Projections on glass

Tuesday | December 22, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

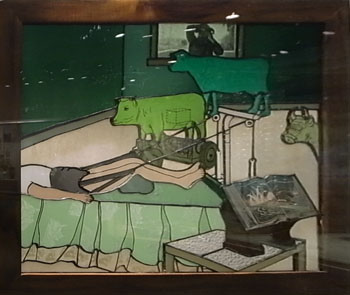

Christa Bothwell, While You Are Sleeping (2007).

Db here:

I must be obsessive. Whenever I get into a museum, I see movies hovering over the exhibits. You want proof? Go here or here or here. Kristin has dabbled in such speculation too, here.

The most recent example came last week. My sister Darlene is recovering from surgery, and as an excursion she, Kristin, and I visited the magnificent Corning Glass Museum in the southeastern tier of New York state. I hadn’t been there since the 1950s, when I was a kid. The museum was flooded in 1972, but after successive, ever more ambitious restorations, it is now a landmark. Its dignified modernist façade houses a sensory extravaganza.

Glass as an artistic medium is usually associated with either well-designed practical objects, like bottles and glassware, or sculpture, as in the Studio Glass movement founded by Harvey Littleton, who worked right here at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Beyond that, what I know about glass you can put in—well, a shot glass. So I was pleased to learn how glass art connects to some issues that interest me about the visual arts generally and film in particular.

Take illusionism. We’re familiar with the ways that the paintings of Dalí and Magritte use the rules of perspective to create hallucinatory landscapes. And we know about classic trompe l’oeil pictures like this seventeenth-century painted letterboard by Cornelis Gijbrechts.

But I didn’t expect to find trompe l’oeil in glass.

This is Cup in Cup (1986) by Ann (Wärff) Wolff . The spectral little cup is inscribed in the surface. Like all good trompe l’oeil, this is best seen from a single standpoint.

Glass is literally all around us, as the stuff of our windows. In a 1976 image, Richard Posner (no, not the judge) creates a film-like scene by leaving crucial information out of frame. Another Look at My Beef with the Government, from the “Picture Window” series, shows him in traction while cattle, and the artist himself outside the window, look on.

This is part of a series called “Picture Window.” The image pictures a window, and it gives us a window onto the scene, but the phrase also suggests that a window can itself be a picture. In this case, it’s Posner’s comment on serving as a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War.

There’s an ongoing debate about whether to consider glass a solid or a very viscous liquid, sort of the ultimate maple syrup. Its fluid qualities make it ideal for evoking movement. Swirls, waves, bursts, and sprouting capillaries are everywhere in the Corning collections. One of the best examples is Littleton’s now-classic Red/Amber Sliced Descending Form (1984).

The slickness of the surfaces lends a palpable wriggling to the snakelike forms of Dale Chihuly’s Cadmium Yellow-Orange Venetian #398 (1990).

Glass makes these coils glisten.

Chihuly was another Madisonian; a more cheerful twisty work graces our campus’s Kohl Center.

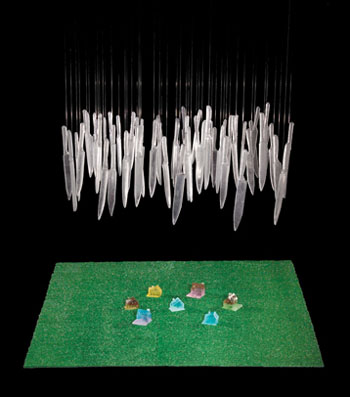

Another sort of movement: Silvia Levinson’s It’s Raining Knives (1996-2004) shows stalactite-like daggers bearing down on a suburban landscape. The slender wires suggest danger hanging by a thread, but they also evoke speed lines, as if the knives are caught in mid-flight.

Levinson is Argentine, and the piece responds to the dictatorship that displaced Juan Perón—during which many of her family vanished or were imprisoned. You can read more about the background to the piece here.

Finally, probably the most filmlike thing I saw: An impression of interrupted movement is combined with an old-fashioned superimposition in Christina Bothwell’s While You Are Sleeping, which surmounts this entry.

After four hours of dazzlement, I was re-persuaded that Eisenstein was right: All the arts are connected, in devious ways, to film.

The Museum has listed many of the items on exhibit, including illustrations, in various pages and pdf files here. Most of the shots here were taken by me, but the Littleton and the Levinson images come from the Museum website.

Coming soon: Our list of the best films of 1919.

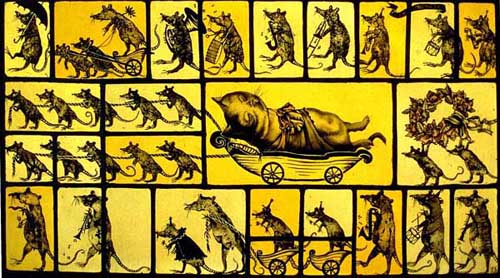

Judith Schaechter, Jazz Funeral for Didi (1994). Not in the Corning collection, but proto-cinematic in a Marey-and-Muybridge way. (And, I admit, reminiscent of Chris Ware.) See other lively Schaechter stained-glass work here and in her book Extra Virgin.