Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

The ten best films of … 1920

High and Dizzy

Kristin here:

Three years ago, we saluted the ninetieth anniversary of what was arguably the year when the classical Hollywood cinema emerged in its full form. The stylistic guidelines that had been slowly formulated over the past decade or so gelled in 1917. We included a list of what we thought were the ten best surviving films of that year.

In 2008 we again posted another ten-best list, again for ninety years ago. This annual feature has become our alternative to the ubiquitous 10-best-films-of-2010 lists that print and online journalist love to publish at year’s end. It’s fun, and readers and teachers seem to find our lists a helpful guide for choosing unfamiliar films for personal viewing or for teaching cinema history. (The 1919 entry is here.)

There were many wonderful films released in 1920, but, as with 1918, I’ve had a little trouble coming up with the ten most outstanding ones. Some choices are obvious. I’ve known all along that Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans (finished by Clarence Brown when Tourneur was injured) would figure prominently here. There are old warhorses like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Way Down East that couldn’t be left off—not that I would want to.

But after coming up with seven titles (eight, really, since I’ve snuck in two William C. de Mille films), I was left with a bunch of others that didn’t quite seem up to the same level. Sure, John Ford’s Just Pals is a charming film, but a world-class masterpiece? A few directors made some of their lesser films in 1920, as with Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow or Lubitsch’s Sumurun. Seeing Frank Borzage’s legendary Humoresque for the first time, I was disappointed—especially when comparing it with the marvelous Lazy Bones of 1924. (Assuming we continue these annual lists, expect Borzage to show up a lot.) Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1920, and Keaton and Lloyd were still making shorts, albeit inspired shorts. Mary Pickford’s only film of the year, the clever and touching Suds, is a worthy also-ran. Choosing Barrabas over The Parson’s Widow or Why Change Your Wife? over Sumurun has a certain flip-of-the-coin arbitrariness, but we wanted to keep the list manageable. But they all repay watching.

The year 1920 can be thought of as a sort of calm before the storm. In Hollywood a new generation was about to come to prominence. Griffith would decline (Way Down East may be his last film to figure on our lists). Borzage will soon reach his prime, as will Ford. Howard Hawks will launch his career, and King Vidor will become a major director. The great three comics, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd will move into features. In other countries, an enormous flowering of new talent will appear or gain a higher profile: Murnau, Lang, Pabst, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dozhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Jean Epstein, Pabst, Hitchcock, and others. The experimental cinema will be invented, and Lotte Reiniger will devise her own distinctive form of animation. Watch for them all in future lists, which will be increasingly difficult to concoct

In the meantime, here’s this year’s ten (with two smuggled in). Unfortunately, some of these films are not available on DVD. They should be.

The great French emigré director Maurice Tourneur figured here last year for his 1919 film Victory. The Last of the Mohicans is just as good, if not better. I haven’t read the Cooper novel, set during the French and Indian War, but it’s obvious that Tourneur has pared down and changed the plot considerably. The sister, Alice, is made a less important character, with the plot focusing on two threads: the Indian attack on the British population as they leave their surrendered fort and on the virtually unspoken attraction between the heroine Cora and the Mohican Indian Uncas. The seemingly impassive gazes between these characters, forced to conceal their attraction, convey more passion than many more effusive performances of the silent period. The actress playing Cora also wore less makeup than was conventional, de-glamorizing her and making her a more convincing frontier heroine.

The film is remarkable for its gorgeous photography, with spectacular location landscapes, some apparently shot in Yosemite (below left). Tourneur’s signature compositional technique of shooting through a foreground doorway or cave opening or other aperture appears frequently (below right). (Brown’s account of the filming in Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By makes it sound as though he shot most of the picture, but in watching the film I find this hard to believe.)

Finally, the film stands out from most Hollywood films of its day for its uncompromising depiction of the ruthless violence of the conflict between the British and those Indians allied with the French. The scene in which the inhabitants of the fort leave under an assumed truce and are massacred can still create considerable suspense today, and the outcome puts paid to the notion that all Hollywood films end happily.

The word melodrama gets tossed around a lot, and many would think of much of D. W. Griffith’s output as consisting of little besides melodramas. But Way Down East is the quintessential film melodrama. An innocent young woman (Lillian Gish) is lured into a mock marriage and ends up deserted and with a baby. The baby dies and she finds a place as a servant to a large country family, where the son (Richard Barthelmess) falls in love with her. Her sinful status as an unwed mother leads the family patriarch to order her out, literally into the stormy night. She ends up on an ice flow, headed toward a waterfall. Along the way there’s comic relief from some country bumpkins and a naive professor who falls for the hero’s sister. It all works, partly because Griffith treats the main plot with dead seriousness and partly because Gish elicits considerable sympathy for her character.

Not only is it a great film, but it provides a window into the past, preserving a popular nineteenth-century play and giving insight into the drama of that era. It’s hard to think of another feature film that conveys such a genuine record of the Victorian theater, directed by a man who had made his start on the stage of the same period. (Unfortunately the film does not survive complete. The Kino version linked above is from the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration, which provides intertitles to explain what happens during missing scenes.)

Way Down East displayed a conservative attitude toward sex that was rapidly receding into the past–at least as far as the movies were concerned. The same year saw two films that set the tone for the Roaring ’20s in their more risqué depiction of romantic relationships: Cecil B. De Mille’s Why Change Your Wife? and Mauritz Stiller’s frankly titled Swedish comedy Erotikon.

De Mille has featured on our previous lists, for Old Wives for New in 1918 and Male and Female in 1919. Why Change Your Wife? ramped up the sexual aspect of the plot, however, as a Photoplay reviewer made clear: “”Having achieved a reputation as the great modern concocter of the sex stew by adding a piquant dash here and there to Don’t Change Your Husband, and a little more to Male and Female, he spills the spice box into Why Change Your Wife?” The plot is not nearly as daring as this suggests. Gloria Swanson plays a wife who is straight-laced and intellectual, driving her husband to spend time with a stylish woman who tries to seduce him. Yet he flees after one kiss, and after his wife divorces him on the assumption that he has cheated on her, he marries the seductress. The heroine discovers the error of her ways and becomes sexy in her dress and behavior. As a result the husband regains his old love for her, and they remarry. No actual adultery occurs, and the first marriage is affirmed with a happy ending.

Why Change Your Wife? may have seemed more daring because De Mille here externalizes the shifting relationships through the costumes to the point where no viewer could miss the implications. Initially the wife’s demure dresses mark her as prudish, while the woman who lures her husband away is dressed like a vamp. Once the wife lets go, she dons similar revealing, expensive designer clothes. As a result, the male members of the audience might revel in a fantasy of their ideal wife, and the women would delight in displays of fashions most of them could never own in reality. It proved a successful combination. We tend to forget it now, but the 1920s was full of variants and imitations of Why Change Your Wife?, often featuring a fashion-show scene that was nothing but a parade of models in outlandish clothes. (Early Technicolor was sometimes shone off in such sequences.) Top designers like Erté were recruited to bring their talents to such films.

Fashion as a selling point in films remains with us. The glossy new version of The Hollywood Reporter, recently decried by David, now has a regular “Hollywood Style” section. The November 24 issue ran “Costumes of The King’s Speech,” and the December 1 issue describes “Fashions of The Tourist,” with photos of Angelina Jolie in her various costumes. In addition to shots of the stars, both articles feature enticing close-ups of lipstick, shoes, jewelry,and purses.

A double feature of Why Change Your Wife? and Erotikon would provide a vivid sense of the differing moral outlooks of mainstream America and Europe in the post-war years. In Erotikon, the situation is reversed. An absent-minded entomologist neglects  his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

Erotikon reflects some of the influences from Hollywood that were seeping into European films after the war. Sets are larger, cuts more frequent (though not always respecting the axis of action), and three-point lighting crops up occasionally. Yet Stiller maintains the strengths of the Scandinavian cinema of the 1910s, with skillful depth staging (left) and a dramatic use of a mirror. In the opening of a crucial scene where the sculptor confronts the wife with her adultery, tension builds because she does not know he is watching her until she sees him in the mirror (see bottom). Still, apart from its European sophistication, Erotikon could pass for an American film of the same era. Stiller and lead actor Lars Hansen would both be working in Hollywood by the mid-1920s.

I can’t allow the nearly unknown director William C. de Mille to take up two slots this year, though it’s tempting. William’s career was shorter than that of his much better-known brother Cecil. It peaked in 1920 and 1921, though, and I still look back fondly on the films by him that were shown in “La Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival of 1991. That year saw a large retrospective of Cecil’s films, and the organizers wisely decided to include a  sampling of William’s surviving work.

sampling of William’s surviving work.

The two men’s approaches were markedly different. Where Cecil by this point was setting his films among the rich and using visual means like costumes to make the action crystal-clear to the audience, William was more likely to favor middle-class settings with small dramas laced with humor and presented with restrained acting and small props. Despite William’s skill as a director and his ability to create sympathy for his characters, he never gained much prominence, especially compared to his brother. He retired from filmmaking in 1932, at the relatively young age of 54. Yet obviously he was attuned to his brother’s style, having written the script for Why Change Your Wife? It may be characteristic of the two that Cecil capitalized the De in De Mille, while William didn’t.

Relatively few of William’s films survive, but these include two excellent films from 1920, Jack Straw and Conrad in Quest of His Youth. I don’t remember Jack Straw well enough to describe it. It involved the hero’s falling in love with a woman when they both live in the same Harlem apartment building. When her family becomes rich, Straw disguises himself as the Archduke of Pomerania in order to woo her. Sort of a Ruritanian romance but played out in the U.S.

I remember Conrad in Quest of His Youth better. The hero returns from serving as a soldier in India. He feels old and decides to try and recover his youth. The first attempt comes when he and three cousins agree to return to their childhood home and indulge themselves in the simple pleasures of their youth. Eating porridge for breakfast is a treasured memory, but the group discovers that this and other delights are no longer enjoyable to them as adults. Conrad goes on to seek romance elsewhere and eventually finds a woman who makes him feel young again. The film’s poignant early section manages in a way that I’ve never see in any other film to convey both nostalgia for the joys of childhood and the sad impossibility of recapturing them.

Neither film is available on DVD. Indeed, I couldn’t find an image from either to use as an illustration. The only picture I located is a rather uninformative one from Conrad in Quest of His Youth, above right, which I scanned from William C.’s autobiography (Hollywood Saga, 1939). It’s no doubt an indicator of William’s modesty that the frontispiece of this book is a picture of his brother directing a film.

Maybe this entry will serve as a hint to one of the DVD companies specializing in silent movies that these two titles deserve to be made available. They’re high on my list of films I would love to see again.

Most people who study film history see Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari very early on, though they probably push it to the backs of their minds later on. I have a special fondness for Caligari precisely because I did see it early on. I took my first film course, a survey history of cinema, during my junior year. Maybe I would have gotten hooked and gone on to graduate school in cinema studies anyway, but it was Caligari that initially fascinated me. It was simply so different from any other films I had seen in what I suddenly realized was my limited movie-going experience. It inspired me to go to the library to look up more about it, a tiny exercise in film research.

Some may condemn it as stage-bound or static. Despite its painted canvas sets and heavy makeup, however, it’s not really like a stage play. Many of the sets are conceived of as representing deep space, though often only with a false perspective achieved by those painted sets:

Still, in an era when experimental cinema was largely unknown, Caligari was a bold attempt to bring a modernist movement from the other arts, Expressionism, into the cinema. It succeeded, too, and inaugurated a stylistic movement that we still study today.

I haven’t watched Caligari in years (I think I know it by heart), but I’m still fond of it. The plot is clever grand guignol. It has three of the great actors of the Expressionist cinema, Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Lil Dagover, demonstrating just what this new performance style should look like. The frame story retains the ability to start arguments. The set designs area dramatically original, and muted versions of them have shown up in the occasional film ever since 1920. Even if you don’t like it, Caligari can lay claim to being the most stylistically innovative film of its year.

As I did for our 1918 ten-best, I’m cheating a bit by filling one slot of the ten with a pair of shorts by two of the great comics of the silent period. Both have matured considerably in the intervening two years. In 1918, Harold Lloyd was still working out his “glasses” character. By this point he is much closer to working with his more familiar persona. Similarly, in 1918, Buster Keaton was still playing a somewhat subordinate role in partnership with Fatty Arbuckle. In 1920, he made his first five solo shorts, co-directing them with Eddy Cline.

The Lloyd film I’ve chosen is High and Dizzy, the second short in which he went for “thrill comedy” by staging part of the action high up on the side of a building. (See the image at the top.) Four years later he would build a feature-length plot around a climb up such a building in Safety Last, one of his most popular films. In High and Dizzy, Harold is not quite the brash (or shy) young man he would soon settle on as the two variants his basic persona. The opening shows him as a young doctor in need of patients. He soon falls in love with the heroine, and through a drunken adventure, ends up in the same building where she lies asleep. She sleepwalks along a ledge outside her window, and when Harold goes out to rescue her, she returns to her bedroom and unwittingly locks him out on the ledge. The film is included in the essential “Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection” box-set, or on one of the two discs in Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” Vol. 2.”

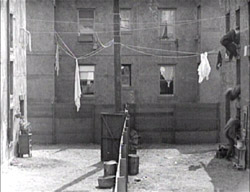

Neighbors was the fifth of the five Keaton/Cline shorts made in 1920. (It was actually released in early 1921, but I’ll cheat a little more here; there are other Keaton films to come in next year’s list.) It’s a Romeo and Juliet story of Keaton as a boy in one working-class apartment house who loves a girl in a mirror-image house opposite it. Two bare, flat yards with a board fence running exactly halfway between them separate the lovers. Naturally the two sets of parents are enemies.

Lots of good comedy goes on inside the apartment blocks, but the symmetrical backyards and the fence inspire Keaton. We soon realize that his instinctive ability to spread his action up the screen as well as across it was already at play. The action is often observed straight-on from a camera position directly above the fence, so that we–but usually not the characters–can see what’s happening on both sides. For one extended scene involving policemen, Keaton perches unseen high above them, hidden. Even though we can’t see him, the directors keep the framing far enough back that the place where we know he’s lurking is at the top of the frame as we watch the action unfold. The playful treatment of the yard culminates in an astonishingly acrobatic gag that brings in Keaton’s early music-hall talents.

The boy and girl have just tried to get married, but her irate father has dragged her home and imprisoned her in a third-floor room. She signals to Keaton, across from her in an identical third-floor window. A scene follows in which two men appear from first- and second-story windows below Keaton, and he climbs onto the shoulders of the two men below. This human tower crosses the yard several times, attempting to rescue the girl; each time they reach the other side, they hide by diving through their respective windows:

They perform similar acrobatics on the return trips to the left side, carrying the bride’s suitcase or fleeing after her father suddenly appears.

Neighbors is included as one of two shorts accompanying Seven Chances in the Kino series of Keaton DVDs, available as a group in a box-set.

Our final two films lie more in David’s areas of expertise than mine, so at this point I turn this entry over to him.

DB here:

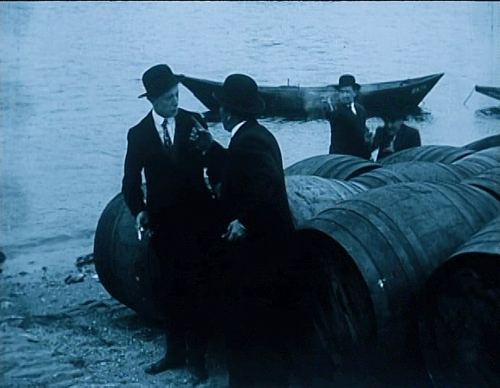

With Barrabas Feuillade says farewell to the crime serial. Now the mysterious gang is more respectable, hiding its chicanery behind a commercial bank. Sounds familiar today. As Brecht asked: What is robbing a bank compared with founding a bank?

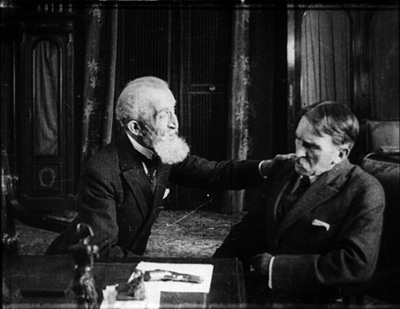

Over it all towers another mastermind, the purported banker Rudolph Strelitz. In his preparatory notes Feuillade called him “a sort of sadistic madman, a virtuoso of crime . . . a dilettante of evil.” Against Strelitz and his Barrabas network are aligned the lawyer Jacques Varèse, the journalist Raoul de Nérac (played by reliable Édouard Mathé), and the inevitable comic sidekick, once again Biscot (so perky in Tih Minh).

The film’s seven-plus hours (or more, depending on the projection rate) run through the usual abductions, murders, impersonations, coded messages, and chases. But there’s little sense of the adventurous larking one finds in Tih Minh (1919), in which the hapless villains keep losing to our heroes. The tone of Barrabas is set early on, when Strelitz forces an ex-convict into murder, using the letters of the man’s dead son as bait. The man is guillotined. The epilogue rounds things off with a series of happily-ever-afters in the manner of Tih Minh, but these don’t dispel, at least for me, the grim schemes that Strelitz looses on a society devastated by the war. Add a whiff of anti-Semitism (the Prologue is called “The Wandering Jew’s Mistress”), and the film can hardly seem vivacious.

According to Jacques Champreux, Barrabas was the first installment film for which Feuillade prepared something like a complete scenario, although it evidently seldom described shots in detail. The film has a quick editing pace (the Prologue averages about three seconds per shot), but that is largely due to the numerous dialogue titles that interrupt continuous takes. With nearly twenty characters playing significant roles and some flashbacks to provide backstory, there’s a lot of information to communicate.

Of stylistic interest is Feuillade’s movement away from the commanding use of depth we find in Fantômas and other of his previous masterworks. Here the staging is mostly lateral, stretching actors across the frame. Very often characters are simply captured in two-shot and the titles do the work, as if Feuillade were making talking pictures without sound. Once in a while we do get concise shifting and rebalancing of figures, usually around doorways. Here Jacques vows to go to Cannes and tell the police of the kidnapping of his sister. As Raoul and Biscot start to leave, Jacques pivots and says goodbye to Noëlle, creating a simple but touching moment of stasis to cap the scene.

Full of incident but rather joyless, Barrabas will never achieve the popularity among cinephiles of the more delirious installment-films, but it remains a remarkable achievement. The ciné-romans that would follow until Feuillade’s death in 1925 would lack its whiff of brimstone. They would mostly be melodramatic Dickensian tales of lost children, secret parents, strayed messages, and faithful lovers. Barrabas is not available on DVD.

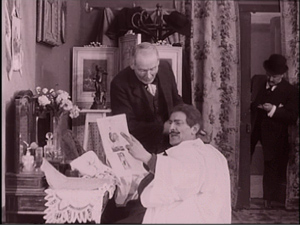

You might think that a movie that opens with a frowning old man studying a skeleton would also be somewhat unhappy fare. Such isn’t actually the case with Victor Sjöström’s generous-hearted Mästerman, a story of a village pawnbroker obliged to take a young woman as a housekeeper. With his stovepipe hat and air of sour disdain, Samuel Eneman, known to the village as Mästerman, is a ripe candidate for rehabilitation. Once Tora is installed and has put a birdcage (that silent-cinema icon of trapped womanhood) on the window sill, the scene is set for Mästerman’s return to fellow feeling. But she is there merely to cover the debts and crime of her sailor boyfriend, and eventually Eneman realizes he must make way for young love. The drama is played out in front of the townspeople, and as often happens in Nordic cinema (e.g., Day of Wrath, Breaking the Waves) the community plays a central role in judging, or misjudging, the vicissitudes of passion.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

For a valuable source on Feuillade’s preparation for Barrabas and other of his works see Jacques Champreux, “Les Films à episodes de Louis Feuillade,” in 1895 (October 2000), special issue on Feuillade, pp. 160-165. I discuss Feuillade’s adoption of editing elsewhere on this site.

Tom Gunning provides an in-depth discussion of Sjöström’s style at this period in “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, ed. John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), pp.204-231. For more on some of the directors discussed in this entry, check the category list on the right.

Erotikon.

How to watch FANTÔMAS, and why

DB here:

He is, we’re told in the opening of the first volume, “The Genius of Crime.” Not a genius, the genius. And he doesn’t play nice.

“Fantômas.”

“What did you say?”

“I said: Fantômas.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Nothing. . . . Everything!”

“But what is it?”

“Nobody. . . . And yet it is somebody!”

“And what does the somebody do?”

“Spread terror!”

In the standard English translation, the last line sounds exceptionally scary, especially today. The original French, “Il fait peur,” is closer to “He creates fear,” but that sounds tamer in English than in French.

In whatever language, for a hundred years this catechism has proven bone-chilling. Cinephiles, crime fans, avant-garde artists, and mass audiences have found the tales anxiety-provoking, even hallucinatory. The delirious imagery and plot twists are felt to harbor a demented poetry. So the first reason to celebrate the arrival of a U. S. DVD version of Louis Feuillade’s great installment-film Fantômas (1913-1914) is that we can all have a look at what made Apollinaire and Magritte and Resnais and Robert Desnos tremble.

I confess myself of the other party. I enjoy tales of Fantômas and Dr. Gar-el-Hama (the Danish equivalent in movies of the era) and Dr. Mabuse and Haghi (of Lang’s magnificent Spione, 1928) but they don’t give me an existential frisson, or unmoor me from rationality, or make me feel the secret currents swirling through the modern city. Call me cold-blooded.

On second thought, don’t. The best-made efforts in the master-mind genre do heat my blood—but because they arouse my love of narrative invention and dazzle me with flourishes of cinematic style. The conventions of the genre, all the disguises and elaborate schemes and surprising revelations engineered by the Genius behind the scenes, the cascades of coincidence and the hairbreadth escapes, aren’t merely enjoyable in themselves. They show how little plausibility matters to storytelling. (People may say they like realism, but they’re suckers for far-fetched stories.) And in order to make the whole farrago of traps and conspiracies flow along, you need filmmakers who can hold our interest with swift pacing and ingenious narration. On many occasions, depicting virtuosity of crime has called forth virtuoso cinematic technique.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

Thirty-two Fantômas novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre were published from 1911 through 1913. By the time Feuillade launched the film version in May of 1913, the book cycle was winding down; in La Fin du Fantômas (1913), the master criminal dies, at least for a while. Souvestre died in 1914, but the prodigious Allain revived the series and the villain during the 1920s.

When the films were made, Feuillade was working for Gaumont, one of the two most powerful French studios. He was head of production, overseeing other directors while turning out his own movies at a rapid clip. He signed over fifty films, mostly one-reel shorts, in 1913 alone. The Fantômas films are often thought of as a serial, but they are really long installments in a series, somewhat like our Bond and Bourne franchises. A “feature” film at the period might run fifty to seventy-five minutes. As with our franchises, there are recurring characters. The films pit police inspector Juve and the journalist Fandor against Fantômas and his accomplices, notably the treacherous but passionate Lady Beltham.

Feuillade was one of the great directors. He had a fine comic touch, not only in the shorts featuring child players like Bébé and Bout de Zan but also in farcical two-reelers like Les Millions de la bonne (The Maid’s Millions, 1913). His dramas could be powerful too, epitomized for me in the two-part feature Vendemiaire (1919) and sentimental melodramas like Les Deux Gamines (1921) and Parisette (1922). Still, he’ll probably always be most famous for his crime films like Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), Tih Minh (1919), and of course the first of them, Fantômas.

The new video edition, which comes to us from Kino, is the third DVD release I’ve seen. The first was a French set from Gaumont in 1998, the first full year of the DVD format. The box contains a handsome booklet with background material, pictures, and an interview with Feuillade, but the intertitles aren’t translated. All subsequent releases seem to be based on the Gaumont copy used in this collection. That results in so-so picture quality, a rather haphazard score pasted together from classical pieces, and occasional distracting sounds, like birds tweeting in outdoor scenes. The UK Artificial Eye PAL release of 2006 includes a brief introduction by Kim Newman but no booklet. The original Gaumont titles are preserved, with English subtitles added.

Kino’s version unfortunately eliminates the French titles altogether, substituting English translations. Visually, however, I prefer the Kino version to the others, which on my monitors is less contrasty and heavily saturated in its tinting. Still, the Gaumont master was made in the early days of DVD authoring and could stand a complete redo. In fact, Gaumont should release many more Feuillade titles, starting of course with Tih Minh.

How best to persuade you that these movies are worth watching? I decided to concentrate on just the first episode, Fantômas (aka The Shadow of the Guillotine) as a sample of Feuillade’s artistry. Everything I analyze here is on display in later installments, sometimes more flamboyantly. The creative principles at work are explored in greater detail in my books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light (which has a long chapter on Feuillade), as well as in several items on this site.

1. Get ready for preposterousness. The film, based on the first book in the series, rearranges the novel’s plot order considerably and simply excises the first half’s major line of action, a hideous murder. Even with cuts, though, the film asks us to believe that after Fantômas, disguised as one Gurn, is put into prison, he can get his wealthy mistress to bribe a guard to let him out for a while. And that during their rendezvous, the couple can replace the murderer with an actor who happens to be playing Gurn in a stage show based on the case. And that the actor, having been drugged, can’t recall his identity.

There’s at least one glaring plot gap in the film. Juve solves the mystery of the disappearance of Lord Beltham when he discovers his body in a steamer trunk about to be sent overseas. The novel explains his rather tenuous line of reasoning (Chapter 11), but the film simply shows him arriving at Gurn’s apartment and examining the fatal trunk. Presumably, though, Feuillade could afford to be elliptical. Some of the audience would have known the novels and could fill in bits that seem enigmatic to us.

The film’s climax is in fact less implausible than the novel’s, perhaps out of considerations of good taste. In the novel, the actor substituted for Gurn actually dies at the guillotine; the authorities realize their mistake only when they see the head smeared with greasepaint. In the film, Juve interrogates the dazed Valgrand and astounds other officials by revealing that he isn’t the prisoner they had locked up. Even then, it seems unlikely that nobody but Juve would have noticed the prisoner’s wig and false mustache.

Far-fetchedness is built into the genre, so the problem is handling. Craziness must be treated matter-of-factly, and Feuillade’s sober technique takes all the wild developments in its stride. Nothing fazes Fantômas, or our director.

2. Accept the conventions of “pre-classical” cinema. Film historians often consider the years from 1907 to 1917 as leading up to the sort of cinematic storytelling we know, replete with lots of cutting, close-ups, and camera movements. A film like Fantômas exemplifies some tendencies of French cinema in this period. There is relatively little crosscutting among lines of action. The film uses no shot/ reverse-shot or extended passages of close-ups. Typically a cut is used to enlarge printed matter, like a news story or a business card, or to emphasize crucial details. Here is Juve discovering a clue, Gurn’s hat, in Lady Beltham’s parlor.

Interior sets were usually designed to be seen from only one camera orientation. In exteriors, we get somewhat freer cutting, presumably because real surroundings don’t confine the camera as much as a fake set does.

In this transitional era, some habits of earlier years hang on: the fairly distant framings, the fairly obvious sets, and the occasional glances at the audience.

You can almost sense stylistic change happening during such moments. In earlier films, characters constantly looked at the audience, but in Fantômas a character’s eyes pause fractionally on us before drifting away, as if the look to the camera simply signified thinking, not an effort to share a response.

Similarly, Feuillade seems to be sensing the need for varying his camera positions in a way that we’d find in later cinema. Consider his handling of the Royal-Palace Hotel.

To show the elevator entry on different floors he reuses the same set. This is motivated realistically, since hotels look more or less the same on different floors. But if the camera were framing every elevator shot exactly the same way, we would have weird jump cuts when cutting from floor to floor, and the use of the same set would be more apparent. So Feuillade not only re-labels each landing at the top of the frame, but he shifts his camera position slightly, moving the framing rightward in the string of shots showing the elevator descending to the ground floor.

The slight shifts in framing reinforce the sense that we’re on different floors.

3. Watch the back door. Deep space is common in exteriors from the beginning of cinema, even in Lumière shorts, but by the early 1910s filmmakers were starting to replace relatively flat interior sets with ones that give their actors more playing space in depth. Here, for example, is a Bohemian party from Feuillade’s Une Nuit agitée of 1908. The parlor and the action are shot in a flat, lateral way, and people enter the room from the right or left.

Compare the depth in the interiors of many scenes in Fantômas of five years later.

Once sets become deeper, the rear door becomes very handy for entrances and exits, and Feuillade is a master of using it. It’s usually fairly close to the center, but in the actor Valgrand’s dressing room, it’s off to the side.

The rear door prepares us for upcoming action and provides another center of compositional interest—advantages that don’t come up when actors enter from the sides of the frame. The door also allows people to be shown overhearing what is going on in the foreground.

4. It isn’t theatre! There’s a common belief that the cinema of this period simply records performances as if on a stage. But that’s not true. As most of these shots show, the camera is usually closer than any spectator would be to a stage play. Feuillade reminds us of what a real stage performance would look like when Lady Beltham sees the actor Valgrand in the dramatization of Gurn’s capture. (It’s reminiscent of the stage-like set in Une Nuit agitée above.)

Valgrand’s gestures are broad ones, suitable to being seen from a great distance. But in the surrounding story, the performances are much more subdued. Feuillade demanded dry, quick acting from his players, and their gestures aren’t extravagant. (Juve usually jams his hands in his overcoat pockets.) Instead, Feuillade keeps his actors busy with small props. Here, as Fandor writes a story, Juve is brooding on his failure to capture his adversary. Before he’s finished one cigarette he’s already rolling another, and he lights up the new one end to end.

Crucially, theatrical space is geometrically very different from cinematic space, as I’ve argued in several other entries. A shot like this wouldn’t work onstage because spectators sitting to the right or the left would have their sightlines blocked by furniture.

Because the camera slices out a wedge of space in depth, actors can be carefully arranged in dynamically developing compositions that would not be visible on the stage. When the doped-up Valgrand is brought to be questioned by the police officials, we first see him through the rear doorway–a view that wouldn’t be shared by many spectators in a theatre performance.

The dazed actor is questioned, with Juve emerging slowly out of the welter of authorities behind him.

Needless to say, the earliest phases of this shot would be unintelligible on a stage; for most members of the audience, the other actors would block Juve. Recall as well that this was accomplished in an era when directors and cinematographers could not look through the lens to see exactly how the configuration would appear onscreen.

5. Develop an appreciation of complex staging. In a cinema relying on analytical editing, our attention is driven to one item or another through cutting and closer views. By contrast, the director of “tableau cinema,” as this 1910s style is sometimes called, must shift the actors around the sets in ways that call our attention to what’s important at each moment. In the course of the scene, the director must also try to maintain some pictorial harmony on the two-dimensional plane of the screen. Shots are subtly balanced, then unbalanced, then rebalanced, all in the service of story intelligibility.

As we’d expect, depth can play a key role here. Take the simple moment when Lady Beltham’s butler announces the arrival of Nibet, the prison guard whom she bribes. Lady Beltham turns at the sound, rises, and moves to the settee.

As Nibet enters, Lady Beltham returns to her writing desk. This is our old friend the Cross, refreshing the image by having the actors trade placement in the frame.

The same choreography of balancing, unbalancing, and rebalancing can be found when the characters aren’t arranged in depth. The scene of Lady Beltham and Gurn drugging Valgrand plays out laterally. Gurn hides behind a curtain, and our awareness of his presence there colors the whole scene. But because Valgrand will be on the settee, for some while Lady Beltham’s position at her tea table would make an appearance by Gurn compositionally clumsy.

As the drug takes effect, Lady Beltham moves to Valgrand’s side. This gesture of concern unbalances the composition–until Gurn peeps out to rebalance it.

Lady Beltham’s stare at him makes sure we notice his presence. Soon the police arrive to return “Gurn” to his cell.

Again Lady Beltham moves to the right, and again it’s motivated: She wants to make sure the cops have gone. But that movement clears a space for Gurn, i.e. Fantômas, to reveal himself in triumph just as Lady Beltham relaxes in relief.

The synchronization demanded of the actors, in pacing and placement, is considerable, and of course the director has to coordinate everything. Feuillade, directing with shouts and a drillmaster’s whistle, drove his actors through each long-take scene. Turn off the music occasionally and imagine him calling out instructions to them.

These examples, and many others, gainsay David Kalat’s curious claim in the Kino commentary that Feuillade’s work exhibits an “anti-style” that doesn’t present stories “cinematically”–because he doesn’t exploit cutting and changes of camera position.

The camera has been plopped down perfunctorily in front of a set in which the actors meander around within the frame without any sense of composition. In several scenes the actors nonchalantly turn their backs on the audience completely. Only rarely does a shot appear in which the actors seem positioned in front of the camera for any specific pictorial effect. The shots ramble on with hardly any change of point of view until the scene ends and a new one takes its place (Disc 1, 11:54-12:20).

Actually, here and in other works, Feuillade’s staging is quite precise. I doubt that many directors today could block fixed shots as fluidly as he does; sustained, intricate staging in this sense is an almost lost art. Hou Hsiao-hsien, in his films up through Flowers of Shanghai, might be the last great exponent of this technique.

We find the same principles at work in later Fantômas episodes. Some scenes have greater pictorial splendor than the ones I’ve considered; many aficionados believe that the essence of the series is on display in the second installment, Juve contre Fantômas. Certainly it has crazier plot twists. (I got through a whole blog without mentioning Juve’s python-repelling suit, below.)

Granted, it’s hard to study the films as they’re unfolding. That’s partly because Feuillade guides our eye so subtly that we get caught up in the plot. Still, re-viewing can help us spot the fine points. With this DVD set, you have at least five and a half hours of fun before you.

In the lurid tales of Allain and Souvestre, Feuillade found sensational material. He had fine actors. He had luminous prewar Paris as a backdrop. And he had at his fingertips all the resources of tableau cinema. The whole mixture creates a lively cinematic experience. Watching films like Fantômas and Ingeborg Holm and The Mysterious X and many others from 1913, we can still be bowled over by their exquisitely modulated storytelling. If Feuillade is less baroque than Bauer and less poignant than Sjöström, he’s also more brisk, laconic, and playful. Call him the Hawks of the tableau tradition. Thanks to this new release, more Americans will have a chance to enjoy his exuberant creativity.

And they can have all the frissons they want.

Searching “tableau” in our blog entries will offer many further examples of what I’m discussing here. Our 1913 entryoffers an overview of what Feuillade’s contemporaries were up to.

The Kino set includes two other Feuillade films, The Nativity (1910) and The Dwarf (1912). These are better transfers than the main attractions, and make for some interesting comparisons with his artistic strategies in Fantômas. There’s also a short documentary on Feuillade’s career, adapted from the Gaumont box set Le Cinéma premier, which contains many Feuillade titles. Other Feuillade films are available on US DVD: Les Vampires, in an out-of-print Image set; Judex, from Flicker Alley; and various items in the Kino package Gaumont Treasures, 1897-1913. That set, a selection from the Gaumont box, includes The Agonie of Byzance, made the same year as the first installments of Fantômas.

As times changed, Feuillade adopted editing, sometimes in rather flashy forms. For examples, go to my chapter on Feuillade in Figures and here. Essays by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs show how performance style adjusted to the tableau tradition. Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition traces the somewhat differing developments in U. S. cinema of the period.

For all things Fantômas, visit the Fantômas Lives website. There’s also the very helpful Encyclopédie de Fantômas (1981), self-published by the mysterious ALFU. If you want to know the percentage of deaths by defenestration in the oeuvre (6.8 %), this is the book for you. David Kalat offers a wide-ranging survey of Fantômas’ influence on modern art and popular culture in “The Long Arm of Fantômas,” in Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives, ed. Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (MIT Press, 2009), 211-224.

Francis Lacassin has written prolifically on both Fantômas and Feuillade. The arch criminal earns a chapter in Lacassin’s À la recherche de l’empire caché (Julliard, 1991), while his Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des vampires (Bordas, 1995) remains the essential work on the director.

Juve contre Fantômas.

A serial for the unserious

Please silence your mobile phone during the film! Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

DB here, still in Yurrp:

Today the Cinémathèque Française will celebrate Bastille Day by showing one of the strangest movies the programmers could have picked–sort of the Monty Python’s Flying Circus of the 1910s.

Le Pied qui étreint (1916), directed by Jacques Feyder, is a four-part parody of the crime serial. The title translates as “The Clutching Foot,” and as if that weren’t a clear enough signal, Gaumont’s announcement in the trade press set the tone:

A sensational film in 1979 episodes–assembled in four installments without any dull spots.

The running conflict pits the plus-size inventor Clarin, his boy assistant, and his rich girlfriend Eliane against a ruthless, incompetent secret society modeled on Feuillade’s Vampires. The boss of the gang is a mysterious masked figure always wheeled around in a baby carriage with his feet sticking out in front. Gang members recognize each other by flashing an emblem of a bare foot painted on the soles of their shoes.

In the first episode, Clarin invents a wireless telephone, which causes him some embarrassment in movie theatres. Electricity is also on the mind of the Clutching Foot gang, who rewire Eliane’s house so that when she answers the phone she falls into spasms of shocks. Soon all the servants who try to grab her are splayed out on the floor, convulsing in synchronization. Fortunately Clarin and his assistant rescue all by judicious use of rubber gloves.

In “The Black Ray,” the gang devises a gadget that emits a beam that will turn a white person black. The device proves startlingly effective on Eliane, but again Clarin has a scientific solution, sending a current through her to revive her pale beauty. Part three involves the Chinese branch of the The Clutching Foot. They kidnap Eliane and lull her into languor by means of a sinister incense. But Clarin, disguised as a Chinese, rescues her, and his boy displays unexpected pistol skills by dispatching a dozen Chinese while eating a bun.

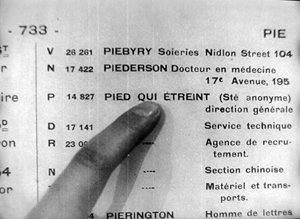

Feyder and his scriptwriters make merciless fun of the still-emerging serial conventions. Masked thugs break into a house, but passing citizens and policemen are completely indifferent. A mysterious message is sent to the heroine via paper airplane, which gets stuck in her hair. When some of the gang converge on Eliane’s parlor, they hide in different crannies and flash their foot-insignia all at once. The apparently unlimited resources of Zigomar and Fantomas are taken to their logical conclusion when the Clutching Foot team boasts of its resources in the city directory.

The iconic image of cops converging on crooks is pushed to a nutty limit.

The last installment is the most peculiar. The master of the Clutching Foot is revealed to be none other than Charlie Chaplin. This shameless effort to cash in on the star’s popularity makes him central to the episode. After a chase through a hotel, Chaplin escapes the cops, worms his way into Eliane’s affections, and winds up marrying her. The wedding feast features a lookalike for the star Max Linder as well as guests from other Gaumont films, including the child star Bout-de-Zan and Marcel Levèsque, a comic fixture in early Feuillade and memorable as the censorious concierge in Le Crime de Mr. Lange. The Charlot imitator is Georges Biscot, discovered by Feyder and soon to play many roles for Feuillade. The woman who slinks around in her leotard and makes with those Irma Vep eyes is Musidora herself. The jokey star walk-on is clearly not unique to our time.

The movie ventures into new territory at the end, when Charlot and Eliane retire to the bridal suite. For once the randy tramp gets some real action.

In a nice closing touch, the hotel staffer who collects shoes for cleaning writes the room number in chalk on Charlie’s boots–a recollection of the high-sign of his gang.

I haven’t mentioned other appeals, such as Chinese gangsters flung off a spinning weather vane, or the moment in the last installment when Clarin’s lad sets up a projector in the lab and, as if willing the whole movie to start over, screens the opening of the serial’s first part. Take that, Postmodernism!

It’s all a bit juvenile, but no harm in that. Sometimes, as Tsui Hark remarks, it’s fun to be stupid. And Le Pied qui étreint should remind us of something important. Too often we assume that parody is a sign that a form or genre is exhausted, that there’s nothing left to do but mock it. But that’s not always so. Parody needn’t announce decline or decadence. Parody is lurking everywhere, ready to spring out as soon as conventions are crystallizing. Irreverence, vulgarity, reflexivity, derangement, and dirty fun are wired into popular cinema from the very start.

For contemporary reactions to the film, which were a little stiff-lipped, see Henri Bousquet, “‘Le pied qui étreint,'” Cahiers de la Cinémathèque no. 40 (1984), 23-24. My quotation from the Gaumont ad is taken from this article. For a brief online comment and a nice production still, go here.

Thanks to Nicola, Francis, and Bruno, who reminded me that Feyder was a Belgian.

Marcel Levèsque, Kitty Hott, Biscot, and Musidora at the wedding feast.

Capellani ritrovato

Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse.

Kristin here–

[Note, July 11, 2011. The release of a considerable number of Capellani films on DVD since the 2010 festival has allowed me to add some frames to my examples below. The frames from L’Arlésienne, L’Épouvante, and Pauvre mère are new, and the one from Cendrillon has been replaced by a better copy. For more on the DVD, see the entry on the second half of the retrospective.]

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, researchers into silent cinema became used to the discovery of little-known auteurs. The 1910s proved an exceptionally rich source of directors beyond the familiar names of Griffith, Ince, Chaplin, Feuillade, Lubitsch, Stiller, and Sjöström.

In 1986 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto’s epic retrospective of pre-1919 Scandinavian cinema revealed the Swedish master Georg af Klercker. In 1989, a similarly ambitious presentation of pre-Revolutionary Russian films brought the work of Evgeni Bauer to light. In 1990, the “Before Caligari” year added Franz Hofer to the list of obscure directors at last receiving their due. After that quick series of revelations, there has been a dearth of such significant revelations until, some would argue, now.

This year Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato presented 24 films directed by Albert Capellani (1874-1931), previously known mainly to specialists for two films, his magisterial adaptations of Hugo in the four-part serial Les Misérables (1912) and of Zola in Germinal (1913). The retrospective has been  arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

A gradual rediscovery

When Georges Sadoul wrote his multi-volume Histoire général du cinéma, the second part (1948) mentioned Capellani a few times. With the lack of available prints of the films, however, he was limited to treating the director primarily as the head of S.C.A.G.L., the prestige production unit launched by Pathé in 1908. Richard Abel’s The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (1994) devotes considerably more space to Capellani. Dick was able to view and analyze seven of the shorts and four features but was hampered by the incompleteness of some of these and the lack of such key films as L’Arlésienne (1908). As Mariann points out in her program notes, Capellani’s significance has been commented on by several scholars, including our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. (Ben’s detailed analysis of the acting in Germinal is here, including a citation to a 1993 article on the film by Michel Marie).

Mariann, however, has recently been instrumental in bringing Capellani’s films to broader attention. The decision to mount retrospectives of his work has spurred archives to restore several which had been unavailable or lost, and more prints will presumably be ready for next year.

Capellani has actually been creeping up on us in Bologna for some time now. In 2006, Mariann’s programs from 100 years ago had reached 1906–the year when Capellani’s career really got started, though at least one of his films appeared in 1905. We saw only one from 1906, La Fille du sonneur. I can’t say that I remember anything about it. In the 1907 program, Les Deux soeurs, Le Pied de mouton, and Amour d’esclave. Again, I probably would have to say that I don’t recall these films, except that I vaguely recognized Le Pied de mouton, a fairy tale about a young man who receives a magic object in the form of a large sheep’s foot, when it was shown again this year.

By 2008, however, a pattern had started to emerge, and Mariann showed seven Capellani films, with six of them forming one program devoted solely to the director’s work, “Albert Capellani and the Politics of Quality”: La Vestale, Mortelle idylle, Corso tragique, Samson, L’Homme aux gants blancs, and Marie Stuart. The seventh, Don Juan, appeared in the “Men of 1908” program.In visiting archives and choosing films Mariann often saw prints without credits and from unknown directors, so the pattern only gradually became clear. In the 2008 catalogue she reflected on her realization that Capellani was showing up regularly in her choices for the annual centennial celebrations: “When organising the 1907 programme, however, in the light of Amour d’esclave, a gorgeous mise-en-scène of classical antiquity, I asked myself for the first time, ‘Who made this sophisticated film?'”

She speculated that the relative neglect of Capellani perhaps came from the Surrealists’ campaign against highbrow filmmaking during the 1910s and 1920s:

From his very first film on–the memorable Le chemineau of 1905, based on an episode from Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables–Albert Capellani transports the contents and qualities of bourgeois culture to the cinema. He films Zola, Hugo and Daudet–his Arlésienne of 1908 has unfortunately been lost. His many fairy tale films (scène des contes), biblical and historical scenes reveal him as a great art director, who also adopted the latest developments in modern dance and worked with its stars Stacia Napierkowska and Mistinguiette. Highly versatile, he had an unerring sense of the best approach to a given genre.

Fortunately, L’Arlésienne has subsequently been discovered by Lobster Films, just in time to be presented this year.

The 2009 program contained only two Capellani films, but one was the extraordinary Zola adaptation L’Assommoir. This had been known only from fragments until a complete copy was found in Belgium. It displays an unusual degree of realism that fits the naturalist subject matter and also contains complex and deft staging that moves numerous characters around a scene in a way that shifts the spectator’s attention among them exactly as the flow of the narrative requires. The other, La Mort du Duc d’Enghien, was shown again this year. It’s a rare case of an historical drama of the period that manages to arouse a genuine sympathy for its main character, a young nobleman unjustly arrested and executed upon Napoleon Bonaparte’s orders. More on it later. The 2009 catalogue announced that in the following year, Capellani would graduate from the annual “Cento anni fa” programs to his own retrospective.

This year’s films

This first full-fledged Capellani retrospective gave a generous though not complete overview of his surviving films from early 1906 to 1914—a few bearing 2010 restoration dates. Capellani also worked in the United States from 1915 to 1922, and the program included The Red Lantern, a 1919 feature starring Nazimova. This, Mariann’s notes assure us, is “a taster for next year’s festival,” which will include further restorations from the French period, as well as more features from his American career. (It would be good to see the other Capellani films shown in previous years repeated, now that we have a sense of his work more generally.)

Ideally our examples here should include frames from the films shown at this year’s festival, but none of them is out on DVD. The Brewster article linked above has a generous selection of well-reproduced frames from a 35mm print of Germinal. As far as I know, the only Capellani film available on DVD is Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, on the third volume of Kino International’s “The Movies Begin” set. I’m sure it was included there not because it was a Capellani but because it survives in beautiful condition and is an epic with elaborate hand-coloring. I’ve included frames at the top and bottom of this entry, despite the fact that it has not been shown at Bologna. The smaller frames illustrating a few of films shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato come from the Gaumont Pathé Archives website (registration required). This site is the best online source of information on the director’s films, including complete video versions in a few cases. These are, however, quite small screens, and they display the double branding of a prominent timer and a bug of a Pathé rooster superimposed over much of the frame.

Capellani had worked in the theater as a director and actor until Pathé recruited him in 1905. In a sense, he became a specialist in literary adaptations, especially after his appointment in 1908 as artistic director of S.C.A.G.L. Yet the films being shown this year include pure melodrama (such as Pauvre mère, “Poor mother,” 1906), crime-suspense films (L’Épouvante, “The Terror,” 1911), classic fairy-tales (Cendrillon, 1907), and historical/biblical costume pictures (Samson, 1908).

With his theatrical background, it is not surprising that Capellani was able to cast many old colleagues in his films, notably Henry Krauss, who played Quasimodo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1911) and Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (1912). Wherever his actors came from, however, Capellani was a master at directing performances. In many cases the acting makes characters who would seem completely conventional figures in most films of the day into people with whom the audience can empathize.

The staging in Capellani’s shots is inevitably impeccable. The progression of the story is clear even in shots with numerous characters on camera. More of his stage experience coming out, one might say, but he also adapts his technique to the visual pyramid of space tapering toward the camera’s lens.

L’Évadé des Tuileries (1910), for example, deals with the Count du Champcenetz, the governor of the Tuileries during the French Revolution, who initially tries to alert the royal family to their impending arrest and subsequently flees for his life from the revolutionary forces that invade the palace. In the most spectacular shot, he rushes in, exhausted and wounded, to speak to the king as the members of the royal family gradually enter and guards surround them. Champcenetz collapses and slides partway under a chair at the foreground right as the revolutionaries burst into the room. The business of the ensuing struggle, the departure of the combatants with the royals under arrest, and a short burst of looting leaves a still scene with the dead and wounded on the floor. Suddenly an arm moves at the far lower right corner of the frame, and we become aware that Champcenetz has survived.

David has praised the sustained tableau staging in depth of the 1910s, in the films of Feuillade, Sjöström, Hofer, and others, but here is Capellani doing it all in 1910—and this is not the first of his films to display such control of the complex arrangement of actors in space.

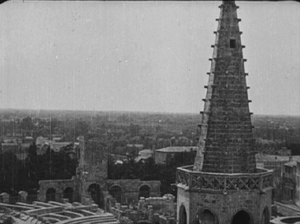

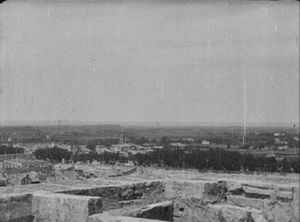

None of this is to suggest that Capellani’s films are “stagey.” He is quite capable of a cinematic flourish for purposes of dramatic effectiveness. L’Arlésienne, shot largely on location in the old town of Arles, includes a shot of the young couple atop a tower that looks over the cityscape. The camera begins on the spire, panning right until the couple appear in medium shot, with the town beyond them and the parapet. They wander out right, and the camera pans around the parapet, only catching up with the couple when they are roughly 180 degrees opposite to where the camera started:

It is hard to believe that in London L’Arlésienne played on the same program as L’assassinat du Duc de Guise, which, sophisticated as it is in some ways, seems seems downright old-fashioned when contrasted with Capellani’s film.

Even flashier is L’Épouvante, which seems at first a simple story of a young woman in danger as she retires for the night, unaware that a burglar had stolen her jewelry just before she came in and is now hiding under the bed. She lights a cigarette and carelessly tosses the match on the floor. The camera tracks slowly back from the bed to bring the burglar into view; he registers fear that the match is still alight and might set the rug on fire. He reaches to snuff it out, and a sudden cut places us at a high angle above the heroine as she looks down and sees the hand appearing from beneath her bed. A return to the long shot displays her reaction:

Up to this point our sympathy has been entirely with the heroine. But once she escapes the room and locks the burglar in, his struggle to escape before the police find him takes up much of the remaining action and gradually gains him our sympathy as well. Trapped multiple stories up, he climbs to the roof, only to have to retreat as the pursuers rush up and search there. Moving downward, the burglar ends up hanging by an ominously bending gutter.

Only the heroine is left in her flat to discover his plight, and she lowers some drapes for him to climb up. In a touchingly awkward scene, the man is relieved but unable to express his gratitude except by returning the stolen jewelry and silently exiting, while she makes no attempt to stop him. In a way, L’Épouvante reminded us of Suspense, Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley’s remarkable 1913 film of a woman besieged in her house by a burglar, but the unexpected shift of emotional dynamics between the two characters in Capelanni’s film makes it equally memorable.

Capellani’s pictorial sense in real locations has been widely remarked upon. Even in La Mariée du château maudit (1910), a relatively slight tale of spooky doings in a deserted castle where a wedding party plays hide-and-seek, becomes impressive in part because of its use of an extensive set of actual ruins. There’s also a remarkable moment after the bride accidentally becomes locked in a room with a skeleton dressed in a bridal gown. She reads an old book telling of the young woman’s fate, and two successive bits of the story appear as matte shots on the right and left leaves of the open book. (Working at Pathé, Capellani could use impressive special effects, as the dream image in the Aladin frame at the top demonstrates.)

The sets are masterful as well. I was particularly struck by Jean Valjean’s desk in the second episode of Les Misérables (1912). It creates an effect of forced perspective that is like German Expressionist eight years ahead of its time. Valjean has escaped from prison and become a mayor and successful small-factory owner. Javert, formerly a guard at the prison and now a local police officer, suspects Valjean of being the fugitive. Now he comes to Valjean’s office to introduce himself.

Valjean sits at the left behind an enormous desk which dominates the left and center of the screen; its size is exaggerated by rows and stacks of thick volumes ranged across its top. About a third of the screen is empty at the right, where Javert enters at the rear and walks only partway forward. The effect is to make Javert appear smaller than he really is, with the low camera height that Pathé films were using by this point exaggerating the effect; during part of the scene he is also partially blocked by the desk. The suggestion is that he has no ability to follow up his suspicions of such a powerful man.

In a subsequent scene, when Valjean brings the ailing worker Fantine to his office, the desk has been moved away from the camera, which frames the scene from further to the right. The result is a far more open space at the right, while Valjean brings forward a chair for Fantine that puts her in front of the desk. Unlike Javert, she is not dwarfed by the desk, which, once Valjean comes to lean over her, is barely visible. Instead, the right half of the screen is left unoccupied so that a flashback can fill it.

In the scene like the one with Javert, a German Expressionist film would have exaggerated the size of the desk even further and perhaps tilted the floor up at the rear, but the effect is clear and dramatic enough as it is. Again, it is not an effect one would expect to find in a film of the early 1910s. There is also a contrast between the massive desk and the relatively small, insubstantial table that Javert uses as a desk in the setting of the police headquarters

Even the most conventional films receive what I began to recognize as Capellani touches, often to bring a moment of realism into a fantasy or melodramatic setting. In Cendrillon, the gardener who carries in a huge pumpkin to be turned into the heroine’s magic coach exits wiping the sweat from his head with a handkerchief (below left). The little girl who falls out of a window to her death in Pauvre mère leaves a large, dramatic splotch of blood on the sidewalk when her lifeless body is lifted—a realistically gory touch of a sort which I don’t recall seeing in any other film of this era (below right). When the hero finds the magic lamp in Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, he blows dust off it and turns it over to shake out further dirt (see bottom).

Another sort of touch appears in La Mort du Duc D’Enghien, a carefully executed motif of a sort one doesn’t often see in films of this type. The hero is arrested while at a hunting lodge, and throughout he wears a distinctive hat that’s probably part of a hunting outfit. He throws it defiantly to the floor during the courtroom scene in which he is unjustly condemned; he throws it down again in his cell, this time to indicate despair and exhaustion; in the final execution scene, he tosses it aside as part of his brave resignation, facing the firing squad with open arms and without a blindfold. These moments aren’t stressed, and one could understand the plot perfectly well without noticing the repetition. Still, the motif helps characterize D’Enghien quickly in this relatively short film and indicates the care with which Capellani was crafting even his one-reelers.

Mariann was somewhat apologetic about La Glu, a 1913 feature, since it centers around a femme fatale who victimizes three men in the course of the narrative. The title is the heroine’s nickname, and it means what it sounds like, “glue,” and particularly sticky substances like bird-lime that are used to ensnare. But the audience thoroughly enjoyed this distinctly absurd but entertaining and fast-paced tale of a heartless, mercenary woman, played with relish by Mistinguett, and the men foolish enough to fall for her. After all, there are plenty of depictions of love-’em-and-leave-’em men from this period, so why not turn the tables? At least one flagrant coincidence brings all of them to the south of France, where the heroine goes for a vacation, and Capellani contrasts the early scenes of high-society Paris with the stark seascapes in and around a fishing village. Though another literary adaptation (from a novel and play by Jean Richepin), this film certainly stands out among the pre-war features and demonstrates once more Capellani’s versatile ability with a range of genres.

After all these treats, the last French feature on offer, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914), proved a slight let-down. Capellani had a penchant for substituting letters and other texts for intertitles, but this film pushes the device to the point where sometimes it seemed as if every other shot was an insert. The plot, dealing with a scheme to rescue the imprisoned Marie Antoinette, was also frustratingly complicated and not presented with the admirable clarity that characterizes most of the other films. As I’ve mentioned, Capellani was often able to generate an empathy with the characters which is rare for films of this period, but as a result of the constant plot twists, the Chevalier and his endangered mistress remain rather remote figures. There are some effective moments, though. One exterior view of the protagonist’s home places a door at the upper center, approached by a symmetrical pair of staircases running to the right and left and forming a pyramid shape. A foreground pond elaborates the space still further, so that when a crowd tries to break in, the staging utilizes the frame vertically and horizontally, with intricate movements of individuals to avoid the water.

Ahead of his time–up to a point

As I remarked in an entry on last year’s festival, L’assommoir struck me as looking like it had been made in 1912 or 1913 rather than 1909. Now it becomes clear that many of Capellani’s films give this sense of trying things that other filmmakers would begin doing routinely a few years later. In some cases, like L’Arlésienne, it’s a focus on acting of a sort that we associate with Griffith’s films like The Mothering Heart or The Painted Lady. In others, it’s the motifs or the subtle changes of framing or the eye for landscapes. Although the editing is not usually flashy, Capellani is good at keeping spatial relationships clear, as the series of shots depicting Valjean’s escape from prison in the first part of Les misérables demonstrates. As Mariann wrote, he seemed able to adapt to any genre. I’m not a particular fan of the historical films so common during this period, but Capellani manages to humanize most of his.

It was only with Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge that the sense of Capellani being ahead of most of the directors of his time largely disappeared, though it seems premature to judge from a single 1914 film. Perhaps during the immediate pre-war era, and especially the creatively fecund year of 1913, the exploration of the cinema by an increasing number of masters created a spurt that he did not participate in. And perhaps more films from 1913 and 1914 will appear in next year’s retrospective and give us a better sense of how his career developed in that crucial period. It will also be interesting to trace his assimilation of the developing classical Hollywood norms once he moved to the U.S. By 1919 and The Red Lantern, he clearly had absorbed the norms thoroughly, and his style had become indistinguishable from that of his American colleagues.

Added July 13: Roland-François Lack has kindly written to point out that another Capellani film exists on DVD. (Thanks, Roland-François!) His 1908 version of the French tale Peau d’âne was included as a supplement on the  collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

The source of the print isn’t clear on the disc. (It’s another one that hasn’t been shown at Bologna.) Probably Pathé’s own archive, since there’s a little rooster-shaped bug superimposed at the lower left in every shot.

It’s a fairly contrasty print with replaced intertitles in French only. It also seems to be running at 24 fps or something close to it. The action zips right along, which is a pity. There’s a lot of carefully executed pantomime-style acting. It’s impossible to catch all the gestures, especially since there are often three or four actors going at it at the same time. It would actually be a good film for teaching about the acting styles of this period if one could just slow it down.

I wouldn’t have spotted this as a Capellani film if I hadn’t known its source when I watched it. Still, it has some of the traits we’ve recently come to associate with him. The meeting between the heroine and Prince Charming takes place in a carefully chosen setting with a reflecting pond in the foreground. It looks like the film was shot on a hazy day, but it looks as though the camera may be set up to shoot with the sunlight at the characters’ backs.

The film also has the director’s typical elaborate interior sets juxtaposed with a dramatic use of real exteriors. The frame at the left below shows the fairy appearing for the first time to the princess. It’s not easy to see, but the busy interior includes a deep, diagonal space with several arches decorated with portraits that are painted, frames and all on the square pillars. Once the heroine disguises herself and flees to avoid her suitors, Capellani goes on location, using an impressive château and streets that look like they are in the same vicinity.

I hope that some of the more realistic films will soon appear on DVD. Lobster in particular could make their newly restored L’Arlésienne available.