Never too late silents

Monday | August 23, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Underworld

Kristin here:

At last one of the gaping holes in the repertoire of classics on DVD has been filled. Tomorrow the Criterion Collection is releasing a three-disc set of Josef von Sternberg’s three final surviving silent films: Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1927), and The Docks of New York (1928).

Von Sternberg is most famous for his string of films starring Marlene Dietrich, from The Blue Angel in 1930 to The Devil Is a Woman (1935). To me, though, Underworld and The Docks of New York jointly form the summit of his career, with The Last Command a lesser masterpiece in between.

Each beautifully mastered print (slightly window-boxed to assure the correct ratio on a variety of TV sets) comes with two musical accompaniments. Robert Israel has done an original orchestral score for each, with the Alloy Orchestra playing alternatively for Underworld and The Last Command and Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton for The Docks of New York.

David and I were lucky enough to see the first two films with the Alloy Orchestra live at Ebertfest 2008 and 2009. Afterward I asked the trio whether they would consider scoring Docks as well, and they said they were interested. Maybe someday.

I wrote the Ebertfest program notes for Underworld, and I’m reproducing that text here, with minor revisions.

Underworld

Certain years in the history of film stand out for having produced more than their fair share of masterpieces. 1927 was one such year. In the United States alone, there were Buster Keaton’s The General, Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise, Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother, and Josef von Sternberg’s Underworld. On a slightly less exalted plane there were Ernst Lubitsch’s The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg and William Wellman’s Wings, the latter the winner of the first best-picture Oscar.

Such films demonstrate the utter mastery of visual storytelling that American filmmakers had gained over the past decade. Ironically, it was also the year of The Jazz Singer, the hit film that made it inevitable that sound would be used for more than recorded musical accompaniment. The constraints imposed by the crude early sound technology meant that most filmmakers would not regain the flexibility of the silent period for a few years. It’s no wonder that in the early years of the talkies, some filmmakers and theorists felt that sound had ruined an artform that had just come into its own.

Underworld was von Sternberg’s fourth film, and his second surviving one. His first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925), was a slow-paced exercise in grim naturalism, utterly at odds with the style he later developed. We see that style already fully mature in Underworld.

The plot is relatively simple, dealing with a love triangle that develops between gangster “Bull” Weed, the reformed drunkard, “Rolls Royce,” whom he takes on as his right-hand man, and Bull’s girlfriend “Feathers.” (Rolls Royce, Feathers, and their photogenic hats at left.) Von Sternberg tells his story visually, stringing together close-ups that convey the action, close-ups not just of faces but of telling details or gestures that capture the essence of a scene. His editing makes not only for clarity and efficiency, but often for vividness and excitement as well. A contemporary reviewer rightly singled out the virtuoso scene of Bull stealing a bracelet for Feathers: “The jewelry-store hold-up is done in four flashes: a pistol shot smashes a clock set above shelves full of silver; a frightened clerk turns; a hand scrapes diamonds from their cases; a crowd is seen through the store’s plate-glass window … This kind of incisiveness, this giving of the part for the whole, when used imaginatively, not spottily or as a trick, is a method exactly suited to the screen, and one little used.” Exactly. Having seen this quick-cut scene only once, the reviewer missed some shots: there’s one of the clerk by the clock, a cut-in to show a bullet-hole appearing in the glass; back to the clerk as he turns; a close-up of the hand taking the bracelet; a close-up of the floor as an incriminating floor is dropped unnoticed; and a view of the crowd outside scattering. It’s a flashy scene, but von Sternberg’s build-up of conversation scenes from close views is just as confident.

The plot is relatively simple, dealing with a love triangle that develops between gangster “Bull” Weed, the reformed drunkard, “Rolls Royce,” whom he takes on as his right-hand man, and Bull’s girlfriend “Feathers.” (Rolls Royce, Feathers, and their photogenic hats at left.) Von Sternberg tells his story visually, stringing together close-ups that convey the action, close-ups not just of faces but of telling details or gestures that capture the essence of a scene. His editing makes not only for clarity and efficiency, but often for vividness and excitement as well. A contemporary reviewer rightly singled out the virtuoso scene of Bull stealing a bracelet for Feathers: “The jewelry-store hold-up is done in four flashes: a pistol shot smashes a clock set above shelves full of silver; a frightened clerk turns; a hand scrapes diamonds from their cases; a crowd is seen through the store’s plate-glass window … This kind of incisiveness, this giving of the part for the whole, when used imaginatively, not spottily or as a trick, is a method exactly suited to the screen, and one little used.” Exactly. Having seen this quick-cut scene only once, the reviewer missed some shots: there’s one of the clerk by the clock, a cut-in to show a bullet-hole appearing in the glass; back to the clerk as he turns; a close-up of the hand taking the bracelet; a close-up of the floor as an incriminating floor is dropped unnoticed; and a view of the crowd outside scattering. It’s a flashy scene, but von Sternberg’s build-up of conversation scenes from close views is just as confident.

Von Sternberg was obsessed by light, and he was as skilled as anyone who ever worked in Hollywood at “painting” his compositions with the arrangements of lamps, scrims, and reflectors on the set. Today he is remembered most for having used that skill in a series of films he made with Marlene Dietrich, starting with The Blue Angel (1930) and continuing in six more star vehicles made in Hollywood, including Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932). Dietrich would never again look as radiant once she and von Sternberg parted ways. But even before he discovered her, von Sternberg was applying his artistry to far less glamorous actors, in this case George Bancroft, whom the director cast in three silent films and his first talkie, the eccentric but wonderful Thunderbolt (1929).

Apart from being a beautifully made film, Underworld introduced the basic conventions of the gangster genre as we think of it today. There had been plenty of movies including gangsters before 1927, but they were typically the villains. Some films followed the police’s efforts to track down gangsters. Many centered on women unknowingly becoming engaged to a gangster or trying save a relative from blackmail or from becoming a gangster. A very common plot device was to have a heroine’s boyfriend falsely accused of a crime committed by gangsters. None of these films actually made a gangster into the protagonist. With “Bull” Weed, the notion of the “good-bad” man, the sympathetic criminal that William S. Hart had popularized in Westerns, came into the gangster genre. Part of the credit for helping to define the genre goes to the great Ben Hecht, whose original screenplay received Underworld’s only Oscar in the first year those awards were given. (Amazingly, it was not nominated in any other category, even cinematography.) Still, von Sternberg altered the script considerably, much to Hecht’s disgust, and it’s hard to gauge the relative contribution of either man. The later memorable characterization of gangster protagonists by Jimmy Cagney (Public Enemy, 1931, and others), Paul Muni (Scarface, 1932, the plot of which distinctly echoes that of Underworld), and Edward G. Robinson (Little Caesar, 1930) follow directly on from the model created by Underworld.

In a 1968 Swedish television interview (included as a supplement in the Criterion set), von Sternberg admits to having known nothing about gangsters. He gave, he says, “a poet’s idea of gangsterism.” Just one case in point, a close-up of a kitten and some lace curtains as a bullet shatters the glass:

The cracks around the bullet hole echo the patterns in the lace curtains, and the juxtaposition of the fluffy cat and diaphanous cloth emphasize the hardness of the glass and the bullet that pierced it.

The disc also contains a straightforward, informative supplement by Janet Bergstrom, who discusses how von Sternberg’s various failures in the mid-1920s led B. P. Schulberg initially to assign him only to co-direct Underworld. He would look after the visuals and someone else would handle the dramatic action. Fortunately that someone never got hired, and von Sternberg directed the whole thing. He turned out to be an adept director of actors as well, allowing Bancroft, Clive Brook, and Evelyn Brent to create considerable sympathy for three characters involved in a very simple plot.

This film was as much a star vehicle for the highly respected German actor Emil Jannings as it was another opportunity for von Sternberg to polish his style. He plays a Russian general in the Civil War that eventually ended with the Bolsheviks in control. A few years later the general is in exile in Los Angeles, eking out a living as a film extra. It was one of the films that brought Jannings the first Oscar for Best Actor. (Actors could be nominated for multiple films in those early days; Jannings’ other performance was in the lost Way of All Flesh.) Clearly von Sternberg was primarily intrigued by the irony of the central situation: the young revolutionary whom the general had earlier imprisoned (William Powell) is now the director of the film in which he is to play a bit part. The film’s visual style is far less distinctive than those of the other two films in the set.

The long central flashback takes place in Russia, and the historical interior sets for the general’s scenes are conventional Hollywood, big and brightly lit. There are a few atmospheric shots of revolutionary mobs running through the streets at night, but the look is no different from what would expect any such scene in a Hollywood film to look.

The films that had brought Jannings to stardom in the U.S. were The Last Laugh and Variety, and the story line in The Last Command is somewhat similar. A powerful, happy man is abruptly brought low, though here the fall into suffering is far greater. Jannings starts out as a close relative of Tsar Nicholas II and ends, complete with a nervous tic in his face, as an extra, passive in his despair and bullied by the other extras. Ultimately the ex-revolutionary film director has his revenge by forcing the old man to re-enact his old role as a general in a combat scene.

The lengthy final sequence where this revenge is accomplished is the most realistic depiction of studio filmmaking in the late silent period that I have ever seen. We see the two cameras, one for the domestic negative, one for the foreign one. Grips assemble platforms and push big arc spotlights around the set. Earlier, in the opening scene, the Jannings character endures the highly routinized process of obtaining various bits of costume and putting on his makeup.)

The lengthy final sequence where this revenge is accomplished is the most realistic depiction of studio filmmaking in the late silent period that I have ever seen. We see the two cameras, one for the domestic negative, one for the foreign one. Grips assemble platforms and push big arc spotlights around the set. Earlier, in the opening scene, the Jannings character endures the highly routinized process of obtaining various bits of costume and putting on his makeup.)

The film leaves little doubt as to where its sympathies lie in the political conflict at its center. Evelyn Brent plays another revolutionary. Captured by the imperial army, she becomes the general’s mistress to save herself from prison, but she eventually falls in love with him and enables him to escape a lynching by the Reds. By the end, even the bitter, contemptuous director has to admit that the nobly suffering extra was a great man. It’s interesting, by the way, to see Powell playing cold and bitter rather than his usual later urbane and witty persona, and the contrast shows what a fine actor he was.

Though a very worthwhile and skillfully made film, The Last Command ultimately falls short of being on a level with Underworld and The Docks of New York. For one thing, the characters are not nearly as sympathetic as in those two films. Brent and Powell play standard-issue grim revolutionaries, at least until Brent’s character succumbs to love. It’s not clear why they change their minds so radically about the general, given that he is mainly seen having protesting workers mown down, going through show inspections of the troops, and taking advantage of his power over the captive Brent to make her his mistress. Perhaps in an era when the fall of Czarist Russia was deplored and Hollywood saw many exiles looking for work, Jannings’ general could be seen as a tragic figure. To the modern eye, the portrayal of imperialist Russia makes the doomed government seem no better than what was to follow.

The Last Command survives in a somewhat soft print compared with the clarity of the two other films.

The Docks of New York

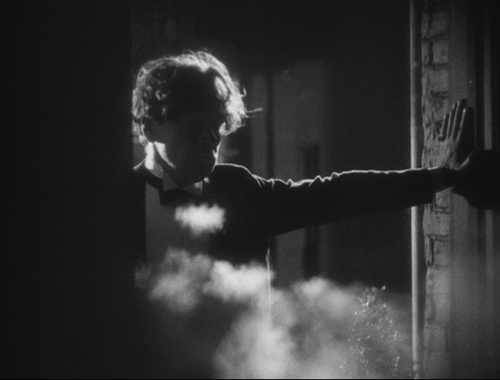

Even more than Underworld, The Docks of New York is a film where almost any shot could yield a dramatic frame enlargement. I’ve made some difficult choices and whittled it down to a few. Let’s just say that it involves a lot of smoke, as in the image immediately below, showing stokers in the engine room of a ship, and a lot of fog, as in the one below it, showing the protagonist’s sidekick looking for him once they’ve gone ashore. Von Sternberg’s well-known predilection for placing elements of the set in the foreground to enhance the composition comes through in both frames. For more fog see the image at the end of this entry.

The film’s story is even simpler than that of Underworld. A Stoker who spends his life at sea with occasional days ashore at various ports save the life of a Girl trying to commit suicide near a seedy dockside tavern. (None of the main characters is given a name.) As she recovers, the pair get to know each other a little. She is presumably a prostitute, he a drifter with, as his tattoos show, a girl in every port. He offers to marry the Girl, and the ceremony takes place in the bar to the amusement of the drunken crowd looking on. The Girl is filled with hope, but the Stoker heads out to sea the next morning. Will he change his mind, or will she despair and successfully drown herself on the next attempt?

The film’s power comes in part through the establishment of the setting: the foggy dock, the rowdy interior of the tavern, and the Girl’s spartan bedroom upstairs, with gulls coming and going on the roof outside the window. Colorful minor characters cluster around the main couple, but they have novital part to play in the drama. The story is compelling largely because of the two leads, especially Betty Compson as the Girl, caught between despair and a reluctant yielding to hope as the kindly Stoker seems to offer her love and relative respectability. Compson had been in films since the mid-1910s, and by the time she retired had made over 200 films. If you’ve seen one of her other films, it’s probably Hitchcock’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith. She played many second female leads in unmemorable films. Yet here von Sternberg guided her to one of the great performances of the silent era. Bancroft is also excellent, though he has the decency not to upstage his co-star. Get out your handkerchiefs for the ending.

In addition to the Bergstrom documentary, there’s a parallel one with Tag Gallagher narrating. Both around 35 minutes long. As a survey of von Sternberg’s silent career, Bergstrom’s is better. Gallagher covers some of the same ground, but he also briefly analyzes the visual style of the films, which might be useful for teachers in preparing a class to watch any of the three films. The Swedish TV documentary also lasts about 35 minutes and covers von Sternberg’s entire career; as is so often the case, the host does not ask the right questions. Despite his reputation for being “difficult” as a director, von Sternberg comes across as quietly charming and modest. The booklet contains program notes by Geoffrey O’Brien, Anton Kaes, and Luc Sante, as well as Hecht’s original short story and information on the musical tracks.

Now if only someone would bring out Thunderbolt on DVD. When I was a newly minted Ph.D. graduate, I taught a survey history course that included Thunderbolt as my example of early sound. Not exactly typical, but Eisenstein and Pudovkin surely would have loved its sound counterpoint, with an offscreen prison jazz group striking up a tune at unexpected moments during the second half.

[Added August 24: Robert Israel has written an informative account of composing the accompaniment for The Docks of New York; it’s posted on Nitrateville. Thanks to Evan Davis for the link.]

Where Roxie Hart got her start

A reporter sets up a dramatic photo of Roxie in Chicago

Last month the folks at Flicker Alley released a restoration of the 1927 film Chicago. It’s the story of Roxie Hart, more familiar from the 1942 Ginger Rogers version, Roxie Hart, and the 2002 musical Chicago. It was signed by director Frank Urson, although tradition has it that Cecil B. De Mille, credited as producer, really directed. The explanation given is that he felt it would hurt his new-found reputation as an upright maker of biblical epics reacently earned with King of Kings (1926).

There’s no decisive proof that De Mille did actually direct Chicago, but film historian Robert S. Birchard musters the evidence in his note “Who Directed Chicago?” in the accompanying booklet.

Chicago is no masterpiece, but it boasts a n entertaining plot and is certainly a polished film, showing off the classical Hollywood style in its mature, late 1920s phase. The continuity is expert, complete with point-of-view shots, short/reverse shot, cutaways. The three-point lighting system is everywhere, giving characters a little glowing outline that at once makes dark figures stand out against dark backgrounds and creates an aura of glamor for the ladies (even in a prison scene.)

The film also contains a technique that Hollywood filmmakers were getting quite good at: significant motifs. There’s a player piano in Roxie’s apartment that comes briefly into the plot numerous times. There are the garters with little bells attached that economically convey first to us and later to Roxie’s husband that she’s having an affair. There are mirrors and watches and, above all ,newspapers.

Given that Underworld and this film were both made in 1927 and set in Chicago, it would be interesting to show them on a double feature. They would probably surprise those people who still consider silent films crude and jerky. Von Sternberg’s film shows how brilliantly and beautifully a story could be told just before sound came in. Chicago, though no masterpiece, would show how good even an ordinary film could be.

The restoration was made from a well-preserved nitrate print in De Mille’s own collection, and it looks great. Most of the extras, both on the second disc and in the booklet, deal with the criminal case on which the various versions are based. It’s an interesting tale, since Maurine Watkins, who wrote the original 1926 play of the same name, started out as a journalist who sensationalized real-life murder cases in order to further her own career. Her treatment of money-grubbing, opportunistic reporters in effect satirizes herself. She kept secret her life as a journalist, but she was unable to duplicate her success as a playwright and ended up a minor scriptwriter in Hollywood.

Other supplements cover flappers and the 1920s jazz age, but there is little on the film itself.

The Docks of New York