Searching for surprises, and frites

Saturday | August 8, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Studying film history ought to be continually surprising. Yes, you often find your hunches and assumptions confirmed (which often means it’s time to check them again). But sometimes you find stuff coming out of left field that you had never expected. It would be too pompous to call these items breakthroughs, but every historian knows the little burst of pleasure that comes from seeing something that makes you say: How odd. I didn’t expect that. You might even allow yourself a Wow! now and then.

I was saying wow a fair amount during my two weeks in Brussels this summer. I go regularly, and not just for the moules, frites, and stoemp. I go to the Royal Film Archive, where I study old films. This time I was continuing to pursue some research questions that drove me in 2007 and 2008. What staging and editing strategies are at work in films of the crucial years 1910-1917? How might we explain the continuities and changes we find? I’m a long way from answering these questions fully, but I found some fresh and intriguing instances. One surprise is worth half a dozen confirmations.

Divas on parade

This year I concentrated on European movies. One of the most prominent genres of Italian cinema was the diva film, the movie whose dominant attraction was a beautiful, often fiery, somewhat otherworldly female star.The mesmeric charms of the genre have been celebrated in Peter Delpeut’s anthology film Diva Dolorosa, but the films really need to be seen in their entirety. The most comprehensive book on the subject is Angela Dalle Vacche’s Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema, while my Wisconsin colleague Lea Jacobs has published detailed analyses of diva performance in Theatre to Cinema and here on the web.

In the 1910s, American cinema was turning out fast-paced films, but the diva films I saw provided less complex plots and remarkably protracted acting. An emblematic instance is the climax of Rapsodia Satanica (1917), starring Lyda Borelli. Alba has sold her soul to Mephisto in order to recover her youthful beauty. She toys with two men’s affections, and one kills himself (mysteriously leaving a scar on her face). The plot more or less halts.

Alba retreats into her chateau and wanders the grounds. She glides forlornly through her garden, idles at the piano keys, and drapes herself along a bridge. She strews flowers on the floor and even dresses herself up as a priestess. Most strikingly, she floats into a cluster of mirrors and drapes herself in layers of veils, creating a gauzy shroud.

Run at 16 frames per second, this cadenza of apparitions consumes nearly a minute and a half. Such an exercise in atmospherics might be considered wasteful in an American film of the time, but it enhances the expression of Alba’s late-blooming spirituality—just before Satan comes to claim his pledge.

The same sort of languid choreography can involve other players. The diva’s performance, as Jacobs has shown, is often closer to dance than to orthodox acting, and she can weave arabesques around her more or less stationary suitors. At times the diva is a virtual acrobat. If you can call a contortion graceful, we can find it in the angular wrist maneuvers of Borelli in La Donna Nuda (1914).

The diva’s divagations are usually shot from a distance, and often there are big sets that are cleared of other actors to allow the actress maximum freedom and minimum distraction.At key moments, there might be a straight cut-in to the diva in medium-shot, but the visual narration keeps our attention fixed on a single arresting figure.

This tendency varies from the sort of ensemble staging that I’ve studied in more detail in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. The staging is based upon the diva’s decorative elaboration of her emotional states, rather than in the shifting configuration of several actors. This difference reflects a variation in pace as well: The diva’s subtle changes of expression and posture emerge gradually, but the behavior of actors in ensemble scenes tend to accelerate the flow of action and reaction.

The spotlighting of the diva was not a big surprise, perhaps, but at least a reminder that there are always several tendencies at work in film in any period. More unexpected was the opening sequence of Il Fuoco (1915), in which the heroine visits a lake for a sketching session. As she sits down, a painter arrives to do some painting of his own. There follows a sequence of fourteen shots taken from eleven camera setups, some quite close to the actors. The sequence displays the sort of orthodox continuity that we associate with American films of the same year (The Birth of a Nation, Regeneration, The Cheat).

Granted, European films of the 1910s display freer camera setups in exterior settings than in interior sets. Still, the director of Il Fuoco, Giovanni Pastrone, shows an intuitive mastery of angled shot reverse-shots and consistent eyelines. It makes me eager to see whether other European filmmakers were developing a tradition of continuity editing akin to the American one.

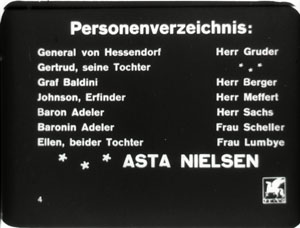

Asta Nielsen was, so to speak, a Danish-German diva. A beanpole with a long face and a slash of a mouth, she might seem an unpromising vessel for languid eroticism. Yet Die Asta became an icon of silent film after her sultry dance in Urban Gad’s Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910) won her an international audience. In Germany she turned out a vast number of dramas and comedies, with her as undisputed main attraction. Lest we think that the term “star” is a modern one, the title card for S1 (1913) is already playing a coy game.

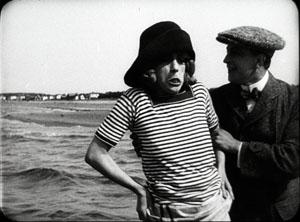

Again, with the spotlight on the heroine, the director’s decision can be simple. Evacuate the set and bring her closer to the camera, or if the set is cluttered, cut in to let Asta act.But she’s refreshingly unethereal, with changes of expression that are fleeting and unpredictable. At a lake with her lover, she flashes her legs at the camera and gives us a grin.

But a few frames later, her grimace becomes downright grotesque as she picks her way to shore. You can easily imagine her fear of losing her balance or stepping on a sharp stone.

Strong-willed and resourceful, Asta projects a wary intelligence. This, of course, doesn’t keep her from falling in love with worthless men.

Colorforms

Today’s archivists are determined to restore silent films to their original beauty, which includes the gorgeous colors achieved by tinting, toning, stencil coloring, and other techniques. Earlier this year Josh Yumibe came to our campus with a splendid collection of frames illustrating the range of possibilities. I saw several colored prints during my Brussels stay, including some original nitrate copies. Two from 1911 were films now acknowledged as “specialist classics.”

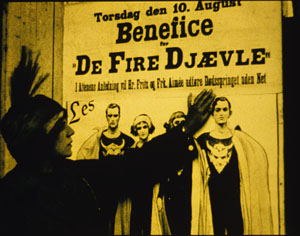

The Four Devils, directed by Robert Dinesen, is one in a cycle of circus films that was popular in Denmark at the period. A team of trapeze artists includes two men and two women; one couple has a steady romance, the other is fractured by the man’s attraction to a rich woman. Once Aimée is convinced of Fritz’s infidelity, she decides to kill him during a performance. The climactic “death leap” is rendered in about thirty shots, including one of an empty trapeze bar swinging. Under the big top, the compositions are full of detail and yet clearly laid out. And Dinesen reveals Aimée’s plan in one of the most ominous shots in silent Danish film.

Even more visually remarkable is Victorin Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (In the Land of Shadows, 1911), a grim naturalistic drama set among coal miners. The film occasionally displays principles of depth staging that would be elaborated in some of the masterpieces of 1913. In one scene, the miners’ families gather in an anteroom. As they wait to identify the men killed in a cave-in, the bodies are barely discernible in the distance.

Au pays de ténébres illustrates a sort of structural usage of color. In scenes like the one above, the color is, in orthodox fashion, denoting a daylight interior. By contrast, the scenes in the mine are tinted blue, the standard hue for night and darkness.

But in the final scenes of the bodies assembled in the room of the dead, the color retains a blue cast, recalling the mine.

Thanks to the tinting, the living find themselves in the land of shadows.

Early auteurs

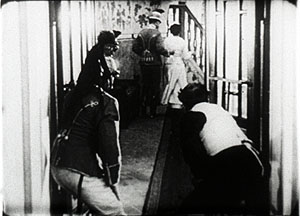

In the 1910s, we can find some distinct directorial approaches. One auteur is the German Franz Hofer, who liked to frame his actors in symmetrical architecture. Rectangular geometries are given a comic cast in Fraulein Piccolo (1915), a story about flirtatious officers and a schoolgirl forced to be both maid and bellboy. Here, two servants open doorways to watch a soldier starting to seduce the heroine.

I hadn’t expected to find surprises in Henri Pouctal’s Chantecoq, a two-part French feature from 1916. Yet this espionage drama was consistently engaging, and not just because the popular comedian Pougaud played the deceptively naïve hero. Pouctal unrolls his scenes in an unusual variety of setups, including an astonishing low-angle view of two spies grappling with Chantecoq on the floor of a train compartment. The image recalls Anthony Mann’s steep railway compositions in The Tall Target.

Alfred Machin was Belgium’s preeminent director of the 1910s. He never seems to have seen a windmill he didn’t want to film, then burn down or blow up. Machin enjoyed recording Belgian folk culture, particularly village dancers, as is evident in classic one-reelers like Le Moulin maudit (The Accursed Mill, 1909), and he had a fondness for jungle cats like Mimur the leopard.

Each of the Machin features I saw shed light on my research questions. Le Diamant noir (The Black Diamond) confirmed that the European tableau style was by 1913 achieving considerable intricacy. In this film, Luc, a rich man’s secretary, is accused of stealing the daughter’s bracelet. The scene of the police interrogation is a muted ballet of figures retreating, advancing, blocking, and revealing.

The servant in the far distance returns to visibility when he’s needed to show the cops to Luc’s room.

In Machin’s La Fille de Delft (The Girl from Delft, 1914), the tableau depth cooperates with some muted cutting. Kate is a famous dancer, visited by Jef, the young shepherd who has loved her since she was a girl. In her dressing room, while stage-door roués wait to take her out for dinner, she gets a message from him.

As she lowers the note, she makes her two playboy admirers more visible; we can see them opening the window.

They peer out, and we get an over-the-shoulder shot of Jef waiting outside.

When we cut back to the master shot, the men are mocking him and Kate is deciding whether or not to admit him. She goes to the window herself and looks outside. Again we get the over-the-shoulder framing, but in two beats: Kate looking, then Kate looking away.

The poignant framing lets us linger on her moment of decision. When she closes the window, we know that she has decided to abandon her childhood friend.

Simpler in its drama and staging is Machin’s official classic, Maudite soit la guerre (Cursed Be War, 1914). Adolphe, a young man from a country suspiciously similar to Germany comes to Belgium, or a place like Belgium, to learn aviation. Adolphe falls in love with his host’s daughter Lidia, but soon war breaks out between their countries and they must part. The rest of the film, which includes some spectacular aerial scenes (and, naturally, a burning windmill), pleads for peace and brotherhood. Released in May of 1914, Machin’s anti-war film now seems a futile warning.

The Archive has restored the original’s Pathécolor, creating images of great loveliness. Some scenes show stenciled color, which helps articulate the planes of shots arrayed in depth. An example surmounts this blog entry. At other moments, deep red tinting enhances the battle scenes, notably one of an exploding dirigible.

In all, this outstanding restoration of Maudite soit la guerre reminds us of what audiences actually saw—films of deeply felt emotion, often accentuated by spectacular action like that on display today, and employing color with both intensity and delicacy.

The restorer’s art

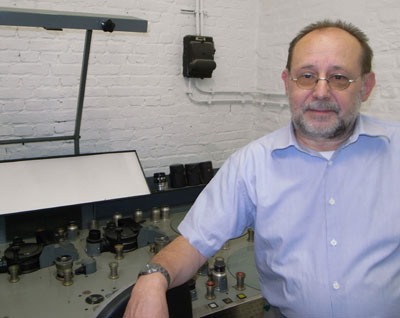

During my stay, I particularly enjoyed the time I spent with Noël Desmet, supervisor of restorations at the Belgian Film Archive. Noël invented the most robust method of recovering silent film color. Around the world, archivists have adopted the Desmet system.

Noël is scheduled to retire in April of next year. His research will be continued by his colleagues, and he will enjoy some well-earned time among his orchids. Film culture rests upon the shoulders of committed archivists like him. Noël Desmet and his peers are the guardians of treasures, the patient preservers of the secrets and surprises harbored by the twentieth century’s most powerful art form.

For more on tableau staging in Europe and the US, see the entries linked above, as well as my notes from this summer’s visit to the Danish Film Archive, some comments on acting styles, my discussion of Charles Barr’s idea of gradation of emphasis, and an entry on hands and faces around a table. The most thorough analyses of these and other staging principles are in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and certain chapters of Poetics of Cinema.

For more information on Machin and Mimur, see the bilingual book edited by Eric de Kuyper, Alfred Machin Cinéaste/ Film-maker (Brussels: Royal Film Archive, 1995).The Diva Dolorosa disc contains extracts from major films, but unfortunately they aren’t specifically identified, and the original cutting patterns aren’t always respected. The difficulty with such celebratory appropriations of silent films is that they are unreliable as historical evidence. Worse, in today’s commercial market, such compilations make it unlikely that other video producers will launch complete DVD versions of the films.

Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, Paul Leni, 1916)

PS 18 August: Thanks to Armin Jäger for a name correction!