Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

More cinema Bolognese

Josette Andriot, decked out for Protéa.

Kristin here, with more from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna:

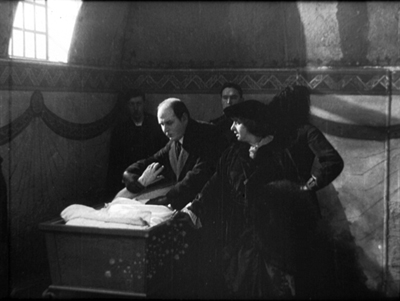

When one thinks of female masters of disguise and action in the silent cinema, Musidora as Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampyrs probably springs first to mind. But for the historian, hovering always in the background was the legendary film by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, Protéa (1913), with Josette Andriot in the lead role. We knew the film mainly from a frequently reproduced image of the heroine in a black outfit, one of many she wears in the film.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Protéa has now been restored, though there is still missing footage. The heroine’s partner is Lucien Bataille, looking rather like a particularly devious James Cagney in the role of L’Anguille (“The Eel”), whose quick-change abilities and athleticism match hers. The thin, episodic plot revolves around a classic Macguffin, a treaty between two imaginary, vaguely Eastern European countries. The pair must acquire the document and hold onto it through one danger after another, outnumbered and chased all the while by a ruthless gang of spies for the other side.

I was startled by how modern the film seemed. Critics today tend to claim, inaccurately, that big action films throw some big thrill at the audience every few minutes. Protéa really does. The underlying purpose of the plot is to have the two leads escape from one sticky situation and change disguises, only to land immediately in another sticky situation. It’s essentially a serial boiled down into a feature.

The term “cinema of attractions” was originally coined by Tom Gunning to describe very early films that depended on novelties rather than narratives. These days, many academics apply the phrase to almost any film, old or new, boasting a lot of action and big special effects. But I’m tempted to use it of Protéa anyway. Jasset usually doesn’t keep Protéa and L’Anguille in any one disguise or situation long enough to exploit the initial premise. One moment she’s pretending to be a man; next thing we know, she’s an elegant partygoer and L’Anguille is a servant. The basic problem is that whenever the characters get into trouble, they don’t rise to the occasion by exploiting their current roles more cleverly. They just flee and assume a new disguise to try again. As a result most of the individual episodes remain unmemorable.

One exception is a sustained sequence showing the couple as traveling animal trainers. At one point they crawl into the cage and play with a real lion, and they stay in these disguises long enough to actually use the big cats to fend off their pursuers. The final hectic chase, with Protéa on a bicycle fleeing toward a bridge set aflame by the villains, is the most impressive passage we can enjoy as sustained action. (I won’t reveal how it comes out, except to say that the climactic moment prefigures a modern action heroine driving a bus toward a gap in an unfinished freeway.)

Protéa is fun, in large part due to the talent of the two leads. It’s a pity that this was Jasset’s penultimate film. He died in hospital before it was released. (His last film, La Danseuse de Kali, also starring Andriot, was recently rediscovered by our friend Hiroshi Komatsu and was shown in this year’s festival.) Perhaps Jasset would have developed into one of the major directors of serials. Still, one can see why Feuillade, who knew how to build suspense by stretching out a scene’s action, became the French master of the form.

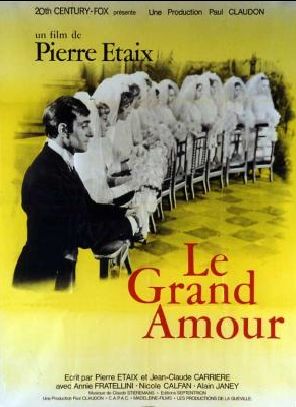

Etaix Refurbished

In an earlier entry, I mentioned that for some years French comic director and actor Pierre Etaix had not controlled the rights to his own films (two shorts and six fiction features). During that time, they were out of circulation and unavailable in any format. That situation has finally been rectified. Etaix has recovered the rights, and all the films have now been restored. They were re-premiered earlier this year at Cannes, and two were included in Il Cinema Ritrovato: the short Heureux anniversaire (1962) and the feature Le grand amour (1969).

Etaix’s early work in the cinema was during the 1950s as an assistant to Jacques Tati, and he is widely seen as having been greatly influenced by Tati. That’s true to some degree. In Le grand amour there are gags using sudden peculiar noises. Although the plot centers around the hero Pierre, his wife Florence, and his in-laws, there are nosy neighbors and waiters through whose eyes we are occasionally asked to view the action. When Pierre’s friend gives him instructions on how to behave on an upcoming date with his pretty secretary, bar patrons assume that they’re witnessing two gay men flirting.

Still, Etaix’s general approach is not particularly Tatian. He does not play a continuing character from film to film. In Le grand amour, as the young husband lured into managing his father-in-law’s factory, he dresses in conservative suits and casual wear; no Hush Puppies, striped socks, and too-short raincoat for him. Pierre succeeds in his dull job, unlike Hulot, who makes a mess of things when given a low-level job at his brother-in-law’s factory. The neighbors watch Pierre not because he is eccentric, but because they jump to wrong conclusions about his mundane behavior.

More importantly, though, Le grand amour creates a great deal of its humor with a technique that Tati would never use. He frequently shows hypothetical alternatives to the scene at hand. What if Pierre’s sophisticated friend were married to Florence? We see a scene played out with the friend in his place. There is a dream in which Pierre’s bed drives like a car along a country road, encountering other bed-cars and finally picking up the new secretary, hitchhiking by the road. When Pierre finally dares to take the secretary out to dinner, he launches into a nervous, boring monologue on business prospects, and we see him as she does, successively older and grayer with each reverse shot. When the gossipy neighbors pass along a story about Pierre, we see the successively exaggerated versions played out one by one, from the reality in which he merely tips his hat to a pretty woman he passes in a park through overt flirting to a passionate encounter behind a bush.

Le grand amour is not as funny as Tati’s films, but that probably results from an explicit melancholy that underlies this tale of disillusionment with marriage and final acceptance of the realities of life-long love. At times it reminded me more of the playful moments in Truffaut, especially in Shoot the Piano Player. Whether or not one wants to place Etaix in the New Wave, his play between reality and fantasy would seem to put him in the category of “ludic modernism” that Malcolm Turvey spoke about in his paper at the recent Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image conference.

The restored print was beautiful, with the kinds of bright and pastel colors and high-key lighting that one seldom sees in the drab films of today. Presumably the new copies will show at other festivals and in art-houses with DVD releases to come.

Cinephiles’ corner

Bologna brings out a bevy of critics, historians, programmers, and unabashed film lovers of all stripes. Herewith, a sampling from DB.

Two critics for the ages: Kent Jones of Physical Evidence and the World Cinema Foundation, alongside Joe McBride, author of books on Ford, Capra, Welles, and Spielberg.

Dick Abel and Virginia Wright Wexman, both distinguished scholars, flank a copy of Dick’s book, French Cinema: The First Wave–presumably kept under glass like the rare specimen it is.

Curatorial cuddling: Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, Adrienne Mancia retired from MoMA (and once a UW Badger).

The Cottafavi Cult invictus: Critics and programmers Barbara Wurm, Olaf Möller, and Christoph Uber, always in the front row.

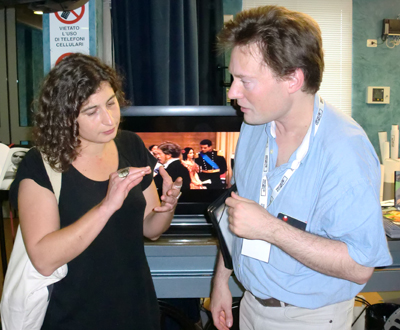

Camille Blot-Wellens, director of Film Collections at the Cinémathèque Française tells Danish historian Casper Tybjerg of her restoration of Albert Capellani’s Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914).

Two walking film encyclopedias sitting down: Kevin Brownlow, pioneer British historian, director, and collector, and Lee Tsiantis of Turner Classic Movies.

David Meeker, master of British cinema and jazz on the screen; Matthew Bernstein, author of Walter Wanger, a study of the Leo Frank lynching, and other studies of film history and culture.

Mariann Lewinsky, heroic programmer of the 1910 series and the Capellani retrospective, introduces Nikolaus Wostry, of Filmarchiv Austria.

More to come in at least one more Bologna-based entry!

John Ford, silent man

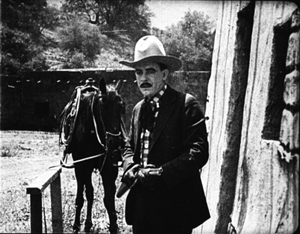

John Ford on the set of Air Mail (1932).

DB here:

This is the busiest installment of Cinema Ritrovato I can recall. We scarcely have time to sleep, let alone blog. The coordinators Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée have outdone themselves in offering something for everybody, from early films to postwar French and Italian rarities up through a tribute to Stanley Donen and special screenings of The Leopard and Metropolis. Our attention has been riveted by the 1910 programs and an extensive collection of films directed by Alberto Capellani, a little-known master of silent film.

One headliner is the early Ford series: all his surviving silents, plus a selection of rarely-seen talkies. The first one screened, The Black Watch (1929), concentrates on intrigue in the Khyber Pass during World War I. Captain King is assigned to India while the rest of his Scots regiment is sent to Europe. In India, King masterminds the defeat of the forces of Yasmani, a woman who has been taken as sort of a goddess by her followers. The central section, involving Yasmani’s passion for King and his betrayal of her, seems to me sketchy and rushed; Ford’s real interest, not surprisingly, is in the rites of comradeship among the Black Watch. Twenty-two of the film’s 91 minutes are taken up with the opening dinner celebrating the regiment, conducted while King gets his assignment. Since his mission is secret, he abandons his comrades and suffers their opprobrium. A bookended sequence at the close shows him returning to the Watch as, in the trenches of war, they hold another dinner, complete with ruffles and flourishes.

Some of the central portion was directed by Lumsden Hare, but it too has some striking moments, perhaps most memorably the display of Yasmani’s powers when she conjures up an eerie vision of the European battlefield in a glowing crystal ball. The war sequences have the dank Expressionist look that Murnau brought to Fox and that Ford exploited in Four Sons (1928). There are as well touching train-station farewells between brothers and between father and daughter, all of which seem very Fordian. Overall, Ford finds ways to avoid the multiple-camera shooting common to early talkies, often using offscreen dialogue during reaction shots.

Also fairly free of multicamera work was The Brat (1931). Like many talkies derived from a creaky Broadway play, it entices us with a “cinematic” curtain-opener. Cops (including the young Ward Bond) hustle perps into night court, all captured in a flurry of high and low angles, bursts of deep space, and swift tracking shots. Afterwards things slow down, enlivened by some social satire (the pretentious novelist writes with a quill pen), a few sight gags (an artist’s muscled model who discovers he’s been rendered in a faux-Cubist image) and an all-in grappling fight between a society dame and a girl from the other side of the tracks. According to Ford, the fight got its impact from the fact that the actresses couldn’t stand each other.

The first silent Fords were introduced by Joe McBride. “When the real West ended,” Joe remarked, “the cinematic West began.” Born soon after the closing of the frontier, Ford was fascinated by cowboys and Native Americans. Early filmmakers were to a surprising extent celebrating the stoic Indians uprooted and forced to give up their way of life, and this resonated with Ford. The elegiac quality we find in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and other late films, Joe suggested, was already there in the genre. Ford’s own first Westerns, thanks partly to the presence of Harry Carey, carry an air of resignation to history. Even the fragmentary sequences surviving from The Secret Man (1917), in which Harry must sacrifice his freedom to save a little girl, have a severe melancholy.

Hell Bent (1920) has long been famed for its flashy, unrepeatable shot: A carriage pulled by horses tumbles into a ravine; the camera tilts down to follow the crash; and then the horses, freed at the top, come hurtling back into the frame to pass the wreckage. Otherwise the film is consistently agreeable, suffused with Fordian camaraderie among drunks and respect between hero and villain. This last element is starkly dramatized when Harry and his adversary, having wounded each other in a gun duel, must crawl through the desert together.

On my first viewing, I didn’t see in Hell Bent the inventiveness and grace notes I admire so much in Ford’s first feature, Straight Shooting (1917). As we’ve mentioned before, this film shows a mastery of the classical Hollywood style that emerged in the late 1910s. It bears comparison with William S. Hart films of the period, high points of filmmaking craft. Late in the plot Ford give us a shootout with ever-tighter framings that could have come out of Leone.

Whether Ford invented this particular piece of cinematic rhetoric we can’t say; too many silent films are lost. But coming from a 23-year-old filmmaker in his first feature, this remains a remarkably assured use of the continuity editing system for 1917.

Ford’s debt to Griffith has often been noted, and in this movie it turns up in unexpected ways. At one point Joan tenderly puts away the plate her dead brother had used, as if to preserve it. Later, Ford recalls the gesture when the cabin is under siege and bullets blow apart other plates on the sideboard. But Ford has already quietly suggested an association between brother Ted and Cheyenne Harry; as Joan kisses the plate before putting it away, Ford cuts to Harry outside, and then back to Joan slipping the plate into a drawer. Using the then-current technique of a “ruminative cut”, the editing suggests that Joan may also be thinking of Harry, and he of her. The idea of Harry replacing Ted is made explicit at the end when Sims plaintively asks Harry, “You be my son.”

The Griffith influence is particularly acute in Straight Shooting’s climax, when the farmers are under siege in the Sims cabin. Horsemen gallop around the cabin as hired gunmen pepper it with bullets. Meanwhile, Cheyenne Harry has persuaded Black-Eyed Pete’s gang of outlaws to rescue the settlers, and Ford gives us a rousing passage of rapid crosscutting. It’s a canonical last-minute rescue, straight out of the climax of The Birth of a Nation (191t5).

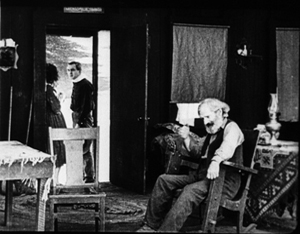

Or more particularly, I think, out of The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1914). Griffith commonly staged interior scenes with doors at the left and right of the frame, letting actors play laterally. The strategy can be considered somewhat theatrical, in that we never see the “fourth wall” that would in reality enclose the characters.

But this leads to problems when you want to show your characters surrounded. In Elderbush Gulch, the settlers are besieged by encircling Indians. At one point, Griffith cuts from the exterior of the cabin to the interior, and to convey the sense of enclosure he has one of the settlers firing “through” the fourth wall, as if over the heads of the audience!

This is an awkward compromise, but at least give Griffith credit for grasping that his dollhouse playing area doesn’t fully render a realistic space. In Straight Shooting Ford provides a more three-dimensional rendering of interiors. Even though most scene in the Sims cabin lacks Griffith’s side walls, the set yields layers of depth, and the famous door in the back of the set opens on to the porch and the farm outside.

During the gunmen’s siege, we get a strong sense of enclosing space by virtue of the cuts of men firing from different angles. In addition, the cabin interior displays a little more angular depth.

But even Ford can’t escape compromises. We never see the space “behind us” in the Sims’ cabin, and as the farmers take up positions at windows, Ford shows us old Sims readying to fire by turning toward the camera and, like Griffith’s settler, aiming through the fourth wall.

The two shots of Sims in this posture go by fast, and they’re less noticeable because the siege hasn’t quite begun. Still, the anomaly indicates that in this setting Hollywood technique still doesn’t give the sense of a wraparound space that we get in the exterior scenes, like the shootout. A few years after Straight Shooting, American directors would master the ability to build up a four-walled interior through careful cutting. Those techniques would then be exploited for dramatic effect, as in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

More to come, but now I must rush off to a morning of early film! If you’re hungry for more in the meantime, visit our category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato for highlights of earlier years.

Dreyer re-reconsidered

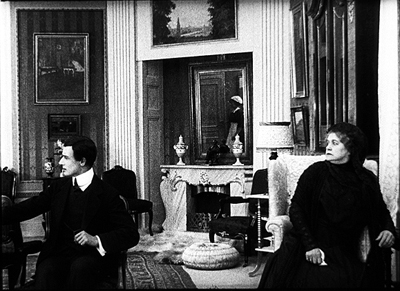

The President (1920).

DB here:

I was late to the feast, but my contribution to the Dreyer site is now up, thanks to Lisbeth Richter Larsen‘s quick work. You can read it here.

Danish cinema was the first national cinema I studied, and Dreyer was my point of entry. I went to Copenhagen in 1970 to see his films for a little book I wrote in the Movie/ Studio Vista series. The manuscript was finished but never published because the series ceased. Good thing for me. I’d be embarrassed today if that book was still floating out there.

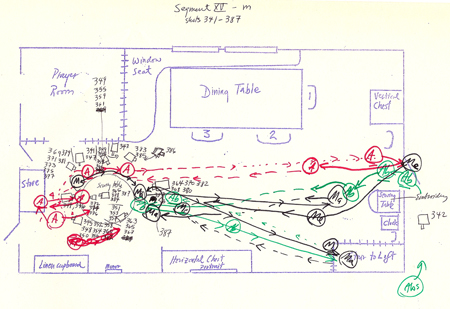

Kristin and I went back to Copenhagen in 1976 to re-watch the Dreyer oeuvre, and I saw the films with new eyes. I had learned a lot more about film analysis and film history, so I was able to see different things in his movies. Now obsessed with how films construct space and time, I drew up elaborate and clumsy plans of actor blocking, camera setups, and camera movements.

What? You don’t recognize this as a string of shots from Day of Wrath? I even notated actor movements offscreen (with dotted lines).

The result of all this fussbudgetry was a 1981 book on Dreyer. I think that some of the ideas there still hold up. But as I learned more about film history in the 1990s, I came to believe that some of my conclusions were off-base.

In particular, my treatment of Gertrud as a radical, deliberately “empty” film seemed tenuous. Influenced by minimalist cinema of the 1970s, especially that of Straub and Huillet (huge admirers of Dreyer), I pushed the case that at the end of his life Dreyer dared to make a movie that was by all ordinary standards simply boring.

Steadier heads tried to talk me out of it, but I clung to the idea. What can I say? I was young and stubborn.

As I studied more cinema of the 1910s, I began to see Dreyer’s career, and particularly his silent films, as tied in complicated ways to other films of that period–not least Danish cinema. For, as I’ve sketched here, Danish cinema of the 1910s was one of the richest traditions of “tableau” staging in Europe. I was able to put my ideas about the Danes’ achievements into clearer form in the last chapter of On the History of Film Style and in an invited essay on the Nordisk company published in a collection at the Danish Film Institute.

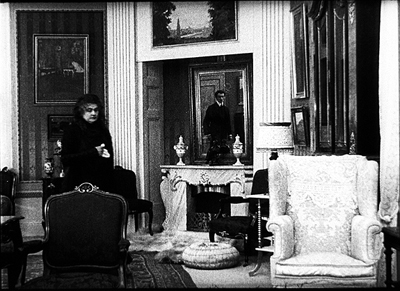

Like their peers in other countries, the Danes often stuffed their shots with furniture and props, in a riot of patterns and textures. Here is an example from Den Frelsende Film (The Woman Tempted Me, 1916). It survives only in fragments, but those fragments are in fine shape.

In addition, the Danes developed elaborate lighting patterns and complex, somewhat Gothic special effects. You can see these options in Ekspressens Mysterium (Alone with the Devil, 1914) and Doktor Voluntas (1915).

Above all there was the intricate staging in depth, often using mirrors. Here’s a seldom-seen example. In Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (Under the Lighthouse Beam, 1913), the father has died, and his wife and son meet in the parlor. A mirror catches them entering, in phases.

The mirror shows Hugo entering the room by moving straight and forward, but when he gets into the shot he comes in somewhat diagonally from the left.

After a moment of sitting in silence, mother and son turn as a maid enters. They look off left, but because we’ve seen Hugo enter in the mirror, we look to the center and see her reflection as she shuts the door.

The maid brings the widow a letter from her other son, Robert. Hugo, fretful, departs and in the mirror we see him look back at his mother.

Or does he? The angle of his glance makes sense compositionally: In reflection Hugo seems to be meeting his mother’s eyes, left to right. But in my first frame, he advanced into the room by looking straight ahead. If he looked straight into the room again now, he’d be looking more or less at us, not at his mother. So I suspect that in my last frame, the actor is actually not looking directly at the actress but off at an angle. He has been directed to this position to allow the mirror to create an artificial, but highly readable, image.

The novice Dreyer, I realized, didn’t indulge in such tableau trickery. His first two films, The President (made in 1918) and Leaves from Satan’s Book (made in 1919), are quite different from the norms that ruled his local cinema. By the time he came to directing, he was more oriented toward analytical editing and fairly flat staging than were the old guard. In this regard he was closer to a younger group of filmmakers emerging at the same time in other countries: Gance, Lang, Murnau, Joe May, and many others, along with Americans like Ford, Walsh, et al. So my newest take is that Dreyer is part of a generation of directors moving toward an editing-driven cinema and away from the tableau style. This idea in turn helped me see Gertrud in a more convincing light.

If you want the argument in full, you can check it on the Dreyer site. The lesson for me is twofold. (A) Dreyer is inexhaustible. (B) The more you learn about cinema (and about life), the more you can see in films that you think you have already understood.

The only book in English surveying the cinema of Dreyer’s elders is Ron Mottram’s indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1988). It doesn’t consider the dual traditions of staging and editing, but it offers a very thorough history of studios, directors, and genres, and mentions some stylistic patterns. The article I referred to is “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” in Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, eds., 100 Years of Nordisk Film (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2006), 80-95. This gorgeous book can be ordered from the DFI shop;I’ll be adding my essay here some time this summer.

For more on the tableau tradition, go to other blog entries here and here and here and here. On the emergence of continuity editing, chiefly in the US, try here and here and here. More detailed treatments are in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, On the History of Film Style, and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

I’m grateful as ever to Marguerite Engberg, Dan Nissen, Thomas Christensen, and Mikael Brae for their help in my research on Danish silent film.

PS 16 June: Jonathan Rosenbaum has republished on his site his detailed and engrossing 1985 study of Gertrud, which includes discussion of the play from which Dreyer adapted his film. Thanks to Jonathan for making his essay available.

The President (1920).

DER GOLEM: Revisiting a classic

Kristin here:

In 2009, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent-film festival held each year in Pordenone, Italy, launched a new series. “Il canone rivisitato/The Canon Revisited” addressed the fact that many rare and often obscure silent films are made available through restoration each year, and yet many young enthusiasts who have started attending the festival have seldom had the chance to see the classics on the big screen with musical accompaniment. The opening group of films proved highly successful, and “Il canone rivisitato 2” will be presented this year, when Il Giornate will run October 2 to 9.

Part of the point of the series is to have historians re-evaluate these classics and examine how well they live up to their status as part of the film canon. Last year I contributed a program note on Paul Wegener and Karl Boese’s 1920 German Expressionist film Der Golem. This year I’ve written about Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s 1916 thriller Hævnens Nat (Night of Revenge, released in the U.S. in 1917 as Blind Justice), which will be shown this year, and rightly so.

When I went back and reread my Golem notes to remind myself what sort of coverage is needed, I decided that the text I wrote then might be of wider interest to those who weren’t at the festival last year. Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai, one of the festival’s founders and organizers, for permission to revise my brief essay as a blog entry. I’ve changed it minimally and taken the opportunity to add illustrations. Here’s what I said at the time:

Der Golem is a classic film—doubly so.

First, it has long nestled comfortably within the list of titles that make up the German Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Teachers of survey history courses are more likely to show Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (which premiered in early 1920) but a serious enthusiast will make it a point to see Der Golem (which appeared later the same year) as well.

From the start, reviewers recognized Der Golem as Expressionist. In 1921 the New York Times’ critic wrote, “Resembling somewhat the curious constructions of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, the settings may be called expressionistic, but to the common man they are best described as expressive, for it is their eloquence that characterizes them” (George Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness, p. 362). In 1930, Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the most ambitious world history of cinema in English to date, appeared. Highly influential in establishing the canon of classics, Rotha adored Weimar cinema, including Der Golem.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art obtained a large number of notable European films. The core collection of the young archive contained such prestigious titles as Caligari, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Der Golem. These films soon became part of the museum’s 35mm and 16mm circulating programs. With MOMA’s sanction as historically important classics, they remained the most widely accessible older films available to researchers and students alike for many decades.

There is, however, a second, largely separate audience: monster-movie fans. Starting in the 1950s, German Expressionist films were promoted as horror fare by Forrest J. Ackerman in his magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. In 1967 Carlos Clarens included Der Golem in his An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Really dedicated horror devotees pride themselves on their expertise across a wide variety of films, including foreign and silent ones. Der Golem became a certified horror classic.

In the 1950s and 1960s, companies offering public-domain 8mm and 16mm copies for sale enabled both film-studies departments and movie buffs to start their own film libraries. Ultimately home video made previously rare silent classics easily obtainable—including a restored Golem from the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung, with new tinting and a musical score, on DVD. Such a presentation reconfirms the film’s status as a classic.

But what sort of classic is it? An undying masterpiece that one must see immediately? A film one should definitely watch someday if the chance arises? On the occasion of Der Golem being presented on the big screen with live musical accompaniment, we have a chance to specify what distinguishes it from its fellow exemplars of Expressionism.

I suspect that horror-film fans won’t feel that a reevaluation is necessary. Der Golem is a forerunner of Frankenstein and hence an important early contribution to the genre. It’s a striking film to look at and obscure enough to impress one’s friends during a late-night program in the home theater.

But for film historians returning to Der Golem in the early twenty-first century, after nearly ninety years of taking it for granted, what is there to say?

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

It’s a subject susceptible to endless debate. To avoid that, it’s helpful to accept historian Jean Mitry’s simple, useful distinction between graphic expressionism, with flat, jagged sets, and plastic expressionism, with a more volumetric, architectural stylization. If Caligari introduced us to graphic Expressionism in 1920, Der Golem did the same for plastic Expressionism later that year.

For me, seeing Der Golem again doesn’t much affect its status as an historically important component of the German Expressionist movement. It’s not the most likeable or entertaining of the group. Caligari has more suspense and daring and black humor. Die Nibelungen has a stately blend of ornamental richness with a modernist austerity of overall composition, as well as a narrative that sinks gradually into nihilism in a peculiarly Weimarian way.

Moreover, Der Golem’s narrative has its problems. None of the characters is particularly sympathetic. Petty deceits and jealousies ultimately are what allow the Golem to run amok. The narrative momentum built up in the first half of  the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

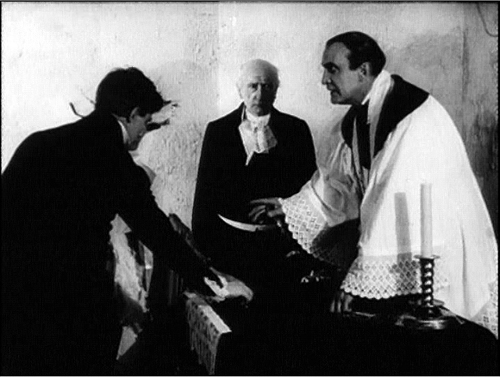

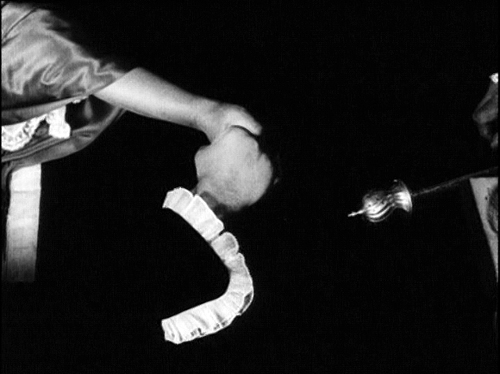

But putting aside Der Golem’s minor weaknesses, it has marvelous moments that summon up what cinematic Expressionism could be: the opening shot, which instantly signals the film’s style (below); the black, jagged hinges that meander crazily across the door of the room where Löw sculpts the Golem; the juxtaposition of the Golem with a Christian statue as he stomps across the crooked little bridge returning from the palace (at top).

Hans Poelzig was perhaps the greatest architect to design Expressionist film sets. He designed only three films, and Der  Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Speaking of performances: A lot of the actors in German Expressionist films were movie or stage stars who didn’t specialize in Expressionism. There were, however, occasional roles that preserve the techniques the great actors of the Expressionist theater. There’s Fritz Kortner in Hintertreppe and Schatten. There’s Ernst Deutsch, who acted in only two Expressionist films, as the protagonist in the stylistically radical Von morgens bis Mitternacht (out this month on DVD) and as the rabbi’s assistant in Der Golem.

Just watching his eyes and brows during his scenes in this film conveys something of the experimental edge that Expressionism had when it was fresh—before its films had become canonized classics.