as Queen’s best. Among their distinctions, they show Dannay experimenting with what we would call “worldmaking” and Lee exploring new stylistic resources. All make invigorating reading today.

“Mr. Queen Discovers America” is the title of the opening chapter of Calamity Town (1942). Ellery gets off the train in Wrightsville, a small New England town. He has come to find a quiet place to write his next novel, and Wrightsville’s apple-pie ordinariness makes it the ideal sanctuary. It’s apparently as pure as the Grover’s Corners of Wilder’s play Our Town (1938) and the idealized Carville of the Andy Hardy movies; the same folksy milieu would figure in William Saroyan’s Human Comedy (book and film, 1943). Ellery manages to rent a house next to the town’s first family, the Wrights, and he’s taken into their social circle.

Quickly the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

In plotting the book, Dannay provided Lee a panorama wider than they had used before. Calamity Town has dozens of named characters, mostly serving as local color but many playing important roles. The mystery itself is less complex than those in Phase 1, but the book is filled out with a cross-section of life in Wrightsville. Low Village is populated by:

people named variously O’Halleran, Zimbruski, Johnson, Dowling, Goldberer, Venuti, Jacquard, Wladislaus, and Broadbeck–journeyman machinists, toolers, assembly-line men, farmers, retailers, hired hands, white and black and brown, with children of unduplicated sizes and degrees of cleanliness. . . . Mr. Queen’s notebook was rich with funny lingos, dinner-pail details, Saturday-night brawls down on Route 16, square dances and hep-cat contests, noon whistles whistling, lots of smoke and laughing and pushing, and the color of America, Wrightsville edition.

This Capraesque vision of vibrant Americana, coming early in the book, is questioned immediately by Lola, the renegade Wright daughter, who calls her town “wormy and damp, a breeding place of nastiness.” Lee’s task is to show both sides of Wrightsville through incidents tracing the town’s reaction to the murder. Ellery is always captivated by the calendar-image look of the place, as when in winter it resembles a Grant Wood painting.

But in town there were people, and sloppy slush, and a meanness in the air; the shops looked pinched and stale, everybody was hurrying through the cold; no one smiled. In the Square they had to stop for traffic; a shopgirl recognized Pat and pointed her out with a lacquered fingernail to a pimpled youth in a leather storm-breaker.

Lee rose to the challenge of portraying the fragility of a social network that can’t respond to a shock to placid lives.

The result is the most wide-ranging and emotionally complex book in the Queen franchise so far. The cousins were unable to sell it for serialization, and from then on, no slick magazines bought a Queen novel for many years.

Class relations and inner turmoil

The Murderer is a Fox (1945) takes Ellery back to Wrightsville, but under very different circumstances. Pilot Davy Fox is welcomed back home for his outstanding record in killing the enemy and rescuing his comrades. But like many a returning vet he has PTSD, which emerges as an urge to strangle his wife Linda. The couple consult Ellery, who speculates that Davy is haunted not just by his combat experiences but by the fact that his father Bayard was imprisoned for poisoning his mother.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

Lee’s solution is to recast his narrational approach, turning the book’s first section into a suspense thriller. For once our viewpoint isn’t initially attached to Ellery. The opening chapters alternate the Fox family awaiting Davy’s train with scenes of Davy on board. All the scenes are deeply subjective, with flashbacks plunging us into the family background and, more harrowingly, Davy’s war experiences. The seamy side of Wrightsville is exposed again and again. Against the bunting and chattering crowd of the train-station homecoming welcome, with the American Legion band “tossing the sun from their silver helmets,” Lee replays Davy’s memories of his father’s shame.

How Davy loathed them, the jeering kids. Because they had known, the whole town knew. The kids and the shopkeepers in High Village and the Country Club crowd and the scrubskinned farmers who drove in on Saturdays to load up–even the hunks and canucks who worked in the Low Village mills. Especially the shop hands of Bayard & Talbot Fox Company, Machinists’ Tools, who merely jeered the more after the Bayard & one day vanished from the side of the factory, leaving a whitewashed gap, like a bandage over a fresh wound.

Asked on the train about the thrills of battle, Davy conjures up:

Being caught on the ground with Zeros twisting and tumbling all over the sky and falling flat on your face in the stinky guck of a Chinese rice field, or pulling Myers out of his cockpit with his stomach lying on his knees after he brought his old P-40 down only God knows how. . . . Having your coffee grinder conk in the middle of a swarm of bandits and belly-landing in scrub on the knife-edged hills–seeing Lew Binks’s coffin drop like lead aflame, and Binks hitting the silk, trustful guy, and then the hornet Japs zapping around him with their spiteful traces hemstitching the sky.

Obliged to evoke the war, Lee summons up a muscular, sometimes lyrical prose unknown in the books of Phases 1 and 2.

Davy’s trauma turns the early chapters into an account of a man driven to murder. Like other novels and films of the 1940s, The Murderer is a Fox shares his nightmares and dissects his compulsion. While a loving, confused Linda tries to lure Davy into an embrace, he struggles to keep away from her.”The game was to stay in his bed. To stay in his bed so that he would not go over to the other bed and obey the prickling of his thumbs. . . . “

The viewpoint shifts to Ellery once he starts to reconstruct how Jessica might have died. In the course of this, family indiscretions are exposed and characterization deepens. In particular, Bayard is revealed as a man of severe principle, who stoically accepts a life sentence of murder. Revealing the true cause of Jessica’s death leads Ellery to a conclusion that could become another Wrightsville scandal. The book ends with Ellery smiling grimly at the prospect of one secret that the town gossip will never exhume.

In Phase 3, Dannay indulged his penchant for elaborate “pattern mysteries,” crimes based on cultural givens like the alphabet, dates of the year, nursery rhymes, and the like. But this ploy demands either a madman (driven by obsession with the pattern) or a super-schemer. Knowing that the pattern would attract the hyperintellectual Ellery, the schemer could then frame someone else as being enslaved to it. Ellery will then confidently call out the wrong suspect, with sometimes dire consequences.

This tendency toward a master-mind, an omniscient “player on the other side,” is at the center of Ten Days’ Wonder (1948). Now a new layer of Wrightsville society is peeled back. Plutocrat Diedrich Van Horn is an industrialist who has indulged his son Howard in every way. But Howard is plagued by bouts of amnesia and tendencies toward suicide. Worse, he has fallen in love with Diedrich’s young wife Sally, and they have committed adultery. A blackmailer has discovered their affair and they are terrified that their love letters will be exposed. Into this Oedipal scenario steps Ellery, whom the couple beg to help them. Against his better judgment, he agrees.

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

“You’ve destroyed me. . . . You’ve destroyed my belief in myself. How can I ever again play little tin god? . . . It’s not in me . . . to gamble with the lives of human beings.”

Dannay planned this bleak book as the last in the Queen saga.

Appropriately, Lee’s prose texture matches the introspective bent of the plot. The subjective narration applied to Davy Fox is now given to Ellery, in a moment-by-moment italicized inner monologue that heightens his reaction to Howard’s and Sally’s situation. Howard says he was the seducer:

“I was the one who made the love, who kissed her eyes, stopped her mouth, carried her into the bedroom.”

Now we show the wound, now we pour salt on it.

Lee’s technique builds up the suspense when Ellery responds mentally to new plot twists.

“Last night there was another robbery.”

Last night there was another robbery.

“There was? But this morning no one said–“

“I didn’t mention it to anyone, Mr. Queen.”

Refocus, but slowly. . . .

“The cash is missing.”

Cash. . .

The inner monologue also passes bitter judgment.

“I could tell him and say I wanted him to divorce Sally and that I’d marry her, and if he hit me I could pick myself up from the floor and say it again.”

I believe you could, Howard. And even get a sort of pleasure from it.

Italicized inner monologues and streams of consciousness became common in popular fiction from the 1920s on, as Perplexing Plots explains. Lee came late to this technique, but he fitted it perfectly to a story that, more deeply than any other, traces the agonizing tensions that confront Ellery as someone meddling in human affairs he doesn’t fully grasp. Dannay said that he designed Ten Days’ Wonder as “an exposure of detective novels and of fictional detectives.”

Cat on the prowl

Between The Murderer is a Fox and Ten Days’ Wonder came a smaller-scale exercise in worldmaking, There Was an Old Woman (1943). Shoe magnate Cornelia Potts rules as eccentric matriarch over a family of ill-assorted children and others. Their estate consists of a gigantic bronze shoe on a pedestal, a tower in which daughter Louella concocts her mad experiments, and a cottage enclosing Horatio, a man who has decided to live in perpetual boyhood. The eldest son Thurlow occupies his time fruitlessly suing outsiders who appear to disrespect him. More normal are the three youngest children Bob, Mac, and Sheila, all despised by old Cornelia.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

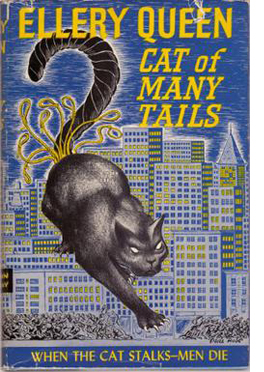

That urge finds its fullest expression in Cat of Many Tails (1949). Bearing the traces of police procedural films like Naked City (1948), this presents a serial killer stalking apparently random victims through Manhattan. Men and women, white and Black, are found strangled with cords of tussah silk. Although he withdrew from criminal affairs after his failure in Ten Days’ Wonder, Ellery is pressed to serve as the public face of the investigation. Facing several million suspects, he is baffled, forced to wander the streets, revisiting the crime scenes obsessively, imagining the victims meeting their fate.

Ellery eventually discloses the pattern behind the killings, but the novel’s development is dominated by a vision of a city under siege and citizens responding in panic. Lee responds with a narrative panorama far exceeding what we saw in his treatment of Wrightsville. He surveys Manhattan neighborhoods high and low. The victims are given detailed lives and routines and backstories; their friends and family are characterized as well. Here is a potential victim’s father:

Frank Pellman Soames was a skinny, squeezed-dry-looking man with the softest, burriest voice. He was a senior clerk at the main post office on Eighth Avenue at 33rd Street and he took his postal responsibilities as solemnly as if he had been called to office by the President himself. Otherwise he was inclined to make little jokes. He invariably brought something home with him after work–a candy bar, a bag of salted peanuts, a few sticks of bubble gum–to be divided among the three younger children with Rhadamanthine exactitude. Sometimes he brought Marilyn a single rosebud done up in green tissue paper. One night he showed up with a giant charlotte russe, enshrined in a cardboard box, for his wife.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

“HE’S HERE!”

Like a stone, it smashed against the great mirror of the audience and the audience shivered and broke. Little cracks widened magically. Where masses had sat or stood, gaps appeared, grew rapidly, splintered in crazy directions. Men began climbing over seats, using their fists. People went down. The police vanished. Trickles of shrieks ran together. Metropol Hall became a great cataract obliterating human sound.

On the platform the Mayor, Frankburner, the Commissioner, were shouting into the public address microphones, jostling one another. Their voices mingled, a faint blend, lost in the uproar.

The aisles were logjammed, people punching, twisting, falling toward the exits. Overhead a balcony rail snapped; a man fell into the orchestra. People were carried down balcony staircases. Some slipped, disappeared. At the upstairs fire exits hordes struggled over a living, shrieking carpet.

Suddenly the whole contained mass found vents and shot out into the streets, into the frozen thousands, in a moment boiling them to frenzy. . . .

Dannay gave Lee the chance to compose scenes of cinematic excitement. No wonder the cousins thought that this novel might sell to the movies.

This extroverted narration is counterweighted by Ellery’s deepest plunge into self-analysis. Once more his proposed solution fails and leads to more deaths, and he is left feeling only a sense of waste. He consults an old psychoanalyst to confirm his conclusion and confess his inadequacy. “I’m too late again. . . . All right, I’m really through this time. I’ll turn my bitchery into less lethal channels. I’m finished, Herr Seligmann.” After consoling him that his efforts were not in vain, Seligmann says: “You have failed before, you will fail again. This is the nature and the role of man.” And he reminds Ellery of humility and mortality: “There is one God; and there is none other but he.” After this, as subsequent novels show, Ellery is able to go on–fallible but still holding to an ideal of truth.

For many critics, Cat of Many Tails is the cousins’ supreme accomplishment, a tour de force of mystery, suspense, and social and psychological observation. Their correspondence shows them at the absolute nadir of their relationship, exchanging long, hurtful letters about their disagreements. Yet their rancorous disputes yielded a novel that holds up better than much crime fiction of the 1940s. It’s a remarkable instance of how the “pure puzzle” story could, over the years, mutate into something rivaling the best of “prestige fiction”–an entertainment that is also an ambitious, moving literary achievement. Many mysteries are forgettable. This one is not.

Other Queen novels of Phase 3 are well worth reading. I’m a particular fan of The Scarlet Letters (1953), where Ellery intuits the solution watching a workman paint the G of “logical” in the sign for the New York Zoological Garden. Nevins considers Phase 4, which includes the more strained and fantastic puzzles of the late years, as of interest but not on a par with 3, and I’d agree. Still, the overall career of two Brooklyn cousins across four decades remains a major achievement of the American detective story, and a powerful lesson in how flexible and engaging popular storytelling can be.

Thanks to members of the UW Filmies for answering questions about their familiarity with Ellery Queen.

My figures on American bestsellers are derived from Alice Payne Hackett, Fifty Years of Best Sellers (Bowker, 1945) and subsequent editions of this book, as well as Frank Luther Mott, Golden Multitudes: The Story of Best Sellers in the United States (Bowker, 1947).

My photo of a masked Lee (or is it Dannay?) comes from the very curious article by Ellery Queen, “To the Queen’s Taste; or, Judge by Formula,” New York Herald Tribune (16 July 1933), F3. Here Queen proposes a 10-point chart for deciding on how good a mystery is. Barnaby Ross beats Agatha Christie.

To Nevins’ definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection should be added the excellent resource Ellery Queen: A Website on Deduction. Another valiant defender of the Queen canon is Jon L. Breen, who wrote a spirited inquiry into why the books have been neglected by contemporary readers. See “The Ellery Queen Mystery” in the Weekly Standard, reprinted in Breen’s lively collection A Shot Rang Out: Selected Mystery Criticism.

Illuminating correspondence between Dannay and Lee is available in Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950 (Perfect Crime, 2012). The informative Wikipedia article lists all the Queen novels, noting the ghosted ones.

A note on names: Dannay and Lee admitted that in their youthful ignorance they didn’t know the slang term queen could refer to a gay man. Ellery, the name of a childhood friend of Dannay’s, evokes New England blue blood. Through the early books, Ellery comes off as a straight WASP. But during Phase 3, Dannay wrote to Lee: “After all, even though we would be subtle about it, the authors of the books are Jews, and in all the deepest senses, so is Ellery Queen the character” (Blood Relations, 93).

A recent example of a film using “Golden Age” principles of fair play is Knives Out, discussed here. I think Lee and Dannay would have approved.

Ellery (Jim Huttton) breaks the fourth wall to extend his “Challenge to the Viewer” in the last episode of the NBC series Ellery Queen Mysteries, “The Adventure of the Disappearing Dagger” (29 February 1976), directed by Jack Arnold.