Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

The Bologna beat goes on

Guy Borlée, Festival Coordinator for Cinema Ritrovato, in a pas de deux with Moira Shearer.

DB here:

Like most film festivals, Cinema Ritrovato is many festivals. There’s so much on offer you can carve out your own mini-fests. You may meet a friend for lunch and learn that you two have seen none of the same movies. So here are some titles from my sampled version of Ritrovato.

1909 and a little later

Le Trust (Feuillade, 1911).

As Kristin pointed out in our last entry, we spent a lot of time in the 100 Years Ago thread. Things were definitely changing on screens in 1909. True, you still had your costume picture with suspiciously insubstantial walls and props, your gimmicky special-effects comedies (e.g., The Electric Policeman), and your chase films with people falling over and getting up and running on, endlessly.

But you also had powerful movies like Capellani’s L’Assommoir, discussed by Kristin, and charming ones like Charles Kent’s Vitagraph Midsummer Night’s Dream. There were crime films like Tell Tale Blotter and An Attempt to Smash a Bank, with its peculiar slow reverse tracking shots linking the lobby and the banker’s office. There was Cowboy Millionaire, which presents the always-edifying spectacle of a buckaroo bringing his uncouth pals to the big city. There were wonderful Film d’Art items, not least Le Retour d’Ulysse, which had the most rapid editing pace of any 1909 film I clocked. There was even a lifelong romance told through the fate of two pairs of shoes (Roman d’une bottine et d’un escarpin).

Louis Feuillade was one of the finest directors of the 1910s, but most of his earlier work that I’ve seen doesn’t suggest his mature storytelling skills. Of the 1909 Feuillades on display in Bologna, the two I found most intriguing were La Possession de l’enfant, about a divorced wife who kidnaps and raises her child in poverty, and La Bouée, a touching tale about a fisherman’s family about to lose everything. But the cherry on the sundae for me was a pristine print of a 1911 Feuillade, part of Eric de Kuyper’s program of films about financial crises. My man Louis did not fail me.

In Le Trust, a businessman indulges in a bit of corporate espionage. He hires a detective (the sinister René Navarre) to kidnap an inventor and squeeze a secret formula out of him. The detective resorts to some unusual methods, such as hiring an actor to dress in drag and impersonate a rival’s wife. The inventor is kidnapped but outwits his captors with a trick that could have come straight out of Les Vampires. The plot’s outrageous surprises are played straight and brisk, and we can see Feuillade moving toward the compact, inventive staging of Fantomas and Tih-Minh. How could Le Trust not be my favorite movie of the week?

Tsars, Commissars, and Jews

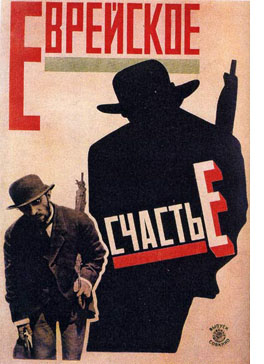

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Véra Tcheberiak (1917) is probably more important for its subject matter than its fairly simple technique. The two-reel film was the third to treat a famous case of anti-semitic hysteria under the Tsar. In 1913, a Jew named Beilis was charged with ritual murder of a Christian child, and it became Russia’s Dreyfus affair.

More elegantly directed was Evgenii Bauer’s worldly, somewhat cynical Leon Drey (1915) which retains its fascination. (I wrote about its staging in an earlier entry.) But its intertitles still need to be restored.

Two later films were strongly marked by Soviet montage influence. In The Five Brides (Piat Nevest, 1929-1930), a shtetl is threatened with a pogrom by a gang of bandits. The band will spare the citizens if five virgins can be offered to their leaders. Director Aleksandr Soloviev accentuates this dramatic situation with every trick in the montage playbook: fast cutting, low angles, handheld shots, dynamic graphic conflict, and even explosions and bursting waves as Red partisans ride to the rescue. The final moments are missing, but there is plenty to savor, including an emotionally complex scene in which the elders decide to sacrifice their five virgins and suffocate a young man who is trying to stop them. The film was revised for Russian release, but we saw the original Ukrainian version.

No less engaging, though a little more formulaic, was Remember Their Faces (Zapomnite ikh litsa, 1931). A young Jewish worker devises a machine to speed the work of a tannery, but his efforts are blocked by saboteurs and anti-Semites. In a slap to the New Economic Policy, the chief villain is a private entrepreneur who wants to make the tannery uncompetitive. The scenes in which Beitchik is casually bullied by young thugs are quite strong. The final moments, when the bullies won’t even let Beitchik leave town unmolested, present the stirring image of the Komsomol youths marching to rescue him. Such support did not materialize behind the scenes: the film encountered censorship at every stage and was given a modest release.

Despite a 1927 Party directive ordering films treating anti-Semitism as a threat to socialism, both The Five Brides and Remember Their Faces encountered obstacles at every turn, largely on the grounds that the Party was given too small or too passive a role. In a fine book accompanying the series, Valérie Pozner supplies details of how the films were censored and suppressed.

Capra, company man

Donald Sosin gives us Scott Joplin’s “Wall Street Rag” (1909), uncannily appropriate today.

One of the highlights of this year’s Ritrovato was the Capra series, featuring his surviving silent work and several early sound pictures. We were also lucky to have Joe McBride, professor, critic, and UW alum, there to introduce many sessions.

I didn’t attend the talkies, having seen the batch except Rain or Shine (1930), but several of the silents grabbed my attention. Most seemed to be attempts by Columbia to hitch a ride on the bigger studios’ successes.

The Way of the Strong (1928) is a post-Underworld exercise in hoodlum redemption, graced by vigorous action, swift cutting (4.3 sec ASL by my count), and nice juggling of recurring props (mirrors, pistol barrels, a book devoted to great lovers). And the plug-ugly hero is truly ugly, none of your Hollywood fake-ugliness; a face only a blind girl could love. Submarine (1929) is a take on the What Price Glory plots analyzed by Lea Jacobs in her recent book. Two amiable sides of beef brawl and drink their way through navy life until a woman comes between them. The sexual rivalry is compelling, and the suspense during a stifling undersea rescue is admirably sustained. The Younger Generation (1929) owes something to the back-to-your-roots impulse of The Jazz Singer. Based on a Fannie Hurst story, it tells of a Jewish family that rises into society because of the son’s business acumen; in the process, class snobbery makes them increasingly unhappy.

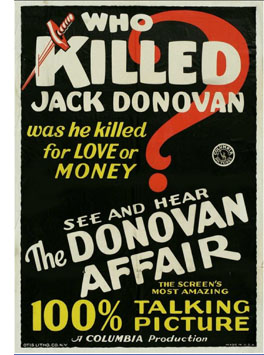

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

The movie was made in both silent and sound versions. Our print was silent, but it had no intertitles. At first blush it seemed to be the sound version without its track, sort of a 000% talking picture. The print’s average shot length is 9.3 seconds—too long for most late silents, but typical of some early talkies. Yet this did not look like any 1929 American talkie I have seen.

It had silent-film lighting, some huge lip-sync close-ups, and very smooth cutting. Except for a couple of moments, it lacked the jerky reframings, the long-lens imagery, and multiple-camera coverage typical of shooting from booths, the common practice of early talkies (and the talking sequences of The Younger Generation). Capra’s setups sat well inside the action, as was the case in 1920s silents and as would be the case in single-camera sound films a few years later.

Crazy as it sounds, I had to wonder if we were seeing a copy of the silent version made before titles were inserted! This is very unlikely. But if this was indeed an early talkie version, Capra was able to shoot sound with a fluidity that directors at bigger firms didn’t display—and in a rented studio at that, if the AFI Catalogue is to be believed. On the road and away from my research base, I can’t investigate further, but if you know more about the Donovan Affair affair, feel free to correspond and I’ll add postscripts.

Whatever the provenance of that Library of Congress print, the other silent/ early sound Capras have been admirably buffed by Sony’s Grover Crisp and Rita Belda (another Wisconsinite). The prints’ sparkle and sheen prove that even a minor-league studio (which Columbia was then) could turn out gorgeous imagery, thanks in no small part to cinematographers like Joseph Walker and Ted Tetzlaff.

Miscellany

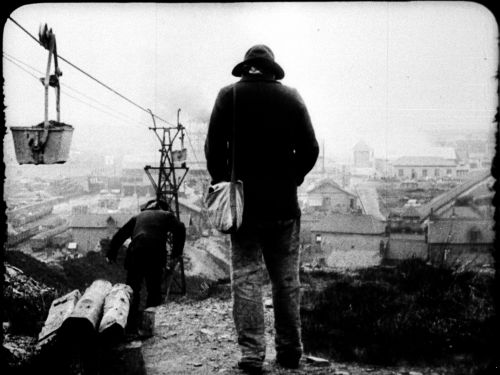

The Lewinsky Dog surveys the climactic battle in Karadjordje (1911).

Be Patient! Department: Anke Wilkening, who was among those announcing the discovery of a new Metropolis print last year, gave us an update on the restoration process. The archivists are nearly done integrating the Argentine footage into the whole. Next comes the cleanup phase—awkward because the original Argentine print was heavily scratched and what we have is a 16mm copy and cropped for sound at that.

So far, the restored footage is clearly making secondary characters like Josaphat and the “Thin One” more prominent. But even the Argentine print is lacking things known to us, as three clips illustrated. Getting everything in some order will take time. Anke promises another report next year.

Box sets routinely attract attention at Bologna’s annual DVD awards, and this year things went according to form. The top prize went to Joris Ivens, Wereldcineast, a vast assembly of rare work by the Dutch filmmaker. Another generous package, Flicker Alley’s Douglas Fairbanks set, won best silent-film box set. (We have an entry on it.) Two more big collections, GPO Film Unit Collection vol. 2 (BFI) and Treasures from American Archives IV (Film Foundation) triumphed in the Sound Film and Avant-Garde categories.

Other winners: the two Vampyr releases (Eureka and Criterion) and Berlin, Symphony of a Big City (Munich Filmmuseum) for their rich bonus materials; Vittorio De Seta’s documentary collection Il Mondo Perduto (Feltrinelli Real) and two studies of Pasolini’s La Rabbia (Raro) in the Rediscovery category. Cinema Ritrovato wisely acknowledges that DVD producers are contributing powerfully to research into film history and are making rarities available to viewers who live far from festivals, archives, and cinematheques.

Not heralded—in fact, just sitting on the counter at the ticket booth—were still other DVDs, this time from Serbia. Sharp-eyed Olaf Müller pointed them out to me, and I’m grateful he did. Two volumes from the “Film Pioneers” series include a set of newsreels and, happily, the 1943 Innocence Unprotected (which Makavejev “decorated” in his revised version of 1968). A third disc consists of Karadjordje; or, Life and Deeds of the Immortal Duke Karadjordie (1911). This is the first Serbian and Balkan feature, and is thus, as the box text indicates, “one of a kind.” Same goes for Cinema Ritrovato itself.

Gian Luca Farinelli and Peter von Bagh, two more we have to thank for a great festival.

Just in time for Bologna, the historical journal 1895 has published a splendid special number on Le Film d’Art, ed. Alain Carou and Béatrice le Pastre. Feuillade’s Le Trust is available on the Gaumont early years DVD set and will soon be released on a Kino set drawn generously from the Gaumont collection. Keep your eyes open for early Capra features on Turner Classic Movies; several have run there recently.

Back in Bologna

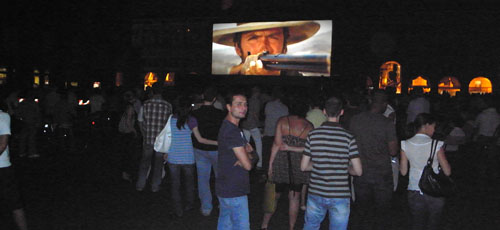

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

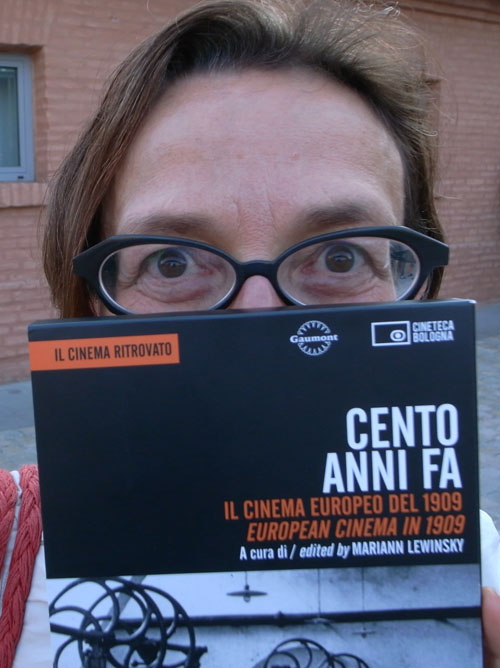

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.

Cinema in the world’s happiest place

Bust of Carl Theodor Dreyer in the Dagmar Bio, the film theatre he once managed.

DB here:

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited. Having never been to Canada or Mexico, I took off in the early summer of 1970. Technically, I touched down in Reykjavik first because I was flying Icelandic Airlines, the Ryanair of its day. You flew Icelandic to get to Europe as cheaply as possible. Although a few people got off at Reykjavik, most of us sat patiently on the tarmac before heading off to Copenhagen.

Ever since that summer, when blinding light invaded my basement room at 4:00 AM, I’ve had a soft spot for Denmark. Ib Monty, then head of the Danish Film Archive, kindly screened for me all the Dreyers I hadn’t seen, and in spare moments I learned the joys of Copenhagen’s canals and restaurants. Six years later I would spend nearly another whole summer there watching the same Dreyer films on a flatbed viewer in the archive vaults, a somewhat renovated army fort. Many visits later, including a couple to the charming city of Aarhus, I’m still a fan of the Danes. They manage to be modest yet accomplished, hard-working yet hard-partying. They put cultural figures like composer Carl Nielsen on their currency. We’re told that they are the happiest people in the world. I don’t doubt it.

So it was with special pleasure that I returned to Copenhagen for two weeks in June. The second week was consumed by a day of talks and seminars at the University of Copenhagen and then by the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I’ve given two long-winded previews of the latter event, and I hope to have more coverage of it in a later entry. Today, a smorgasbord of other things Danish–without, alas, mention of H. C. Andersen, Vilhelm Hammershøi, or Victor Borge.

Chaos reigns, more or less

The organizers of our SCSMI event pulled off a coup: Not only were we shown Antichrist in Asta, one of the Danish Film Institute‘s fine theatres, but along came Lars von Trier to spend an hour talking about it afterward.

The film struck me as mid-level von Trier, not as good as The Idiots, The Kingdom, Dancer in the Dark, and The Boss of It All (though others would call me out for admiring this last). It lacks the element of game-playing that I enjoy in what von Trier calls his “mathematical” works, most famously The Five Obstructions. Instead, Antichrist provides perhaps the most unadulterated surge of emotion and mystical/ mythical implication to be found in all his work. It tries to be an intellectual horror film somewhat in the David Lynch mode, with a plaintive, roiling soundtrack and unearthly visions, including a fox snarling, “Chaos reigns!”

I was surprised that the elements so sensationalized by the press are pretty brief; snip out four brief shots and you’d have a ferocious but much less controversial movie. It starts as your basic two-handed psychodrama, with a couple tearing at each other. As in those other duologues Strindberg’s The Stronger and Bergman’s Persona, the film presents a fluctuating power struggle–the man trying to rule through cool rationality, the woman tapping depths of grief and repressed anger.

Yet the film goes beyond psychodrama into realms of history and myth. The grieving mother rises into demonic fury by getting in touch with witchcraft, the subject of her unfinished university thesis. Antichrist could thus be read as an exercise in misogyny or as a celebration of woman’s primal energies. (For what it’s worth, several women in our audience said they liked the film a lot.) Of course the whole thing looks very fine, with a stylized black-and-white prologue (some shots taken at 1000 frames per second), and the rest rendered in that dodging, wandering camera style von Trier and the brilliant cinematographer Antony Dod Mantle have made their own.

The entire Q & A with von Trier, moderated by Peter Schepelern, is available as an audio file on the SCSMI conference website, perhaps to be followed by a video record. Some excerpts:

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

The Antichrist project seems to have brought out a mystical side of von Trier that hasn’t been so prominent in his public image. Years ago he conceived a film in which Satan created the earth, but that dissolved. Certain elements of the film, especially the emblematic forest creatures–blackbird, deer, and fox–come from his interest in shamanism. He has, he claims, traveled in alternative worlds with animal guides. “Never trust the first fox you meet.”

Is it a horror film? At least it has sources in the genre. Uncharacteristically, von Trier prepared for the project by revisiting not only classic horror films he admired, The Exorcist, The Shining, and Carrie, but also The Ring and Dark Water. He was particularly influenced in his youth by Altered States, another venture into “fantasy travels.”

He commented on how his free-camera technique imposed certain constraints in sound work. If you execute a “time cut”–that is, cutting directly to a new scene starting on a shot of a character–you must alter the sound somehow; otherwise the audience is likely to think that the action is continuous. This got me thinking about how The Boss of It All violated that convention, when each continuity cut actually yields a different sound ambience because each of the many cameras is miked separately.

Why is the film dedicated to Tarkovsky? “It was a way of getting rid of psychology.”

“I do not work with the audience in mind. I make films I would like to see myself.”

The Last is not least

Last Friday night the filmmaking program at the University of Copenhagen gave out its student film awards. The crowd was large and boisterous, the atmosphere festive and tipsy. I was honored to present the prize for the best fiction film, which went to desidst (punning on De sidst, “The Last”). The three winning filmmakers, pictured above, were Sissel Marie tonn-Petersen, Niels Holst-Jensen, and Toke Westmark Steensen.

Before I read the result, though, I was confronted with some damaging evidence in a copy of Film History: An Introduction.

Peaking in the 1910s

During my first week in Copenhagen, I was viewing Danish films from 1911 to 1915. As long-time readers of this blog know, I’m fascinated by the films of the 1910s, and Denmark boasts some of the most sophisticated works of the time. Thomas Christensen and Mikael Brae of the Danish Film Archive kindly let me watch several films, mostly from the once-mighty Nordisk film company.

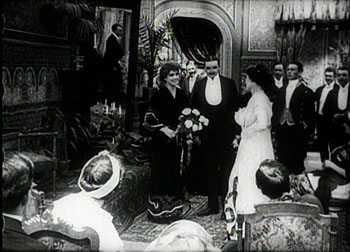

The most remarkable films I saw were Ekspeditricen (1911), Dyrekøbt Aere (“Hard-Won Honor,” 1911), and Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (“Under the Beam of the Lighthouse,” 1913). All three of these offer sophisticated examples of the dominant storytelling technique of that period, what has been called the tableau style.

I can’t offer any visual analyses here, as I don’t have frame stills available in digital form, but here’s an example of the kind of thing I’m studying, taken from August Blom’s The Ballet Dancer (1911). Camilla (Asta Nielsen) has been seduced by Jean, a man-about-town, and she has come to sing for a society soirée at which Jean is present. But Jean is also carrying on an affair with the host’s wife.

The scene starts with the host Simon walking with his wife to the middle of the salon. Note the mirror in the upper area of the frame, just left of center.

She goes out frame right, and the host welcomes Camilla, bringing her to the central zone of the shot.

The hostess returns from off right to greet Camilla. Now we can see Camilla’s lover Jean in the mirror.

The hostess leaves the frame again, her husband settles into a chair, and Camilla starts to sing. But in the mirror we can see Jean bending over to kiss the hostess.

Soon Camilla notices Jean’s flirtation, and he straightens up.

Camilla interrupts her song, shouting and thrusting an accusing finger at the couple across the room.

I especially like the way in which Camilla’s finger points both at the offscreen couple and directly at her guilty lover’s reflection. If we haven’t noticed Jean’s infidelity yet, we certainly should now.

Today the same scene would be handled with lots of cutting and point-of-view framings, but the mirror allows Blom to pack a single long shot with simultaneous actions. (Mirrors were something of a signature device in Danish films of the period.) It’s a nice example of Charles Barr’s notion of gradation of emphasis, a principle that was at the heart of the intricate, sometimes exquisite ensemble staging we find so often in the 1910s.

Far from being a static, “theatrical” rendering of the action, the tableau technique looks forward to the deep-space stagings we associate with Welles and Wyler, as well as the distant long-take style of Theo Angelopoulos and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Studying film history is often our best way to understand the cinema of our moment, and perhaps of our future. At a more primal level, a week of prime examples of the tableau tradition gave me a fine dose of Danish happiness.

For background on the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference this year, try here and here. Earlier blog entries on this site have dealt with other aspects of 1910s cinema: director Yevgenii Bauer, tight staging in De Mille’s Kindling (1915), the emergence of classical film style around 1917, editing in William S. Hart movies, the years 1913 and 1918, and the triumph of Doug Fairbanks. I’ve proposed more complete accounts of 1910s staging strategies, and their impact on film history, in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

An excellent introduction to Danish cinema of this period is Ron Mottram’s 1988 Danish Cinema before Dreyer, a book which deserves to be reissued or put online. You can sample Danish 1910s films at the DFI archive database, where several clips are posted. Try these fragments: København ved nat (1910), Den frelsende Film (1916), and Kaerlighedsvalsen (1920). DVD versions of some 1910s classics, including The Ballet Dancer, can be ordered from the DFI Cinemateket shop; in the US, the titles are available for institutional purchase from Gartenberg Media. Everyone interested in silent cinema should own the Dreyer, Christensen, Psilander, and Asta Nielsen discs.

Acting up

Germinal (1913).

DB here:

Film performance is notoriously difficult to analyze. We don’t lack zesty celebrations of actors; I think especially of Richard Schickel on Doug Fairbanks and Gary Giddins on Jack Benny and Bob Hope (praised in an earlier entry). But we have long found it difficult to penetrate actors’ secrets with the same precision that we bring to editing or framing or a film’s musical score.

Actors’ performances don’t offer themselves in neat slices, the way that shots come to us. There isn’t a firm notational system that lets us capture performances the way that scores can pick out important patterns in music.

Moreover, it’s hard to dissect something that seems so evanescent, so direct, and so natural. When we see someone smile on the bus or at a party, we react immediately and without any apparent thought. When someone smiles in a movie, we’re tempted to say that we respond just as directly. But then, what is acting? Just doing what comes naturally?

Acting is clearly an art and a craft. Not everyone can do it, and comparatively few do it well. So if there is a skill or a technique involved, surely acting goes beyond ordinary behavior. And if as in other arts there are creative choices involved, there is likely to be a menu of options to be chosen from. Some of those options are likely to be conventions sanctioned by tradition. How strongly, then, is acting conventionalized? If it’s conventionalized to some degree, we should be able to analyze it.

A small-scale debate has gone on for some years in film studies about whether film acting is heavily conventionalized, even coded. Advocates of the coding view point to the fact that acting styles vary in different places and change across time. What does Kabuki performance have in common with Method acting? It’s hard to claim that there is a universally realistic acting style that naturally represents human behavior. Against this, others have argued that even if there is no absolute and unchanging standard of realism, we can speak of more or less realistic aspects of performance. Some styles, like Method are just less artificial than others, like Kabuki—even if both are somewhat stylized with respect to realistic behavior.

My own view, explored in Poetics of Cinema, is that performance traditions streamline or stylize a common core of widely shared human behaviors. In everyday life, smiling expresses happiness and/or serves as a social signal of openness. We’re unlikely to find a distant culture in which smiling expresses rage. (Of course we can have an instance of smiling concealing rage, but that would acknowledge the difference between the two states.) Some acting traditions, like Kabuki, retain certain common behaviors like weeping or proud walking, but make them more dancelike. Other acting traditions stylize core behaviors in different ways–the mumble of the Method, or the comic double-take. The differences lie in what aspects of facial expressions, gestures, gait, and the like are on the tradition’s menu, and how they become “streamlined” for expressive purposes and spectatorial uptake.

In short, I’m a moderate constructivist about such matters. I agree that we have to learn to comprehend performances in different traditions. But our learning is fast and spontaneous, not at all like learning Morse code or English, because we already have strong hunches about what a frown or a wail might express. Frowning or wailing are likely to be contingent universals of human behavior. An intuition about the meaning of the performance guides us to recognize the more stylized aspects of the presentation. When Cesare coasts along walls in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, we take that to be a stylized representation of the act of stalking. That construal relies on the hunch that he’s doing something we already understand–stalking–in an unusual way. Although sometimes we might have to revise our intuitions about the meaning, those intuitions serve as a point of departure. (Where do our intuitions ultimately come from? Short answer: The evolution of humans as a social species.) E. H. Gombrich put it well: “It is the meaning which leads us to the convention and not the convention which leads us to the meaning.”

Assunta Spina (1915).

The faculty and alumni of the Film Studies program here at Wisconsin keep in touch through a (closed) listserv, and thanks to Jonathan Frome we also have a wiki, to be found here. It’s just starting to fill up, mostly with ideas for teaching and examples of sample sequences to illustrate film techniques. But now the wiki has gained striking essays on acting from two scholars of early cinema.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book, Theatre to Cinema, took on the problem of what early feature films owed to the stage, and they concluded: Quite a lot. But instead of condemning this tradition as “uncinematic,” as most historians have, they showed that a highly engaging form of cinema arose by reshaping theatrical traditions. Specifically, Ben and Lea examined how “situational” plotting principles were carried into film, and they discussed film’s debt to the “pictorialist” drama of the nineteenth century. Many scholars had argued that melodramatic theatre was replaced by the Naturalist theatre, derived from the literary movement associated with Émile Zola. But Lea and Ben argued that a pictorialist conception of theatre and its modified form in early feature films cut across this distinction. A film that was avowedly Naturalist in plot or theme could maintain conventions of earlier forms.

Consequently, they argued that film acting of the period, even when it seemed to be moving toward greater realism, was still building on the stereotyped expressions, gestures, and attitudes of pictorialist theatre. Actors were called upon to execute vivid stage tableaus. Standard gestures had to be imbued with fresh emotional intensity, and actors were expected to move gracefully from one expressive picture to another.

Now Ben and Lea have extended their book’s argument in two in-depth studies posted on the UW wiki. Ben’s essay examines that great Capellani film Germinal (1913) and shows that it often perpetuates the poses and expressions of pictorialism, while also scaling them down. Lea tackles the work of the diva Francesca Bertini, including an analysis of the wonderful Assunta Spina (1915). Her piece is a companion to Ben’s. She writes:

While I do not doubt that the plot of Assunta Spina fits under the rubric of naturalism, and that the acting and staging of some scenes in the film also show the influence of naturalism in the theatre, it seems to me that Bertini’s technique (and incidentally that of [Asta] Nielsen as well) is more reminiscent of Bernhardt than it is of the Duse, and that the blocking and use of gesture in the film is largely governed by what Brewster and I have discussed in terms of “pictorialism” in acting.

By considering 1910s performance as a modification of theatrical poses, attitudes, and staging conventions, Jacobs and Brewster are led to remarkably detailed analyses. They have studied the conventions of acting at that period, and because they are alert to standard bits of business, so they are able to show fine points of performance that we would ordinarily miss.

They’re also able to hold the realism/ artifice dispute in suspension by concentrating on particular historical traditions. They shrewdly note that as acting styles change, the newer one is likely to be praised as more realistic than the styles it supplants. In turn, that style will be considered artificial when a still newer one comes along. For this reason, Method acting may seem less realistic and more artfully contrived today than it did in the 1950s.

Apart from the subtle discussion of acting styles, one merit of these essays is that they recognize how films can take bits and pieces of different traditions and modify them for particular ends. I’m sympathetic to this perspective. For instance, I still think that many of today’s Hollywood films, despite their contemporary look and feel, draw on principles of narration and plot structure that we can find in classic American studio cinema.

In addition, you ought to visit the site to see how detailed their analyses are and how extensively they draw on frame stills. Indeed, one reason they published these pieces online was that no academic film journal could have accommodated so many illustrations. So much the better for us. The frames, taken from 35mm prints with a Nikon lens and negative film, are among the most beautiful you’ll find on the Internets. I swiped some here.

Sangue bleu (1914).

The quotation from E. H. Gombrich comes from his essay “Image and Code: Scope and Limits of Conventionalism in Pictorial Representation,” in The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), 289.

Kristin has written a couple of blog entries concentrating on performance, here and here.