Cannes: Behind the art, hype, and politics

Sunday | June 3, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here–

The Festival de Cannes has been around since 1946, so a sixtieth birthday party this year might seem a bit belated. The festival got off to a rocky start, however, and lack of funds forced its cancellation in 1948 and 1950.

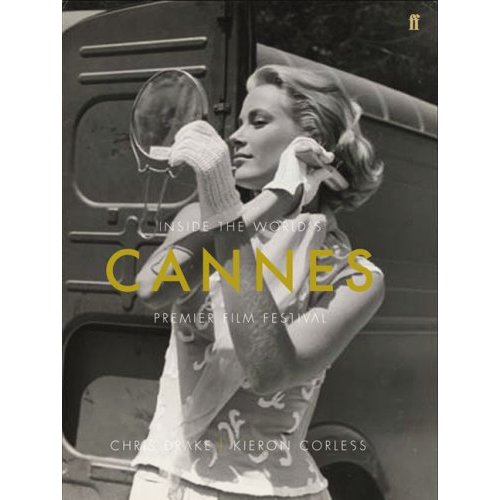

There have been many forms of celebration, but one that is likely to endure is Kieron Corless and Chris Darke’s new history, Cannes: Inside the World’s Premier Film Festival. We picked up a copy in Auckland. The book, published by Faber and Faber this year, is not currently available in the U.S. but is on offer from Amazon’s U.K. branch.

As the authors themselves note, “This is not one of those anecdotal and slightly self-indulgent Cannes memoirs, of which there are several available in English and French” (p. 3). Instead, they avoid the gossipy approach, trying “to redress the balance and probe beneath the surface by telling another story—a counter-history of Cannes, if you will” (p. 2). This is not to say that Cannes is a dry, pedantic look at the event. I found it an absorbing read during the long plane trip from Auckland to Los Angeles. Who wouldn’t enjoy a book whose first chapter begins, “It is tempting to imagine the first Cannes film festival as a Jacques Tati film”? And I wouldn’t call it a counter-history. It’s a solid historical study, well-researched and just the sort of study that any major festival warrants.

The approach is not chronological, though the authors segment the festival’s history into three phases. The first, stretching from 1946 to early 1968, saw Cannes as a platform for international politics, beginning with the Cold War and stretching into the “start of sixties libertarianism.” This period saw the rise of the great auteurs, such as Bergman, Fellini, and Buñuel, whose international reputations owed much to their exposure at the festival.

The second phase begins with the 1968 festival, where the political upheaval in France was enough to close the event down in midstream. In the years that followed, the festival’s organizers strove to become more inclusive, opening up to Third World films and inaugurating the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs to provide a venue for younger, more innovative filmmakers.

Corless and Darke see this phase as ending in 1983, when the opening of the new Palais des Festivals. That event ushered in an era of greater commercialism, more courting of the media, and the introduction of a film market alongside the festival. This third era continues today with the Hollywood studios’ increasing use of Cannes as an opportunity to launch blockbusters shortly before their summer releases.

Although the overall trajectory of the book follows these three phases, the chapters are organized primarily around thematic topics. For example, “Sacred Monsters” examines the increasingly provocative nature of some of the films shown at Cannes in the late 1950s and especially the 1960s. Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Rivette’s La Religieuse created scandals, and the authors use these to show how Catholic censorship affected the festival and how the titillation of more daring subject matter became a means of promoting European films in the U.S.

There is no shortage of anecdotes and discussion of the splashy, glamorous aspects of Cannes. Brigitte Bardot’s 1953 appearance, clad in a bikini and frolicking on the beach, is assessed partly in terms of its impact on her (and Roger Vadim’s) career. But the authors also show how in general starlets manipulated their interactions with more established stars (Kirk Douglas in Bardot’s case) to boost their own publicity value.

One major strand running through the book is the political pressures that frequently underlie the programming at Cannes. A festival launched in the immediate post-World War II years inevitably became a platform where the various countries jockeying for power could display themselves internationally by means of their films. The inclusion of Soviet Russian and later Eastern European movies became a delicate balancing act. The long love-hate relationship between France and the U.S. is traced. Determined to preserve its own culture in the face of competition from the dominant Hollywood product, the French also loved American films and desired the glamour they brought to the festival.

The authors also stress how Cannes’s organizers had to be forced to recognize filmmaking outside the U.S. and Europe by the traumatic shutdown of the 1968 festival. In 1969, Glauber Rocha won the Best Director prize for Antonio das Mortes, Fernando Solanas showed Hour of the Furnaces in the Critics Week program, and Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev—not the official Soviet entry—won the International Critics prize. In 1972, the system of allowing countries to choose their own films for competition was abolished in favor of selection by festival programmers.

A parallel strand considers how conservative Cannes has been through much of its history, both artistically and politically. In early decades, competition programming was done by allotting countries, primarily the U.S. and European nations, a certain number of slots. The countries then chose which titles they would send to fill those slots. Hollywood may have gained a surprisingly prominent place among Cannes’s screenings in recent years, but its films were a major part of the program in the early era as well. Multiple awards were given out in 1946, and honorees included Disney’s The Music Box and Wilder’s Lost Weekend. Wyler’s Friendly Persuasion, of all things, won the Palme d’Or in 1957.

Another sign of conservatism was the fact that major auteurs like Fellini and Bergman did not figure significantly at Cannes until they had already established their reputations. Only in the 1970s, with the post-war generation of filmmakers dying or retiring did the emphasis shift in part to discovering and launching young, unknown directors. Even then, though the book does not mention it, Cannes programmers largely overlooked the emerging 1990s East Asian cinema with China’s Fifth Generation, the New Taiwanese Cinema, and such current Cannes darlings as Wong Kar Wai.

Corless and Darke cannot cover every major event in a complicated history, but they are adept at choosing their case studies to provide a broad overview of the most important trends. Their concluding chapter deals with the immense growth in the number of film festivals and the consequent development of an alternative distribution market apart from theatres. They zero in on Abbas Kiarostami, arguably one of the greatest filmmakers working today but also the perfect exemplar of the “festival film-maker” (pp. 216-227).

The authors have an immense respect for the artistic value of Kiarostami’s work, but they also are clear-eyed in tracing the director’s dependence on Cannes and other festivals. Festivals have allowed him to keep directing in a country where his films have had little local acceptance, either from the government or from audiences. This section also offers an excellent summary of how the vibrant new Iranian filmmaking was brought to the world’s attention through Cannes and how other filmmakers, like Samira Makhmalbaf, have followed in Kiarostami’s wake.

This final chapter goes on to a case study that deals with how dependent on recent American independent cinema Cannes has become. Naturally the authors single out the Weinstein brothers and Miramax, which had their first big hit when sex, lies, and videotape won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1989. As the authors say, “‘Miramax’ also denotes a particular savvy commercial exploitation of independent or art cinema, whose cultural legitimacy and stamp of quality is conferred to a large extent by marketing exploitation of awards scooped at Cannes, which became hugely important to the Weinsteins” (p. 228).

The authors are film journalists and critics of a particularly serious bent. Corless is the deputy editor of Sight & Sound and writes for a variety of English magazines. Darke writes for such outlets as Film Comment, Sight & Sound, and Cahiers du cinéma. Given the drift toward pop entertainment coverage evident in those journals in recent years, the pair are to be congratulated on presenting substantive historical material in such a clear and readable fashion.

Apart from researching the written and filmed record on Cannes, the authors conducted interviews with a wide variety of Cannes organizers, attendees, and commentators. These range from Kiarostami to Tony Rayns to Gilles Jacob (general administrator from 1978 and president from 2000) to Rita Tushingham. (Mike Leigh’s comments are particularly trenchant and revealing, as when he describes Arnold Schwartzenegger’s stealing the spotlight by sweeping up the red carpet at the Cannes screening of Naked—and then disappearing through a side door before the film began.)

The only complaints I have about the book are some lapses in proofreading and a paucity of illustrations. Given the complaints about physical appearance of the 1983 Palais des Festival (nicknamed “the bunker”), it would be helpful to have a photo of it. That could easily have replaced the cluster of director portraits that ends the meager picture gallery.

Film festivals have become crucially important to both the art and business of the cinema, so Corless and Darke’s insights into how Cannes operates are most welcome.